If I were a Hollywood actor, I would be calling my agent to be on the lookout for roles in which I could play a mentally troubled character. Kathy Bates earned her Oscar playing a madwoman in Misery in 1990; the next year, Anthony Hopkins earned one for the role of cannibal Hannibal Lecter; in 1993 Holly Hunter was the mute heroine of The Piano; 1994 produced Tom Hanks as the strange but winning Forrest Gump; in 1995 there was the alcoholic Nicholas Cage of Leaving Las Vegas; Geoffrey Rush won the Best Actor award for his 1996 performance as schizoaffective pianist David Helfgott; 1997 was Jack Nicholson's turn for doing obsessive compulsive disorder; James Coburn picked up his Oscar as the sadistic paranoid father in 1998'sAffliction; and in 1999, Michael Caine was a narcotics addict and Angelina Jolie co-starred as the sociopath of Girl, Interrupted. That's ten Oscars in ten years and I am not counting the borderline cases like Jessica Lange who is half mad in most of her movies and has already collected two Oscars.

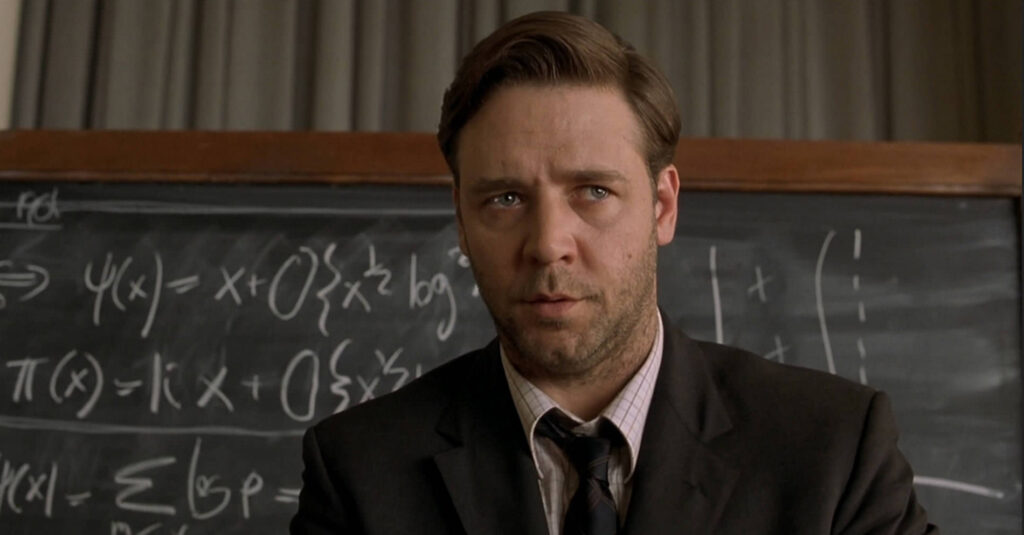

This year there were four nominations for portrayals of mental illness: Russell Crowe's schizophrenia, Judy Dench's Alzheimer's, Sean Penn's mental retardation, and Ben Kingsley's psychopath. Just to be nominated is a career boost and according to a respectable Canadian Medical study, winning adds almost four years to an actor's life. Russell Crowe was awarded Best Actor for Gladiator last year and was a contender this year for his portrayal of John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. Although Crowe did not win a second Oscar, director Ron Howard attributed the film's Best Picture honors to Crowe's extraordinary artistry and dedication.

Do we overestimate the accomplishments of actors in these roles? Perhaps, I thought, as I watched A Beautiful Mind a second time. If the task was to portray the tortured self-concerns that plague real people who suffer from schizophrenic disorder, Crowe's acting fails. It may be Akiva Goldsman's script. Goldsman's previous credits include Lost in Space, Batman and Robin, and Batman Forever. His screenplay takes a page out of Sylvester Stallone's book, and makes Nash's story into theRocky-style, romantic triumph-over-adversity version of mental illness. Nash's demons have become imaginary playmates and the awful darkness of his many years of severe mental illness is barely visible. Crowe plays the Hollywood versions of genius and schizophrenia, and his own charm and screen personality win over the audience. Crowe's face now appears on the cover of Sylvia Nasar's award-winning biography of Nash. Hollywood has appropriated Nash's identity.

• • •

The real John Nash does have an extraordinary story. He recovered from paranoid schizophrenic disorder and achieved the intellectual equivalent of a Heavyweight Championship—a 1994 Nobel Prize in Economics—for work that originally appeared in a Ph.D. thesis he completed in 1950 as a twenty-year-old graduate student in the Princeton mathematics department. Nash won his Nobel Prize for work in game theory, the mathematical study of interactions among rational individuals, where each person is trying to do the best for him or herself, and the fate of each depends on the conduct of others. Nash focused on what are called "noncooperative games": interactions among individuals who cannot make enforceable agreements. He introduced a concept—now known as "Nash equilibrium"—to predict what happens when rational individuals play such games; and he showed that, in a very wide class of non-cooperative games, there exists a Nash equilibrium, in which no one has any incentive to change strategy. Nash's contribution was a large advance over the work of John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, whose 1944 treatise on The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior had provided a clear solution to the puzzles of rational interaction only for the special case of zero-sum games, where one person's gain is another person's loss. Though game theory fell out of fashion in social science not long after Nash finished his thesis, it experienced an extraordinary resurgence in economics in the 1980s. And in 1994, the Swedish Academy decided to issue a "game theory prize" to Nash, John Harsanyi, and Reinhold Selten.

The movie, perhaps thankfully, stays away from Nash's ideas. The closest thing to an explanation of Nash's intellectual contribution comes in a bar scene in which Nash explains to his fellow graduate students that they should not all focus their attention on the same beautiful blond—that's a zero-sum game, with only one winner—but should each pair up with one of her friends—a positive-sum game, with potential gains all around. That misses the essence of Nash's contribution, which was about social interaction among rational individuals who are not coordinating their conduct. But that's Hollywood.

Instead, the movie depiction of Nash's life plays (with some success) on the same feel-good, tearjerker emotions as Stallone's movies did. But unlike Rocky, the distortions and misrepresentations in A Beautiful Mind have troubling implications.

Geoffrey Rush—like Crowe, an Australian—won his Best Actor Oscar as a concert pianist who recovers from madness in Shine. That film perpetuated two of the most guilt-inspiring myths about serious mental illness. The first, devised by American psychoanalysts (Freud certainly knew better), is that bad parents cause the serious mental illnesses of their children; one of my medical school professors invented the term "schizophrenogenic" for such parents. The second more insidious myth is that love is the cure. The love-cure idea is guilt-inspiring because it makes those involved in trying to help a child, a spouse, a parent, or a patient with a serious mental disorder feel personally responsible when their efforts fail, personally responsible because of their inability to offer unconditional love.

All myths contain a kernel of reality. Parents do pass on their genes to their biological children and genes do contribute to serious mental disorders. And although "love is not enough" you have a better chance of making it if someone cares about you. Shine portrayed both fulsome myths. The promising concert pianist David Helfgott is driven into schizoaffective disorder by his authoritarian Jewish father who then abandons him (a total misrepresentation according to his brother and sister). He is rescued from madness by a gentile woman who is capable of unconditional, or in her case, holistic love. The movie made the real David Helfgott an international celebrity. Loved and managed by his wife without psychiatric medications, he made it all the way back to the concert circuit where audiences packed the halls to give him standing ovations. Although she does not want for critics, his wife has in fact been his sustaining force. Helfgott is still attracting audiences in Japan, Singapore, and South Africa even though the judgment of musicians is that his piano performances can be as embarrassing as Stallone's boxing. The miracle is not in the virtuosity of his music but in the triumph of the human spirit.

A Beautiful Mind spares us the myth of parents causing their child's schizophrenic disorder and as a result some mental health professionals have viewed it as a kind of progress. In a New York Times interview, psychoanalyst Glen Gabbard asserted that A Beautiful Mind was "one of the better portrayals, if not the best" of schizophrenia in film. But he seems to have been emphasizing the Rocky factor—that this film found a way to help audiences empathize with a man who suffered from and overcame the most serious form of mental disorder.

Schizophrenia is experienced as a drama of the self that takes place on the stage of one's own mind. The person is trapped in an egocentric and often terrifying reality. At its worst, nothing else matters, meaningful communication ends, the self is unavailable to others and the person becomes a burden and an outcast. There have been films that denied the torment of this terrible illness by romanticizing it as a form of wisdom or special insight. A Beautiful Mind demonstrates how schizophrenia is in fact the nemesis of genius.

In order to make Nash sympathetic, the director, Ron Howard, had to do away with many of the disturbing incidents—particularly Nash's stunningly selfish, egocentric, and cruel behaviors—described in Sylvia Nasar's biography. In the black and white of the Rocky genre, the hero must have an innocent soul. In Shine, David Helfgott's first marriage was eliminated from his story; similarly, Goldsman omitted Nash's five-year relationship with Eleanor Stier, the woman with whom he fathered his first son. The stingy and selfish Nash refused to acknowledge his son and would not provide child support until Stier sued him. Also censored were what Nash described as his homosexual "experiments," as well as the fact that he was arrested for soliciting in a public toilet and, as a consequence, lost his security clearance.

The real Nash, it must be said, was "as handsome as a movie star," enormously appealing to men as well as women, and he was apparently attracted to both. Russell Crowe is actually not as good looking as the young John Nash. There are two slightly bewildering scenes in the movie where, on first meeting, young women choose the distracted Nash over his friends: the scenes seem less contrived after you see the Nasar biography photograph of the young John Nash in his bathing suit. But the ugliness of the real Nash's political and religious extremism, his snobbery and anti-Semitism, and his sheer interpersonal nastiness had to be censored to make him an innocent soul. Moreover, in the film Nash focuses his paranoia on the Soviet Union, whereas the real Nash was not a Cold War patriot, but kept trying to relinquish his American citizenship and was willing to work for the Soviet Union. All of these more disturbing facts and worse became part of gossip that attended Oscar voting on the film. By a perverse logic, some members of the Academy wanted to vote on the real Nash instead of the character in A Beautiful Mind.

• • •

The most compelling statement about John Nash's psychotic break with reality can be found on the first page of Nasar's biography. He is visited at McLean Hospital by a Harvard mathematics professor who asks, "…how could you, a mathematician, a man devoted to reason and logical proof…how could you believe that you are being recruited by aliens from outer space to save the world?" Nash supposedly gave this reply: "Because…the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously."

My own guess is that if Nash gave this striking answer he was not being entirely truthful. Like many of the best mathematicians Nash had an unusual inwardness which goes along with the ability to sustain concentration at the highest level. But other mathematicians agree that Nash also had a kind of unique intuition in his approach to solving problems. So perhaps that intuitive sense is what he meant when he said that the ideas came in the "same way." The film tries to convey this "same way" by presenting images of Nash perceiving patterns. But what first troubled Nash was much more typical of patients who develop schizophrenia: he had "ideas of reference." As Nash developed schizophrenia, he noticed men wearing red ties, he began to believe that red had a special significance, and that the significance had particular reference to him: the patterns located him at the center of a new reality. So, too, the real Nash would notice words and phrases in The New York Times and put them together in ways that proved to him "supernatural beings" were placing those messages in the newspaper for him. And although his biography is far from clear about the sequence, he has revealed, if only in retrospect, that he was hearing voices. These are all common early symptoms of the onset of schizophrenia. Nash seems to have become psychotic in a very typical way: his brain began to play games with his mind. It is virtually impossible not to trust your own mind and brain; that is why the basic problem of serious mental disorder is that the patient has no "insight." Nash could not disbelieve his own mind, not even a genius can do that.

The drama of the self in Nash's case apparently began with grandiosity at a time when he was struggling to gain tenure in the MIT mathematics department, his wife was pregnant, and he was already thirty—old for an ambitious mathematician. In the midst of all these personal stresses, aliens were calling on him to save the world. He refused the offer of a prestigious professorship at the University of Chicago, stating in his letter that he was about to become the "Emperor of Antarctica." He was the "left Foot of God on Earth." And of course when he shared the story of the drama that was unfolding in his own mind everyone thought he was insane. Most psychiatrists would agree, at least in retrospect, that Nash had a genetic mental disorder. His legitimate son, John David Nash, is a math whiz who, sad to say, has a similar psychosis.

Like the visiting Harvard mathematician, Nash believed in reason and logical proof, and in his biography he claims to have reasoned his way out of his delusions. He also says that it was like dieting, in that he did not allow himself to think about religious or political matters. Nasar quotes him, "I emerged from irrational thinking ultimately without medicine other than the natural hormonal changes of aging." So Nash the math genius as well as Helfgott the concert pianist deny that they were helped by medication. (A Beautiful Mind actually undermines this claim and that is an important matter to which I return below.)

Psychiatrists who have done careful research on the long-term outcome of schizophrenia find that a small percentage of those who suffer from the disease do recover. But some researchers have begun to wonder whether we have for a century wrongly believed that "schizophrenia" is really a single disorder. Nash, who was blessed in many respects—his genius, his looks, his friends who cared about him— was perhaps also fortunate to have a variant of schizophrenic disorder that can be overcome. It should be said, however, that Nash is not as enthusiastic about his "recovery" as is the rest of the world. After his early mathematical work was recognized and he had won the Nobel Prize for Economics, he was invited to the World Psychiatric Association in Madrid to speak. He used that opportunity to compare himself to an artist who has recovered but can no longer paint.

Sylvia Nasar's biography is superb at recreating Nash's social reality and providing the ordinary reader with some understanding of the mathematical problems that interested Nash and of the intellectual contributions honored by the Nobel Prize. He, however, took the position of "Swiss neutrality" to her project, and we do not get any detailed account of the megalomaniac drama going on inside his head. That drama was to be the subject of the film and it is entirely an act of the screenwriter's imagination.

• • •

All films turn life into melodrama. One can say that about Citizen Caneas well as Rocky, Shine, and A Beautiful Mind. The filmmakers were quite ingenious in imposing the needs of the medium on their depiction of Nash. The first imaginative leap was to transform Nash's voices and obsessions into visual hallucinations. And the screenplay puts them into Nash's twenty-year-old mind on his first day as a graduate student at Princeton. He is already mad when the film begins, but Ron Howard makes the viewer believe that the hallucinations are real. Nash's Princeton roommate (Paul Bettany) shows up; he is an appealing, attractive man, an expert on D. H. Lawrence, and he becomes the emotional mainstay of Nash's existence. Later, at MIT, the roommate reenters Nash's life with a young niece (Vivien Cardone) and she, too, emotionally sustains the troubled genius. Halfway through the movie, and ten years later, we learn that both are unreal. By then, we are as attached to these benign hallucinations as Nash is. We too want them to be real and now we are inside the drama of the self along with Nash and we have to struggle to reconstruct our own sense of reality. That is enough of an achievement for this film to garner my Oscar vote.

Though visual hallucinations do not suggest schizophrenia but indicate other acute and toxic illnesses, the cinematic device provides a vivid and useful experience. These imaginary playmates, which are what they most resemble, turn nasty. They join forces with an imaginary CIA agent (Ed Harris) who enlists Nash's aid to decode Soviet messages hidden in such periodicals as Time and Life. Instead of communicating with aliens, the fictional Nash is crazed but patriotically fighting the Cold War. Delusions and hallucination, like ideas of reference, put the self at the center of the world. This is perhaps the greatest mischief in Akiva Goldsman's fictionalization. He has eliminated the driven egocentricity—the drama of the self; Crowe's fictional paranoia is an altruism gone berserk.

At this point, a psychiatrist or a Russian agent (we are still unsure which), turns up (played by Christopher Plummer), who not only locks Nash away, but forces insulin coma therapy on him to the point of what looks like prolonged grand mal convulsions—a Ron Howard exaggeration. Somewhere in this process we finally discover, along with his wife, that Nash is psychotic and that much of what we took for real was madness.

The real Nash, like other celebrities, was a patient at McLean Hospital and confined to Bowditch, the ward made famous by the poet Robert Lowell, whom Nash encountered there. Sadly, there would be many subsequent hospitalizations that the film omits, and Nash would eventually be involuntarily hospitalized in a New Jersey State Hospital where he did receive insulin coma therapy. The film understandably compresses his many dreadful episodes of hospitalization into one stay at a pseudonymous hospital called MacArthur. Most certainly, John Nash did not receive the treatment presented in this movie at McLean Hospital. Insulin coma therapy reduces the level of blood sugar that the brain constantly requires. It is a dubious treatment that risks adding brain damage to mental illness. Watching it being done to a genius is horrifying.

Even with modern efficacious treatments for schizophrenia, we face troubling questions about how much they befog the mind and how much they harm the brain. Nash, as shown in the film, concluded that the dosage of thorazine (the standard treatment at the time) prescribed for him at McLean prevented him from thinking mathematically and from functioning sexually. I have no doubt he was correct; antipsychotics control hallucinations but they also can limit serious concentration and have more negative sexual side effects than pharmaceutical houses like to acknowledge. The film, to its credit, also shows that when Nash stops taking this medication he again becomes acutely psychotic.

His wife, played marvelously by Jennifer Connelly, faces the tragic dilemma: will she risk Nash's genius to restore his sanity as the psychiatrist urges her? And the burden on her is heightened when he stops the medication and the hallucinatory CIA agent urges Nash to kill his wife—who stands in the way of decoding work that will save American lives. Heroically, she sends the psychiatrist away (in this film he makes a house call) and tries to connect lovingly with her husband. Placing her hand on his heart and his hand on hers she explains that their touching is real and the heart is the compass of reality. In this melodrama, her love and his reason combine to rescue his sanity.

In real life he was committed to a state hospital; she divorced him and came close to marrying one of his colleagues. Nash would subsequently spend years in Roanoke, living with his mother who was suffering from alcoholism. He would eventually return to Princeton where his former wife put him up and he became the resident madman of the campus, spending much of his time in the library. Unkempt, unshaven, and now chronically insane, he was only one step up from being one of the homeless mentally ill. The tolerance of the math department at Princeton, the concern of his colleagues, and his ex-wife kept Nash from taking that last step down. He had refused all anti-psychotic medication since 1970 and had been delusional for more than a decade. Psychiatrists would have said he was hopeless, but in 1990 a turning point came: Nash began to talk with a mathematician who was working on a problem that had always interested him. Instead of obsessing about messages from aliens he once again turned his mind to mathematics. Slowly, he recovered—or, stated more cautiously—went into remission. Other mathematicians began to realize that he had regained his sanity and over time he reentered the academic world. Although the biography suggests he did this entirely without medication, in the film he acknowledges accepting a little of the newer medications. I have no idea which story is true, but surely a great deal hangs on that truth. Very few people recover the way Nash has (researchers dispute whether it is more or less than one in twelve), and he may have done it without medication. There are already advocates who have long opposed medication making new claims based on the Nash and Helfgott stories.

Life is uglier and more complicated than movies. The screenwriter did find an imaginative way to capture Nash's claim that he cured himself with reason. There is a moment in the movie when Nash suddenly has the insight that his roommate's niece never gets older—a logical proof that allows him to recognize that his mind has been playing tricks on him. He is a problem-solver and so he solves this problem slowly—to use his analogy—like an overweight person who sticks to a diet. The other half of his cure—the movie myth that his wife's love rescued him—is also fiction and the emotional high point of the movie. In an imagined Nobel speech, he is shown speaking to dignitaries gathered from around the world. He explains that he has explored the physical and the metaphysical, logic and reason, but what is real is love, and he learned that from his wife. This Hollywood redemption speech puts the face of humility on Nash's unyielding egocentricity and arrogance. It brings tears to ones eyes, even when one knows better.