In 2012 Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign placed 193 million phone calls, sent 18 million pieces of mail, and knocked on 14 million doors. This sort of get-out-the-vote (GOTV) effort is popular because it increases turnout. And, presumably, greater participation is good for democracy because a greater share of citizens are voicing their preferences, selecting our leaders, and influencing policy.

However, more doesn’t necessarily mean more equal. What if GOTV methods primarily mobilize citizens who are already well represented and fail to nudge the rest? Can voter mobilization make the electorate less representative than it otherwise would be?

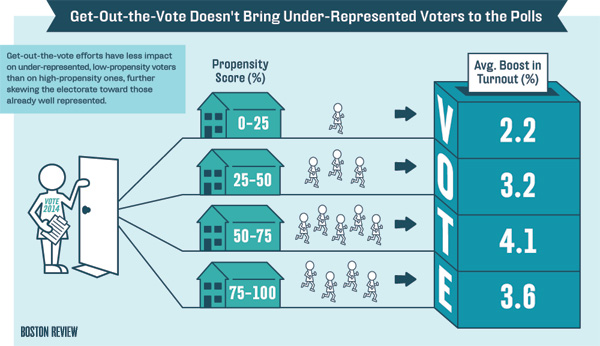

This is precisely what Ryan Enos, Lynn Vavreck, and I sought to find out in a new study published in the Journal of Politics, where we pool data on 1.2 million individuals. We used publicly available information such as age, race, gender, and geography to construct a propensity score indicating the extent to which each individual and those with similar demographic traits are represented in the electorate. We validated these scores by showing that they are highly correlated with income, education, church attendance, political ideology, issue positions, and other important political characteristics. Then we tested whether GOTV is more effective among high- or low-propensity citizens.

Because high-propensity citizens already vote in the absence of GOTV, we might expect greater effects among low-propensity individuals: there are many more of them to mobilize. However, instead of mobilizing under-represented groups, GOTV appears to increase representational inequality. In particular, voter mobilization brings more rich, white, educated, churchgoing citizens to the polls. It also contributes to over-representation of extreme views.

It is difficult to mobilize low-propensity citizens in part because they are just harder to reach. Poorer, less educated, and younger citizens are less likely to open their mail, answer the door, or pick up the phone. They also move more frequently, meaning that campaigns are less likely to have their current addresses and phone numbers.

However, contact alone cannot explain our results. Even after being contacted, under-represented groups are less likely to respond to GOTV efforts. Low-propensity individuals may be less likely to trust campaigners or so disengaged from the political process that they simply cannot be mobilized with traditional approaches.

Political scientists still don’t know how to mobilize the under-represented. GOTV practitioners and researchers should be aware that their ground campaigns are missing large subsets of their targeted voters and get creative in reaching new people. Success here could be fruitful for campaigns, and it will pay wider societal dividends. Elections that reflect the preferences of the citizenry at large, as opposed to an unrepresentative subset, create better public policy and a stronger democracy.

Illustration: Frank LeClair.