On his way to the G20 summit in Buenos Aires held earlier this month, President Trump was asked about a key finding of his own administration’s dire climate report, which warns that climate change will cost the U.S. economy hundreds of billions of dollars, possibly up to 10 percent of GDP by 2100.

Trump replied, “I don’t believe it.”

These four words typify the president’s penchant for opting out of common sense and consensus, rejecting research and facts, preferring instead to go with his own brain, gut, or even genes. (He says he understands science because his uncle, John, was a scientist on MIT’s faculty for decades.) And, sure enough, the United States got its own clause in a G20 statement, refusing again to join the signatories of the Paris Climate Agreement in a commitment to tackle climate change.

We may not get the emergency we expect, but rather the emergency we deserve.

The same four words echo those of a character, John, in Lars von Trier’s science fiction art film Melancholia (2011). There are widespread predictions of an imminent collision between Earth and a rogue planet, but John rejects them all. Strange animal behaviors and other portents suggest the catastrophists are right, but John sees the forecasters as mere showboats. “Prophets of doom,” he calls them. Worse yet, fake news: “They’ll write whatever they can to attract attention.” Invoking his own preferred scientists, John forecasts a near miss. Looking up at the sky through his own very large telescope, John reassures his panicked wife and anxious son that the dire predictions are belied by what he can see with his own eyes. Don’t look at the Internet, he tells his wife. Trust me. Tracking the rogue planet’s movement, John says again and again, “no collision”—as if repeating it will make it true.

Wealthy, with a remote estate sporting a private road and its own golf course, John has all the confidence of a man insulated from the harms that affect the rest of us. His habituation to private privilege is evident when his butler, an older man named Little Father, cleans up John’s messes only moments after he makes them. Unsurprisingly, then, when John realizes he has erred in his calculations, he seeks out a private escape: he takes the sleeping pills his wife has been hoarding for their son and abandons his family, leaving them—on their own and wide awake—to face the implacable certainty of world destruction.

The New Zealand Plan B is not for caravans from the south nor for millennials headed north; it is for Gulfstreamers and one-percenters.

The Johns of the world today, many of whom have benefitted from the work or largesse of their own little fathers, surely have ample supplies of sleeping pills, to be used in the event of catastrophe. But they are also turning to other escapes. Over the last two years several Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have bought multimillion-dollar doomsday bunkers from a Texas company for use in New Zealand. (The company’s slogan: “We don’t sell fear. We sell preparedness.”) “At the first sign of an apocalypse,” reports Bloomberg News, “the Californians plan to hop on a private jet and hunker down.” Said former Prime Minister of New Zealand, John Key, “There comes a point at which, when you have so much money, allocating a very tiny amount of that for ‘Plan B’ is not as crazy as it sounds.”

Who doesn’t want a Plan B? Asylum seekers certainly do, and they act accordingly when they take to the road seeking refuge elsewhere. Millennials do, too, according the New York Times, which reports rather breathlessly on those who are buying land in the Catskills, Oregon, and Vermont—places least likely to experience extreme weather in the coming years: “They are following in the footsteps of billionaires like Peter Thiel, who is investing in real estate in New Zealand in case a climate apocalypse occurs.”

But the New Zealand Plan B is not for caravans from the south nor for millennials headed north; it is for Gulfstreamers and one-percenters, wealth-migrants such as Thiel with money enough to buy New Zealand citizenship, land, private jets, and a Texas-made bunker or two. In a world of opt-outs, however, nobody’s edge is permanent, not even that of the super-rich. One day, some wealth-migrants may be stunned to learn that New Zealand is just a poor man’s Mars.

• • •

The presidency comes with a Plan B of its own (though Trump, who has called the White House “a real dump,” may find it wanting). According to Elaine Scarry’s Thinking in an Emergency (2011), one of many presidential bunkers lies in the mountains of Virginia: “a man-made cavern large enough to contain three-story buildings and a lake—‘a lake,’ as one journalist observed, ‘large enough for water-skiing.’”

Aside from the presidential Plan B, the United States does little to prepare for emergencies.

But aside from the presidential Plan B, the United States does little to prepare for emergencies. We have phone alerts and emergency broadcast signals, earthquake and fire drills in schools, but there are no detailed state or federal government plans that we all know of for orderly evacuation or shelter provision. Last January, when residents of Hawaii received phone communications stating that there was an incoming ballistic missile threat, residents were advised simply to “seek immediate shelter.”

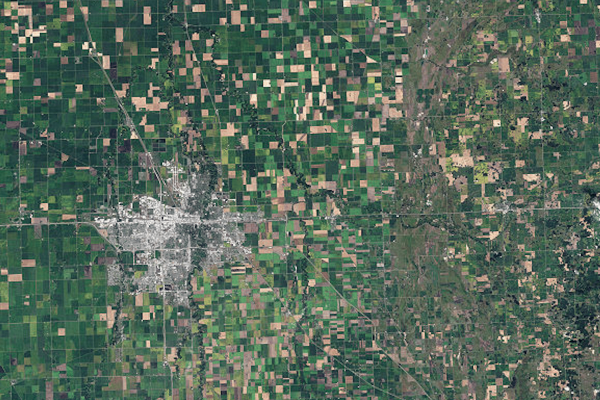

By contrast, Scarry points to certain communities in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, which have regular emergency drills and reviews of billeting and supplies to prepare everyone for emergencies. These preparations do still more: they also habituate people to thinking and acting like a public, with shared concerns, responsibilities, and attachments to public things and purposes. The lack of emergency infrastructure in the United States leaves us on our own, to fend for ourselves. The majority of Americans may not be climate change deniers, but we live as if we are in denial—as if all of us, not just the current president, “don’t believe it.”

Emergency preparations habituate people to thinking and acting like a public, with shared concerns and responsibilities.

Writing in 2011, and focused on nuclear rather than climate catastrophe, Scarry contrasts the United States to Switzerland, which “has enough shelter space (including home dwellings, institutions, hospitals, and public shelters) for 114 percent of its population.” Scarry warns that if (when?) the time comes for the United States to use its presidential bunker, however, our government’s elites may meet resistance. The privileged evacuees will have badges or uniforms that mean they must be let through—to the front of a line, to get on a bus, to pass through a traffic jam, or to board a helicopter. But will the crowds part peacefully for them in the name of the public good? Unhabituated to being a “public,” attached instead to calculations of interest and personal advantage, who knows what will they do? On that day, the dependence of the opt-out on popular acquiescence, or subjugation, will be rendered starkly clear.

Scarry imagines recalcitrant crowds, but she does not consider the possibility that political leaders might simply use violence to clear the way. To her credit, she seems to find this possibility unthinkable. Sadly, Silicon Valley’s getaway artists do not. As Bloomberg reports, one prominent venture capitalist has in his garage

a bag of guns hanging from the handlebars of a motorcycle. The bike will allow him to weave through traffic on the way to his private plane, and the guns are for defense against encroaching zombies that may threaten his getaway.

“Encroaching zombies”? Is that a pet term for neighbors and fellow citizens?

There are other Plan Bs available, too. They may be less exclusive than those reserved for political and economic elites, but they remain problematic—not because of how they opt out of the public, but because of what they propose we opt into: new solar radiation management methods promise to re-cool the earth and manage climate. Such techniques seem drawn from dystopian fiction designed to teach the tragic lessons of hubris. Should we “spray sea water up out of the oceans to seed clouds and create more ‘whiteness’” in order “to reflect the heat of the sun”? Or should we “put mirrors in space, carefully located at the point between the sun and the Earth where gravity forces balance” and thus reflect up to “2 percent of the sun’s rays harmlessly into space”? Audre Lorde once warned against such techno-utopianism. “Sometimes we drug ourselves with dreams of new ideas. The head will save us. The brain alone will set us free. But there are no new ideas . . . to save us,” Lorde said, “only old and forgotten ones . . . along with the renewed courage to try them out.”

“Encroaching zombies”? Is that a pet term for neighbors and fellow citizens?

As many commentators have noted, it seems easier these days for people to imagine blotting out the sun than to imagine the end of capitalism—the growth-addicted economy that got us here and to which we seem addicted, to the bitter end. Ending capitalism, or at least moderating it, would require courageous moral and political leadership, from above and below. Instead we have scientists whose hollow assurances that they can blot out the sun “carefully” and “harmlessly” recall Melville’s Ahab in one of his madder moments: “Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

Sparring with the sun may well be the next stage of the slow violence of climate change. “It’s going to be a slow, gradual burn, if you will,” said Vivek Shandas, founder of the Sustaining Urban Places Research Lab, to the Times. New technologies may buy us more time, as the solar radiation managers promise. But the very idea of “buying time” evokes the Plan B logic of opt-outs and buy-ins that betray the democratic idea of public things. The Democrats’ current proposal of a Green New Deal, by contrast, invites us to think and act like a public invested in a public thing—climate health, yes, but also equality and American ingenuity. “This is going to be the New Deal, the Great Society, the moon shot, the civil-rights movement of our generation,” said incoming congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at a recent town hall event. The Green New Deal invites us to move away from transactional calculation and zero sum games. It dares to dream, and dream big. Writing in the Atlantic, Robinson Meyer says that the Green New Deal is a slogan “like ‘Medicare for All’ or ‘Free Community College’ or ‘Abolish ICE,’” but, like the best slogans, it is also “a worldview, a promise, and a vision of how life would be different after their passage.”

• • •

In Melancholia, the end of the world comes out of nowhere. The disaster imagined by the film is not one we have anticipated—nuclear war, climate catastrophe—but the seemingly random end of everything. It is a perversely fitting end: a rogue planet bucking the (solar) system destroys a world of rogue individuals who take pride in doing the same. We may not get the emergency we expect, the film suggests, but rather the emergency we deserve.

Joining up with others provides the power that opt-out individualism promises but can not deliver.

For those north-bound millennials who would opt out of collectivity seeking isolation and control, Bruce Riordan of the Climate Readiness Institute has some advice: “Sure, you can grow your own vegetables, but what about wheat and grains? And what happens when you need medical attention?” Shandas, too, underlines the importance of mutual dependence: “Pulling away and isolating yourself is one of the most dangerous things you can do.” Joining up with others provides the power that opt-out individualism promises but can not deliver. Old democratic ideas about equality, mutuality, the power of public things, and a shared mission are sometimes dismissed as cumbersome by climate experts who say we need change fast, but they may be the kind of old ideas that—combined with courage—will light the way.

Melancholia ends with John’s wife, son, and sister-in-law sitting inside a bare tepee, through which the impending catastrophe sounds. In his absence, the three hold hands. That may not be consolation. But it may be instruction.