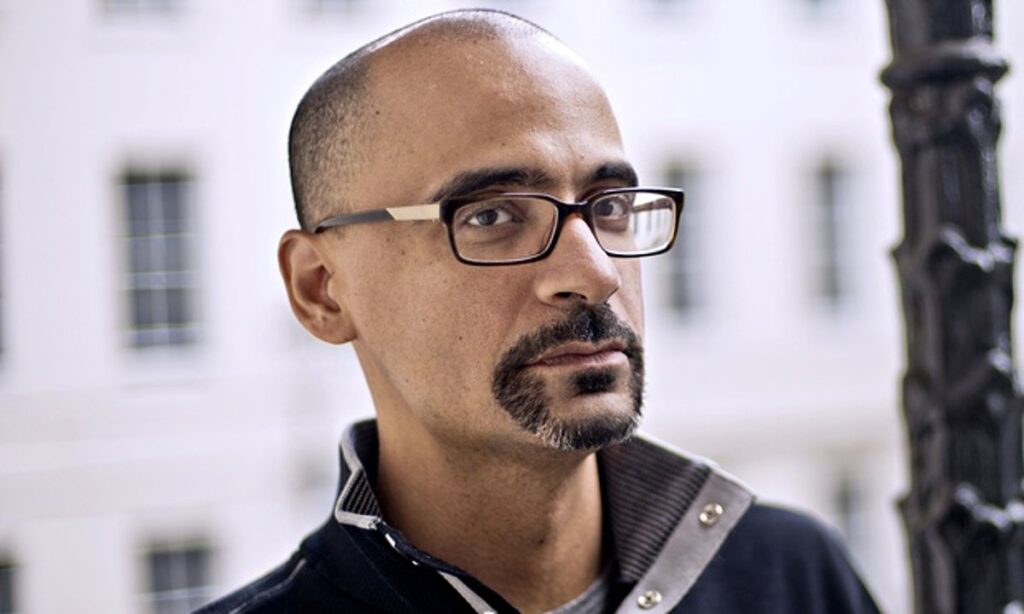

In the inaugural episode of BR: A Political and Literary Podcast, Junot Díaz talks to Avni Majithia-Sejpal about dystopian imaginaries, critical futures, and the rice and beans of literature. Throughout 2017, Boston Review will feature stories, essays, and interviews on the theme of global dystopias. The project will culminate in a special print issue in the fall of 2017, edited by Junot Díaz. More information and submission guidelines can be found here.

Don't miss an episode, subscribe to BR: A Political and Literary Podcast on Soundcloud or ITunes!

Avni Majithia-Sejpal: You are editing a special literary issue of Boston Review, to be published in 2017, on global dystopias. Can you tell us about your vision for this issue: why dystopia, and why now?

Junot Díaz: Certainly we are at peak dystopia. We are in a moment where there is, first of all, the creative problem that there is a lot of praxis around dystopia. It has become, along with apocalyptic narrative, the default narrative of the generation. Our political horizons have become distorted by dystopian imaginaries. Our sense of what is possible in the civic is being slowly dragged away from the standard post-World War Two techno-positivism towards a darker, more ruinous vision. It is not only a kind of vocabulary and idiom; it is a useful arena in which to begin to think about who we are becoming as a planet. The steady drum beat of reports from our best and brightest scientists has made it explicitly clear that whether we like or whether we want to admit it or not we have damaged our planet in ways that have transformed us into a dystopian topos. When I think of it in The Hunger Games where, either the movie or the book, a group of people come together and design arenas where people—young people—kill themselves and compete: these are the game makers. We are making the genre in which we are living, and we are making it at such an extraordinary rate.

We are at peak dystopia. Our political horizons have become distorted by dystopian imaginaries.

There are also questions of politics, questions of subjectivity, questions of responsibility in the civic that dystopia brings out. We have a great tradition of dystopia in the West as a way for us to imagine our way through our present and to indicate towards the future. I have always enjoyed Tom Moyland's idea of the critical dystopia: the purpose of the critical dystopia, how the critical dystopia is implicated with the utopia, and that a critical dystopia is not just something that is "the bad place." It is something that maps, warns, and hopes. In that way—as an arena of intellectual engagement—the critical dystopia taken to a lower level could be something regenerative and something useful. And that's what we would like to see from this special issue.

AMS: The other part of the special issue is the term "global." How do you envision the global and what are its parameters?

JD: As soon as you evoke the global you immediately recognize your failure: it is a gesture that immediately produces failure. And yet one must attempt to engage as many modalities, as many geographies, as many identity matrices, as many people, so as to provide epistemic privilege and epistemic insight. There is nothing more utopian than hoping that with an already ruined, small, defective attempt to put your arms around this multitude you could possibly achieve it. It is as much a design ethos as it is a proclamation of faith.

AMS: What are the stakes of dystopian literature, particularly in contrast to what we think of as literary fiction?

JD: I'm not sure that one can safely sift these traditions out, that one can put literary fiction on one side and the dystopic or the critical dystopic on the other. One has to understand that all of these have been in conversation with each other for a long time. What is fascinating about dystopian literature, dystopian narrative, the dystopian mode, is that it is already engaged with a very useful narrative tradition. It summons people into a room who might otherwise not be there, so that we’re going to get 1984, we’re going to get We, we're going to get The Handmaid's Tale, we're going to get The Hunger Games, and onward and onward and onward. We are going to have texts, writers, and thinkers, that aren't always explicitly in a conversation, and that is not a bad starting point. There are worse sets of texts to have in a room for conversation than some of our more classic and better-known dystopias. You cannot think of dystopian literature without thinking about Octavia Butler. On the other hand, it might be easy to allude to Octavia Butler if you’re having a larger conversation about literature. I find it reassuring to think that Margaret Atwood and Octavia Butler might not be far apart while we are having this dialogue.

As soon as you invoke the global, you immediately recognize your failure. And yet one must attempt to engage as many modalities, as many geographies, as many people as possible.

AMS: In an essay published in the The New Yorker titled “MFA vs. POC” you talk about the cultural whiteness of MFA programs. You write: "Race was the unfortunate condition of nonwhite people that, as such, was not a natural part of the Universal of Literature, and anyone that tried to introduce racial consciousness to the Great (White) Universal of Literature would be seen as politicizing the Pure Art." Is there a particular valiance to genre fiction for minority writers both within the US and globally?

JD: I just think, we're needed everywhere. For example, if I was interested in genre, which I am, I could create an argument around the special privileges and dispensations and what it can really do. And certainly there I have done that, and these are very true. But I would argue that anywhere where we are not present in the numbers that we should be present in, there are very useful things for us to do. There are very useful contributions, and our contributions are being marginalized. It is not as if we didn’t have Asian American, or we didn’t have Indigenous writers in the speculative genres. But that of those of us who are present, there is not enough of a critical mass to push back on the forces that are trying to erase, minimalize, and marginalize us. We don't just need our presence there because we are good to think, because what we contribute is important to the philosophical, to the literary, and all that has to do with what is human. We also need ourselves there because we need to be able to protect ourselves against very hostile ideological forces that have a lot at stake to guarantee that our voices and criticisms are marginalized. Then, when we think about the dystopian, when we think about science-fiction, we are often thinking about speculation and the politics of the future. For a very long time women, people of color, women of color, have been excluded from the dialogues of the future, from the politics of the future. This is of extraordinary importance, because what we bring—our critique of the present, our understanding of the present—is absolutely essential to produce a future. Our lack of presence in these areas, or our small numbers in these areas, problematically guarantee that in the future the toxic present may continue itself. We have got to chase these regimes everywhere they go, whether they imagine and re-imagine and re-create themselves in a past, whether they imagine, re-imagine, or re-create themselves in a fantastic other-space, or whether they are attempting to colonize the future. We need to go there and defend humanity, defend our humanity.

Our critique of the present is absolutely essential to produce a future.

AMS: And speaking of marginalization, I also wanted to ask you about Afrofuturism. Much has been made recently about Afrofuturism as this great big tent under which African writers, African diasporic writers, and African-American writers are sometimes placed. That capaciousness can either be seen as a good thing, or as a way to bracket non-white writers. Do you find it to be a useful term?

JD: African diaspora is an umbrella term that I don't think is as precise as folks would like it to be. But that is the nature of attempting to address what we would call multitudes of multitudes. I agree with Alondra Nelson: I think that this is a very beautiful set of analytics, I think that it is a very useful set of ways of engaging an aesthetic reality, it is a way to begin engaging places the African Diaspora has rarely ever been immediately associated with. I don't mind how Afrofuturism is still something in the making. I feel that Afrofuturism is sort of in the place where hip hop was when I was listening to hip hop as a young person: no one knew precisely what the hell it was. And it hadn't solidified or ossified into this instantly recognizable, instantly definable set of conditions and terms. I relish that moment of becoming, because let me tell you, I've lived both sides of it and I'm not sure that the discreet, compact, livable, easy–to-describe has a lot to recommend itself for.

AMS: What are some of your favorite literary dystopias?

JD: Well, I love Herland, of course. I swear by The Handmaid's Tale, and I swear by Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower. Her book Dawn, also, is sort of in the tradition, but because it is so science-fiction-y people often don't see how dystopic it is. And the standards of classics: Zamyatin’s We, 1984, Brave New World, A Clockwork Orange—both the novel and the film—very rapey and very disturbing in that way. And there are texts that have dystopias in them: Richard Adam’s Watership Down. Inside of Watership Down there is a really disturbing dystopia. It is important to look for where dystopias appear not simply in the larger sense of the genre of the entire text, but where they find themselves in other kinds of genres and other kinds of texts. And, of course, you could go right into Bladerunner; it can go on and on and on. I'm a huge fan.

Don't miss an episode, subscribe to BR: A Political and Literary Podcast on Soundcloud or ITunes!