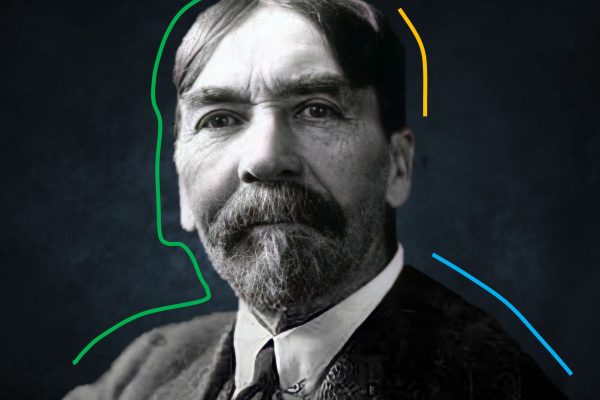

The Founding Fathers are a perennial source of both wisdom and controversy. Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has taken pride of place in these public debates in recent years, thanks in part to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical and Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography. In this interview, Michael Busch speaks with journalist and economist Christian Parenti about his new book Radical Hamilton: Economic Lessons from a Misunderstood Founder. They discuss how we still get Hamilton wrong and what we can learn from him about state building, economic planning, and the necessity of government action.

Michael Busch: You published Radical Hamilton in August with Verso Books. Let’s start at the beginning: Who was Alexander Hamilton? Why did you write this book?

Christian Parenti: Hamilton was a Revolutionary War soldier, advisor to George Washington, and major Federalist politician who played an important role in framing the U.S. Constitution and became the country’s first Secretary of the Treasury. He created the country’s modern financial system and central bank. Less commonly known, he also laid out a plan for government-led industrialization—that is to say, a plan for wholesale economic transformation.

I wrote the book by mistake, because I stumbled upon Hamilton’s often name-checked but rarely discussed magnum opus, his 1791 Report on the Subject of Manufactures. At first the plan was to just republish the Report with an introduction. But that grew into this book.

Cast by most historians as the patron saint of free markets and financiers, Hamilton actually launches an attack on Adam Smith and laissez-faire economics.

As I read up on the Report it became clear that there were major omissions and misunderstandings about Hamilton’s political economy and its role in the course of U.S. economic development. Cast by most historians as the patron saint of free markets and financiers, Hamilton actually begins the Report with an attack on Adam Smith and laissez-faire economics. He then goes on to present a sweeping program of transformation-oriented economic planning. This is totally at odds with the mainstream story of American capitalism and Hamilton’s place within it. Most books on Hamilton do not address Hamilton’s vision of a planned economy.

MB: Hamilton has enjoyed quite a revival recently. There’s the musical, obviously, but he has also been the subject of renewed scholarly interest in recent years. Can you talk briefly about how your work stands in relation to the body of work done on Hamilton over the last decade or so?

CP: The book is not a biography, so I was more interested in the literature on the Revolution and the Early Republic than on Hamilton per se. In fact, the historians whose work I use most are actually pretty hostile to Hamilton—for example, the excellent Woody Holton.

In soliciting endorsements for the book, I tried to curate something of a private joke by getting endorsements from a widely disparate set of scholars. Anyone familiar with the literature on the American Revolution and early republic should be at least a little surprised to see a book endorsed by Holton (a progressive historian of eighteenth-century social movements) and Richard Sylla (an economic historian specializing in finance, professor at a leading business school, and in no way a man of the left ), not to mention Marcus Rediker, a leading Marxist historian of the eighteenth century who takes a more internationally oriented approach to the study of capitalism.

Hamilton presents a sweeping program of transformation-oriented economic planning. This is totally at odds with the mainstream story of American capitalism and Hamilton’s place within it.

The point of my private joke is to suggest something beyond the classic “aristocracy vs. democracy” debate that too often frames discussions of the Founding, the Constitution, and the Early Republic. I argue that a third agenda also operated: the struggle for national survival and state making. As I read the evidence, the 1780s saw profoundly destabilizing, elite, self-dealing gangs operating at all levels: local, state, and national. Hamilton’s struggle was, amidst spiraling socioeconomic and military crisis, to build a state that could drive an economic transformation, that would in turn ensure the survival of that state.

The book thus attempts to drill down on government’s role in what Charles Post has called the “American road to capitalism.” Hamilton the state builder helps us understand the real relationship between government power and capital within the process of capitalist industrialization.

Michael Busch: In the book, you argue that the Revolutionary War was formative for Hamilton, though not in the ways we have been led to understand. What was Hamilton’s experience of the war, and how did it shape his political economic thinking?

Christian Parenti: Hamilton begins as a frontline officer, but after about a year and a half in combat he accepts a position on George Washington’s staff. From that vantage point, Hamilton gets a broad overview of the conflict as a logistical, economic, and political process. He quickly sees how totally dysfunctional things are and that the central problem is a disunited and weak government.

The thirteen colonies have come together under the Articles of Confederation, a loose security pact, and Congress, the only national institution along with the Continental Army, does not even have the power to tax. It must request money from the states. The states do not always pay up. When they do, they sometimes try to direct resources exclusively to their own military units. For example, Pennsylvania sends cloth to Washington but asks him to distribute it only to the Pennsylvania line. In that example the shipment of cloth had already been looted by desperate citizens before it even reached Washington’s command. In every aspect of the struggle there are major coordination problems and a dire lack of resources.

The left should take Hamilton seriously, not literally. And we should never get too positively or negatively attached to these Founders as people.

Amidst this, Hamilton gets a frontline education on the importance of national credit, economic coordination, and manufacturing capacity. And, he begins to sketch the outline of what Charles Tilly and later social scientists would call a “fiscal military state”—a government that can create economic conditions through borrowing, taxing, investing, and guiding the larger national economy toward growth, which, in turn, pays for the administrative and military capacities the state needs to defend its sovereignty internationally and against internal threats. (I am very critical of modern America’s bloated military industrial complex, but in the 1770s and 1780s the situation was very different.)

The Republic’s survival was not guaranteed by military victory, nor by experiments in democratic government alone. It required a profound economic transformation that took decades to achieve. And that economic transformation did not just occur naturally—it had to be produced by a sophisticated, innovative, and sweeping program of government action.

MB: Toward the war’s end and immediately following it, the United States enters the so-called critical period, which sees existential threats to the fledgling country in the form of mutinies, rebellions, and economic turmoil. How did this period influence Hamilton’s thinking?

CP: The war has contradictory economic effects. It produced widespread destruction, but it also provided tremendous economic stimulus and created an economic boom. The three armies had ravenous appetites for everything: weaponry, boots, paper, salt, livestock, fodder, firewood. This consumption drove production and investment, much of it paid for with vast emissions of paper money. All of this created an inflationary boom. But when the war ends, the economy collapses into a depression about as bad as that of the 1930s. Investment dries up, production and consumption contract, and huge often unpayable debts come due.

The classic “aristocracy vs. democracy” debate that too often frames discussions of the Founding, the Constitution, and the Early Republic. I argue that a third agenda also operated: the struggle for national survival and state making.

At the same time, a plethora of small military conflicts emerge. The governments of Georgia and South Carolina are fighting Maroons—armed, self-emancipated people of African descent living in autonomous communities. From Georgia up to the Ohio territory, Native Americans and settlers are fighting. This combat is particularly brutal in what is now Kentucky. Rival groups of white settlers clash in what is now Eastern Tennessee and in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, commercial conflicts are breaking out on the coast. New York imposes crippling tariffs on New Jersey and Connecticut. Maryland and Virginia struggle over navigation and trade on the Chesapeake.

Exacerbating all this is an environmental crisis. In 1783 there are two massive volcanic eruptions—one in Japan, the other in Iceland. The latter goes on for almost an entire year. Emissions from the eruptions create a cooling effect across parts of the Northern Hemisphere. In the Northeastern United States this means harsh winters, catastrophic springtime flooding, and cold, wet summers. All of this hurts crop yields, which only exacerbates the economic crisis.

Finally, the critical period involves brutal, deflationary, debt-fueled austerity. Congress and the states have borrowed heavily, and by the mid 1780s they’re attempting to extract enormous amounts of money from increasingly stagnant economies. Taxes go up and public spending is cut. This increases the economic burden on common people, hampers investment, constricts consumption, and drives down prices. As the value of money suddenly increases, people start hording it. Private sector investment contracts, which hurts economic growth, causing further deflation.

All of this culminates during the summer of 1786 in Western Massachusetts, where a widespread foreclosure crisis turns into an almost year-long guerrilla war known as Shays’ Rebellion. Named for Daniel Shays, who had been a captain in the Continental Army, and then helped lead the uprising, these rebel farmers actually called themselves “Regulators.” To stop foreclosures and evictions, they closed down the courts and threw out all the judges and the lawyers. State authorities attempted to muster the militia, but the units either refuse to mobilize, or mobilize and then dissolve—or, worst of all, switch sides and join the rebellion!

Economic transformation did not just occur naturally—it had to be produced by a sophisticated, innovative, and sweeping program of government action.

In desperation, the merchant elite and the government of Massachusetts create a privately funded army. During the bitterly cold winter of 1786–87 there is on and off combat including two actual force-on-force conventional battles that even involve some artillery. But mostly the fight takes the form of ambushes, small shootouts, assassinations, beatings, arrests, arson, threatening “night letters”—basically guerilla terror tactics and counterinsurgency.

As Shays’ Rebellion is being mopped up in late May 1787, the Constitutional Convention convenes in Philadelphia. The Convention is a direct response to the panoply of crises that arise in this period. In short, the whole revolutionary project is sinking into economic stagnation, political fragmentation, and military crisis. To survive, at least in the view of federalists like Hamilton, the central government has to be reorganized and re-founded.

MB: The Federalist Papers are published following the Constitutional Convention. They argue for ratification of the new constitution by the sometimes-reluctant states, and Hamilton is one of the principal authors. What do the Federalist Papers tell us about Hamilton’s political theory of the nation-state and the individual American states?

CP: The papers, particularly those written by Hamilton, recognize that the state creates economic conditions: it does not merely react to them. Keep in mind, Adam Smith’s laissez-faire arguments against government intrusion into the market are widely popular at this time. In contrast, Hamilton saw government as an essential, perhaps even primary, economic agent. It does not merely respond to the private sector but is a primary mover of, and within, what had been cordoned off as the “private sector.” Hamilton realized that if the new American government united, it could create economic conditions favorable to both internal economic development and its place within the international state system. Rather than passively receiving terms from the great powers, as is the fate of so many post-colonial economies today, it could enforce its will in the realm of international trade. Hamilton was also very clear that such an outcome would not develop “naturally” by way of Smith’s invisible hand. It had to be planned and actively pursued by the state.

Hamilton’s Federalist papers recognize that the state creates economic conditions: it does not merely react to them.

As for the thirteen states governments, Hamilton is very suspicious of them. He stood in opposition to the state’s rights lobby, the Jeffersonians, or the Democratic-Republicans. This is not just a Southern set of interests there were also ruling cliques in Northern states, merchants and landlords, who were concerned with maintaining states’ rights and business as usual. For example, the clique surrounding New York Governor, George Clinton. And, there are Southern Federalists, like John Marshall. But the localist agenda is primarily championed by Southern elites who are guarding their economic and social prerogatives—owning human chattel and vast, often un-taxed, lands.

The elite of South Carolina and Virginia were content exporting raw materials and importing foreign manufactured goods, French wines, and British books. Southern elites worried that the shipping and nascent manufacturing interests of the populous Northeast might dominate the powerful new central government; they worried this potential leviathan outlined in the Constitution would be expensive, and that their property – land and slaves – would be heavily taxed to pay for it. Southern elites also worried that the new state would inhibit their right to conduct untaxed free trade; and that it might even attack their right to own, import, and sell slaves. When the question of the slave trade came up at the Constitutional Convention, John Rutledge of South Carolina, essentially threatened secession in defense of the slave trade.

Keep in mind, the richest people in the country were all white Southern elites. This was true even as about a third of white southerners were landless, desperately poor, often semi-vagrant. (Keri Leigh Merritt’s 2017 book, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, is really good on that contradiction.)

In protecting their locally sanctioned prerogatives, the states right advocates invoked the ancient Greek city states, arguing that only small political units could be truly accountable to the people. Hamilton swept this argument aside in Federalist No. 9, pointing out that even the smallest U.S. states were already too big to be face-to-face democracies modeled on Athens. The Republic had to build democracy on a new and larger scale, using modern means of communication and transportation. In other words, economic development would effectively shrink space and facilitate practice of democratic politics over an extensive area.

Hamilton saw government as an essential, perhaps even primary, economic agent. If the new American government united, it could create conditions favorable to both internal development and its place within the international state system.

Hamilton’s fundamental concern was that two sovereignties could not simultaneously co-exist within the same territorial limits. It would, he predicted, lead to war. And, indeed it did. The Civil War was the result of conflicting sovereignties existing in a shared space. The Confederates wore gray because that was the color of state militia uniforms. In general, Hamilton held state governments in low regard, seeing them as catch basins for second-rate men. The states’ rights camp argued that a central government with a standing army would lead to despotism. Hamilton argued the opposite: that small, fragmented sovereignties would lead to frequent warfare, a veneration of the military, the worship of officers, and thus a political culture fertile for despotism.

At the Convention, Hamilton went so far as proposing that the states be liquidated and replaced with federal electoral districts. Sounds crazy, but without states—and the Electoral College which flows from them—we would not have recently suffered twelve years of minority rule under George W. Bush and Donald Trump, both of whom lost the popular vote.

MB: It strikes me that the Hamiltonian theory of political economy in some ways anticipates Karl Polanyi’s idea that the private sector is fundamentally dependent on government for its continued existence. In this light, your book understands the Constitution as a kind of toolkit for state-driven economy building. How does the Constitution do this—and in particular, how does it empower government to take economic action on behalf of the people?

CP: Most literature on the Constitution looks at how our government works: checks and balances, the three branches of government. I looked instead at what this government does. And in Article 1, Section 8, the Constitution reads as an outline for the developmentalist, or dirigiste, state.

For Hamilton, the Republic had to build democracy on a new and larger scale than the Greek city states, using modern means of communication and transportation.

There is a lot of seemingly prosaic and wonky stuff in Article 1, Section 8, so it is usually overlooked. But add it all up and you see a rudimentary but powerful policy toolbox for driving economic growth and transformation: taxing and spending, coining money, setting weights and measures, creating a post office and under its authority building transportation infrastructure, controlling bankruptcies, controlling intellectual property rights, regulating foreign trade and commerce between the states, controlling development of federal lands, building a navy and military, supporting scientific research, and serving “the General Welfare.”

The Postal Clause empowers Congress to establish post offices and, crucially “post roads.” Benjamin Franklin wanted an explicit mention of canals but was defeated. Yet that little word, “roads,” meant that during the early nineteenth century the post office acted a huge public works agency—huge by the standards of that day. By 1830 it had built 115,000 miles of post roads, which is to say most of the country’s major roads. And it cleared and made navigable all the major rivers. The post office plays an important role even into the twentieth century. Early aviation was heavily subsidized by the federal government contracting the nascent airlines to carry the U.S. mail.

The General Welfare Clause is one of the most important and contentious clauses in Article 1, Section 8, because it is so potentially broad. Jefferson and the small government, low-tax, states-rights crowd saw this and immediately took issue with it. Jefferson complained to Washington that under the General Welfare clause, Congress could take almost anything under its management in the name of this clause. Jefferson’s fear was correct, the clause potentially opens the door for all sorts of very progressive state planning, public ownership, and socio-economic transformation. The phrase, general welfare, is so broad it could mean almost anything that is socially useful.

MB: Can you talk a little bit about how that connects with the fight over slavery and the slave trade in the United States?

Hamilton’s fundamental concern was that two sovereignties could not simultaneously co-exist within the same territorial limits. It would, he rightly predicted, lead to war.

CP: The Constitution never uses the word “slavery,” but it both protects and limits slavery. Protection comes in the form of the three-fifths clause, which counts the enslaved for the purpose of allocating congressional seats and gives slave states more power than they might otherwise have. Slavery is also protected by the extradition clause upon which the fugitive slave laws will rest. This becomes very contentious in the run-up to the Civil War, of course. The Constitution also protects the international slave trade until 1808. But it also opens the door for suppression of the slave trade thereafter: it does not specify any property qualifications, gender restrictions, or racial restrictions on federal voting and office holding. For the eighteenth century, that’s actually pretty progressive, much more progressive than most of the state constitutions were.

MB: Fast forwarding a little bit: Hamilton becomes secretary of the Treasury, and straight away he issues a series of reports that outline plans for American economic development. As you noted above, Radical Hamilton focuses particularly on the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, which you say is often overlooked and misunderstood. Why is that report important?

CP: The report is often mentioned but rarely discussed in any detail. Interestingly, it opens with a direct attack on Adam Smith and laissez-faire. Keep in mind, Thomas Jefferson called Wealth of Nations the best book in existence. It was very popular among the Founders.

In his dissent against this orthodoxy, Hamilton argues that free markets only work if your national economy is already wealthy and powerful. In other words, if you are Great Britain. But for a fragmented underdeveloped economy emerging from war and colonial dependence, free trade is a disastrous mirage. The “invisible hand” will not deliver development. Government has to conceive and execute a plan for that to happen.

Hamilton argues that free markets only work if your national economy is already wealthy and powerful. In other words, if you are Great Britain.

After attacking Smithian fantasy, the report, in a touching appeal to sectional unity, attempts to placate the agrarian South by arguing that a program of industrialization will benefit the producers of raw materials by creating new markets for these products. Next, Hamilton explains how a manufacturing-based economy will increase national wealth by increasing labor productivity. This new wealth will promote a broad prosperity that improves livelihoods, and crucially will provide the economic basis for the government to protect itself against external and internal threats. Finally, Hamilton lists what he calls “the Means Proper” the policy toolkit of the developmentalist state. In my opinion, the term “Means Proper” should be as common in the American political lexicon as “representational government” or “due process.”

In isolation, each of these “means proper” policy tools are not particularly interesting. But put them all together, use them in concert as part of a coherent plan, and they become very significant. The tools mentioned in the report include tariffs or taxes on imports, because these will both raise revenue and protect domestic “infant manufactures” from foreign competitors. It calls for outright bans on some types of imports and bans on exports of some strategic raw materials. But it also wants tax breaks for strategic sectors, firms, and classes of materials and the tax-free import of essential and difficult to procure raw materials.

The report advocates for subsidies to strategic types of industry, a nationally standardized system of measurements, a government-run nationwide system of payments and transfers, public prizes for new inventions, and a system of government backed patent and copy right protection for intellectual property. It calls for the recruitment of foreign labor and technical expertise and wants public support for the aggressive aquation of foreign technology. (This is the ruthless subtext of the patent protection section: “bring us stolen industrial knowledge and we will protect you.”) Indeed, Hamilton and Assistant Secretary of Treasury Tench Coxe actively pursued industrial espionage. The report also urges public investment in, and the creation of, scientific institutions and laboratories, as well as public ownership and construction of transportation systems. Last, the report proposed a national planning board. Though it was not adopted, Hamilton was sketching the embryonic form of an agency akin to Japan’s famous Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

According to Hamilton, the “invisible hand” will not deliver development. Government has to conceive and execute a plan for that to happen.

The typical story is that the report was “rejected,” but that is not entirely accurate. While there was much opposition, key parts of it were taken up by the federal government. And many states pursued the report’s agenda and used versions of the Hamiltonian “means proper” as best they could—New York state’s massively successful public work on the Erie Canal being the most prominent example.

After Hamilton dies, Henry Clay of Kentucky becomes developmentalism’s most prominent champion. The agenda of government-led economic transformation via “the means proper” becomes known as “the American System.” Soon this American political economy is taken up by Europeans including Friedrich List, who arrives from Germany in the 1820s. Very influenced by these ideas, List returns to Germany in 1833, and in Germany the American system soon becomes “the National System” and is central to the story of German industrialization and the founding of the German Historical School of Economics.

The Japanese also take up these ideas as part of the Meiji Restoration. By the 1850s, Western powers, including the United States, are using gunboats and the ideology of free trade to force their way into Japan’s closed economy and society. Facing conquest and colonization, Japan defensively adopts a forced march toward industrialization and modernization, and they did so, to great success, by using huge doses of Hamiltonian political economy.

MB: I want to turn to the critics of your focus on Hamilton. William Hogeland argued in these pages that Hamilton’s embrace of militarism and the concentration of American wealth are deeply troubling, and he suggests that Hamilton’s legacy hardly offers a basis for leftist politics. What do you make of this assessment?

CP: The left should take Hamilton seriously, not literally. And we should never get too positively or negatively attached to these Founders as people. Loving them or rejecting them—both paths are adolescent. But we do need to understand American history—seeing how the present is shaped by and flows from the past. Luckily there are a lot of people out there who are capable of such nuance.

I like Hamilton’s harsh, unsentimental realism, and state-focused political economy. Those are two things the U.S. left needs much more of.

I like Hamilton’s harsh, unsentimental realism, and state-focused political economy. Those are two things the U.S. left needs much more of. At the time, Hamilton’s embrace of militarism was largely defensive and made perfect sense in terms of sovereignty and national survival. But we don’t live in the eighteenth century; our America is a totally different beast. We need to be against militarism. But that seems pretty obvious.

In the beginning of the book I compare Hamilton to Simón Bolívar who, in South America, also attempted to create a liberal, republican, developmentalist state of continental size. The Bolivarian project fragmented. As a result, in Latin America economic development was delayed and distorted by outside powers. That is a cautionary tale. It was not at all inevitable that the United States was bound for high standards of living and political stability. The American project of state formation could have easily fragmented: indeed it almost did on several occasions. Its industrialization and economic development is not to be taken for granted. Had the nation fragmented, Alabama would today probably be a totally underdeveloped, politically unstable, banana republic with bad roads, no state university system, no environmental laws, no minimum wage. Americans take for granted the historical course of our economic development, but that is a mistake. In politics, nothing is inevitable.

I do not agree that Hamilton embraced the concentration of wealth as such. Rather he had a very realistic view of how to harness elites to the project of state formation. He knew the money interests would ride parasitically with that project or against it and he would rather have them on his side. Hamilton was not a “progressive” in any modern sense, woke or liberal. He was homo publicus: a creature of the public sector and the state. He knew that the future held crises, both internal and external, that could only be met by a strong and capable government. He was a realist. And he helped pioneer modern economic planning and conscious economic transformation.

It was not at all inevitable that the United States was bound for high standards of living and political stability. Its industrialization and economic development is not to be taken for granted.

As for the U.S. left and its “basis,” we need to get real. The good and bad news is this: a growing section of increasingly class-conscious formations are struggling against plutocracy and reaction on the right, but also within “the left” against an inchoate field of woke, foundation-funded, cliques, networks, and nonprofits that push moralizing, language-fixated, cancel-culture, and in the face of ever-rising economic exploitation and inequality remain almost totally powerless. We need harsh, grown up, realism about the state, class power, and political economy, so that we may, as Marx and Engels put it, “face with sober senses” our real conditions of life and transform them.

It is perhaps important to know that this book is informed by my previous books, particularly The Freedom and Tropic of Chaos, and by a decade working as a foreign correspondent, much of that in war zones and failed states. I do not take functional public institutions, good roads, rule of law, peace, electricity for granted. I reject the anarchist, ultra-leftist, and liberal reflex to see the state as only bad. Yes, the state is repressive and can become genocidally despotic. But the absence of a state is just as bad, usually worse. Having researched firsthand the desperate struggles of workers in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Cote D’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, the DRC Congo, and other such places, I can assure you that a collapse of public order does not open the way to democratic politics. A functional government is a necessary precondition for any civilian politics of the left. I get the impression that many people on the U.S. left are still very unclear about such questions.

MB: You end the book by gesturing towards a “Green Hamiltonianism.” How might Hamilton’s political economy influence our efforts to tackle the climate crisis?

CP: Dealing with the climate crisis requires euthanizing the fossil fuel industry and building out a new clean energy infrastructure. That is a massive project of green reindustrialization. How are we to do this?

Hamilton was not a “progressive” in any modern sense, woke or liberal. He was homo publicus: a creature of the public sector and the state. And he was a realist.

Instead of ineffective, voluntaristic, private-sector oriented strategies like fossil fuel divestment, we need to demand industrial policy, planned transformation, led by government. Our own economic history shows that such a project is viable. The United States already executed a planned economic transformation once before, that was industrialization. The industrial revolution was not led by lone entrepreneurs operating in unregulated markets. Government was there at every turn, supporting, guiding, investing, procuring, subsidizing, but also penalizing and repressing with taxation, using carrots and sticks, to plan and drive forward an economic revolution to match the political one achieved by arms. We can look to that history for guidance and justification in the current struggle for a green reindustrialization.

By reaching back into American history and the story of a Founder, I am at least obliquely, making rightwing arguments for leftwing policies. The forgotten part of the Hamilton story shows us that an economically active government is not something new, it is not something exotic, not something foreign. Rather it is an organic and original part of American economic development. For the climate crisis, a planning state, an ambitious state, an interventionist state has to be at the center of the solution.