Many years ago, when I was studying the American Revolution in graduate school, I was shocked to find that the Founding Fathers were not very religious, or, rather, that they subscribed to “natural religion,” or deism, which located God in trees, streams, and flowers, but not in church or the Bible. They seemed hostile to organized religion, taking the view that established Churches, particularly the Catholic but Protestant ones as well, had seldom worked for the betterment of mankind and in fact were mostly captive to the interests of kings, aristocrats, and oppressors of the common people. They ridiculed the holy trinity as an irrational idea unsuitable for a self-governing republic. “Sweep away their gossamer fabrics of factitious religion, and [clergymen] would catch no more flies,” wrote Thomas Jefferson to John Adams. “We should all, then, like the Quakers, live without an order of priests, moralize for ourselves, follow the oracle of conscience, and say nothing about what no man can understand, nor therefore believe.” Adams agreed. He was disturbed—as late as 1817—that “a Protestant Popedom” was still doing its mischief in America. Religion, both men thought, was about life, not doctrine, and it boiled down to four words: “Be just and good.”

Benjamin Franklin spoke for most of the Founding Fathers when, near the end of his long life, he wrote to the president of Yale,You desire to know something of my religion. It is the first time I have been questioned upon it. Here is my creed. I believe in one God, Creator of the universe. That He governs it by His Providence. That He ought to be worshipped. That the most acceptable service we render Him is doing good to His other children. That the soul of man is immortal, and will be treated with justice in another life respecting its conduct in this. . . As to Jesus of Nazareth, my opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think the system of morals and his religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is likely to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupt changes, and I have . . . some doubts as to his divinity; though it is a question I do not dogmatize upon, having never studied it, and think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an opportunity of knowing the truth with less trouble.

Much later, as I read more widely and grew interested in the contribution of ordinary people to the emergence of this nation and its most admirable traits, I came to a very different understanding of the role of religion in the making of American democracy. I discovered that the first Great Awakening—the widespread religious revival of the 1740s—had fostered a sense of self-worth among common people, and led indirectly to their willingness to unite against the world’s mightiest nation several decades later. After the revolution, an outpouring of evangelical religion erupted, in which, as the historian Nathan Hatch has written, “the right to think for oneself became . . . the hallmark of popular Christianity.”

“The right to think for oneself.” That proposition may sound unremarkable today, but it was a radical notion 200 years ago. Traveling ministers in the early 19th century carried that message to working people throughout the country. The movement they represented—deeply democratic and, in its focus on personal revelation, at odds with Church hierarchy—would do more than anything else to spread Evangelical Protestantism and eventually make it the dominant religion in the nation. Let’s ride on the circuits traveled by three key figures in the transformation of American religious life who were determined to think for themselves and who saw themselves as members of Christ’s militia.

* * *

Born a slave in 1760, Richard Allen grew up in rural Delaware, where just after the revolution began he fell before the religious message of circuit-riding Methodists. “One night I thought hell would be my portion,” he recalled many years later. “I cried unto Him who delighteth to hear the prayers of a poor sinner, and all of a sudden my dungeon shook, my chains flew off, and, glory to God, I cried. My soul was filled. . . . My lot was cast.” At 20, after purchasing his freedom, Allen began a six-year religious odyssey. An itinerant preacher with no church, no pulpit, no salary, no license to preach, and no regular place to sleep at night, Allen worked as a woodcutter, wagon driver, and shoemaker as he traveled by foot over hundreds of miles topreach to black and white audiences in villages, at crossroads, and on farms, even into Cherokee country.

At 26, Allen became the Methodist preacher for free blacks in Philadelphia, where an act to abolish slavery had gradually taken effect even before the revolution was over. “I preached in the commons, [on the city’s fringes], and wherever I could find an opening,” he remembered in his autobiography. “I frequently preached twice a day, at 5 o’clock in the morning and in the evening, and it was not uncommon for me to preach from four to five times a day.”

It didn’t take long for Allen to see—in his words—“the necessity of erecting a place of worship for the colored people.” His idea was that black Americans just emerging from slavery needed independent black houses of worship because “men are more easily governed by persons chosen by themselves for that purpose than by persons who are placed over them by accidental circumstances.” This distinctly democratic vision contained the seeds of separate black churches—“a necessity,” Allen put it, “of separate and exclusive means and opportunities of worshiping God, or instructing their youth, and of taking care of their poor.”

By the standards of whites in the years after the revolution, this was presumptuous. How could men and women who had spent their lives in slavery and were barely literate create a church of their own? How could they conduct religious services, baptisms, marriages, and funerals? William Douglass, the first black historian of the black church movement, wrote that it was an “age of a general and searching inquiry into the equity of old and established customs,” a time when a “moral earthquake had awakened the slumber of ages,” causing “these humble men, just emerged from the house of bondage . . . to rise above those servile feelings which all their antecedents were calculated to cherish, and to assume, as they did, an attitude of becoming men conscious of invaded rights.”

And so it was, at 33, that Allen, knowing that black Philadelphians must “worship God under our own vine and fig tree,” saved money to purchase a lot in Philadelphia. Then he converted an old blacksmith’s shop into Bethel Church—the first independent black church in the North. This was 1793.

In September of that same year, Philadelphia—then the nation’s capital—was devastated by a yellow-fever epidemic. Hundreds were dying for lack of treatment, the poor were starving, and the dead lay everywhere in the streets while thousands of middle- and upper-class Philadelphians fled to the countryside. Allen stepped into the breach, along with Benjamin Rush, one of the few doctors who remained in the city. Recruiting other free blacks, Allen led his people forward as nurses, gravediggers, and drivers of death carts. Day after day, Allen and his followers—women and men alike—treated the afflicted, making notes on each case for Dr. Rush as they worked. Allen wrote that the oppressed free blacks of the city must act as Good Samaritans, succoring those who reviled and opposed them, because “the meek and humble Jesus, the great pattern of humanity, and every other virtue that can adorn and dignify men, hath commanded [us] to love our enemies, to do good to them that hate and despitefully use us.”

At 35, Allen was leading one of the largest churches in Philadelphia. A few years later he organized black Philadelphians to petition Congress to end slavery and revoke the detested 1793 Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slaveholders to claim fleeing slaves without so much as a sheriff’s warrant. At 45, his flock growing rapidly, Allen built a brick church to replace the old wooden blacksmith’s shop. By 1813 the new church was bursting with nearly 1,300 members attracted by Allen’s evangelical fervor, the Methodist “prayer bands” that met in homes on weekdays to help sinners search collectively for redemption, and summer “love feasts,” where emotions were openly and fully expressed in outdoor gatherings.

Then, in 1816, tired of fighting white Methodist attempts to make him knuckle under to their rules and even to put the pulpit of Mother Bethel in the hands of white preachers, Allen made a momentous decision: he would withdraw entirely from the white Methodist church. For many years he had preached that blacks were God’s chosen people, because like the enslaved Israelites fleeing Babylonian captivity, they were the ones who would have to redeem their sinful oppressors. When the white Methodists, still claiming control over Allen’s church, sent a southern white preacher to claim Allen’s pulpit, black worshipers clogged the church aisle and barred the intruder from ascending. Allen’s parishioners, 2,000 strong, supported his plan to establish their own denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal church—the AME that in future generations would produce so many national leaders and become the largest black church in the world, with churches in scores of countries. Within a year black Methodist leaders from Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware convened in Philadelphia and elected Allen their first bishop. The creation of the first autonomous black Christian denomination was as significant for black Americans as Martin Luther’s withdrawal from the Catholic Church was for his German followers 240 years earlier.

One black preacher from Baltimore wrote that “no one can imagine with what enthusiasm the colored people . . . were filled over these encouraging prospects.” A bishop who succeeded Allen captured the full meaning of the black declaration of independence. Taking his cue from the scriptural passage in Acts, “Stand up, I myself am also a man,” he wrote that white religious leaders were furious at Allen’s creation of a fully independent black denomination because it meant a loss of control over black Christians, whom they regarded as incapable of self-government and self-support. The “great offense,” the “crime which seems unpardonable,” wrote Allen’s successor, “was that [we] dared to organize a Church of men, men to think for themselves, men to talk for themselves, men to act for themselves.”

Allen always taught his parishioners that the last shall be first and the first shall be last. He wrote in the rules that would govern the independent AME Church that it would not repeat, in his words, the “spiritual despotism which we have so recently experienced.” He vowed that independent black Methodists would take a different course from that of white Methodists, “remembering that we are not to lord it over God’s heritage, as greedy dogs that can never have enough. But with long suffering, and bowels of compassion to bear each other’s burthens, and so fulfil [sic] the Law of Christ.”

Allen’s story captures one of the main developments in American religion in the decades of the early republic: spiritual striving and sacred community-building was going forward not under the tutelage of learned theologians and highly trained ministers but through the leadership of people with humble origins and, usually, almost no formal training, who rose to their positions simply because they could communicate with ordinary people about the Gospel. These independent ministers shared the Founding Fathers’ hostility to traditional organized religion, but not their skepticism about religious belief itself. Religious commitment grew rapidly in America in the early 19th century because ordinary people were discovering their spiritual gifts, because they were striding forward to follow the call they heard, and because thousands of other ordinary people were taking these spiritual impulses at face value rather then having them mediated through Church doctrine or the clergy. These ordinary people unleashed a torrent of religiosity that had been dammed up by the traditional dispensers of religious faith.

* * *

Yet when Richard Allen and his flock declared their independence from the high-handed white Methodists, they found themselves grappling with another aspect of a democratized religion—new voices for liberation within their own ranks that came from women.

One such woman, who sat in the pews of Mother Bethel, was Jarena Lee. She had been born free in New Jersey, and when she was seven she had been—like the child of many poor black parents—apprenticed to a white family. At 17, she came to Philadelphia filled with spiritual stirrings. There she was transformed by a passionate sermon delivered by Allen. “That moment, though hundreds were present,” she later wrote, “I did leap to my feet and declare that God, for Christ’s sake, had pardoned the sins of my soul.” Jarena shortly married another black minister and a few years later heard a voice. “Go preach the Gospel!” the voice said. “I immediately replied aloud, ‘No one will believe me.’ Again I listened, and again the same voice seemed to say—‘Preach the Gospel; I will put words in your mouth, and will turn your enemies to become your friends.”

That night Jarena Lee had a dream. In her sleep “there stood before me a great multitude, while I expounded to them the things of religion. So violent were my exertions and so loud were my exclamations, that I awoke from the sound of my own voice.” Lee had astounded herself at this ability to preach, and she knew the source of this inner power, which women were not supposed to possess. When she told Richard Allen that she had received the call to preach, that God had spoken to her, Allen explained that she could not preach from Bethel’s pulpit because Methodism had never provided for women preachers. Lee replied, “If the man may preach, because the Saviour died for him, why not the woman? seeing he died for her also. Is he not a whole Saviour, instead of a half one?” Allen would not yield, but he encouraged Jarena to use her spiritual gifts as a wandering gospeler. That she did for two years, walking deep into the countryside outside Philadelphia to spread her message.

But the voice telling her to preach within churches as well as in forest clearings and pastures wouldn’t go away. In 1819, she rose spontaneously during a Sunday service at Mother Bethel and words tumbled from her mouth. The crowded church fell under the power of her words. “God made manifest his power,” she recorded in her journal, “in a manner sufficient to show the world that I was called to labor according to my ability. . . . I imagined, that for this indecorum, as I feared it might be called, I should be expelled from the church.” But this time Richard Allen relented, opening Bethel’s pulpit to her, befriending her, and intervening on her behalf with other clergymen who adamantly opposed women preachers.

For many years, Lee crisscrossed the country, turning field, farm, and city street into sacred spaces when she could find no consecrated church that would allow her to preach. She often preached at interracial gatherings. North through New York and New England to Canada, south to Delaware and Maryland, west to Indian country, traveling on foot and by steamboat and ferry, she preached to thousands. In one year she logged more than 2,000 miles and delivered 178 sermons.

Though she was never ordained, Lee inspired people of all sorts, but especially black Methodist women. All black churches, like white churches, depended heavily on women—as teachers in church schools, moral cudgelers of wayward husbands, leaders of prayer meetings, and organizers of auxiliaries that created and supported church programs. But in gaining the pulpit, Lee broke a barrier that would not be duplicated in other denominations, black or white, until the 1970s and 1980s. Across this barrier strode other spiritually gifted black women. They stepped forward as living testimony to the democratic spirit of the era, dreaming, as Nathan Hatch has written, “that a new age of religious and social harmony would naturally spring up out of their efforts to overthrow” the old rules—including the conventions of gender. By reaching the pulpit and carrying the Gospel message outdoors, women such as Lee reinforced the idea that ordinary people, whatever their gender, were repositories of religious faith and could be spiritual leaders of similarly humble people.

* * *

Another captain in Christ’s militia was Lorenzo Dow. Dow was of old New England stock—poor stock—one of the many who struggled with the rocky, thin soil from which farmers extracted a meager living. Sickly and solemn, he found little joy in his youth—and certainly little from the droning, old-style minister in the local church. Then he fell under the spell of a traveling Methodist preacher. His account of his conversion—his rebirth—sounds much like those of others who fell beneath the Methodist scythe. “The burden of sin and guilt and the fear of hell vanished from my mind, as perceptibly as an hundred pounds weight falling from a man’s shoulder,” he remembered. “My soul flowed out in love to God, to His ways and to His people; yea, and to all mankind. As soon as I obtained deliverance, I said in my heart, I have now found Jesus and His religion, but I will keep it to myself; but instantly my soul was so filled with peace and love and joy, that I could no more keep it to myself, seemingly, than a city set upon a hill could be hid. Daylight dawned; I arose and went out of doors, and every thing I cast my eye upon, seemed to be speaking forth the praise and wonders of the Almighty.”

Lorenzo Dow was 16 when he experienced this conversion. A year later, he felt compelled to speak. His parents reproved him, and Methodist ministers told him he was too young to venture forth preaching. But the messengers kept entering his dreams, much as they disturbed Jarena Lee’s sleep. One night John Wesley, the founder of English Methodism, appeared in Lorenzo’s sleep. “You are called to preach the gospel; you have been a long time between hope and fear; but there is a dispensation of the gospel committed to you. Woe unto you, if you preach not the gospel.”

And preach the gospel he did. Dow left home at age 18 astride a horse. For 40 years, he hardly put his head down in one place. He visited every crossroads, village, and town from the Canadian forests to the Louisiana bayous—along with three itinerating trips to England and Ireland. His daily journal, kept over many years, tell us that it was nothing unusual for him to ride 70 to 85 miles in a day, to walk 20 to 25 miles on foot, and to preach up to a dozen times, often wrapped in a long dirty cloak and wheezing from the asthma he suffered from all his life. In a single year, 1805, he traveled some 10,000 miles by foot, by horse, by barge and boat. No one commissioned him to preach; and he belonged to no church. But he touched the hearts and minds of hundreds of thousands of Americans. However disparaged by Methodist leaders or local officials, there is no doubt that by his death in the 1830s he was the most widely known—and perhaps best traveled—man in America.

The established Methodist church leaders, more conventional and polite and jealous of their own authority, hated Dow and warned people about him. But on the camp-meeting circuit he converted so many people to Methodism that the church authorities couldn’t challenge his right to speak, even though they didn’t invite him into their churches. These camp meetings were something akin to Woodstock in 1969—mass gatherings of people who, dawn to dusk and even late into the night, reveled in outpourings of religious ecstasy, provoked by song and folk music, by stomping and writhing and groaning, by thundering Methodist preachers cudgeling people to confess their sins and get straight with Jesus. Dow might splinter a chair on the floor for effect, pick out a notorious sinner in the crowd and excoriate him mercilessly, and arouse those who flocked to hear him into fits of religious ecstasy.

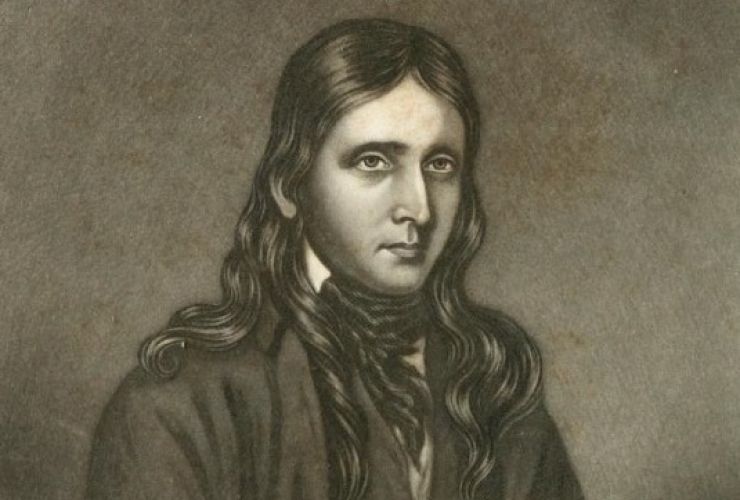

Thousands listened to this man with a weather-beaten face, long hair parted like a woman’s, eyes flashing, clothes a mass of rags, a big toe protruding from a moccasin. They said he was the most memorable preacherthey had ever heard. And he harvested converts to Methodism as farmers harvest wheat.

The camp-meeting performance was Dow’s path to a national reputation. But his message was at least as important. Dow’s enormous power lay in his militant egalitarianism and his understanding of common people. He may have been crazy, but always he was the roving messenger of spiritual equality. In a country born in revolution and founded on the notion that all men are created equal, he warned that concentrated power and ill-gotten wealth were a great beast loose in America. He was, as Nathan Hatch has put it, “a folk genius . . . projecting a presence that people found inviting, compelling and authoritative.” He insisted that God made no distinctions between rich and poor—indeed that the rich were less likely to be heaven-bound than the dispossessed. He railed against tyranny, social pretension, aristocratic airs, the professions of law and medicine. He told common people that they were sovereign, that they must stand independent, that they must think for themselves, take matters into their own hands, and fight all those who were ever ready to oppress and exploit them.

* * *

Richard Allen, Jarena Lee, and Lorenzo Dow were three of Christ’s American lieutenants: they came from nowhere and grew up as outsiders, but they rose to Christianize America in the half century after the revolution—and to Christianize it on the basis of a democratized Protestantism. By the time they were laid in their graves—Dow in 1834, Allen in 1842, and Lee in 1851—the evangelical churches, Baptists and Methodists primarily, ruled American religious life. Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and Quakers had all been eclipsed. On the eve of the American Revolution about 1,800 Christian ministers preached from their pulpits. By 1845, nearly 40,000 built Christ’s militia, and two thirds of them were Baptist or Methodist.

Looking back, we see Allen, Lee, and Dow as skillful and magnetic leaders. But those stiff words would have turned them away. They would have put it differently: they were God’s messengers, who knew that the most virtuous people in the nation were the common people and that most of the rich and powerful could no more reach heaven than a camel pass through the eye of a needle.