I received my first lesson in political philosophy from my father, who passed away this September. Though he never graduated high school, he earned his graduate degree by growing up a deeply chocolate Puerto Rican man in the 1960s and ’70s. He taught me to never stand for being tolerated—because all “toleration” means is that people are willing to deal with you for the moment, not accept you for the long term. He taught me that my dignity should demand the full acceptance, respect, and even love from my co-citizens. This was a radical idea to me. Growing up in the Reagan years and coming of age in the Clinton era, it seemed to me that racial toleration was the going thing—white toleration would solve racism. The kicker was that Blacks just needed to learn to be tolerable.

Coming of age in the Clinton era, it seemed to me that racial toleration was the going thing—white toleration would solve racism.

But my father was right. Those of us rich in melanin needed a better word—toleration is something bestowed by other people. I now see police murders through this lens, occurring when the thin, invisible line separating tolerable from intolerable is crossed by the Black person.

• • •

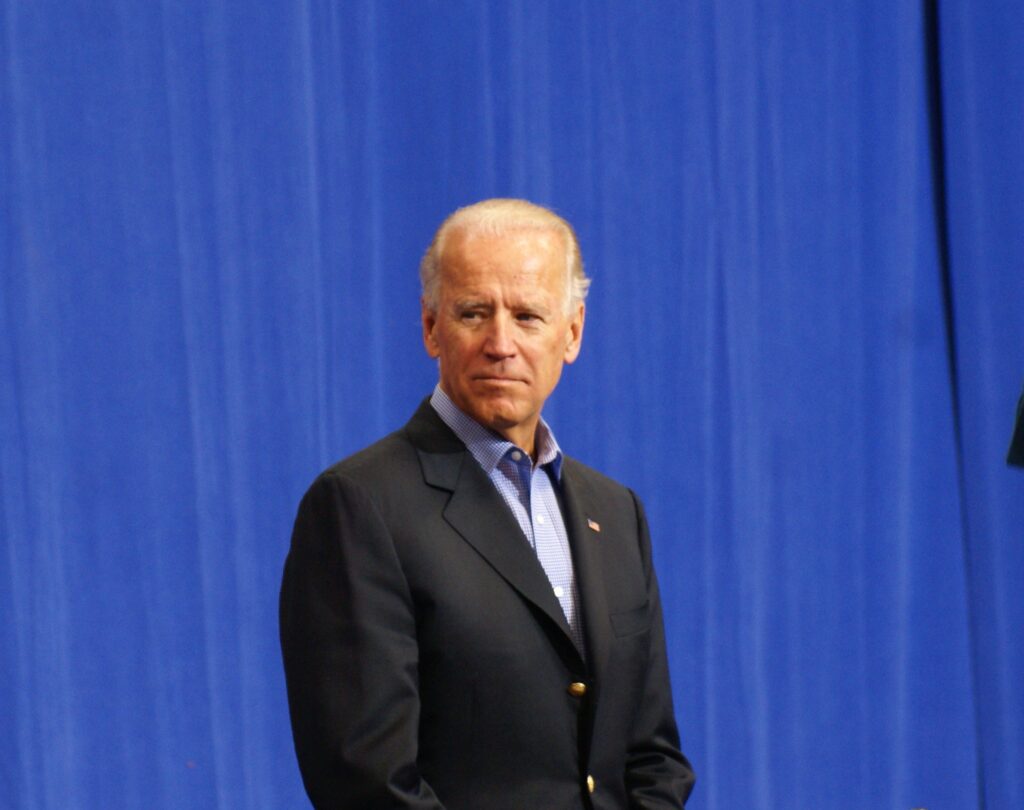

This winter and early spring, a time usually meant for hope and renewal, I watched with dismay as the Democratic Party’s primary season began to reveal a result that I felt was ruinous, incapable of heading off a genuine disaster being managed by Donald Trump. Out of the largest and most diverse field of contenders in history—including two Blacks, one Latino, one Asian, and six women—the party nominated a seventy-seven-year-old, moderate white man. This was the best the United States could imagine. But I wasn’t shocked solely because Joseph R. Biden is an OWG in a #MeToo and #BLM world. Biden also came with significant racial, and even racist, baggage.

Following Biden’s nomination, I first found myself in a low-grade state of rage (though I must admit that, as James Baldwin said, to be Black and conscious in America is to live in a state of rage). Many of my more moderate friends found this rage difficult to fathom—maybe because Biden had shown that he was tolerant of Black people.

Reagan waged war on Black welfare queens, Black crackheads, and their crackhead babies—the Blacks that white Americans found intolerable.

In 2007 Biden showed his tolerance when he called Barack Obama an “articulate guy.” Biden was tolerant because every time that his role in the 1994 crime bill that devastated Black communities arose during the Democratic debates this year, he stomped his foot and declared that he was not a racist. Instead, he contended, he should be congratulated for working across the aisle—as if partnering with retrograde neo-confederates somehow proved him a racial progressive. Biden showed he was tolerant because he had the liberal audacity to school Black television personality Charlamagne tha God on the nature of Blackness. I thought it was bullshit. I was not interested in being tolerated that way. To my mind, there was Black blood on Biden’s hands.

As is now well known, the 1994 crime bill that Biden had helped usher in had insidious and long-lasting ramifications for U.S. policing. Biden stood on the floor of the Senate and, as a liberal Democrat, entered into a kind of spiritual commune with U.S. racial suppression that had typically come from the right. Scholars such as Vesla Weaver and Michelle Alexander have helped us understand that the growth of the carceral state emerged as the conservative response to the civil rights victories of the 1960s. If Blacks could not be stopped from gaining rights, then the deployment of law enforcement would at least curtail the extent of their rights. In her now widely accepted formulation, Alexander called it the new Jim Crow era. That conservative backlash—or frontlash, as Weaver dubs it in recognition of its creative and anticipatory nature—carried through the Nixon years and into the Reagan years as he waged war on Black welfare queens, Black crackheads, and their crackhead babies—the Blacks that white Americans found intolerable.

Along with Bill Clinton, who brought the Democrats to political power in 1992 after selling himself as the blackest white person in America, Biden brought Nixon and Reagan to the left. As Bill Clinton promised to change welfare as we knew it, and Hillary Clinton leaned into the racist super-predatory theory that warned good Americans of the threat of young Black men, Biden argued that beefing up law enforcement was the only reasonable response to these dangerous youths who were gonna knock our treasured women over the head and snatch their necklaces. (He did not speak explicitly of race, but dog whistle was unmistakable.) The bill amplified the already escalating militarization of the police.

Forgiving Biden for the 1994 crime bill is not an option. But there is another ethical choice.

This year Biden reentered the political foreground just as the nation was erupting yet again in protest of extrajudicial police murders of Black people. George Floyd’s murder pushed the United States to its limit. People imprisoned in their own homes as their government botched pandemic response began to take seriously the idea of defunding the police. In other words, they began to deconstruct what Biden helped build—yet the Democratic Party decided to bank on him anyway. Why would we think that the hands that wrote that bill could be entrusted with our future? How could I accept Biden—the embodiment of white toleration of Black people?

• • •

In recent days I have thought about my father’s lesson and the directionality of our words. “Toleration” implies something I am to receive from someone else. That makes me reliant and dependent on the will of others, a waiter and receiver. What if we need to take the words into our own hands, words that originate in our own civic hearts?

There is a word that Black and brown people are always expected to make good use of and, I admit, a word we seem to be super-ready to deploy during times of civic warfare. That word is forgiveness. Now, I have found myself wondering if I need to forgive Biden. After all, we needed Trump replaced and Biden got the job done. I have already spent every day of the past four years living with rage in my heart.

But this truth puts me and likeminded Black Americans in a real bind. I know Biden is responsible, even if from a remove, for a lot of Black death. I do not want to forgive Biden for his undeniable sins: the terrorism his policy has helped bolster, his innumerable “gaffes” (as the press politely calls them) about who is Black, why Black children need to be read to more often—and on and on. In fact, I still choose to actively condemn him.

I can tolerate Biden because I hold him accountable for his past actions while choosing to see that he wants to aim toward decency.

But I also perceive that Biden is possibly changeable, that he at least possesses the intellectual perspicacity to endure the idea of transformation. Not only does Trump lack such perspicacity, he has blatantly shown that he has no interest in developing it. The only things he bothers to be honest about are his contempt toward Black and brown people and his sneering disdain for women who are not sleeping with him. Trump deserves nothing but unrelenting moral condemnation. The choice between him and Biden is not that hard once you grasp this basic fact.

So while I reject forgiveness, I choose to be guided to a second ethical position: toleration. Not the toleration white people hold for Black people—which, as my father understood, is arbitrary and one directional—but a toleration of hope and reciprocity. I can tolerate Biden because I hold him accountable for his past actions while choosing to see that he wants to aim toward decency. I choose not to be cynical about his choice of Kamala Harris for vice president. I choose to believe he is ready to be transformed by the times, his peers, and the mandate given to him in defeating good ol’ white supremacy. I can accept Biden for the purpose of dealing with him for the moment. All things considered, I think he deserves this much; he has proven himself increasingly tolerable. One day I might come to fully accept him and even, in my civic and moral heart, love him.