Sweet Sixteen

Directed by Ken Loach

Lions Gate Films

Raising Victor Vargas

Directed by Peter Sollett

Samuel Goldwyn Films/Fireworks Pictures

8 Is realism the mission of film? André Bazin thought so. Bazin was a French film critic who, in the decade after World War II, cofounded the film magazine Cahiers du Cinema and made film studies a respectable academic discipline in France before dying of leukemia at age 40. Trained as a philosopher in Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, he thought that the motion-picture camera could be a purifying device, able to provide a God’s-eye view of the world without the intervening vanity and artifice of human consciousness. Bazin was by all accounts a saintly man, and his own benignity surely informed his understanding of film and what he saw as its realist mission.

The premise of sacred realism disciplined Bazin’s aesthetic sensibility. He criticized German expressionism: the play of light and shadow obscured reality. He was also critical of Eisenstein’s montage: the rapid juxtaposition of two different images to convey a third was, he felt, artistic posturing. In the films of the French filmmaker Eric Rohmer, a colleague of Bazin, one can still see his influences. But Bazin understood that realism was not just a matter of how the director filmed and edited, nor was he doctrinaire. My own impression is that he admired films with moral ambition. So, like many of his fellow critics at Cahiers du Cinema, he found much to fault in Hollywood’s studio-controlled productions, although he liked Chaplin and Welles.

Bazin was an early enthusiast of Italian neorealism, which had many of the qualities he prized most: the cinematography was almost documentary in style; it was shot in the streets; the actors were often untrained; and the grim reality was leavened by a redemptive humanism. One of Bazin’s favorite films was Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief. Made entirely with untrained actors, and by general consent one of the greatest films ever made, it tells the story of a poor man whose only means of support is his bicycle. He rides around Rome putting up Hollywood posters, thereby earning enough income to feed his family. When his bicycle is stolen he is desperate. His search for it with his small son is a searing depiction of poverty in post–World War II Rome. The police, the church, and the labor union offer no help, and the relationship between father and son becomes the emotional center of the film. The father gives up in despair and then, by a miraculous stroke of luck, he spots the bicycle thief and pursues him into a brothel. The police are called but it is one man’s word against another’s. In the sad and inevitable ending, the poor man decides to steal a bicycle as his son looks on in disbelief. When the father is caught and later released by the police, his son forgives him and the two are lost in a crowd.

The screenplay for The Bicycle Thief was written by a Marxist, but unlike other neorealist films there is no Christian-Marxist resolution. Doctrinaire Marxists criticized it, but Bazin declared it the only true Communist film of the decade.

• • •

In opposition to Hollywood’s increasingly unreal and commercial escapism, independent filmmakers all over the world have been reinventing their own versions of realism. No matter how grim or perverse these new realists have become, most of them share Bazin’s sense of the mission of film. If they are not looking for God, they are at least looking for something that does not idealize the human condition but redeems it.

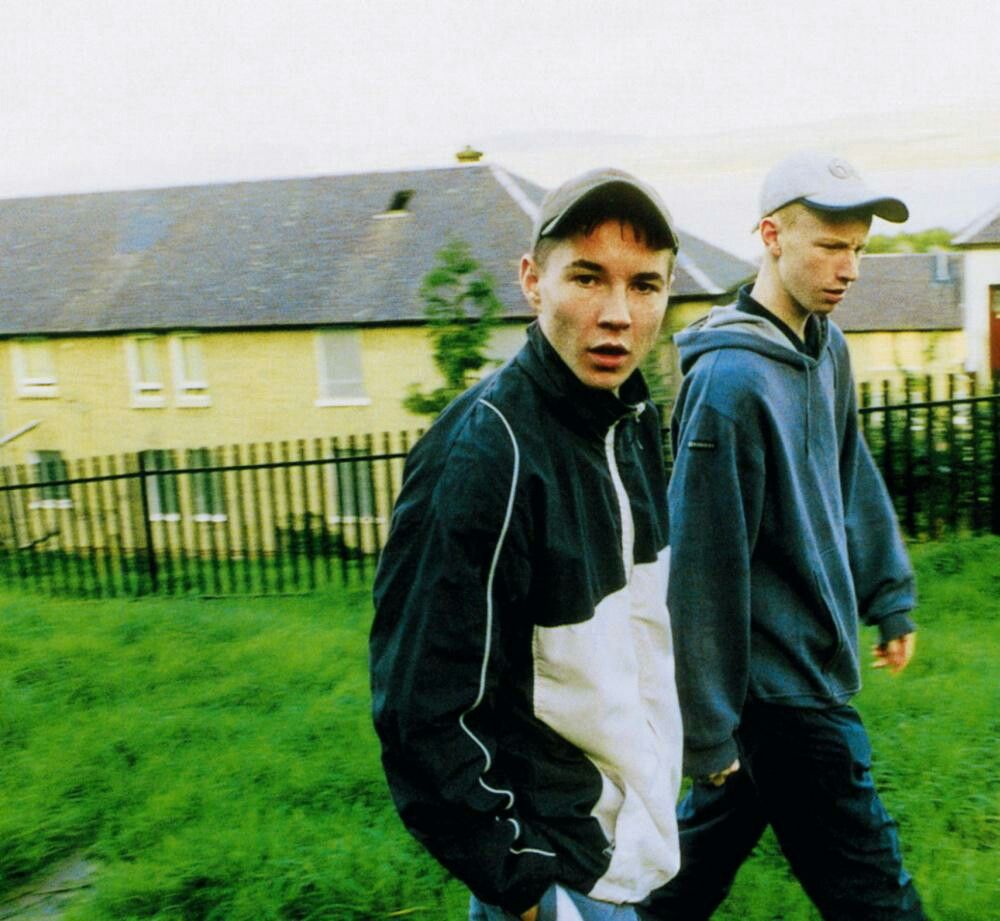

Bazin and The Bicycle Thief came particularly to mind as I reflected on two small-budget independent films of the summer, both of which left a lasting impression—British filmmaker Ken Loach’s Sweet Sixteen and Peter Sollett’s Raising Victor Vargas,the first feature-length film by the young New Yorker. Both films are about teenage boys coming of age in lives and circumstances that promise only dead ends. Both used Italian neorealist methods: they are almost documentary in style, shot in the streets, and made with untrained actors. But they present fundamentally different visions of reality: one is a tragedy, the other a comedy.

Ken Loach has long championed social realism, and his characters are bottom-of-the-barrel Britons who dream of something better. His most memorable film, Kes, is about a deprived and blighted teenager whose formal education is a failure. When he finds and adopts an injured kestrel, however, he embarks on a project that redeems his life. Loach is morally purposeful. After studying law at Oxford, he decided he could accomplish more as a filmmaker than as a lawyer. In the ‘sixties he made a BBC documentary about a homeless, mentally ill woman that is said to have changed public policy in Britain. Several of his films are simply unforgettable, and all of them make clear his left-leaning politics.

What Vittorio De Sica said about himself applies equally to Loach: his films are a “monument to the possibility of human solidarity.” And Sweet Sixteen is Loach at his best, depicting the life of a teenager in Greenock, Scotland, a city built along the River Clyde outside Glasgow. Once home to a thriving shipbuilding industry, Greenock now has the dole and drugs. Loach and his writer, Paul Laverty, spent months around Glasgow talking to young people and developing the story they would film.

Teenage speech in Greenock includes the F-word as verb, adjective, adverb, or expletive in almost every sentence. Loach faithfully reproduces their language. Liam, the 15-year-old protagonist of Sweet Sixteen, speaks with such a pronounced burr that what one hears is “fecking.” Because the characters speak with accents incomprehensible to American ears, Sweet Sixteen(like other Loach films) has running subtitles, so the audience gets both auditory and visual doses of the F-word. The language was too much for the British Film Board, which gave Sweet Sixteen an age-18 rating. Loach was understandably outraged, because the rating means that teenagers, for whom profanity has become a peer-group requirement, will not be admitted to the British theaters that show the film.

Loach’s version of realism opens on a brilliantly starlit night-sky. Liam (Martin Compston) and his best friend Pinball (William Ruane) are charging young children a few pennies to look through Liam’s cheap telescope at one of the planets. Loach’s poor may be downtrodden, but given a chance they will still reach for the stars. Most of the poor in Greenock will, however, succumb to the lure of drugs, to the pint, and to lives without meaning or direction. Liam’s own mother (Michelle Coulter, a drug counselor in real life) is an addict serving time in prison because she has taken the rap for Stan, Liam’s stepfather (Gary McCormack), a small-time drug dealer. Liam hates Stan, and he dreams of making enough money to take his mother away from Stan and his drugs to a home of her own in a better section of Greenock.

When Loach and Laverty were researching Sweet Sixteen and talking to young people around Glasgow, they were struck by the attachment of teenagers like Liam to their mothers. In Sweet Sixteen Loach presents that attachment as a Greek tragedy of blind love. Liam is determined to rescue his mother and will do anything to raise the money—including selling stolen cigarettes and charging children to look through his telescope. But Stan has his own schemes. He takes Liam to visit his mother in prison, where Liam is to put a large wad of drugs in his mouth and pass it to her in a kiss so she can sell the drugs to other inmates. Stan creates a distraction to permit the pass-off, but the rebellious Liam refuses to go along with the plan. His stepfather savagely beats him, breaks his telescope, and throws him out of the house. Liam, brave and resourceful, sets out to make money the only way he can: he and Pinball become drug dealers by stealing Stan’s stash and selling it at bargain prices.

Made with untrained actors, the film has home-video moments of self-conscious awkwardness. Liam is played, however, by a lean and wiry young man who lives the part. He does not look or move like an actor, but he is entirely convincing. His skill and courage as a drug dealer bring him to the attention of the serious players in Greenock. They take him into the big time but they up the ante: he has to prove he is willing to kill, and to betray Pinball. Loach’s storyline saves Liam from sociopathic callousness. His willingness to kill is a test that he is not required to complete. And Pinball, who has madness in his eyes from the start, knows he has been betrayed. He confronts Liam, slashes his own face to Liam’s horror and disappears from the movie.

Like the father in The Bicycle Thief, Liam has become a criminal for reasons that demand our forgiveness: he has done it all to save his mother. On the day she gets out of jail, Liam, now rolling in money, takes her to a posh apartment in the best part of town and gives her the keys. But the next morning she is back with Stan, his drugs, and his abuse. Liam follows her, and when Stan mocks him there is a brawl. Liam stabs his stepfather, completing the Greek tragedy. His mother could not be saved and now, on his 16th birthday, neither can Liam.

Although the F-word is everywhere in Sweet Sixteen, sex is nowhere in Loach’s version of realism. Liam is completely chaste, surely an unnatural state for a teenage male in the real world. But Loach is determined to preserve his hero’s childlike innocence. Liam may be acting like an adult criminal, but in his pure and blind love for his mother he remains a child. That love both redeems his character and leads to his destruction.

• • •

Realism has many guises in cinema, but if it is to succeed, the audience must believe it has witnessed something authentic. Critics came away from Raising Victor Vargas feeling they had learned something authentic about the Hispanic Lower East Side of New York. Ironically, Peter Sollett set out to make a fairly autobiographical film about his teenage years growing up in his Jewish-Italian neighborhood in Brooklyn. It turned into Victor Vargas, he explains, because the best of the would-be actors who responded to his ads were Latino.

Like the man who played the father in The Bicycle Thief—whom De Sica asked to go back to his previous work when the film was completed—Sollet’s featured performers were not professional actors, although they may aspire to be. Raising Victor Vargas is a collaborative effort. Most of the lines and the themes for the story were created in workshops in which the actors participated.

What emerged on this side of the Atlantic was sex. Indeed,Raising Victor Vargas is almost entirely about sex, but it too is in search of redemptive innocence. Victor (Victor Rasuk) and his friends in the Lower East Side use the F-word and the N-word freely, and attractive teenage females like Judy Marte are confronted with truly repulsive streams of obscenities meant as menacing declarations of sexual interest. If Liam’s project was saving his mother, Victor’s project is having sex with girls like Judy (both use their real first names in the movie).

Sollett’s film opens in a Lower East Side project in broad daylight. Victor’s best friend is standing outside screaming for Victor, who puts his head out of the wrong apartment window and unwittingly reveals that he has been having sex with Fat Donna. This dalliance will ruin his reputation in the neighborhood.Raising Victor Vargas is the story of how Victor regains his honor. He sets out to seduce Judy, the most attractive young woman in sight. As in Sweet Sixteen, there are no visible fathers, no schools, no jobs, not even drug dealing. Victor, it seems, has nothing to do except to pursue Judy. He is not into drugs, not into crime, and not into violence: he is nothing but a horndog who tries to charm young women, not menace them.

His campaign to retrieve his macho reputation begins at a crowded public swimming pool, where Victor and best friend Harold (Kevin Rivera) notice Judy and her best friend Melonie (Melonie Diaz) sunning themselves. Looking to prove himself, he approaches Judy with Harold in tow and tries out his best pick-up lines. He gets a cool reception, but Harold connects with Melonie.

Victor’s façade of adult sophistication is easy to see through, but Judy is more complicated. A beautiful young woman, she is the constant object of crude sexual intimidation. She is, in fact, a virgin doing a high-wire act of self-preservation in a culture in which pressures to perform sexually often precede puberty. Judy decides she can use Victor as a boyfriend she can control to ward off those she cannot. Along the way Sollett reminds us that these teenagers are children. When Melonie succumbs to Harold and takes off her clothes, she giggles about the ducks on her underpants and he giggles, too. Victor’s younger sister uses the F-word, but we see her sleeping with her teddy bear.

The film is also about Victor’s makeshift family. Victor, his brother (played by Rasuk’s real brother), and their sister by a different father are cared for by their grandmother (Altagracia Guzman). The three children share a bedroom and there is no privacy. This makes things difficult for the younger brother, who is his grandmother’s sainted favorite and who is constantly in the bathroom masturbating. When his grandmother catches him, she blames Victor the horndog’s influence and tries to have the authorities remove him from the apartment. Ms. Guzman, in real life a seamstress and a clothes designer, balked at this turn in the story line, which she declared to be contrary to her nature. Sollett convinced her that it was necessary for the film: it creates the family crisis that must be resolved. When she cannot get rid of Victor, she lectures her grandchildren, telling them to remember that she is the only one they have. In the most telling line in the movie, Victor stands up to his grandmother and tells her, “No, Grandma, we are the only ones you have.” Of course they both are right, and at this moment all of them appreciate what families in crisis often forget.

Victor’s statement to his grandmother reveals a sense of self-respect and self-acceptance behind the horndog identity. He is neither ashamed of himself nor resentful of his circumstances. When he realizes that Judy is using him and even laughing at him, he is neither enraged nor menacing. Instead, he simply acknowledges who and what he is. The real Victor wins Judy’s trust and more. She puts aside her façade of sophistication, acknowledges her innocence, and instead of sexual struggle and surrender, there is a redeeming moment of human intimacy.

While Loach’s Sweet Sixteen is tragic, Sollett’s realism is a comedy with a happy ending that affirms the possibility of human connection. And Raising Victor Vargas reminds us that sex, no matter how much our culture degrades, profanes, and commercializes it, can be redemptive. I think that Bazin and De Sica might have approved of both of these films.