Gob's Grief

Chris Adrian

Broadway Books, $24.95 (cloth)

Starting with Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage and picking up momentum through Faulkner, American writers of historical fiction have all but strip-mined the Civil War for literary ore. The last few years have seen a new proliferation, with Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain, Frederick Busch's The Night Inspector, Russell Banks'sCloudsplitter, Stewart O'Nan's A Prayer for the Dying, and Michael Shaara's Killer Angels leading a phalanx of novels set against the backdrop of the American Iliad.

Even in this crowded field, however, Gob's Grief is something new. Chris Adrian's ambitious first novel is no less than a magical realist work of historical fiction. This combination is not, in itself, an innovation; much of Toni Morrison's and Gabriel Garcia Marquez's work is historical in nature. But what does stand out in Adrian's novel is the way he combines verisimilitude with implausibility. It is hard to think of another author who would make Walt Whitman one of the protagonists of a novel, painstakingly modeling much of his dialogue on Whitman's own letters and prose writings and vividly reconstructing the post-bellum New York City that Whitman knew, and then have the poet interact with Pickie Beecher, a boy brought to life by a machine out of an aborted fetus. (Not only that, Pickie turns out to be the unborn child of the infamous affair between Henry Ward Beecher and Elizabeth Tilton.)

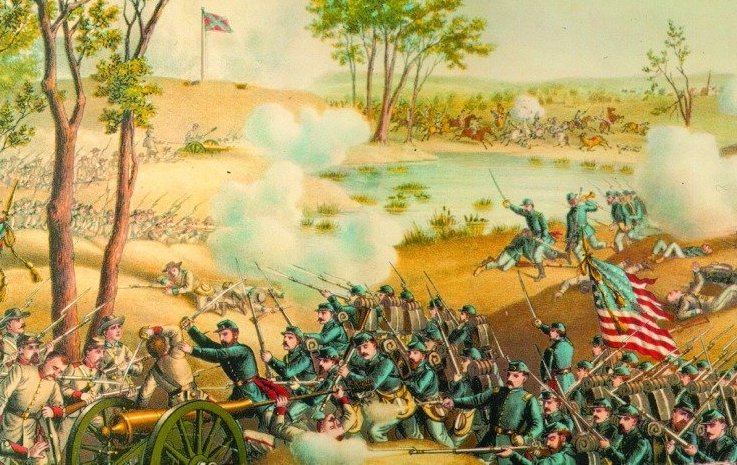

While much of the action takes place in the years after the Civil War, the story begins during, and remains rooted in, the conflict itself. The novel opens with eleven-year-old Tomo Woodhull running away from home to fight for the Union while, at the last moment, his twin brother Gob balks and stays home. In the span of a dozen or so pages, Tomo is adopted by an all-German Ohio regiment, proves himself a talented bugler and ruthless soldier, and dies at Chickamauga.

This short prefatory chapter contains some of the novel's strongest writing. Adrian uses Tomo's puerile sensibility to good advantage, and the war through the boy's eyes is equal parts nightmare and game. Here is the death of Aaron Stanz, the kind soldier who briefly serves as Tomo's surrogate father:

The artillery spent itself as Aaron Stanz ran, and did not touch him, but then he came under furious, withering rifle fire, and seemed to disappear before Tomo's eyes. Little pieces of Aaron Stanz—a finger, a portion of his hat, part of his nose—were suddenly not there, and then he proceeded to disintegrate as butterfly-sized pieces of flesh and bone flew away from him. He ran to within a few yards of Tomo before there was not sufficient body left for his will to propel.

Tomo is feverish with an infection, which amplifies the hallucinatory imagery around him, lending a touch of whimsy that makes it all the more horrifying. Adrian perfectly captures this surreality: the image of a man dissipating into a bloody cloud of butterflies at once subtly suggests an Ovidian metamorphosis and renders immediate an all-too-real event.

After Tomo's death, the story is taken over in turns by the story's four protagonists, and, whereas earlier Adrian worked in the thin air at the edge of reality, now he plants his flag firmly in the surface of the fantastical. Each of the main characters is left bereft and haunted—literally—by the Civil War. Whitman hears his own poetry (poems that he has written and that he will yet write) quoted back to him by the voice of dead Hank Smith, a boy with whom he fell in love while tending to the wounded in a Union hospital. It is this voice that urges Walt to befriend Gob, whom he quickly comes to think of as his new "camerado." Will Fie, Gob's friend and assistant, after losing both a brother and his only friend to the war, is tailed by a pack of ghosts and an ominous angel. Maci Trufant, destined to be Gob's betrothed, writes letters to her brother in the Zouaves, then finds that her left hand, unbidden, writes his replies after he is killed. And then there is Gob, whose grief drives him to apprentice himself to the Urfeist, a demonic figure with magical powers, to learn how to bring back his brother. One by one, we follow the other characters as they are drawn into Gob's endeavor, his increasingly monomaniacal quest to build a machine that will bring back all of the dead.

Discussing Toni Morrison, the critic James Wood once argued that magical realism, by forcing us to discard our notions of the real, often "corrupts our ability to judge fiction, which is a measured unreality." All too easily, such fiction can lapse into an unmeasured unreality, "the magic kingdom of fairy tale, in which happenings have an unexplained extremism that seals them from rational inspection." Adrian and Morrison share an earnestness that differentiates them from Salman Rushdie and even Gabriel García Márquez. The latter throw their artificially unruly worlds into sharp relief by interjecting professions of wonder and bemusement. That wink, that recurring reminder that this is, indeed, strange, allows implausible fictions to serve as commentaries on their own genesis, to remain, in a sense, "measured."

But Adrian, unlike Morrison, does not demand that we accept his creations simply on the strength of authorial authority. On the contrary, having discarded the rules that normally separate the plausible from the implausible, he is all too eager to expose the logic behind his alternate universe. Will's ghosts, for example, are no great mystery, since while serving in the war he becomes fixated by the photographic negatives—which look to him like "portraits of ghosts"—that he helps develop for Frenchy, a war photographer who happens to be obsessively trying to capture the precise moment when the spirit leaves the dead body. Maci's "ghost-written" letters obey a similar reasoning: in life her brother sends her stories and drawings of his life at the front, afterward her hand writes out news of his life after death and drawings for Gob's machine. This Newtonian symmetry is relentlessly applied, and every instance of "the unexplained" arrives with its metaphorical explanation tied on like a luggage tag.

The point here is not that the meaning of strange events should invariably remain obscure. It's just that the characters themselves are flattened by this implacably literal-minded manipulation. One can well understand the frustration of the Urfeist, who, upon receiving a message that reads "You are dead" from the "spiritual telegraph" young Gob has built (a precursor to his anti-death machine), storms out of the room only to die shortly thereafter. Indeed, like spawning salmon, Adrian's characters seem inevitably to die when they reach their moment of fulfillment. There's Frenchy, who finally does get his morbid money shot only to be killed at the same instant; Maci's brother Rob, whose letter completing a composite portrait he has been sending her is the last she receives from him; and even, finally, Gob.

The novel becomes a sort of Skinner box, the characters within prodded and cajoled by jolts of the otherworldly. Even Whitman's verse is partially reduced to a stimulus-response pattern through Hank, who, as both muse and incarnation of grief, does some of Whitman's work for him. In turn, the reader, too, becomes a victim of this deterministic equation. By pre-emptively catering to our skepticism, Adrian leaves no room for the ambiguity and complexity that, more than a strict adherence to the demands of rational explanation, make the world of the novel truly real.

The metaphorical weight that drives this clockwork universe is Gob's grief and the great machine that grows out of it. Five stories tall, built of cogs and cable and bone and batteries and even a pair of wings made of Frenchy's photographic memento mori, it is, like the novel itself, wildly implausible but built on a nonetheless stern logic. How could Adrian not see Gob's and his own endeavors as of a piece? Is this, then, Adrian's wink? After all, Adrian does make Gob the son of Victoria Woodhull, the flamboyantly iconoclastic nineteenth-century radical, who enlisted the help of her "spirit guide" Demosthenes in her fight for women's suffrage and sexual emancipation. In Adrian's world, however, Gob's mother, despite her past as a humbugger, nonetheless possesses unsettling, mysterious powers. The machine itself, the great white whale at the center of the novel, is not merely a symbol of loss and striving and the utopian impulse of the age but an actual device to abolish death.

Indeed, the novel's climax shows Adrian at his most grimly algebraic. The reader witnesses the moment when the machine swings into action through Maci, who, up until that moment, has managed to remain resolutely skeptical.

She heard a keening … it was Mr. Whitman, crying out from within his crystal house. As he screamed more forcefully, her belief grew, until it was three babies, ten men, a hundred women who would rise from death that night. As he writhed and screamed, making the most horrible noise she'd ever heard in her whole life, Maci believed and believed and believed. It was like a muscle in her, swelling as she flexed it over and over.

Why is Mr. Whitman screaming? He is the machine's "battery," he must sacrifice himself so that it can feed off his … what? His barbaric yawp? His "kosmic" mojo? The assignment of a spiritual wattage to Whitman's talent is the logical end of the novel's reductionist organizing principle. It would seem like parody if there was any trace of a smile, but there is only screaming and believing.

D. H. Lawrence famously wrote that Whitman "drove an automobile with a very fierce headlight, along the track of a fixed idea, through the darkness of this world," oblivious to everything not on his predetermined path. Perhaps, then, it is poetic justice that Adrian straps Walt into the machine and sends him on a collision course with the death he so brashly courted in verse. In the end, as befits a creation of magical literalism, the machine succeeds even as it fails. Like the disintegrating Aaron Stanz, the novel comes to rest, having nothing more for its overweening will to compel.