Doctors in Denial: The Forgotten Women in the “Unfortunate Experiment”

Ronald W. Jones

Otago University Press, NZ, $39.95 (paper)

In the catalog of U.S. medical research atrocities, historians customarily reserve a feature display for the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. For forty years (1932–72) researchers in the U.S. Public Health Service, working in Alabama, deceived hundreds of impoverished black men with syphilis, withholding treatment so their illness could be studied. In the years since its exposure in 1972, the Tuskegee syphilis study has become not only a powerful symbol of racism in medicine, but a case study in the exploitation of vulnerable research subjects. It is often cited as the scandal that jolted the United States into creating a formal oversight system to protect research subjects.

In fact, however, the story of Tuskegee was more complicated than the conventional narrative suggests. The federal committee appointed to investigate the Tuskegee study was handicapped by deep internal disagreements, and the chairman refused to concur with the final report. Twenty-five years passed before the federal government apologized to the victims. It took nine years for a formal system of research oversight to be instituted, and that system has not exactly been an unqualified success. Alarming reports of mistreated research subjects have continued to emerge in the United States at regular intervals for the past forty years: studies recruiting homeless people, undocumented immigrants, and involuntarily committed psychiatric patients; studies involving deception, corruption, coercion, and quackery; small-time misdemeanors involving neglect or incompetence; high-stakes medical gambles backed by powerful pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

New Zealand's response to the medical scandal should be a model for the rest of the world. Why have we paid little attention?

For a more instructive example of how to respond to abusive research, consider New Zealand. New Zealanders had their Tuskegee moment in June 1987, when Metro magazine published the investigative report “An Unfortunate Experiment at National Women’s.” According to the report, women with cervical cancer in situ had been deceived and mistreated for years at a prestigious Auckland hospital. This revelation led to an official government inquiry, six months of public hearings, and, most importantly, far-reaching reforms that have effectively prevented any further such abuses. The story of the “unfortunate experiment” and its aftermath is told in an important new book by Dr. Ronald W. Jones, an obstetrician-gynecologist at National Women’s who played a central role in exposing the scandal.

The publication of this book is a major event, and not simply because it is rare for a medical whistleblower to write with such deep knowledge and clarity. Unlike the Tuskegee study, the “unfortunate experiment” barely registered with medical researchers outside New Zealand. Even in the academic discipline of bioethics, which developed at least partly because of U.S. research abuses in the 1960s and ’70s, the “unfortunate experiment” is rarely taught or discussed.

This is a puzzling oversight. In many respects, the way New Zealand handled the “unfortunate experiment” should be a model for the rest of the world. Whistleblowers spoke out; the press did its job; the authorities investigated and said: No more. Then the government instituted reforms that have kept New Zealand medical research scandal-free for nearly thirty years. Why has the world paid so little attention?

• • •

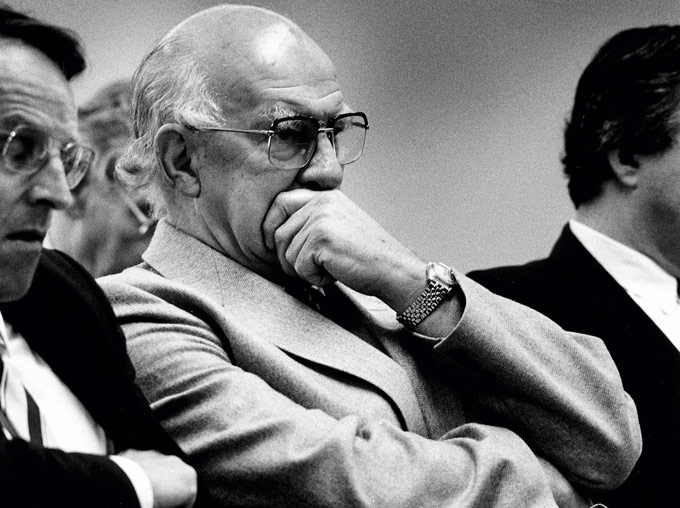

Academic physicians are not known for their modesty, but even among his peers George Herbert “Herb” Green stood out. Colleagues described him as belligerent and autocratic. “Quite a bully,” says a former laboratory technician at National Women’s Hospital. Conservative in his politics and chauvinistic in his attitudes, Green was an obstetrician-gynecologist who not only opposed abortion but also sterilization. When screening for cervical cancer became widespread, he opposed that too. Green took pride in being seen as a contrarian—a “doubting Thomas,” as he put it. His ability to intimidate others came partly from his size and bearing; Green was a large, gruff man who had grown up in gumboots on a south Otago farm. But his physical size was exceeded by his high self-regard. Green was supremely confident in his own judgment and he was not shy about letting others know it. If egos were cars, Green would have driven a Cadillac Eldorado.

In the end, he drove it over a cliff. In New Zealand Green is infamous as the physician behind the “unfortunate experiment.” His tragic flaw was signaled by a phrase written on his office chalkboard: “Don’t confuse me with the facts—my mind is made up.” Green was convinced that cervical carcinoma in situ (CIS)—a condition in which abnormal cells are found on the surface of the cervix but not yet any deeper—would not progress to invasive cervical cancer. Never mind the scientific evidence, or expert consensus, or even the policy at his hospital, all of which instructed that CIS should be treated, not simply left alone. Green’s confidence in his own judgment was unshakeable. In 1966, with the approval of his hospital superiors and all but one of his colleagues, Green set out to prove his theory to the world, allowing his patients with CIS to go untreated for years without their knowledge or consent. It would be nearly two decades before the deadly results were exposed.

This is about the systemic abuse of women: female patients at risk of cancer deceived by a powerful male doctor whose bogus research was supported by an all-male department at an institution called the National Women’s Hospital.

For years, the authoritative account of the scandal has been the Cartwright Report, the official result of the inquiry led by Judge (now Dame) Silvia Cartwright. The report laid out in exhaustive detail the rationale for Green’s experiment, the state of both medical science and ethics at the time, and, perhaps most critically, testimony from the women who were mistreated and deceived. As damning as the Cartwright Report was, it also made clear that the fault for the experiment could not be laid entirely at Green’s feet. Neither the unfortunate experiment nor Green’s unorthodox views were a secret at the hospital. If not for the backing of hospital authorities and the silence of most of his colleagues, Green could never have proceeded.

In the end, the experiment was revealed because of the tenacity of three dissenters at the hospital. In Doctors in Denial, Jones, an obstetrician-gynecologist and the last living member of the dissenting group, offers his account of the scandal. Rich in detail and heavily referenced, the book not only shows how much personal pain Jones and his colleagues suffered as they attempted to stand up for mistreated patients; it also exposes the institutional pathology at National Women’s Hospital that permitted the abuses to occur.

Jones contends that what allowed the experiment to run for so many years, despite protests, was the authoritarian hospital culture of the period, in which department heads presided over their fiefdoms like absolute monarchs and senior faculty members expected to be treated like royalty. As members of the lower ranks, Jones and his fellow dissenters were simply not taken seriously. Jones writes, “It was a time when hospitals were ruled by inflexible medical hierarchies; respect for authority, seniority and loyalty were assumed; and bullying and intimidation were commonplace.”

At National Women’s Hospital, the crown was worn by Dennis Bonham, a bald, overbearing Englishman with a Brylcreem comb-over who had beaten Green for the position of head of the Postgraduate School of Obstetrics and Gynecology. According to Jones, Bonham terrified junior staff members with his tirades. When Jones first encountered him, Bonham was screaming at a secretary while ripping apart a set of misfiled patient records. He was instrumental in approving Green’s research, squashing dissent, and stonewalling efforts to investigate.

Green was a more eccentric character. In his early days of practice, he embarked on a crusade to sterilize the stray cats on hospital grounds. Nurses would prepare a surgical tray; medical students would round up stray cats; and Green would spay them in the operating room, instructing students to kill escaping fleas with ethyl chloride. Later he became obsessed with the obstetrical tragedies of the British royalty and unsuccessfully petitioned the Queen to exhume Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII, to determine if she had had a C-section. Green could also be warm-hearted with his patients. Once, when a young woman with advanced cervical cancer was too ill to attend her graduation, Green arranged for a private ceremony in the ward, where the woman was “capped” by the university vice-chancellor. The occasion was celebrated with tea and cakes.

When Jones arrived at National Women’s as a junior specialist in 1973, Green had been conducting his “unfortunate experiment” for seven years. The purpose of the experiment was to show that CIS would not progress to invasive cervical cancer. At the time Green started his experiment, however, as Jones shows, the evidence that CIS could and often did progress to invasive cervical cancer had been mounting for decades. In 1938, researchers in Boston stopped a study early because the abnormal cells were progressing to cancer. Eighteen years later, a Norwegian study showed that 26 percent of women with CIS had developed cervical cancer within fifteen years. In 1961 a compilation of studies of untreated CIS showed an average of 28 percent of patients developing cancer. In fact, the assumption that CIS progressed to cancer underpinned the adoption of the Pap smear as a screening tool in the 1950s and ’60s. According to Neville Hacker, a past president of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society, by the time Green began his experiment in 1966 “there was almost universal agreement that CIS was a premalignant lesion.”

The conservative and chauvinistic Green took pride in being a contrarian. Displayed in his office was a sign that said: ‘Don’t confuse me with the facts—my mind is made up.’

How was CIS usually treated? According to the Cartwright Report, the appropriate treatment was to remove the lesion as soon as possible after diagnosis. In the 1950s that meant hysterectomy. But over time hysterectomy came to be seen as unnecessary and medical opinion began to favor less aggressive treatment. In 1958 National Women’s Hospital adopted a policy of treating CIS with conization (sometimes called cone biopsy), a procedure in which the physician removes the abnormal cells by cutting out a small, cone-shaped wedge of tissue around the abnormal cells. Today conization is a relatively simple outpatient procedure, but even in the 1960s, conization carried few serious risks other than a small effect on a woman’s ability to bear children (later studies indicated that conization also increases the risk of preterm births for women who become pregnant).

Green’s approach differed dramatically. As he wrote in 1970, “The only way to settle the question as to what happens to carcinoma in-situ is to follow adequately diagnosed but untreated lesions indefinitely.” So instead of removing CIS, he monitored it with Pap smears and small punch biopsies. Only when a woman developed clinically invasive cancer would she be treated. Green would eventually withhold treatment from more than a hundred women with CIS and microinvasive cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. Just how many women died as a result has never been confirmed; the Cartwright Report did not give a figure. According to Jones, Sandra Coney (coauthor of the Metro article) has put the death count at thirty, but that does not include those who have died since the Cartwright Report.

Why did Green’s colleagues let him proceed? For Jones, this is a far more disturbing question, and ultimately, a more mysterious one. Green’s proposal was not just a dangerous departure from hospital policy that could jeopardize the lives of patients. It was not even a well-designed experiment. The study had no control group, no stopping rules, no consent forms, and no data safety monitoring board. For the women under Green’s care, there was a lot to lose and little to gain apart from being spared the discomfort of conization. That Green was departing from standard procedure was no secret to anyone. Green’s colleagues all treated their private patients in accordance with hospital protocol—that is, with conization. Yet not only did they say yes to Green in 1966, they also ignored the warnings of the hospital’s dissenters when Green’s subjects began to get cancer.

When Green started his experiment, the only physician to object was a self-effacing, gentlemanly Presbyterian named Bill McIndoe. As the hospital specialist in colposcopy and cytology, McIndoe examined every patient with an abnormal Pap smear, including Green’s, and read the follow-up smear tests. Convinced that Green’s misguided approach would harm patients, McIndoe prepared a memorandum opposing the experiment and spoke out against it. But McIndoe was a junior staff member without an academic appointment. He had come late to medicine after training as an electrician. As an attorney at the Cartwright Inquiry later put it, McIndoe’s objections were “equivalent to the office boy trying to tell the managing director how to run the firm.”

As the experiment progressed, however, the soft-spoken McIndoe acquired an ally. Jock McLean was an unpretentious, well-trained pathologist from a working-class background who, like McIndoe, spent his days looking through a microscope. McLean could see firsthand the slow, creeping spread of untreated CIS in Green’s patients, sometimes even moving beyond the patient’s cervix to her vagina and vulva. In 1973 he joined McIndoe in submitting formal memoranda to hospital authorities protesting Green’s misguided approach to CIS, complete with scientific documentation and the names of mistreated patients. Yet the only response they got was stonewalling, righteous indignation, and, nineteen months later, a whitewashed investigation affirming Green’s personal and professional integrity.

By 1978 McIndoe had become deeply frustrated. It was clearer than ever that Green’s patients with CIS were getting cancer. Visiting experts and new staff members were baffled as to why CIS patients were not being treated. In addition McIndoe had discovered that Green was altering the pathology reports of some subjects in order to get better results for his study. (The Cartwright Inquiry would later find that Green had also manipulated data in his published reports.) Eventually McIndoe decided to make a presentation at a major international conference in Florida. He did not mention Green by name but simply gave the long-term outcomes for over a thousand women with CIS. The results showed that CIS had invasive potential and that many subjects with untreated CIS had gone on to develop cervical cancer. That was enough to attract the attention of the editor of the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology, who immediately invited McIndoe to submit his study. McIndoe agreed and invited McLean to be a coauthor, but they struggled to put the paper together. It would take six years of work—and eventually the crucial addition of Jones, a younger man, as a catalyst—before the paper would appear in print.

What allowed the experiment to run for so many years, despite protests, was the authoritarian hospital culture of the period, in which department heads presided over their fiefdoms like absolute monarchs.

Jones and his fellow dissenters assumed that the publication of their 1984 paper would be like a bomb going off. Instead, the paper was met with utter silence. Jones writes, “It seemed incomprehensible to us that no one said anything.” Yet that is exactly what happened. There was no response from the authorities at National Women’s Hospital, no response from hospital colleagues, and no response from the wider medical community. The attitudes of senior physicians at National Women’s toward the treatment of CIS did not change in the slightest.

However, in time their article found its way to Phillida Bunkle, a women’s studies lecturer at Victoria University in Wellington, and Sandra Coney, a freelance journalist and feminist activist. The women commenced their own investigation and, in June 1987, the report of their findings appeared in Metro. The phrase “unfortunate experiment,” which gave the story its title, was taken from a 1986 letter by David Skegg, an internationally recognized cancer epidemiologist who had criticized the study in the New Zealand Medical Journal. Anchored by the personal story of one of Green’s subjects, later identified as Clare Matheson—who, in the first paragraph, recalled telling friends that an appointment at National Women’s felt like a visit to Auschwitz—the Metro article was impossible to ignore. The New Zealand government acted with remarkable speed. On June 10 the Minister of Health announced a public inquiry to be led by Judge Silvia Cartwright. Less than two months later, the Cartwright Inquiry had begun.

• • •

Like low-budget horror movies, medical research scandals tend to follow a predictable script. The ambitious researchers are blinded by hubris, while the research subjects are vulnerable and powerless. Medical insiders are aware of the abuses taking place, but few speak out. If they do, they are crushed by functionaries in suits whose only concern is protecting the reputation of the institution. Eventually the research abuses come to light, at which point the audience gasps and wonders: How could this have possibly happened?

Perhaps the most demoralizing aspect of medical research scandals is the backbreaking effort it takes to get them stopped. The United States Public Health Service kept the Tuskegee experiment going in plain sight for a full forty years. It took seven years for Peter Buxtun, a young employee, to convince anyone that the experiment was unethical. Whistleblowers at other institutions have had to agitate for even longer. The twenty-two years that elapsed between McIndoe’s initial protest against Green’s experiment and the publication of the Cartwright Report in 1988 may seem excessive, but the stonewalling and delays faced by McIndoe and his allies are the rule rather than the exception.

What does mark the unfortunate experiment as unusual is the effectiveness of the Cartwright Report when it finally came. It is rare for the exposure of research abuse to trigger any deep or sustained public reaction, much less lasting reforms. Many scandals vanish from public consciousness within days and leave no trace. Yet the Cartwright Report was earthshaking. Jones estimates that it “had more impact on the practice of medicine in New Zealand than any other single event.”

Not only did Cartwright Report validate the concerns of the National Women’s Hospital’s dissenters, it uncovered even more jaw-dropping abuses. For instance, it revealed that as part of the hospital teaching program, physicians and trainees had performed vaginal exams and procedures on anesthetized, unconscious women without their consent. Defending the practice, Bonham explained that asking permission from the women would have been too time-consuming and expensive. That explanation did not play well publicly. The Human Rights Commissioner called the practice a “form of rape,” and the Minister of Health ordered hospital boards to make sure the practice was stopped.

Like low-budget horror movies, medical research scandals tend to follow a predictable script. The audience gasps and wonders: How could this have possibly happened?

The report also revealed that Green had ordered nurses to take vaginal smears from 2,200 newborn baby girls without informing the parents. Why? Green was trying to gather evidence for his theory that CIS was a benign condition that was sometimes present in infant girls at birth. At another point, the inquiry learned that, in 1972, Green had begun yet another experiment called “the R series.” The purpose of “the R series” was to determine which of two treatment for Stage 1 or 2 cervical cancer was better, radiation alone (internal and external) or internal radiation plus surgery. Once again, Green “enrolled” subjects in the experiment and randomized them to one of the two treatments without their informed consent—indeed, without their awareness. The women were told that the most appropriate treatment had been chosen for them. They had no idea they were in a research study.

Just as shocking was the testimony of many of the hospital’s patients. “I loathed and detested being a patient and going through the clinic,”one woman said. She had been given a cone biopsy without her consent and would have never known had she not secretly looked at her medical file when her doctor was out of the room. Another woman said she was treated like an “animated cadaver.” Yet another said that after she had undergone treatment for invasive cancer, “I woke up from that anaesthetic screaming, absolutely screaming. I was out of control because I was in so much pain. It was like waking up to torture.” A cesium rod had pierced the wall of her cervical canal. Doctors never told her what happened. She did not learn the truth until the inquiry.

In a just and righteous universe, the Cartwright Inquiry would have been a triumph for McIndoe, McLean, and Jones. Yet Jones remembers it as a pyrrhic victory. By the time the inquiry began, Jones’s wife had been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. Bill McIndoe had died unexpectedly of a heart condition. Former friends and colleagues had turned against Jones, and the fact that he was proven right did little to change their minds. Jones writes, “My friend, mentor and supporter, McIndoe, was dead; my wife, Barbara, was likely to die; I had a young family about to be motherless; and I was persona non grata among my colleagues.” Is this what moral victory looks like?

• • •

In the decades since the Cartwright Report, Jones has become one of its most prominent medical defenders. That such a defense should be necessary is not a shock; it would have been much more surprising if a medical culture as deeply entrenched and authoritarian as the one Jones describes had fully embraced the changes recommended by the report. Yet even critics of the Cartwright Report do not generally dispute that its recommendations have kept research subjects safe. In the nearly thirty years since its publication—a period that has seen stunning abuses of human subjects in other countries by pharmaceutical companies, contract research organizations, and major research universities—New Zealand has not experienced a single major research scandal. What accounts for its success?

One likely reason is simply the nature of New Zealand, a small country with only two medical schools. An egalitarian, socially progressive society that provides universal health care for its citizens, it does not have the impoverished, easily exploitable underclass of the United States. Its universities are publicly funded, and its medical researchers have not been subject to the social and legislative measures that have transformed U.S. universities into competitive, quasi-corporate organizations. As a result, the potential threats to research subjects are probably less severe in New Zealand than they are in many other parts of the world.

One woman said she was treated like an ‘animated cadaver.’ Another likened her experience to torture.

Yet part of the success has no doubt also come from the sensible structural reforms recommended by Cartwright. Today medical research in New Zealand cannot proceed without formal approval by one of several regional Health and Disability Ethics Committees, which, unlike most of their U.S. counterparts (institutional review boards, or IRBs) are independent of the institutions in which research is taking place. The members of these committees are appointed not by research institutions, as in the United States, but by the Ministry of Health. (In their early days, half of committee members had to come from the lay public, although that requirement has now changed.) Unlike IRBs, which operate in private, the meetings of the Health and Disability Ethics Committees are open to the public, and their minutes are posted on the Internet.

Another reform was the establishment of the Office of Health and Disability Commissioner, which is empowered to investigate the complaints of patients and research subjects, as well as a legally enforceable Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights. Again, these developments set New Zealand apart from the United States, where research subjects with complaints face a bewildering patchwork of oversight organizations with differing responsibilities, from the Office of Human Research Protection to the Food and Drug Administration to individual IRBs.

Yet many observers believe that the most significant result of the Cartwright Report has been the profound changes in social attitudes. Doctors are no longer encouraged to regard themselves as minor deities, and patients now demand a much greater role in making medical decisions. While those changes may have eventually come to New Zealand anyway, as they did elsewhere in the world, the force of the blow dealt by the Cartwright Inquiry would be hard to exaggerate. It was not just that alarming revelations were reported on national television for six months, or that the abuses took place in one of country’s most respected institutions. It was that the abuses extended well beyond a single research study. Women all over New Zealand could imagine themselves and their daughters as the potential objects of mistreatment.

Of course, the impact of the Cartwright Inquiry was also buoyed by a larger social transformation. What the exposure of the Tuskegee study did for the cause of civil rights in the United States, the exposure of the unfortunate experiment did for the cause of women’s rights in New Zealand. If you were looking for a vivid illustration of the systematic mistreatment of women, you could hardly do better than a six-month televised investigation of female patients at risk of cancer being deceived and exploited by a powerful male doctor, whose bogus research was supported by an even more powerful male administrator, and which was conducted in an all-male department—all at an institution named the National Women’s Hospital.

This is not to suggest that the Cartwright Inquiry faced no resistance. In March 1989, less than a year after the inquiry had finished, a Wellington newspaper published a report with the headline “Cartwright Report based on a scam.” That was soon followed by a Metro article, “Second Thoughts on the Unfortunate Experiment,” in which staff writer Jan Corbett characterized Green as the “victim of a well-orchestrated smear campaign” and Coney as a “feminist lobbyist” with a “well-documented loathing of male doctors.” Even today, the findings of the Cartwright Report are sometimes disputed, largely because of a revisionist account of the scandal by Auckland University historian Linda Bryder, who in 2009 defended the experiment in her book A History of the Unfortunate Experiment at National Women’s Hospital. In 2012, describing Green’s experiment as a “careful and open study” and the Cartwright Inquiry as a “mixture of farce and tragedy,” Cambridge University medical researcher (and New Zealander) Robin Carrell asked, “How does an enlightened nation descend into irrationality and allow witch-hunts to destroy the lives of decent people?”

No one familiar with the history of medical research scandals will be surprised by this backlash. Some Public Health Service researchers defended the ethics of the Tuskegee study for the rest of their lives. But it is hard to see any sound ethical ground on which to defend Green’s experiment. Today nobody disputes that cervical carcinoma in situ can progress to invasive cancer. Nor does anyone dispute that it should be treated immediately. Even in 1966, Green understood that the great majority of his professional colleagues would see non-treatment as dangerous. Otherwise it is hard to see why he would have felt compelled to tell his colleagues that his “conscience is clear” and that he accepted “complete responsibility for whatever happens.”

The revisionists claim that Green’s unorthodox views on CIS were not as far out of step with the prevailing standard of care as the Cartwright Report suggested. But even if this were true (the case is dubious) there is no way to justify the sloppy design of his study, his manipulation of research data, and—most damningly—the absence of any consent whatsoever from his research subjects. By 1966 it had been nearly twenty years since the development of the Nuremberg Code, a foundational research ethics document that begins with the statement, “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.”

Unlike the private investigation into the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, the New Zealand scandal was televised, requiring Green and the hospital to defend their actions in public.

Despite its title, Doctors in Denial is not a fiery indictment of the medical profession. Jones writes with decency and humility, and, in the light of the way he was treated, a remarkable absence of bitterness. Any anger is directed toward the authorities who turned a blind eye to the scandal for years and the revisionists who have tried to distort the record. If anything a kind of sadness runs through the book, a sense of regret that exposing the scandal meant destroying the reputation of National Women’s Hospital.

Yet perhaps some kind of destruction was necessary. One of the most galling aspects of the Tuskegee syphilis study and the other notorious U.S. research scandals of the 1960s and ’70s is how negligible the consequences were for the researchers involved. Not only did they face no sanctions; in many cases, they went on to receive honors from their peers. Any positive social effect that might have come from the exposure of the scandals was undercut by a larger message: no matter what medical researchers do to their subjects, they will be protected.

The Cartwright Inquiry sent a radically different message. Unlike the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, which met privately, the Cartwright Inquiry required Green and Bonham to defend their actions in public. Neither man performed well. Green, looking elderly and ill, evaded questions and patronized his questioners. He was later described by an attorney as a “draught horse with blinkers on.” At the recommendation of the New Zealand Medical Association, both men were charged with “disgraceful conduct” by the Medical Council. While the charges against Green were dropped because of his poor health, Bonham was censured and fined.

As a rule, academic physicians are much better at celebrating the heroes of medicine than at remembering the uglier aspects of the past. Often abuses of research subjects are never even recorded in medical journals, much less condemned. As a consequence, U.S. research institutions—unlike those in New Zealand—seem doomed to repeat their mistakes. The habits and forces that lead to injustice and exploitation are deeply rooted. If wrongdoing is never even publicly acknowledged, it is very difficult to change.