I was born and grew up in Zimbabwe, and I voted first in the 2002 election. The people of my generation were all excited and thought that things were going to change. But Robert Mugabe was re-elected amidst claims of fraud and has been continuously re-elected. Nothing has changed. This Wednesday was election day in Zimbabwe, and Mugabe—despite claims of voter fraud from the opposition once again—appears to have secured another term in office.

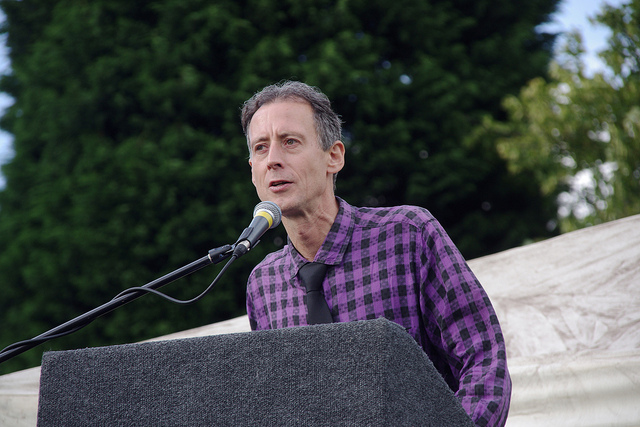

Peter Tatchell, a prominent LGBT activist, has put himself in harm’s way to fight a number of controversial causes, among them stopping Mugabe from committing crimes against the Zimbabwean people. The lanky Australian-born, British-based activist has tried to arrest Mugabe not once, but twice—in London in 1999 and in the lobby of the Hilton Hotel in Brussels in 2001—for crimes against humanity. On the second occasion, Mugabe’s Central Intelligence Operatives beat him badly and left him with permanent brain damage.

Tatchell has been beaten on more than 300 occasions, arrested more than 100 times, participated in over 3,000 protests and received more than 500 death threats. A live bullet has been sent through his letterbox, and his small south London flat—where I spoke with Tatchell—is frequently targeted by vandals.

Tinashe Mushakavanhu: In the 1980s were you one of the people who celebrated Robert Mugabe or whatever he supposedly represented?

Peter Tatchell: My association with Zimbabwe began way back in the early 1970s during the war of liberation when I was a young student. Like most Zimbabweans, I was opposed to the white minority regime of Ian Smith; the denial of votes to black people was unconscionable. Every attempt by a Zimbabwean nationalist leader to secure a peaceful negotiation of the transference of power to attain black majority rule was rebuffed. All the leaders ended up in prison or under detention or under house arrest, in fact, all kinds of restrictions were placed upon them infringing on their ability to campaign peacefully and non-violently for change. The end result was that many people concluded that the armed struggle was the only way forward. Although instinctively I am a pacifist and loathe violence, I felt that an armed struggle was the only option available to black Zimbabweans and somewhat reluctantly supported that struggle. As a young student I helped to fundraise to buy medical kits for guerrillas in the bush and for the civilian population in areas controlled by the liberation movement. At the time, Robert Mugabe seemed like a good guy. If you read the original program of ZANU-PF [The Mugabe-led Zimbabwean African National Union—Patriotic Front], it was a program for democracy, human rights, and social justice.

I wasn’t aware of all things that were going wrong, particularly the massacres in Matebeleland that really brought home to me the fact that Mugabe was betraying the very values and ideals that he once stood for. It became obvious that these were not actions by rogue military or intelligence personnel but systematic abuses perpetrated by the Zimbabwean army with the authorization and surely the knowledge of the Prime Minister. It was very clear that Mugabe was culpable and no action was taken by him to remedy those terrible abuses. He just looked the other way. A leader is supposed to protect the people, not sanction their abuse. The Matabeleland massacres were not an isolated incident. There were other, lesser abuses of human rights and there was a creeping drift towards authoritarianism indicated by the way in which Mugabe sidelined Joshua Nkomo; the way in which other opposition leaders, even people within ZANU-PF who dissented were quietly removed from office and sometimes suffered considerable abuse themselves.

In the late 1990s I was contacted by human rights activists in Zimbabwe who asked me to try and do something to highlight human rights abuses by the Mugabe regime. Initially I began by organizing some protests outside the Zimbabwe High Commission in London and we got a fair crowd supporting, got a little media coverage and didn’t really make an impact. And then in late 1999 I hit on the idea of using the power of citizen’s arrest to bring Mugabe to justice using the United Nations Convention against Torture 1984, which had been incorporated into British legislation as the 1988 Criminal Justice Act. Under this legislation, anybody who commits or condones acts of torture anywhere in the world can be arrested in Britain. So I thought this is a way in which we could at least highlight and draw international attention to Mugabe’s human rights abuses even if to get him arrested and put on trial might be quite difficult.

I ambushed his motorcade and actually had him under arrest.

Mushakavanhu: How do you feel about these attempts to bring Mugabe to justice, almost a decade later?

Tatchell: I am still astonished that no one else has tried in any other country to arrest and put Mugabe on trial. After all, if Slobodan Milošević can be indicted while he was the head of state of Yugoslavia, if Charles Taylor could be indicted while he was the President of Liberia, why not Mugabe? Torture and other human rights atrocities that have been perpetrated by the Mugabe regime are certainly crimes against humanity. So the case against Mugabe is incredibly strong. My question is why hasn’t the International Criminal Court acted? Why hasn’t any other private citizen in any of the other countries that Mugabe regularly visits tried to have him seized and put on trial? Why haven’t the national governments of the countries he has visited since enforce their own legislation against torture by arresting him? It shows a shameless dereliction of moral duty by so many people and of course the people who have suffered as a result of that hands-off approach are the people of Zimbabwe. They shouldn’t have to suffer in silence because of the inaction of so many western governments. These governments are hypocrites. They are complicit in one sense with the ongoing murder and mayhem that’s happening in Zimbabwe.

Mushakavanhu: Why then do you think you were not taken seriously by your own government when you tried to arrest Mugabe, despite the fact that you were acting within the boundaries of British and international law?

Tatchell: I was involved in two attempts to arrest Mugabe. The first attempt was in London in 1999 when three colleagues and I ambushed his motorcade and actually had him under arrest. But when we explained this to the police, we were arrested and Mugabe was given a police escort to go Christmas shopping at Harrods. This was despite the fact that we had very strong evidence; we had affidavits and information from Amnesty International about the torture of two journalists, Ray Choto and Mark Chavunduka from The Standard newspaper in Harare. We had the evidence that Mugabe had in effect sanctioned, authorized and approved their torture. He boasted of it afterwards saying they were lucky they didn’t suffer even worse. And so the legal case against him was very compelling, which made the reaction of the police all the more shocking. I don’t believe that decision to let him go was made simply by officers at Belgravia Police Station where we were taken. I believe that it was almost certainly made with the approval of the then-Police Commissioner, Sir Paul Don, the then Attorney General Lord [Peter] Goldsmith and the then-Foreign Secretary Robin Cook. I should think that all of these people were consulted about this case.

When I look back and think to myself what if— what if he had been arrested and put on trial in 1999— that was before the real mayhem and murder began in Zimbabwe. It would have taken out of the picture the man responsible for this orchestrated campaign of violence and terrorization and intimidation. I am not saying that having got rid of Mugabe or put him on trial like Milošević in The Hague or in a British court would have made things perfect. I doubt it. There are other people in ZANU-PF who are also culpable and share the same oppressive tyrannical agenda. But I think with Mugabe out of the way the scale of human rights abuses probably would have been less. In fact, the regime would have been destablized, there would have been a power struggle within ZANU-PF and things may have completely unraveled. So to me that makes it even more shocking that the British police and government allowed him to go back to Zimbabwe. They allowed him to go back and escalate the regime of terror.

The second attempt was in Brussels in 2001 when I ambushed Mugabe in the lobby of the Hilton Hotel. Again I was acting not only with the accordance of the United Nations Convention against Torture but also acting within Belgian law, which incorporates the convention into its domestic legislation. So the legal basis for Mugabe’s arrest in Brussels was overwhelming, yet Belgium, a signatory to the UN Convention against Torture, decided to look the other way and again allowed Mugabe to get away with it. The terror campaign was in full-swing and backed by the war veterans. If Mugabe had been arrested in Belgium in 2001 as he should have been in accordance with Belgian and International human rights law, I think the course of Zimbabwean history might have been different.

I think all of us are aware that although the level of violence and intimidation is not as extreme as a decade ago, it is still ongoing. There are still arrests, detentions without trial, torture and other human rights abuses. I find it shocking the way in which the international community has largely become blasé and matter-of-fact. Mugabe is still there. He is perhaps not quite as powerful as he once was. The power-sharing agreement, for its limitations and flaws, has to some extent limited his room for maneuver but he is there based on a fraudulent presidential election. The downside is that the opposition does not have the representation in parliament they deserve.

Mushakavanhu: When you look back and reflect on that first attempt to arrest Robert Mugabe, do you ever feel vindicated that you brought him into the international limelight just before everything unraveled in Zimbabwe?

Tatchell: The media coverage of that first attempt at citizen’s arrest did help expose and shine a light on human rights abuses that were happening in Zimbabwe. But I also feel a sense of disappointment and sadness because it didn’t succeed. So in that sense I am of two minds and I wish I had succeeded, because the history of Zimbabwe might have been very different. Who knows, we can only speculate. And I do feel very angry towards the Labour government [of Tony Blair] because it was the Labour government at the time who allowed Mugabe to go back to Zimbabwe to continue his murder and mayhem.

The last blow knocked me unconscious. It has left me with permanent brain and eye damage.

Mushakavanhu: Moving on to the second attempt, which resulted in your being badly beaten by his bodyguards. Did you ever consider stopping your campaign for human rights after those very damaging moments?

Tatchell: I knew there was risk. I knew there were dangers. But I hoped that in broad daylight in London or Brussels they wouldn’t dare shoot me, particularly if there TV cameras and journalists around. But that was a big gamble. They could have fired at me. Who knows? But I felt so strongly that something had to be done to highlight the human rights abuses that were happening in Zimbabwe. The intervention needed something dramatic and that’s why I hit on the idea of a citizen’s arrest, something that would hit the news headlines and make the world know and discuss or perhaps act against Mugabe’s tyranny. I never wanted to be beaten up. The beating in Brussels was pretty severe. The last blow knocked me unconscious. It has left me with permanent brain and eye damage. I never wanted that. I feel regretful that that happened, but I don’t feel regretful about doing what I did because it was my moral duty to do what I can to help highlight and if possible stop the oppression of the people of Zimbabwe.

I think the consequences would have been much worse in Zimbabwe. I don’t see myself as particularly brave or heroic. Bravery, courage, heroism— those are words that I reserve for the people of Zimbabwe who really are taking and have taken extraordinary personal risks and have paid with the loss of their own personal liberty, and indeed sometimes with the loss of their own lives. Those are the real heroes. What I did was very modest and insignificant by comparison.

The arrests did make a lot of people think: Why is this being left to this rather skinny man from London to try and put Mugabe on trial? [laughs] Why aren’t governments doing something to bring him to justice?

Mushakavanhu: Mugabe uses a lot of homophobic language, addressing many who speak against his regime with gay slurs. What is your reaction to that?

Tatchell: In response to the citizen’s arrest Mugabe blasted me as a “gay gangster” and I wear that badge with pride. [laughs] I am glad that I got to him. I remember when I had him under arrest in London, he was in the car and I was holding his arm. You should have seen the look on his face. His eyes popped and his jaw dropped. An ashen color came across his face. I think he thought he was going to be killed. My response was “no, we’re not going to kill you. We’re going to take you to a court of law and put you on trial. I am glad you now know how your victims feel, the victims in those torture chambers manned by your infamous CIO [Central Intelligence Organization]. We are not going to murder you, but we will put you on trial.”

I would be very interested to hear what a psychiatrist has to say about Mugabe’s obsession with homosexuality. Given all of Zimbabwe’s problems, given the dire state of the economy, the suffering of its people, why is he so obsessed with homosexuality? It’s not natural. It’s not normal for any man to be so obsessed with other men. What is it in his own mentality or his own sexuality that drives him to this obsession? There are theories, research by Professor Henry Adams at the University of Georgia, which found that 80 percent of strongly homophobic heterosexual men have deep insecurities about their own heterosexuality and in many cases are repressed self-loathing homosexuals. I don’t know whether that’s true of Mugabe but I do know his obsession with homosexuality is very strong and weird.

He apparently thinks that by going on these tirades against homosexuality he is somehow proving his masculinity; he is somehow hitting his critics below the belt. But I think people see him as a man with a very weird obsession with same-sex relationships.

Mugabe often says that homosexuality is un-African. If you go back in history to the period before colonization in many parts of Africa, homosexuality was sometimes accepted. It was seen as part of the fabric of traditional African society and in some African cultures homosexual men were even venerated and given ritualized roles within tribal societies. What is un-African is the vicious homophobia that Mugabe propogates. Homophobia was imported largely by the Europeans who came to colonize Africa. Zimbabwe’s anti-gay laws were not invented or enacted by the black Zimbabwean peoples; they were imposed by the British colonial administration in the nineteenth century. When the first explorers and colonizers came to Zimbabwe and other African countries many of them were horrified by the existence of homosexuality among indigenous peoples and argued that this justified colonialism; the Christian missionaries had the same view. They said, “look, these people are savages, they are barbaric, they indulge in homosexual practices and no one condemns them, this is why we must come here and make them Christian and put them under British rule.” Mugabe has internalized all that imported homophobia. He has internalized it so well that he has apparently convinced himself that these ideas didn’t come from the British colonizers or the Christian missionaries but actually came from Africa. That’s nonsense.

Mushakavanhu: What is your message to an ordinary Zimbabwean facing another five years with him as president and leader?

Tatchell: My message to the people in Zimbabwe is I understand your pain and suffering. I feel for what you have been through. It’s wrong, the ways you have been let down so badly by the international community, but please don’t lose hope. Freedom and justice have been a long time coming. No tyranny lasts forever. The Nazis promised a thousand-year rule. They lasted only twelve years. Mugabe has lasted longer but he too will have his fall. You will be free. You will have a democratic Zimbabwe. Human rights will be respected. Hang on in there. Don’t give up. Your heroism is amazing. I salute you.

Photography: Matt Buck/flickr