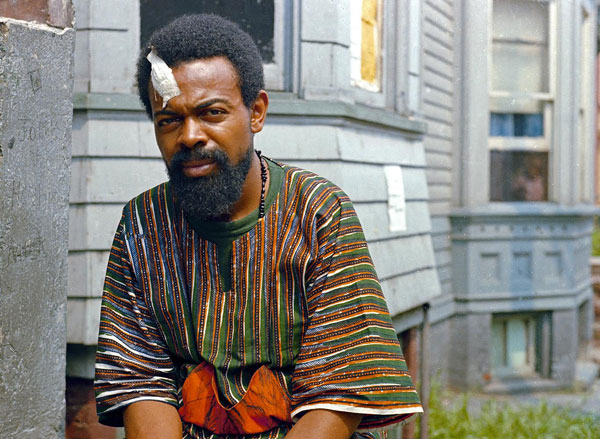

Amiri Baraka in July 1967, shortly after he was injured in the Newark riots. Photograph: AP Photo.

Amiri Baraka in July 1967, shortly after he was injured in the Newark riots. Photograph: AP Photo.

Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn: The Collected Letters

Edited by Claudia Moreno Pisano

University of New Mexico Press, $59.95 (cloth)

The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley

Edited by Rod Smith, Peter Baker,

and Kaplan Harris

University of California Press, $65.00 (cloth)

Disentangling a writer’s life from its surrounding history is a nearly impossible task, partly because history takes many forms. Samuel Pepys had the 1666 Great Fire of London to record in his diary; in a 1963 letter to the poet Edward Dorn, Amiri Baraka describes getting beaten up by the cops.

One value of a writer’s correspondence is the glimpse it offers of the private life behind the public one, although often the two become synonymous as the writer becomes more famous. And while letters might reveal a writer’s sense of current events, these are frequently secondary to literary or intimate concerns, even among the politically committed. Thus Claudia Moreno Pisano’s approach in editing Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn: The Collected Letters is to scatter pieces of historical and political context around the personally revealing materials she has studiously compiled. For the more massive Selected Letters of Robert Creeley, edited by Rod Smith, Peter Baker, and Kaplan Harris, the task is to annotate a vast range of biographical and literary references, but only after sifting through 10,000-plus letters and—according to the Stanford University libraries, where Creeley’s archives are housed—almost 15,000 emails.

“Artists are the antennae of the race,” Ezra Pound once wrote, by which he meant they are historically attuned. Allen Ginsberg’s reading of “Howl” at San Francisco’s Six Gallery in the fall of 1955 may have helped kick-start the postwar counterculture, but that gesture is inseparable from Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus less than two months later. This fundamental conjunction of alternative cultures and social movements is at the heart of the Baraka-Dorn correspondence, even if the two writers weren’t entirely conscious of it at the time. It makes sense that Baraka and Dorn began writing to each other the year before Baraka’s politically formative 1960 trip to Cuba.

Baraka initially wrote Dorn out of the blue and encouraged him to send something for the magazine Yugen, which he was editing with his then-wife Hettie Jones. One of the most remarkable aspects of the correspondence is how consistently and energetically Baraka supported Dorn’s work, even as his own literary reputation grew. Where he once helped place Dorn’s poems in mimeographed magazines and published his first two books with his own Totem Press, he was soon showing Dorn’s manuscripts to agents and mainstream publishing houses. Baraka’s championing continued until the end of this phase of their correspondence when, in a final letter, he asked Dorn if he’d like to take Baraka’s place at what became the landmark Berkeley poetry conference during the summer of 1965, a gesture that testifies to the strength of their connection, the affection between their families, and the shared progressive politics Baraka knew Dorn would take with him.

Dorn offered loyal friendship and openness to Baraka's chronically agitated state.

Dorn reciprocated Baraka’s half decade of generosity as best he could, but during much of this time he was living in poverty with a wife and three children in isolated Pocatello, Idaho, and working as an entry-level college instructor. A student of Charles Olson’s at Black Mountain College in the early 1950s, Dorn grew up in Depression-era rural Illinois. He wandered the American West throughout the ’50s, before securing his first teaching job at Idaho State University. When Dorn started a magazine of his own, Wild Dog, in 1963, he solicited poems from Baraka and asked him to write a column. But what Dorn really seemed to offer was loyal friendship and openness to Baraka’s chronically agitated state. According to Jones, as quoted in Pisano’s editorial notes, “Roi was to tell me, soon, that Ed Dorn was the only white man who understood him.” This was in 1964, not long before Baraka concluded, for the time being, his transactions with the white world.

The decade branded “the sixties” is considered by various historians of the period to have lasted from circa 1965 to 1975 (the first time I heard this proposed, in fact, was in an undergraduate class I took with Dorn), and it is not a coincidence that Baraka left his family and white friends to move from the East Village to Harlem in 1965. If anything, Baraka was sick of the personal—both his own and downtown bohemia’s narcissism—and was looking to subsume it within the socio-political, which he did increasingly into the ’70s, as he moved through his black nationalist and Marxist stages. Dorn would make his own break later that same year, moving to England for a better teaching position. Relocation provided him the slightly distanced perspective that would help shift his poetry from an intimate lyricism to the more clinical forms of political commentary that laced his work in the decades to follow. It would also give him just the right degree of removal from the American West to re-imagine it in his epic poem Gunslinger (1968–75).

This restlessness reconnected Baraka and Dorn in the 1980s and especially the ’90s, as Baraka saw that Dorn still refused to settle down—or, to use a phrase that has been rendered mostly obsolete these days, “sell out.” Baraka seems always to have been deeply restless; so, too, was Dorn in his own geographically and ideologically nomadic way. In The Collected Letters, readers witness Baraka involved with multiple women: in addition to his two children with Hettie Jones, he has one with Diane di Prima, with whom he also edits the poetry journal The Floating Bear. He writes poetry, fiction, nonfiction, plays, reviews; appears on television and at symposia; wrangles with James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, and Andy Warhol; smokes lots of pot (as does Dorn) and does heroin (it makes him sick every time, but he keeps trying). Perhaps most excitedly, the letters show Baraka discovering avant-garde jazz musicians such as Thelonious Monk, Cecil Taylor (who, like Baraka, spent time in Bellevue Hospital with hepatitis after using dirty needles), and Ornette Coleman—listening to them play, hanging out with them, collaborating. Baraka’s unadulterated enthusiasm for this scene is palpable beside the general crankiness that he and Dorn, like so many younger poets, exhibit about poetry and fellow writers. This excitement is two-pronged, indicating his growing disillusionment with the predominantly white avant-garde poetry community, and his desire to participate more fully in an alternative culture where marginality was less a choice than a political condition to engage.

Throughout it all, Dorn does his best to keep up, reporting on poets he sporadically sees, such as Creeley and Olson, with whom he is corresponding. He buys jazz records to supplement the ones Baraka sends him. It doesn’t help that much of Dorn’s side of the correspondence is missing from 1963 on; in her editorial notes, Pisano attempts to reconstruct some of this unavailable content.

Dorn’s battle is with small-town conservatism and provincialism; Baraka’s—in more conventional avant-garde style—is with the bourgeoisie, whether his own parents, black intellectuals, or the cultural landscape at large. Baraka seeks an active confrontation with power structures, Dorn less so, although early in the correspondence he tells Baraka that he envies his “social radicalism.” At one point, Baraka describes an essay he is planning to write: “It will probably be a long piece, full of all the bullshit and non-specific invective I’m always capable of, but also, I’d hope, crammed full of some kind of new politics.” The best of this sentiment—the self-awareness, the humor and play, the sense of outrage, the oppositional politics—would continue to unite their work until their respective deaths: Dorn’s in 1999; Baraka’s, earlier this year.

• • •

In one of the handful of explicitly political moments the editors have chosen to include in The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley, Creeley writes the State Department to decline their sponsorship of a trip to Pakistan due to the “growing dilemma” in Vietnam. This is the spring of 1966, somewhat early in the anti-war movement, partially confirming Pound’s dictum. Creeley goes on to say: “I am very blessed to share a community with other men in the act of writing, and it is their respect and belief that I am also much aware of.”

In the 1950s and into the ’60s, Baraka, Dorn, and Creeley each endeavored to get their writing into the world, supporting each other and seeking affirmation. Writing to Olson in 1959 from even-more-isolated-than-Pocatello Guatemala, where he was teaching, Creeley compares literary correspondence to a “goddamn delicatessen”: “So if I don’t make the menu, I don’t make the scene.” But eventually Creeley “made it,” as did Baraka. Dorn’s reputation has remained a bit more willfully underground, although the past decade has seen increased public exposure, culminating in 2012’s Collected Poems. After Dorn’s death, Baraka remained an important figure in helping to promote the work.

Because the selected Creeley letters span an entire life, they are less relentlessly personal than the ones Baraka and Dorn exchanged as young poets. Once Creeley—his fame growing—secures a stable teaching job at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1967, there is more business to conduct, and his letters lose some of the agonizing they shared with the Baraka-Dorn correspondence, except for touching ones he sends to Bobbie Louise Hawkins in the early to mid-1970s while they are in the process of separating. Creeley is much better at providing feedback on his correspondents’ work than either Baraka or Dorn is with each other, and while it would be difficult to extract a poetics from the Baraka-Dorn correspondence, Creeley can be astute at describing his and others’ writing: in a letter to William Carlos Williams from January 1960, Creeley casts his own poems “in the term of the building, not in the ‘what’.” Also of note is the email Creeley sends to Smith in 2003 advising him on how to organize these letters, suggesting the editors fashion a map as well as tell a story. The fullness of either of these remains up for debate because, despite being packed with all kinds of fascinating details, the volume’s almost exclusive focus on Creeley’s letters to his family and to other noted poets yields a tale not much different—and if anything a bit more circumscribed—than the one that is already known.

When I was a graduate student of Creeley’s at Buffalo in the mid-nineties, there was a technology services room in the bowels of one of the architecturally severe buildings, built as part of a riot-proof campus in the wake of ’60s student activism. Email had just arrived on the scene, and you went to the room to get printouts of your messages. Creeley picked up stacks of his email correspondence there before the service was discontinued. It is possible that one of those early printouts made it into this selected letters, which concludes with a series of short emails—ironically, the very technology that may render books such as these extinct.