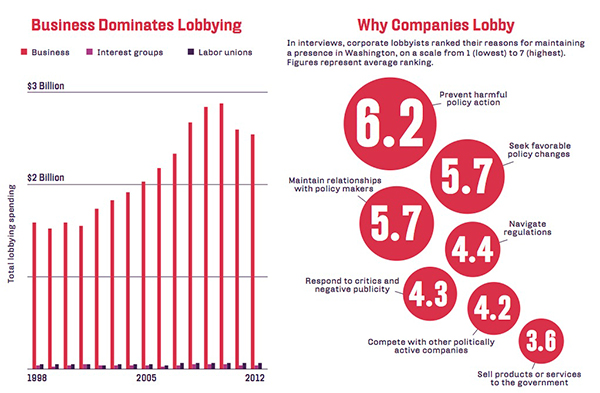

Click here to enlarge. Interest groups refers to groups that represent diffuse interests like citizens, consumers, and taxpayers. Illustration Frank LeClair.

In 2003, when Congress passed the Medicare Modernization Act, the pharmaceutical industry cheered. The bill provided government coverage for pharmaceutical drugs. One study estimated the industry benefit at $242 billion over ten years.

Traditionally the industry opposed a drug program under Medicare. Pharma was sure it would mean bulk purchasing and thus bargaining leverage for the government. But around 2000, lobbyists came up with the idea of a Medicare prescription drug benefit that prohibited the government from directly negotiating with drug companies.

The shift speaks to the evolution of corporate lobbying in Washington: from defense to offense. Prior to the mid-1970s, few companies had Washington offices. Corporate managers had elected to stay out of politics, other than to occasionally holler, “Stop!” But a new wave of regulation over the previous decade, coupled with rising inflation and increased global competition, created a sense of crisis. So companies mobilized in large numbers, hiring lobbyists and setting up Washington offices. They succeeded in rolling back the regulatory state, lowering their taxes, and putting allies in government.

With the crisis overcome, lobbyists came up with new reasons for their companies to stay in Washington. They began to craft policy that would promote their bosses’ interests, rather than simply defend them. Thus Washington lobbying came to look more like a profit center. As one pharmaceutical lobbyist I interviewed for my new book, The Business of America Is Lobbying, told me, “Twenty years ago, you had a Washington office to keep the government out of your business, and I think people have evolved to understand now that there are opportunities, partnerships with government.”

Of course, corporate lobbyists still play plenty of defense, as my survey reveals. But companies and their lobbyists are always looking for new ways public policy can help their bottom lines. They have also come to see lobbying as a long-term proposition. They appreciate the value of relationships in Congress. Most importantly, they understand that you never know when opportunity will knock in the form of, say, a must-pass bill. Citigroup knows that. That is why its lobbyists were ready to take advantage of the spending bill passed last December, which included their handcrafted language rolling back derivatives regulations.

Despite a gridlocked Congress, large companies haven’t pulled back from Washington. They have learned it pays to stay. There is plenty to preserve—and plenty to gain.