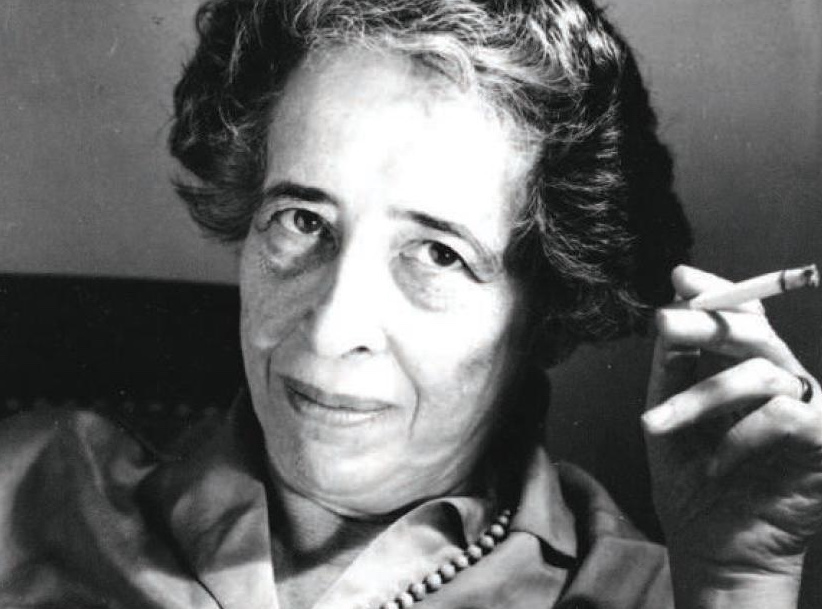

Born a Jew destined to endure the catastrophe of Nazi Germany, Hannah Arendt experienced firsthand the despair inflicted on an entire civilization when the country of her birth consumed a continent in its determination to rule the known world. She saw, up close, something in the human condition writ large that shaped her intellectual talent for the rest of her life. The experience made Arendt a political thinker.

She’d thought of herself as a Jewish German, not a German Jew. When the Nazis came to power, however, and friends, colleagues, and neighbors scrambled to forget they’d ever known her, the transformation of her identity stunned her and the question of how it had come about became an obsession. True, political gangsters had hijacked Germany; but very quickly, it seemed, other European nations had adopted an equally open policy of official anti-Semitism, as though they’d only been waiting for the opportune moment. Why? And why now? The conviction among the Jews themselves that they were, as ever, only the regulation victims of the newest barbarians did not satisfy. For Arendt, this was an inadequate explanation for the immensity of what was happening.

The Jews, she knew, had for centuries accepted routine European anti-Semitism as a given, one that naturally precluded all worldly concerns except that of survival. Now, Jew hatred had evolved into a political policy that forbade even the right to survive. She was persuaded that these elements were fused; the one, she came to believe, had not in fact been possible without the other. From there to the conviction that political freedom comes only with political responsibility—it’s either earned or forfeited—was one easy step.

The Jewish Writings is a collection of Arendt’s articles and essays written between 1932 and 1966. For this reviewer, they come as a revelation. I had never understood, exactly, the mental road Arendt traveled to get to the pronouncements for which she has been both celebrated (the reality of men trumps the concept of Man), and damned (evil was ordinary; the Jews were to be held accountable). To read the book straight through is to see clearly the origin and steady development of the single critical insight that informed much of Arendt’s subsequent work: namely, that the world is what we ourselves make it. The need to breathe free is a given; the right to do so is not. Among human beings, the will to power is an embodied force that continually challenges the right of those not like ourselves to occupy space. Under no condition is the one-not-like-oneself free to ignore the challenge. What’s more, the challenge must be resisted in the terms in which it is flung down. As Arendt put it, “When one is attacked as a Jew one must respond not as a German or a Frenchman or a world citizen, but as a Jew.”

The Jewish preoccupation with simple survival had led to a peculiar kind of worldlessness (Arendt’s word). Jews as Jews had long accepted the absence of all political action in their lives, adapting themselves skillfully to whatever circumstance was available to them, with the single shared intent of living as though gentiles did not exist. As that came down to the pursuit of either religiosity or money-making, the mass of Jews lived in shtetl obscurity practicing a self-mesmerized worship of God’s Law, while a few grew wealthy enough to bankroll the kings and ministers in whose regimes they had neither influence nor interest. This lack of worldly involvement led religious and secular Jews alike to embrace the naive conviction that Jews were outside of history (what Arendt means by “worldlessness”) and therefore—though they might be harassed, restricted, and even murdered—would essentially be ignored. When the Nazis rose to power in Germany, charging a Jewish world conspiracy with bringing about the Weimar Republic’s miseries, they were thunderstruck but greeted the accusation as no more than another chapter in the familiar history of anti-Semitic scapegoating.

What the Jews had failed to understand, Arendt now thought, was that there is no such thing as absenting oneself from history. If one is not an active participant in the making of one’s world, one is doomed to be sacrificed to the world in which one lives. At all times, agency is required. To not exercise agency is, inevitably, to be enslaved by those who do exercise it. The former condition, in fact, stimulates the latter.

It was the acceptance of the unacceptable that Arendt now considered a crucial contribution of the Jews to their own undoing. That they had gone on living for centuries motivated only by the desire to protect their backs and shield their faces had increased the enmity, among governments and individuals alike, of those who saw in such meekness everything they feared and hated in themselves, if not in human existence. The Jews never realized that what had been required of them was militant struggle against their subordinated status; without such struggle they were destined to remain social pariahs, integrated into Europe’s economic life but actively despised within its culture. Here was a dramatic illustration of the inborn human impulse to bully, squash, destroy that which is cowed into subordination. In our own time we have seen the liberationist movements of persecuted blacks, humiliated gays, and discarded women take the historical lesson: when politically despised, you either fight on your feet or die on your knees.

Many of the pieces in this book were originally published in Aufbau, a New York–based German-language newspaper for which Arendt wrote between 1941 and 1950, and they give us a Hannah Arendt many of us did not know existed: urgent, eloquent, advocating. One of the most recurrent elements in the book, for example, is her passionate insistence, throughout the war, that the Jews of the world should mount their own army and fight Hitler with guns in their hands and righteousness in their hearts. She meant this literally. There were, of course, Jews fighting in the armies of all the allied forces—American, British, Russian—but that was not the point. The Jews had to fight Hitler under their own flag. “We must enter this war as a European people,” she said, “who have contributed as much to the glory and misery of Europe as any other of its peoples.” If the allied forces defeated Hitler for the Jews, it would do the Jews as a people no good at all because “from the disgrace of being a Jew there is but one escape—to fight for the honor of the Jewish people as a whole.” Interestingly enough, an underground Polish newspaper tipped its hat to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising with these words: “The passive death of Jews had created no new values; it had been meaningless; but [this] death with weapons in hand can bring new values into the life of the Jewish people.” In mid-20th century, it transpired, one earned the right to live in much the same way as one had when crouching in a cave.

Perhaps the most important running theme in these pieces is that the Nazi assault on the Jewish people was a major setback for Western civilization as a whole: Hitler’s war had reduced to spiritual rubble modernity’s 150-year effort to honor the rights of individual human beings more than those of the state. Arendt was to consult this insight, written on her skin, for the rest of her life. In 1942 she wrote that German destruction of the European world of nations had begun with the destruction of the German nation itself, “which has perished in the infamy of Dachau and Buchenwald.” The same, she said, went for France: “When Petain put his signature to the infamous paragraphs of the French-German armistice, which demanded that every refugee in France be handed over to the Nazis, [he] tore the tricolor to shreds and annihilated the French nation.” What was left in each country, she said, was only a shattered people battling for mere animal survival, having lost most of what made life worth living. (Reading these words today, feeling as millions of Americans do about their own country, I find it painful to reflect on how much people long to believe in national honor and decency, and how great a political need that longing addresses.)

Arendt turned Jewish persecution on its head and demanded Jewish resistance not for the sake of the Jews alone, but for that of the entire modern world. In support of this position she invoked the words of the French Zionist Bernard Lazare, who, living in France during the Dreyfus period, had urged Jewish rebellion against pariahdom because it was “the duty of every human being to resist oppression,” not for one’s own good but for the good of all mankind. (She might also have invoked Gandhi who, at the height of his iconic struggle for Indian independence, wrote in his journal: “The very right to live accrues to us only when we do the duty of the citizenship of the world.”)

This idea of responsible world citizenship became key for Arendt. It led her to the passionate conviction that the sovereign state must come to an end, as nationalism in the 20th century had, clearly, proved itself the enemy of humanity. The state, she thought, should give way to federated commonwealths, each composed of a system of local governments—townships, councils, soviets—within which majorities and minorities would no longer be accorded differential rights. Such a system would facilitate the grassroots practice of direct democracy, whereby “freedom will consist of political action among equals.” A utopian vision, no doubt, but one held by social revolutionists like the anarchists, who had repeatedly made use of the vision to think hard about what human beings need to feel human.

The idea of a Jewish state appalled her. She had considered Palestine a homeland for the Jews but never advocated carving out Jewish sovereignty at the expense of the Arabs already living on the land. For Arendt, first-class citizenship for Jews and second- class for Arabs was a horrifying prospect. She could not believe that the Jews were going to do to others what had been done to them—that the pariah-turned-rebel of whom she had dreamed would emerge from hell not a statesman-like sage but a nationalist and a terrorist—and she opposed the formation of Israel from day one. This opposition took her to a place in her mind she had never imagined occupying.

In 1950 Hannah Arendt, who had spent so many years writing out of Jewish despair, wrote: “The Jews are convinced that the world owes them a righting of the wrongs of two thousand years and, more specifically, a compensation for the catastrophe of European Jewry which, in their opinion, was not simply a crime of Nazi Germany but of the whole civilized world. The Arabs, on the other hand, reply that two wrongs do not make a right and that no code of morals can justify the persecution of one people in an attempt to relieve the persecution of the other.” Throughout the war, speaking as a Jew among Jews, Arendt had consistently written “we Jews.” From now on, when writing about the Middle East, she would refer to both parties as “they.” She was still passionate about the Jews—“the wrong done by my own people grieves me more than wrong done by other peoples”—only now the passion, instead of glowing red hot, burned like dry ice. Many of the things Arendt said in the ’50s and ’60s she had, in fact, said before, but the way she now framed them seemed to leave the Jews themselves behind. And very shortly, many Jewish readers returned the compliment.

The publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1963 brought down on her—from nearly every quarter of the Western world—the open charge of Jewish self-hatred. The chief complaint against the book was Arendt’s unsentimental account of the wartime European Jewish Councils’ misguided attempt to buy time by co-operating with the Nazis and helping to draw up lists of people destined for deportation to the camps. Ironically, in 1937 Arendt had written, “It seems to me that our political and spiritual leaders have done almost irreparable damage, [clouding] our vision of the larger historical context in which we stand, and into which we are dragged deeper and deeper day by day.” This, she had added, was tantamount to signing one’s own death warrant—a thing one must never do. At the time, patriarchal Jewry received these admonitions as though coming from an overly critical daughter whose loyalty it nonetheless desired. In 1963 the remoteness in Arendt’s voice made clear that she invoked the Jews to illustrate concerns that went far beyond the subject of Jewry—and it was her head that was wanted. Among those who objected forcefully to the book was the Israeli scholar Gershom Scholem, who wrote Arendt a much-publicized letter complaining bitterly of the book’s coldness, and accusing her of having “no love of the Jewish people.”

It was true, she replied: she had no love of the Jewish people. She had, she said, never loved “any people or collective—either the German people, nor the French, nor the American, nor the working class or anything of that sort.” She had loved her friends; the only kind of love she knew was that for persons. As for being Jewish, she went on, the one thing that did matter to her—and mattered vitally—was that being a Jew had been a given of her life. Not only had she never wished to be anything else, but being Jewish had made her appreciate, as nothing else could have, the significance of being allowed to be what one is: “There is such a thing as a basic gratitude for everything that is as it is: for what has been given and not made.”

This regard for the givens of individual human existence had led her to think deeply about everything she had thought mattered during the previous thirty years. What she loved was the experience of the Jewish people: it had taught her how to consider the human condition at large. How much more Jewish did she have to be?