As many Americans anticipate the likely nomination by a major party of a woman for president—the New Republic cover of July 14 calls Hillary Clinton “Inevitable”—it is worth pausing to reflect on how women’s participation in politics has changed over the course of American history. In eras before Clinton, Sarah Palin, and Nancy Pelosi, participating in politics was not only nearly impossible for women but was also considered a violation of what it meant to be a woman.

A just-published article in the Journal of the Early Republic by Emily J. Arendt illustrates the stark contrast between then and now. Arendt tells the story of the Ladies Association of Philadelphia, “the first female voluntary association in the United States,” formed in 1780 to assist Continental soldiers. The domestic nature of its work and awestruck reaction observers had to activist women underlines the era’s low expectations for women’s participation in civic life. Those low expectations lasted—despite the notoriety of early feminists—well into the twentieth century, making the last half-century a sharp historical departure for women in politics.

Shirts

As Arendt tells the story of the Ladies Association, things were bleak in 1780 for the rebel cause. Commanding General Washington faced mutinies by underpaid, underfed, and underclothed soldiers and kept calling for more support from the Continental Congress. Little was forthcoming. Using a model that only men had employed before—creating voluntary associations to establish schools, libraries, fire-fighting, and the like—about three dozen wives of wealthy men joined together in a formal association to collect funds for the army. In a dramatic departure from propriety, they stepped out of their homes to solicit funds door-to-door throughout Greater Philadelphia. Elite women such as these were typically sheltered from public life. Knocking on the doors of lower-status people reversed the typical pattern of formally “receiving” lesser folk in their own homes, if receiving them at all. The Ladies Association ended up collecting 300,000 Continental dollars from 1,400 residents. Upon Washington’s suggestion, the Association used the funds to buy linen which volunteers then sewed into badly-needed shirts for the infantrymen. Women in a few other states imitated the Philadelphia ladies.

Observers, including European writers, found this ladies’ campaign, which would seem almost mundane today, remarkable. Working-class women had been political if what we mean by “political” includes street action like food riots. But for “respectable” upper-class women to be so active, in an association, and to be so public was noteworthy for its time. “They took up a civic activity previously defined within the realm of ‘masculine public virtue.’ The ladies who went door to door collecting funds appropriated this conventionally masculine form of community building and carved out a space for the display of feminine public virtue.”

Tippecanoe’s Ladies

A 1995 paper in the Journal of American History by Elizabeth Varon provides a story set two generations later in 1840s Virginia. The Whig party was the first to explicitly mobilize women in presidential campaigns, in this instance to support William Henry “Tippecanoe” Harrison (and Tyler, too). Party leaders urged women to attend rallies, give speeches, write pamphlets, display campaign paraphernalia, and to pressure their menfolk. Whig statesman Daniel Webster gave a speech in which he articulated a new view of women’s role. Electoral campaigns had been seen as part of a dirty public world fit only for men, women being naturally assigned to nurture peace and harmony in the home. “What was new about Whig womanhood was its equation of female patriotism with partisanship and its assumption that women had the duty to bring their moral beneficence into the public sphere. Whig rhetoric held that women were partisans, who shared with men an intense interest and stake in electoral contests.” Middle- and upper-class women who were active in moral uplift movements like missionary societies and temperance movements should bring those sensibilities to partisan politics as well, argued the Whigs. “Partisanship,” writes Varon, “was indeed a consuming passion and pastime for antebellum Americans,” so much so that some of the rhetoric suggested that marriage across party lines was frowned upon (a view that seems to have been resurrected recently; see here).

At first, the Democrats scoffed and ridiculed the Whigs’ mobilization of women, insisting on the notion of politics as a manly struggle, but within a few political cycles, they, too, were contesting the women’s indirect “vote.”

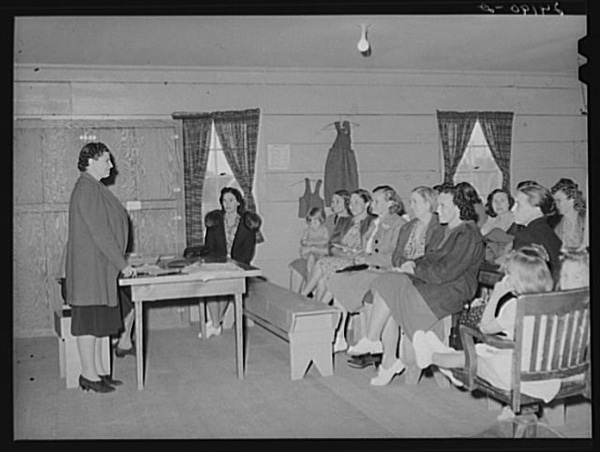

More Motherhood Politics

A century later, women were able to vote and a few held office—a radical change. But there was still a special tone to women in politics, a domestic tone. In a 2004 paper in the Journal of Social History, Robin Muncy describes the politics of postwar suburbia during the couple of decades leading into the 1960s. In a case study of Montgomery County, Maryland, Muncy shows how many women moved, perhaps even drifted, into local politics through their involvement in the cooperative nursery school movement. This sort of voluntary association, descendant of the Philadelphia Ladies Association, emphasized the role of women as caretakers and as activists within the “women’s sphere.” But issues arose that needed broader activity, some of the mothers developed organizational skills, and a few moved into wider arena of town and county politics.

Just Politics

The ‘60s do seem here, as in other respects, a watershed, when women became directly active in electoral politics the ways men did, no longer just as representatives of the domestic sphere.

The point was perhaps most starkly made by Hillary Clinton herself—a 1969 college graduate—when, during the 1992 presidential campaign of Bill Clinton, she firmly told a reporter, “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was to fulfill my profession which I entered before my husband was in public life.” The profession she literally refers to here is the law; the real profession, everyone understood then and understands now, is politics.