It takes one fool to drop a brick down a well, but more than ten wise men and women to extricate it. Eight years of the Bush-Cheney policy on Iran provide compelling support for this ancient Persian wisdom. What can we do to extract the brick from the well? What policies should the United States adopt toward Tehran?

Two answers dominate current discussion. The first advocates a grand bargain with the Iranian regime: we provide security guarantees and convince them that “regime change” is no longer part of U.S. policy; in return, the regime abandons its nuclear ambitions. The second proposes to continue the Bush policy: the Islamic Republic gives up its enrichment activities; we respond by opening discussions. The first strategy offers what the regime most covets before starting to talk; the second insists that the regime surrender its most important bargaining chip before negotiations begin.

Neither approach is very promising. Moreover, they share a common weakness. Both concentrate on Iran’s nuclear program and forgo any concern for the fate of human rights and democracy there. That is why many Iranian democrats fear a Libyan scenario, whereby an oppressive regime promises to dismantle its nuclear program in exchange for American and European good will. As a practical matter, “good will” means little more than a disregard for human rights violations in the country graced by it.

To find an alternative strategy, we need to step back from the current impasse and consider a deeper point of convergence between the United States and Iran.

For the United States, the big “Iran problem” is the country’s nuclear program and the regime’s support for such groups as Hezbollah and Hamas. For the Iranian people, the Iran problem lies primarily in the despotic, incompetent, and corrupt nature of the current regime. The solution to both Iran problems is an Iranian democracy, made by the Iranian people, for the Iranian people.

• • •

Despite its unsavory government—the most glaring despotism in the Muslim Middle East—Iran has a history and social structure well-suited to democratic renewal. Powerful movements for democracy have been at work in Iran for more than a century. Indeed, many of the problems now plaguing the Iraqi constitution—such as reconciling secular democrats’ demands that all citizens be considered equal and the Islamic Sharia mandate that women and people of other faiths be afforded unequal status—were addressed by Iranian democrats between 1905 and 1907. Moreover, Iran now has an ascendant middle class and growing technocratic class, economically enfranchised women, urbanism, a strong civil society, and widespread democratic discourse. It thus meets every sociometric prerequisite for democracy more completely than any other Muslim nation in the region.

If creating democracy in Iran must be the work of the Iranian people, why even talk about an American role? Those who are rightfully wary of U.S. interventionism, or simply distrust the U.S. government’s intentions, suggest that the project of building democracies in Iran and elsewhere is not America’s business. Furthermore, some believe that U.S. culpability in the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Mohammad Mossadeq in 1953 not only disqualifies the United States from credibly taking part in discussions of Iranian democracy today, but also has created in Iran a permanent state of distrust toward America.

The truth about Iranian attitudes is more complicated. From 1941, the beginning of serious U.S. involvement in Iran, until 1953 and the fall of Mossadeq, the United States was considered by many Iranian nationalists and democrats—including Mossadeq himself—an ally in their fight against British and Soviet colonial influence.

From the overthrow of Mossadeq until 1988, Iranian views were generally far less favorable, in part because of the perceived American role in the 1953 coup, in part because of U.S. support for the Shah. Then, the United States sided with Saddam Hussein during Iran’s eight-year war with Iraq (1980-88). And throughout the Cold War, the Soviet Union endlessly reaffirmed the vision of the United States as hegemonic imperialist force.

The advent of the Obama administration may herald a new beginning in relations between the two countries. But the possibilities of renewal could easily be squandered.

But with the end of the Iraq War and collapse of the Soviet Union, perceptions again shifted. European countries, as well as Russia and China, studiously overlooked Iranian human rights violations, and continued to expand their trade with the regime, whose oppressive and adventurous policies isolated the nation and tarnished its global image. The United States was the only major power willing to stand up to the ruling clerics. And because the enemy of an enemy is a friend, America reemerged as a potential ally in the minds of many Iranians..

Against this background, the Bush foreign policy created a double bind for Iranians. On the one hand, the Bush administration’s tough talk against the clerical regime has had an enthusiastic audience among some in Iran. On the other hand, Iranians realized that American policy in the Middle East, particularly in Iraq and Afghanistan, strengthened the worst elements in the Islamic regime. These foreign policy mistakes also helped drive up oil prices, which allowed the Iranian regime to further consolidate its power. All of this was made worse by the inexplicable policy of grouping Iran with an “axis of evil,” just as Mohammad Khatami’s reformist government was preparing the ground for a rapprochement with America.

After years of erratic American policy and mutual distrust, the advent of the Obama administration may herald a new beginning in relations between the two countries. President Ahmadinejad’s (albeit-sermon-like) note of congratulation to Obama on his victory is a promising sign. Yet, during that same week, top clerics of the regime, including Ayatollah Khamenei, reverted to some familiar rants against the United States, underscoring the difficulties of the path forward. Between the arrogance of power—American or Iranian—and the political paralysis that inevitably results from a culture of victimhood, the possibilities of renewal could easily be squandered.

• • •

In view of these dangers, it is fortuitous that democracy-promotion in Iran may now fit with the long-term strategic interests of the United States. The post-war policy of supporting corrupt, tyrannical regimes in the Middle East so long as they sided with the West (in particular the United States) has turned out to be a losing proposition for both the United States and the region. In the Muslim Middle East today, rulers have used this support to follow a scorched-earth policy, eliminating all viable democratic alternatives and leaving a lone unhappy choice between an entrenched regime and Islamic radicals. In Iran, however, three decades of power have deprived these radicals of much of their appeal and legitimacy. The viable alternative to the status quo is democracy, and the United States can play a constructive role in making this transition possible. But American success will depend on the acceptance of a few new cognitive and practical axioms.

Conventional discussions about U.S. policy and democracy in Iran focus on the role the U.S. government can or should play in the process. But in a democracy, citizens can and sometimes do influence foreign policy. Their vigilance and care in protecting democracy at home can promote democracy elsewhere. For example, popular international solidarity with the black majority’s fight against the apartheid regime in South Africa was a key element in its demise. Citizens themselves, not the often-clumsy, over-reaching state, can be the best ambassadors of democracy. Concerned Americans can help the democratic process in Iran by pressuring the U.S. government to avoid unwise policies. The worst policy would be an attack on Iran. The National Academy of Sciences and the Committee of Concerned Scientists, which warn that using nuclear-tipped bunker-busting bombs to destroy fortified underground Iranian nuclear sites will kill hundreds of thousands of Iranian civilians, offer models of reasoned public argument. Voters, activists, and civic organizations should rank opposition to a military option in Iran high on their agendas.

Iranian democratic advocates deserve and require progressive backing.

There are other ways Americans can show solidarity with the Iranian democratic movement. The anti-imperialist left must fight a tendency, among some representatives, to spare the mullahs harsh criticism because they “stand up” to American hegemony. An unfortunate romance developed between some Western intellectuals and the clerical regime that came to power after the 1979 Islamic revolution. Michel Foucault’s brief infatuation with Ayatollah Khomeini and the Ayatollah’s “critique of modernity” reminds us of such follies. In Afghanistan the Taliban were unbendingly anti-imperialist. Yet they were arguably more destructive than any imperial domination. The Iranian regime is similarly anti-imperialist, but it does not merit the support of progressive forces in the West.

Rather, Iranian democratic advocates deserve and require progressive backing. Among these advocates, none are more deserving than the Iranian women in the movement. In the last few months, they have focused their energy and formidable organizational skills in collecting one million signatures in defense of constitutional equality for women. They have forced the regime to retract some of its more egregious misogynistic laws, for example, a proposed law that would have allowed men to take additional wives without the consent, as existing law provides, of the first wife.

The regime’s retreat on this specific law, however, was tactical. Before long, the clerics introduced a new law that bans young women from traveling outside their cities of birth to attend university. The law is a de facto negative quota against women, who are becoming a larger and larger majority in the country’s highly competitive university system. It also further limits their movement around the country. American feminists can oppose these efforts by helping raise awareness of the struggle of Iranian women and the regime’s misogynistic laws and practices. Moreover, by extending privately funded scholarships, internships, and research grants to Iranian women, they can enrich the feminist movement in Iran and help educate the West about the rich diversity of thought and practice among Iranian women today.

The Iranian democratic movement also needs support in its struggle for religious freedom and equality. Iran’s shrunken Jewish population—down to 25,000 from a one-time high of 150,000—lives under constant accusations of Zionism. Yet, while the media has focused on President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Holocaust denials and comments about the state of Israel, sectarian persecution in Iran is not limited to Jews or even non-Muslims.

Shiism is the state religion in Iran, and every religious minority struggles for the right to worship in private. The Bahá’í of Iran are arguably the most persecuted religious minority in the country. Their youth are barred from public universities if, on their application forms, they indicate their faith. Sunni Muslims (10 percent of the population) have suffered recent attacks on their places of worship by Shia vigilantes. Even Shias whose practice differs from official dogma find themselves under pressure. Reformist thinkers like Yousefi Eshkevari, Abdulkarim Soroush, and Abdullah Nouri face constant attacks and threats, and debate even among traditional ayatollahs is silenced.

Civil and political rights, too, are a priority for many Iranian groups. Ethnic minorities fight for the right to speak their own languages and have a more active role in managing their own affairs. Iranian workers try to establish independent labor unions. Iranian students, writers, poets, musicians, painters, and filmmakers agitate for basic democratic freedoms and against the regime’s increasingly draconian censorship. Recently, even merchants of the bazaar—for a century the most reliable source of support for the clergy—successfully organized a strike to fight a proposed tax.

There are also millions of Iranians who are addicted to drugs, particularly heroin, and thousands suffering from AIDS. Their plight has remained largely hidden from the Iranian public and the rest of the world. Concerned citizens in the West can help give voice to those abandoned by the regime.

The Islamic regime has not only resisted attempts by the American government to advance democratic movements and causes within Iran; it has also used the Bush administration’s clumsy gestures of support to label all Iranian democrats agents of American colonialism. Support from American citizens would be more difficult to resist or dismiss. For example, the official travel bans against members of the regime that the United States and United Nations have considered will likely have little impact on the regime’s ability to maintain its power. Yet if a leader of the regime meets massive demonstrations—demanding equality for women, religious tolerance, and an end to despotism—every time he travels, the Iranian democratic movement will be heartened at the expense of an embarrassed regime in Tehran.

One might argue that the Iranian regime’s apparent indifference to, even disdain for, global public opinion would nullify any effect foreign protests could have. But this stance is a bluff. The regime is highly sensitive to its image in the West. American progressives, like their peers in other democracies, can become a force for democracy by exposing the Iranian regime and holding it responsible for every breach of human rights in the country. Through increased contacts and solidarity with their Iranian counterparts, organizations from labor unions and religious groups to professional and trade associations can help the nascent Iranian civil society survive the regime’s continued onslaught.

• • •

Citizen diplomacy and solidarity must become a pillar of a new American policy in Iran. But the new U.S. administration can also play a constructive role in promoting Iranian democracy. It should first abandon unilateralism. Instead of acting as masters of the political universe, forcing “Western” democracy on recalcitrant “natives,” the new administration can start by accepting the common-sense truth that democracy cannot be exported, certainly not at the point of a gun or a guided missile. Democracy is not a Western gift, but rather part of our common human heritage.

A new American president whose first name, “Barack,” is Arabic for “blessed” or “God’s beneficence,” and whose middle name, “Hussein,” is the name of Shiism’s quintessential martyr and third Imam, offers a greater challenge to the clerical regime than a Bush administration that talked of “crusade” and received support from people who sometimes dismissed Islam as nothing short of a heresy.

The two countries should negotiate directly and unconditionally. This abstention from conditions must be mutual. Neither the United States nor the clerics in Iran can declare an issue off the agenda. For the United States, the key to the success of such negotiations is to strike a fine balance: to reassure the clerical regime that the United States is no longer planning for regime change while making clear to Iranian democrats that concern for human rights in Iran will not be bargained away for any concession by the regime.

The Bush administration’s offer of more than $70 million for those aspiring to topple the clerical regime was exactly the wrong idea. It found no takers among Iranian democrats, but it did lead to the emergence of dozens of newly minted “Iranian democratic groups,” each vying for a piece of this largess. The fund thus played into the hands of the regime, allowing it to attack all activists as agents of the American project. No less damaging to the democratic cause in Iran would be an American policy that shows no concern for Iranian democratic aspirations.

Dehumanization of Iranians has reached harrowing new heights in the United States. Prominent Americans have invited the United States to “obliterate” it.

Finding that optimal point—showing concern for Iranian democracy but resisting the temptation to dictate—will be challenging, though not impossible. But why would the Iranian regime agree to this kind of relationship? After all, the clerics understand that normal relations with America threaten its power. Yet they also know that the oil bonanza is ending and that economic disaster may follow. While détente with the United States may be dangerous, it may also provide the only antidote to the still graver danger of an economic crisis that deprives the regime of all legitimacy and power.

Along with civic solidarity and renewed negotiations—indeed, a prerequisite to their success—is an end to the demonizing of Iranians that has resulted from efforts to isolate the regime.

The Islamic regime in Iran has tried its own hand at demonizing by reducing the complexity of American society to Abu Ghraib and renditions. But dehumanization of Iranians has reached harrowing new heights in the United States. Prominent Americans have invited the United States to bomb Iran—“obliterate” it, to use Hillary Clinton’s words. Bill O’Reilly suggested blowing it “off the face of the earth.” These genocidal threats produced little public outrage in the United States. The road to democratic contact cannot be paved with intimidation and insult.

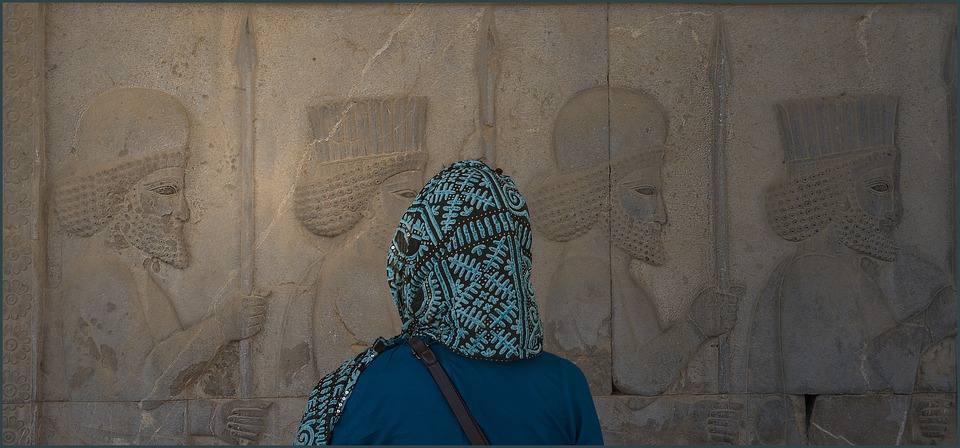

Greater access to the rich human diversity of contemporary Iranian society, a diversity and democratic disposition that resists the regime’s efforts at control, might foster a shift in American attitudes. The Iranian regime tries to present to the world an image of Iranian people as docile, pious, even xenophobic. Iranian democrats, on the other hand, have been trying—through film, music, painting, poetry, and fiction—to convey a very different picture.

Regular civic contacts—inviting Iranian artists, musicians, filmmakers, scholars, and human rights activists to the United States—would be the natural first step. Sports exchanges, for which there are some precedents, and visits by tourists and business groups to Iran and the United States, can help create an atmosphere of mutual trust, a necessary prelude to the success of both citizen and state support for democracy in Iran.

Restoring decent relations between the United States and Iran will require a deliberate, prolonged process. We can count on malign efforts on both sides to undermine any serious process of normalization, or deprive it of democratic substance. Only the wisdom and humanity of concerned and informed citizens, combined with a new prudence in American policy, can navigate the treacherous waters ahead. And the only acceptable end to this terrible journey is democracy in Iran, security in the Persian Gulf, and new, mutually beneficial relations between Iran and America.