Headlines in America’s newspaper of record imply that if you’re not feeling lonely, you may be the lonely exception: “Sad, Lonely World Discovered in Cyberspace”; “Alone in the Vast Wasteland”; and “The Lonely American Just Got a Bit Lonelier.” Add books such as Bowling Alone, The Lonely American, and Alone Together, and you might think that there is an epidemic of loneliness.

An endemic epidemic, perhaps, because we have received such diagnoses for generations. The 1950s—the era of large families, crowded churches, and schmoozing suburbanites—brought us hand-wringing books such as Man Alone: Alienation in Modern Society and the best-selling The Lonely Crowd, which landed author David Reisman on the cover of Time magazine. About a half-century before that, policymakers were worrying about the loneliness of America’s farmers, and observers were attributing a rising suicide rate to the loneliness of immigrants or to modernity in general. And so on, ever back in time. Noted historian Page Smith described colonial Americans’ “cosmic loneliness” and the upset stomachs and alcoholism that resulted. Americans have either been getting lonelier since time immemorial or worrying about it since then.

The latter is more likely. Social scientists have more precisely tracked Americans’ isolation and reports of loneliness over the last several decades. The real news, they have discovered, is that there is no such epidemic; there isn’t even a meaningful trend.

If we turned to historians to measure Americans’ degree of isolation over the centuries, they would probably find periods of growing and lessening social connection. The rough evidence indicates a general decline in isolation. When you think back to, say, a century ago, don’t call up some nostalgic Our Town image (although alienation is a theme in that play). Picture more accurately the millions of immigrants and jobless, farm-less Americans trekking from one part of the country to another, out of touch with family and likely to be trekking again the next year.

Skeptical readers may vaguely recall an oft-repeated “factoid” that Americans have fewer close friends than ever. In 2006 sociologists at Duke reported, based on comparing two General Social Surveys, that the percentage of Americans who had no one to confide in tripled between 1985 and 2004, from about 8 to about 25 percent. Headlines ensued: “Social Isolation: Americans Have Fewer Close Confidantes” (NPR), “Social Isolation Growing in the U.S.” (Washington Post). In 2009 the report’s authors conceded, under pressure from a critic, that the valid estimate for 2004 isolation could be as low as 10 percent. (Disclosure: I was the critic.) Even that figure is likely to have been a technical error and is certainly an anomaly. One coauthor recently admitted that the finding was unreliable.

Several surveys conducted from 1970 through 2010 have asked Americans the same questions about their social bonds. The results, which I compiled in Still Connected (2011), show that some aspects of social involvement have changed since the 1970s. In particular, Americans these days sit down to fewer family dinners and host guests in their homes less often; eating and sociability continues, but outside the home. Americans communicate more frequently with their relatives and friends. Critically Americans are not discernibly more isolated—few were isolated at any point in those decades—and Americans remain just as confident of the support family and friends provide.

Many commentators are sure that new technologies have made us lonelier, but people use new media to enhance their existing relationships.

Loneliness is different from isolation. People who report that they are lonely are not much likelier to be socially isolated than people who do not. Notably, the lonely are likely to lack one specific tie, to a spouse or partner. Roy Orbison knew that: “Only the lonely / Know the heartaches I’ve been through / Only the lonely / Know I cry and cry for you.” Overall, Americans reported no more loneliness in the 2000s than they did in the 1970s. (In one series of polls, Americans reported the most loneliness right after the JFK assassination and again right after 9/11. It may be another way to report depression.)

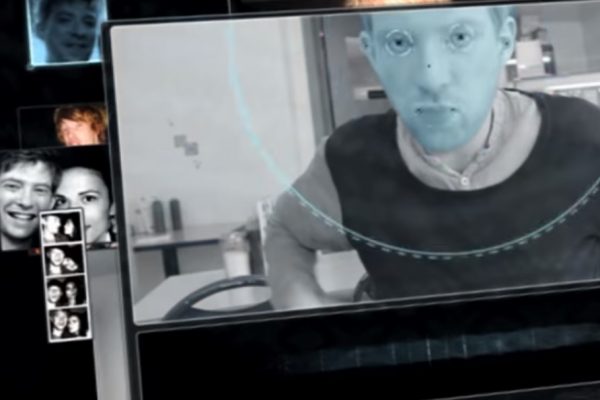

Many commentators are sure that new technologies have made us lonelier. Literary critic William Deresiewicz wrote in 2009 about “the loneliness of our electronic caves . . . . The more people we know, the lonelier we get. . . . We have given our hearts to machines, and now we are turning into machines.” In The Atlantic, novelist Stephen Marche blames Facebook: “We have never been more detached from one another, or lonelier. . . . We live in an accelerating contradiction: the more connected we become, the lonelier we are.” (Remind me not to “friend” these guys; they sound so sad and overwrought.) MIT’s Sherry Turkle, in Alone Together, reports on the torturous self-doubts that come with online friendship. Can she, her friends, and the young people she interviews really sustain intimate ties through their ubiquitous screens?

The first systematic studies of the Internet’s social side suggested that early adopters were hiding away from people. But as Internet use became widespread, the findings changed. Robert Kraut, a leading researcher who had raised early warnings explicitly recanted; the resulting Times headline was, “Cyberspace Isn’t So Lonely After All.” People using the Internet, most studies show, increase the volume of their meaningful social contacts. E-communications do not generally replace in-person contact. True, serious introverts go online to avoid seeing people, but extroverts go online to see people more often. People use new media largely to enhance their existing relationships—say, by sending pictures to grandma—although a forthcoming study shows that many more Americans are meeting life partners online. Internet dating is especially fruitful for Americans who may face problems finding mates, such as gays and older women. Finally, people tell researchers that electronic media have enriched their personal relationships.

People typically turn new technologies into devices for doing what they have always wanted to do. And people like to stay in touch. A century ago, Americans, especially women, turned two new technologies marketed for other purposes, the telephone and automobile, into “technologies of sociability.” Developers of the Internet meant it to be a tool for the military and for scholars, and only a few imagined it might even serve business. Now users have made the Internet a largely social technology. (Not all new technologies develop this way; books and television are other, asocial stories.)

An intriguing exception to the recent hand wringing is Eric Klinenberg’s new book Going Solo. (Second disclosure: Klinenberg was a student of mine.) A far greater percentage of people now live alone than in the 1950s, and he interviews hundreds of them. However, most of them, Klinenberg stresses, choose to live alone. They’d rather pay more to do so than to live with kin or roommates. Many want a life partner but would rather live alone than with the wrong one. Critically, he, like other researchers, finds that people who live alone lead, on average, as or more active social lives than do those who live with others. Single women, for example, spend more time with friends than married ones do. (In Age of Innocence, Ellen Olenska tells a puzzled visitor that she likes living alone “as long as my friends keep me from feeling lonely.”)

Klinenberg is no Pollyanna. His 2003 bestseller, Heat Wave, revealed how old people living alone in dangerous neighborhoods died at high rates during the Chicago scorcher of 1995. They boarded themselves indoors and no one checked on them. And in Going Solo, Klinenberg also discusses living alone as a sad outcome rather than a happy option. Still, his overall story is that the great increase in living alone has not substantially increased loneliness. One reason, he suggests, is precisely the new communications technologies.

Loneliness is a social problem because lonely people suffer. But it’s not a growing problem. Moreover, the loneliness that should worry us is not generated by a teen’s Facebook humiliation, a globetrotter’s sense of disorientation, or the romantic languor of a novelist. It is, rather, the loneliness of the old man whose wife and best friends have died, the shunned schoolchild, the overburdened single mother, and the immigrant working the night shift to send money home. There’s nothing new or headline-worthy about their loneliness, but it is real and important.