Another presidential election is approaching, and the outcome will have real policy consequences. A Romney victory in November, for example, could be worth more than $200,000 per year in tax savings for the wealthiest 1 percent. Yet Americans tend to be woefully uninformed of the policy positions of candidates and their parties.

For example, more than 45 percent of Americans do not know which major party is more supportive of raising the minimum wage or capital gains tax rates. But even if they cannot map their opinions onto party platforms, many of these potential voters do have opinions on the issues. Moreover, those with less knowledge of the parties hold more liberal views on economic issues than those who are better informed. Of those citizens who do not know the parties’ positions on capital gains tax, 77 percent believe that capital gains should be taxed at the same rate as regular income—or higher. Only 58 percent of more informed citizens share this view. Conversely, these less informed citizens hold more conservative views on moral issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage than do better informed counterparts.

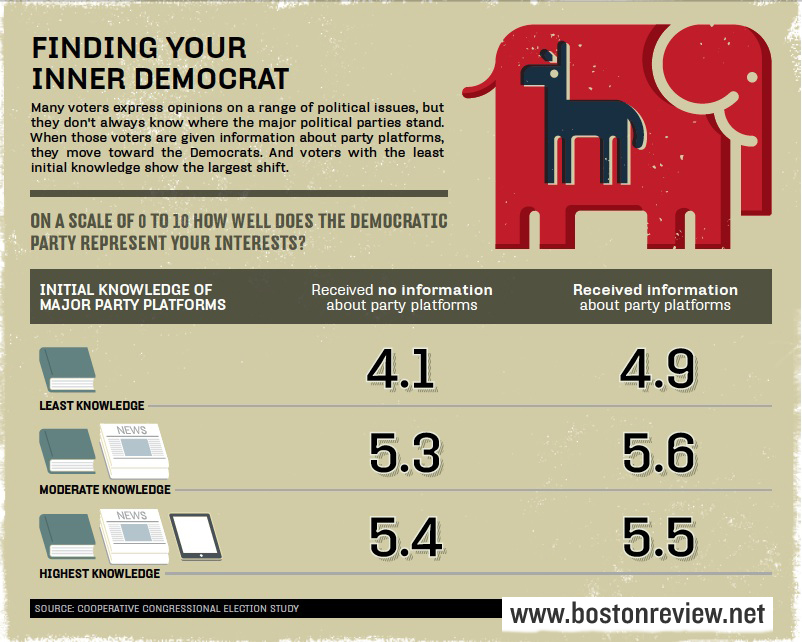

What, then, would a more politically informed America look like? To find out we ran a series of experiments that randomly assigned eligible voters to either of two groups. In one group we explained the parties’ positions on a range of issues including the minimum wage, capital gains tax, unemployment benefits, abortion, same-sex marriage, and gays in the military. In order to ensure that we were getting robust results, we varied the information provided, the sample of voters, and the method of delivery sometimes the information came embedded in newspaper articles and sometimes it was provided as straightforward fact. We then asked respondents to rate how well the parties represent their interests on a zero-to-ten scale. Across the experiments, we find that providing more information about party positions pushes the electorate toward the Democrats. This effect is especially pronounced among people who had low levels of political knowledge before the experiment. Voters uninformed on party positions who received information increased their evaluation of the Democratic Party by 0.8 points and decreased their evaluation of the Republican Party by 1.4 points, relative to the control group that received no information.

The result makes sense. Voters with little knowledge of the parties are poorer, younger, and more likely to be unemployed than are their better-informed counterparts. They’re also more likely to be members of an ethnic minority. This bloc tends to align with the Democratic Party on economic issues—once it knows where the Party stands. Their more conservative bent on moral issues is outweighed by liberal economic values, a result consistent with recent research on driving factors in voting decisions.

In the short run, a more informed electorate very well could influence election results. And in the long run, more information can change the nature of politics altogether. Citizens ignorant of the true nature of their political options cannot be adequately represented. But, empowered with knowledge, these previously under-represented citizens will be able to encourage government to act on their preferences.