Narendra Modi: The Man, the Times

Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay

Westland Ltd/Tranquebar Press, $49.75 (cloth)

The physician sat in the corner of his office in Ahmedabad, a map of India’s western state of Gujarat on one side, a map of the human nervous system on the other, his hip leaning against the drawer that I spent weeks trying to convince him to open.

After agreeing to a list of conditions—I could not take any photographs, I could not remove anything from his office—he agreed to show me the drawer’s contents. It was a six-inch stack of letters between two longtime pen pals, the physician and a young man named Narendra Modi, the current chief minister of Gujarat and the official candidate from the Bharatiya Janata Party to contest next year’s elections for India’s prime minister. I took out my digital recorder and began reading each letter aloud. A few days before I boarded my return flight to California, the physician called me to his office.

“Zahir bhai,” he said. It was unusual for him to address me this way—he is in his 60s, twice my age, and “bhai” means brother in Hindi and is used most often with someone older.

“Zahir bhai,” he repeated. “I am very sorry. You cannot use my name in your piece.”

I was not surprised; very few in Gujarat are willing to use their real name when asked about Modi. I told him I would be happy to change his name.

“No, you cannot use my name or my letters or my story. I have three children. Modi will ruin their lives if people know my views on him.”

I pleaded with him to reconsider but he would not budge.

“You do not have children. You do not know what it is like to live in Gujarat. You will return to America eventually. Please, you must understand.”

Unfortunately, I do understand. Two years ago, I started conducting research about the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat riots, a wave of communal violence in which over 1,000 were killed, almost all of them Muslim. One person I interviewed, Nadeem Saiyed, was an eyewitness to the Naroda Patiya massacre in which 97 people were killed by a mob of 5,000. When Saiyed and I met, he insisted on checking my passport to verify my name and told me it was a bad idea for him to talk with me about his work in organizing witnesses to testify that Modi’s was complicit in the Gujarat riots.

A few months after we met, Saiyed was fatally stabbed 28 times two blocks away from my apartment in Juhapura, the Muslim ghetto of Ahmedabad where 400,000 live with limited roads, schools, and drainage lines. Since then, when someone tells me they fear repercussions for speaking about Modi, I have learned to pay attention.

I remembered this as I sat across from the physician. I removed my digital recorder and ran my hands through my hair, now considerably more grey than it was two years ago, and pressed the large, red delete button. The physician smiled, put his hand on his heart, and thanked me.

“I will never be able to finish this story on Modi,” I said, unable to make eye contact with him.

“I know,” he said. “This might be Modi’s biggest achievement. No one will talk about him.”

How do you understand a man like Modi who has convinced nearly everyone around him to remain silent about his life? This is the challenge that faced Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, the author of the excellent new biography Narendra Modi.

Mukhopadhyay is a respected senior journalist who has lived in Delhi for the past 34 years. He is an unlikely choice to become a biographer granted access by Modi to interview him. Mukhopadhyay reported on Gujarat during the riots and wrote an article in The Pioneer that compared Modi to Ariel Sharon, then Prime Minister of Israel. Mukhopadhyay said that while Sharon had “the tag of having a ‘blood tainted past’ the Chief Minister (Modi) is in the process of picking up a similar label.”

So why would Modi agree to sit down with a critic like Mukhopadhyay? For Mukhopadhyay, the answer is simple—if Modi wants to become prime minister, he has to find a way to put his past behind him, especially his role in the 2002 Gujarat riots.

But Modi has never been fond of speaking to the press. In 2008, Modi removed his microphone and walked off camera during a nationally televised interview when he was asked about his role in the Gujarat riots. In fact Mukhopadhyay spends the first part of the book quoting journalists who warn him how difficult it is to interview Modi. One journalist tells him, “Modi can get extremely vindictive if you write reports that are critical of him. All lines of information get blocked so the choice is either to stop any critical reporting or just skim the surface making a few discomforting points here and there but never writing anything that does substantial damage.”

Modi may quote Gandhi, but he is popular because he is not afraid of being un-Gandhian.

Modi is afraid for good reason: there are court cases, both within Gujarat and at the national level, about Modi’s role in the 2002 riots and in a series of extrajudicial assassinations that occurred on his watch in his state, and so he is hesitant to reveal anything that may implicate himself. This is the curious course ahead of Modi: in a year’s time he could end up in the prime minister’s office or—and admittedly this is unlikely—in jail.

Gujarat is known, at least outside of India, as the state that produced Mahatma Gandhi, the frail leader who wore a simple, homespun white cloth and preached nonviolent direct action and the importance of people coming together regardless of caste, religion, or political party. But within India, Gujarat has become synonymous with Modi, who has announced himself as a new type of leader: brash, stylish, prone to bragging about his large chest size, and most significantly for the Indian courts and the international community, unrepentant about his state’s role in the loss of Muslim lives. He may quote Gandhi but he is popular, in short, because he is not afraid of being un-Gandhian.

The riots, Mukhopadhyay argues, gave Modi “his distinct identity—a label which he has displayed brazenly ever since.” But Mukhopadhyay reminds us that focusing too much on the riots obscures key details about Modi’s life that offers insights into who Modi is and what kind of prime minister he would make. The challenge Mukhopadhyay sets himself, then, is to figure out whether—and, if so, how much—the prism of the Gujarat riots distorts his subject.

Narendra Damodardas Modi was born on September 17, 1950 in Vadnagar, then a part of the Bombay state that later split into two, Maharashtra and Gujarat. Modi’s father was a tea vendor, his mother a homemaker, and Modi spent much of his childhood working alongside his father. But it was not a happy childhood, he tells Mukhopadhyay: “I had a lot of pain because I grew up in a village where there was no electricity and in my childhood we used to face a lot of hardships because of this.”

Modi showed a fondness for the Hindu right wing group the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) as a child. The RSS was started in 1925 as a Hindu nationalist movement and reached infamy in 1948 when one of its members, Nathuram Godse, assassinated Gandhi. It was declared a terrorist group immediately after by the Indian government and banned for two years. But today it remains as strong—and hardline—as ever.

There are an estimated 40,000 RSS camps, or shakhas, across the country where Hindu men and young boys gather each morning to chant slogans and perform a series of exercises, often using a long stick. In the landmark report on the 2002 Gujarat riots, “We Have No Orders to Save You,” Human Rights Watch said it was the RSS that was responsible for passing out lists of Muslim-owned business and homes to mobs at the start of the violence.

It was at these camps that Modi’s ideas about the world were formed. Modi’s brother, Somabhai, tells Mukhopadhyay that “[Modi] was always greatly impressed by the fact that only one person gave all the orders in the [RSS camp] and everyone followed the command.”

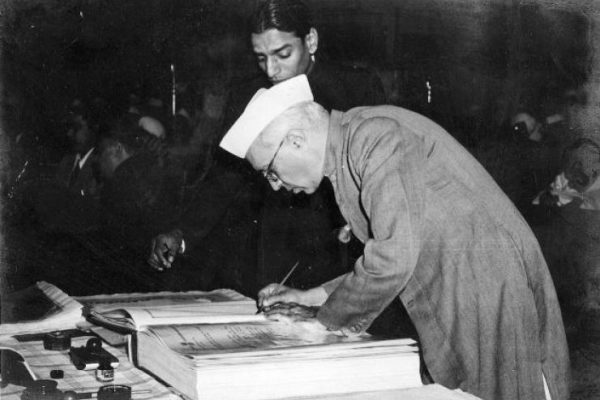

Modi also developed, as Mukhopadhyay writes, “a strong hatred towards the Congress,” the political party that has rule India for most of its post-1947 independence. Modi tells Mukhopadhyay that the anti-Congress sentiment in the mid-1950s was so intense that it “impacted even the mind of the child that I was at the time.” This is the unique thing about Modi—instead of speaking about his poor childhood or his blue collar roots, Modi often talks about his childhood being framed by the trauma of being ruled by the Congress party. For Modi, the problem with the Congress party is not that it is pro-Muslim but that it is not pro-Hindu. Modi has also never forgiven the Congress party for side stepping one of its members, Sardar Patel, a native of Gujarat, in favor of making Jawaharlal Nehru India’s first prime minister. It is partly for this reason that today Modi is erecting statue of Patel in Gujarat that will be taller than the Statue of Liberty. For Mukhopadhyay, it is Modi’s way of announcing a not so subtle message: Gujarat’s proudest son is Sardar Patel, not Gandhi.

But it was more than a contempt for Congress that he displayed at a young age—Modi also showed his trademark unwillingness to be questioned. Mukhopadhyay writes:

This was most evident during my travels through Gujarat. There was one observation routinely made by almost everyone I interviewed while researching for this book—that Modi did not like to listen to any other viewpoints besides his own, that he was authoritarian and did not allow any of his peers to acquire a distinct identity and thereby even remotely pose any threat to him. Most people said that this also reflected a basic insecurity in his personality—a major flaw—and that he was using power to demand—and secure—subservience from those around him. On this matter, most people I interacted with felt that Modi was among the least democratic leaders.

This explains one of the key problems of Mukhopadhyay’s book: we are forced to sift through the limited details of Modi’s life that Modi allows to seep out, which testifies to Modi’s unwillingness to be known. Even though the author was given access to Modi, many subjects were off-limits to Mukhopadhyay, including Modi’s marriage. Modi was betrothed at a young age but abandoned his wife when she was 18 years old claiming that he had never consented to the marriage. Mukhopadhyay says Modi’s marriage is irrelevant, but this is a matter that we, the readers, should be allowed to determine for ourselves. At times reading Mukhopadhyay’s book feels as though Modi is shutting the door on us too.

What Mukhopadhyay does convey is that Modi has always had a passion to be alone. After his marriage dissolved, Modi fled to the Himalayas to become a Sanyasi—a Sanskrit term for a person who abandons worldly possessions and seeks spiritual enlightenment. But Modi returned to Gujarat shortly after to run his family’s tea stall with his two brothers. He became active again in the RSS and earned a reputation for being a skilled organizer. In 1985, Hindu-Muslim violence erupted in Gujarat in response to agitations among Hindus that the Congress party was appeasing Muslims to win votes. Modi saw a chance to mobilize Hindu voters and for the first time, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), often called the political wing of the RSS, came to power in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s most populous city, after the 1986 municipal elections.

If non-Hindus want to live in peace, they should adhere to Hindu traditions.

Modi was given credit as the man who delivered the BJP its first victory in Gujarat, but he also earned a reputation as someone unwilling to take orders from his nominal superiors. Mukhopadhyay says Modi failed to understand that the RSS—not the individual—is the priority in the hierarchy of Hindu nationalist groups. One person who did not share this view of Modi was LK Advani, then the president of the BJP. It was Advani who articulated the ideology of Hindutva, the idea that India is and should always be a nation that places Hindus and Hinduism first. As Mukhopadhyay writes, “The secondary position of Muslims in Gujarat stems from the campaign that there is a need to restore to Hindu past glory that was taken away by Muslim invaders and their supporters.”

In the early 1990s, Advani mounted a chariot and rode across India rallying support to destroy the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, which supporters of the right wing Hindutva movement argued was built over the birthplace of Hindu deity Lord Ram. Advani’s rath yatra, or procession, began in the Gujarat city of Somnath, where a Hindu temple was destroyed by Muslim raiders in the 11th century. Advani selected a then-nationally unknown young man named Narendra Modi to ride next to him, as sort of his Arjun, the person who was disciple to Lord Krishna in the Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita. On December 6, 1992, tens of thousands of Hindu extremists, many from the RSS, razed the mosque—built in the 16th century by Babur, India’s first Mughal emperor—sparking riots across India, including in Gujarat. It was Advani’s and Modi’s way of evening out the balance sheet—of saying, Muslims destroyed our temple, we will destroy theirs.

Achyut Yagnik and Suchitra Sheth, the co-authors of The Shaping of Modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva, and Beyond, write that the 1992 riots across India were a turning point, especially in Gujarat:

More than the numbers, the nature and extent of violence were indicative of the collective degeneracy. In many areas a number of houses belonging to Muslims were torched and scores of people were roasted alive. Even children were not spared. Women were gang raped, many in front of their family members.

One Hindu nationalist in Gujarat told the authors, “Muslims will never dare to raise their heads in Surat now. They will have to learn to live in an inferior position as befits a minority.” This, Mukhopadhyay argues, is how Modi defines the Hindutva ideology that is still the core of his worldview. It is not that non-Hindus cannot and should not live in India. But if non-Hindus want to live in peace, they should adhere to Hindu traditions.

The 1992 riots catapulted the BJP to national power for the first in India’s history. Brown University Professor Ashutosh Varshney, one of the world’s leading experts on Hindu-Muslim violence, wrote in a recent op-ed that, “The Ayodhya movement, led by Advani . . . brought the BJP to India’s centerstage. In 1989, the BJP got 11.5 per cent of the national vote; in 1991, 20.1 per cent; in 1996, 20.3 per cent; and in 1998, garnering 25.6 per cent of the national vote, it nearly equaled the vote share of the Congress party, something entirely inconceivable even in the late 1980s.”

But it was not until the devastating Gujarat earthquake in early 2001 that Modi found his chance to jockey for power. The chief minister, Keshubhai Patel, was slow to respond to the earthquake and many critics, even within Patel’s own BJP, found Patel to be inept and corrupt. What Gujarat needed was someone strong, someone unafraid to hold his fist out. After a resounding BJP defeat in a special election in Gujarat after the 2001 earthquake, the BJP’s national leadership replaced Patel with Modi in October 2001. Suddenly the boy who spent the first two decades of his life pouring tea and swearing allegiance to the RSS was now the leader of one of India’s largest and wealthiest states.

Modi’s life—and the life of thousands of others, including my own—would change on February 27, 2002. I arrived in Ahmedabad, Gujarat on February 15, 2002. My grandparents left Gujarat in the 1920s for Tanzania, where my parents were born and raised. I grew up in California but knew very little about my ancestral home. The India I lived was one that I created, but never experienced. After graduate school at UCLA, I received a fellowship to work with the America India Foundation and I was assigned to work in a Hindu slum area of Ahmedabad and to live with a Hindu host family. But my micro-finance career lasted only two days.

On February 27, 2002, a train carrying Hindu pilgrims was returning from Ayodhya where they were building the Ram temple to be placed over the razed Babri mosque. When the train stopped in the Gujarat town of Godhra, an altercation ensued between several of the Hindu passengers and some of the Muslims working at the train station. The train was set on fire, resulting in the death of 58, including 25 women and 15 children. An inquiry into the train burning, lead by former Supreme Court Justice UC Banerjee, determined that it was burnt by accident. That report was later thrown out by the Gujarat Court on the grounds that it was “illegal.” In 2011, a Special Court in Gujarat indicted 31 Muslims and acquitted 63 other Muslims in an attack that the court described as “pre-planned.”

I was staying in an entirely Hindu only part of Ahmedabad when the train was burned in Godhra on February 27, 2002. On the morning of February 28, 2002, a mob walked on my street and demanded that Muslims come out of their homes. They wore saffron colored scarves and carried three-prong swords called trishuls.

“We will teach Muslims a lesson,” the mob shouted. I stood off to the side, praying the Hindu mob would not see me, the lone Muslim, standing in an all-Hindu crowd.

‘Modi is a stud,’ a young man told me. Several women said they have a crush on him.

Around 150,000 Muslims were displaced in Gujarat. In the Hindu neighborhood of Ahmedabad where I lived, life resumed to normal within days of the Godhra train attack. I even remember taking children from my street to see the latest Star Wars movie, as Muslim homes burned across town. This is my most chilling memory from 2002—the violence was so immense but recognized, still up to now, by so few.

Riots are, however, not new to Gujarat and Modi’s supporters are fond of saying that more riots have occurred under Congress’ rule than the BJP’s. But the 2002 violence, as Human Rights Watch reported, appeared to be pre-planned. Meticulous lists of Muslim business and homes were passed out, dozens of Muslim religious sites were destroyed, and many Muslim women have spoken about being gang raped during the riots.

It was not the failure of the state to intervene that makes Gujarat’s violence so unusual. It was that there is evidence to suggest the Gujarat state government encouraged the violence. As Varshney writes, “Unless later research disconfirms the proposition, the existing press reports give us every reason to conclude that the riots in Gujarat were the first full-blooded pogrom in independent India.”

Sanjiv Bhatt, a Gujarat police officer, filed an affidavit in India’s Supreme Court stating that on the evening of February 27, 2002, Modi summoned his top police officers and told them not to intervene to save the lives of Muslims during the violence. In his affidavit, Bhatt claimed that Modi told them to let “Hindus to vent out their anger against Muslims.”

Modi has, again and again, said that Gujarat needs to “move on.” But this is difficult, Mukhopadhyay writes, because “when one travels beneath the skin of Gujarat, the scars and schisms are still evident.” Mukhopadhyay finds communalism “even within the mainstream media, academic, and other sections of the intelligentsia who interact close with the political class.” Modi will eventually disappear from power but the divide will remain, Mukhopadhyay writes, because communalism “is embedded in the thinking of an otherwise perfectly rational thinking people of Gujarat.”

Ashis Nandy, one of the leading academics in India, met Modi in the 1980s, before Modi was known nationally. In a moving essay, he writes of meeting Modi: “I came out of the interview shaken and told Yagnik that, for the first time, I had met a textbook case of a fascist and a prospective killer, perhaps even a future mass murderer.”

As Modi prepares for next year’s national elections, he would prefer that the public focus on Gujarat’s 10.1 percent growth rate, comparied to India’s 8.3 percent. To Modi’s credit, growth has accelerated during his administration. Poverty is also lower: Gujarat has an urban poverty rate of 18 percent, compared to the national average of 21 percent. But when we examine Gujarat’s Muslim population, the numbers are less rosy. According to the New York Times, “42.4 percent of the Muslims in urban Gujarat are poor, compared with 33.9 percent of Muslims in urban India overall.”

However, poverty in Gujarat is of little importance to most Indian voters. What matters to them is whether Modi will make them rich. India’s middle class continues to boom, after all, and its annual per capita income has nearly tripled from $530 in 2003 to $1600 today. These are the voters who have embraced Modi most.

But a Modi victory next year appears mathematically impossible, given that Modi will unlikely be able to carry states with large minority populations. After the BJP selected Modi as their national leader, several within the BJP coalition broke off and began criticizing Modi, including Nitish Kumar, the popular chief minister from the state of Bihar, a state with a large Muslim population, and one that may be key for a BJP victory in 2014. In a recent article in The Indian Express, Varshney writes that Modi needs an additional 25–30 million votes to secure a victory, an unlikely proposition.

The problem, in part, is that many in the BJP see Modi as a figure who is controversial, unwilling to compromise, polarizing, and unpopular in the west. Indeed in 2005, the United States denied Modi a visa to the United States because of his role in failing to protect his citizens during the 2002 riots. It was the first time in U.S. history that a person has been denied entry based on religious-freedom violations. Even Modi’s one-time mentor, LK Advani, now views him as a liability, as someone who will continue to split the BJP and alienate a minority voter base.

But these concerns have not stopped Modi from crisscrossing across India to sway voters. This past week, Modi flew to the flood-affected state of Uttarakhand and personally rescued 15,000 people, earning him the nickname “Rambo.” Modi’s mission may have television pundits laughing but it has only cemented his popularity among India’s youth, who see him as a politician unafraid of cutting to the front of the line to get things done. After all, India’s youth see the alternative to Modi as the Congress’ Rahul Gandhi, the 43 year old the son and grandson of Indian prime ministers, and a person coddled since birth in government-funded palaces.

This past December, a week before the Gujarat elections, I appeared on an Indian TV show in Ahmedabad and spoke critically about Modi’s rule. Many in the audience came up to me after and objected to my comments. “Modi is a stud,” a young man told me. Several women said they have a crush on him. One young woman even called him “sexy.” A few even had t-shirts with Modi’s face. He is cool, many told me. This, and not a Modi-ruled India, may be more troubling: there is a generation of youth today who want, more than anything, to be like Modi.

But Modi will have to do more than rescue people from a flood or convince people that he is stylish to become prime minister. He will have to prove that he can change. But can he? The answer, Mukhopadhyay suggests, may lie with Bipin Chauhan, Modi’s tailor. Modi is known to be fashion-conscious and often changes his India kurta, or traditional shirt, several times a day. When asked about Modi’s favorite color, Chauhan says, “Modi actually does not ever wear green”—the color associated with Muslims—and prefers to wear saffron, the orange-yellowish color of the BJP and the Hindutva ideology. But these days, Chauhan says, Modi prefers to wear more muted shades, “silent” variations of saffron.

The challenge ahead of next year’s elections is for Modi to convince Indians that he is wearing a new garb. But it may be too late. Many in India, including Mukhopadhyay I suspect, have already been convinced that it is Modi’s heart—not just his shirt—that is saffron.