Dark Archives

Andre Bradley

Image Text Ithaca Press, $30 (boxed set)

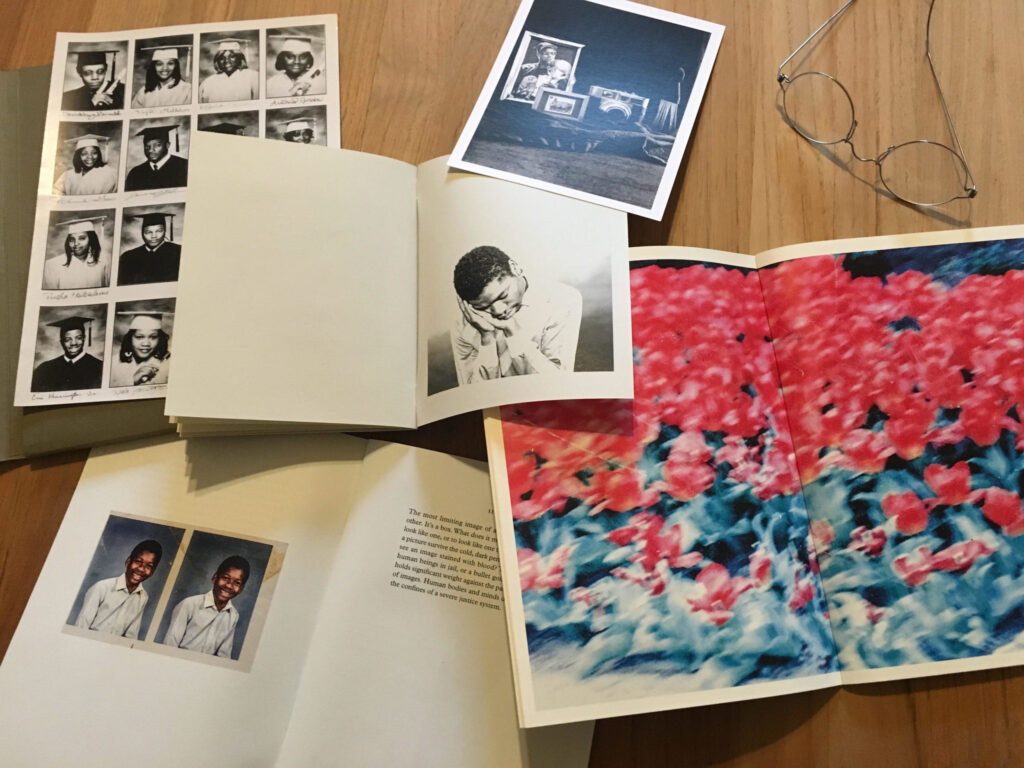

Dark Archives is not a book. A folder holds three small pamphlets of increasing length and size, without page numbers, each patch of prose numbered one through forty-one. Forty-one pages of uncaptioned photos accompany the words. “I was afraid of the dark,” Bradley writes, “but no book, or fact has given me the light needed to quell this fear.” He archives disparate features of this darkness in the prose and photographs—the space left by absence, the shadow of the unknown, the box of captivity, and American racial circumstance. “To me Black is quiet,” he writes, “Black is changing.” In the collection’s first photo, shot in black and white, light falls through trees upon an electric meter, a tarp covers a chainlink fence, and a drain pipe elbows across stucco, while shadows convey the action—their patterns strafe and shoot, blot, enclose and provide. Dark Archives moves by these methods, accompanying, framing, and articulating the fears of its speaker. One loose page carries the photographs of sixteen graduates, likely high school; on its reverse side appear sixteen headshots of young people, all thirty-two faces brown, all of them except one staring at the camera. Bradley’s speaker informs us, “I dropped out of school. I left to learn.” In light of this departure, Bradley collects intellectual, spiritual, material, and racial boxes—basements, backboards, rings for boxing, hoops for hooping. The light of the gaze he invites on these boxes does not defeat American circumstance so much as it empowers subjects—black subjects—to deal with darkness through a subtle, unnamed sense of mutual consequence. To hold Andre Bradley’s Dark Archives is to arrive at an extremely rare proximity to the force of such human consequence, an answer to certain of our needs made, as one suspects they must be made, as much of shadow as of light.

—Ed Pavlić

• • •

Every Day But Tuesday

Barbara Claire Freeman

Omnidawn, $17.95 (paper)

“Imagine,” Barbara Claire Freeman invites us, in her 2010 poetry volume Incivilities, “not having to apologize for the United States.” While she was clearly confronting the preceding “decade’s debacle”—a side effect of subprime doping, Dubya’s enabling fantasies, Citizens United, terror—circumstances have yet to outdate themselves. Her project in that debut, “to decline into the realities of the economy, / the lessons of capital,” serves as background music to her latest, Every Day But Tuesday (2015), which offers, sarcastically and presciently, “This country was nothing before it had a King.” The figures traversing Freeman’s obscure, elemental landscapes are colonists and captives, castaways and survivors, sovereigns and those who use the service entrance. They often stand on a shoreline, straddling “yes-in-motion” and “not ‘yes’ exactly,” or survey the American’t coast from a ship, as self and world are each halved, if not doubled—or exchanged. Indeed, giving is an important dynamic in Freeman’s proposal for a less privatized, more ethical polis, as is her frequent acknowledgment of its perverted forms—theft, mistrust, inequality, debt. The book’s medial section of 22 lyrics, loosely patterned after Dickinson’s poem 343 (“My Reward for Being, Was This”), takes a technological turn, whereby Freeman considers the lost, pirated, or otherwise compromised transmissions relayed by various communications media, from radio tower to copy machine, as indices of broader crises in personal and civic relations. Some poems stutter—staticky, cut out just short of making a sonnet or sense, their signal jammed—while others, like “Prequel” and “Sequel,” arrive in pairs, but minus a middle. As per its title, Freeman’s bracing book troubleshoots the broken circuit of time in our time, compelled by the precarious hope that our “present / soon-to-be outsourced” might nonetheless manufacture a worthy future here at home. Her nervous hum is “a song in the form of a question.”

—Andrew Zawacki

• • •

Some Say

Maureen N. McLane

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, $24 (cloth)

The first poem in Maureen N. McLane’s debut, This Carrying Life (2006), recalls “the day // I was thrown / from the imaginary car // & broke the barrier / of this carrying life.” Four books later, Some Say (2017) carries us back to an improbable vessel: “There is only so much / you can care for or carry // & for this there is / no one canoe.” “One Canoe,” to unsettle the point, is the poem’s title, verging on a claim. McLane earns it because of the idiosyncratic way her poems carry: their tonal leaps and unlikely continuities ingeniously defy the voice that says only so much. “Some songs accuse,” McLane writes, “Some forgive / Some just go.” This in a poem whose title (“Music Theory / Tuning”) is of two minds about whether it means to stay with us as an ars poetica. The poem is guarded in its intimations, sudden in its depths: “There was no way / to be without / a body & live.” In Some Say, the sun—a central presence, a “brute beautiful fact” the collection cannot quite make up its mind about—is a source of awe that simultaneously provokes more shadowed responses. A poem beginning, “As I was saying, the sun / is my enemy,” complicates this sense of comic exaggeration (“It burns the skin / years later the surgeon / cuts off”), carries other fates into its orbit (“O the women in childbirth / the soldiers”), then speeds to an encompassing close: a scar is “a medal / worn for all those / once in pain now dead.” Yet “in a blank cave / this our world,” a measure of exuberance sees McLane through, as in the bright distillation of Plato’s allegory where that line appears. Who else would call Socrates “the fabulous / sunstruck philosopher // who after all returned”?

—Tomas Unger

• • •

Rocket Fantastic

Gabrielle Calvocoressi

Persea Books, $25.95 (paper)

The first few lines of Rocket Fantastic bring the reader into an electrifying idiom: “I make my skin taut. I pull / my own neck back and to / the side. I come for myself.” By the end of the book, the reader finds herself dreaming in this idiom—in “whose” tongue. In the dozen or so “bandleader” poems that form the book’s erotic core, Calvocoressi uses the pronoun “whose” and the musical symbol dal segno (which directs a musician to segue “from the sign” to another place in the score) to “represent a confluence of genders in varying degrees.” Calvocoressi’s mind-bending third collection is a language immersion course in which the shifting rules of grammar and usage queer the notion of mastery. The tender syntax has a cutting edge, by turns halting and headlong. Wildlife in forms both human and nonhuman dance, chase, slam into, and soothe one another on a MacGyvered but watertight ark. Not since Ovid has the stag been so seductively rendered (“I saw whose arms and the taper of whose legs”), nor the glade so happily woven into everyday speech (“I kept going in deeper to the greenest / spot”). Calvocoressi’s joy in poetry is palpable, always embodied if also roving, with generous pockets of white space to give our shaky eyes places to rest. Moments of stillness open onto scenes from the poet’s distant past, where a troupe of recurrent figures (the Dad, the dowager, et alia) achieve iconic stature. Exacting lines accumulate; narratives spill over. By the book’s end the reader has borne witness to more lifetimes than she can track: “Which is to say: pure Decadence.” Calvocoressi vies with Maggie Nelson and Lidia Yuknavitch for the best sex on the page. Hélène Cixous (whose heroic constellation of works occupies the same corner of the night sky as Calvocoressi’s) once said “nos poèmes = nos peaux aiment,” playing on the fact that in French “our poems” sounds like “our skin loves.” This book strips life bare in language that tightens, flushes with desire, grows hot to the touch.

—Cassandra Cleghorn

• • •

The Missing Museum

Amy King

Tarpaulin Sky Press, $14 (paper)

The Missing Museum, Amy King’s fifth book of poetry, is both an exhibition and a dissection of feminine experience. In frenetic, often fragmented language, King examines family, romance, politics, conflict, and the insecurities therein. Employing a detached and at times clinical perspective, she succeeds in preserving the complexities of her subjects by admitting—sometimes extolling—confusion and ushering the reader toward the boundaries of their discomfort. Consequently, and to its credit, The Missing Museum is not an effortless read. From the outset the reader is introduced to frighteningly intimate territory; King’s voice, often elliptical, inconclusive, and sonically driven, demands consistent deliberation. The prologue is arresting, angry, and unprecedented: “Your mouth is full of noise and I live the anomaly. / That’s why I’m currently drinking. And making more / fuckworthy art. Because the rest is truly useless.” This passage prepares the reader for the onslaught of introspective cataloging to come, an appropriate aperitif for themes of distress—personal, political, and artistic—that pervade even the friendliest of King’s poems. Often this distress manifests as explicit contradiction: in “We Will Never Fully Recover,” the family she so earnestly declares as “not gay” inevitably “goes gay for all objects in contact.” King reflexively argues with herself, pitting fact against perception and questioning the essence of identity and experience. Though King’s sustained anger—an assertive and occasionally opaque voice—may initially overwhelm the reader, her candor facilitates a relationship of mutual respect and trust. Disparate visceral images persist long after the reader’s initial encounter. The Missing Museum, swollen with personal trauma and emotional experience, is innovative and novel: in King’s words, “Lend me your book when you / finish writing it. I’ll be the first to fill in its spaces.”

—Cassandra Balzer