As protesters demand justice for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and Ahmaud Arbery, calls for police and prison abolition have gained unprecedented traction. A majority of the Minneapolis city council pledged to disband a police department it said “cannot be reformed,” the public school system in Portland canceled its $1.6 million contract for “school resource officers,” and Los Angeles has reallocated $150 million from the police budget to communities of color.

Struggles for black freedom have always had to contend with prisons and police as the enforcement arm of the racial capitalist state.

Both critics of abolition and recent converts often frame it as a radical new concept. This can have the effect, intended or not, of making it seem idealistic, naïve, or undertheorized. But while the mainstream prominence of abolition may be new, the premise is not. Indeed, the struggle against mass criminalization—sometimes characterized as the “civil rights movement of our time” to combat a system described by some as the “new Jim Crow”—was a crucial feature of the movement to end the original Jim Crow. Struggles for black freedom have always had to contend with prisons and police as the enforcement arm of the racial capitalist state.

However, many people remain unclear about how the movements to abolish prisons and abolish police connect to each other, exacerbating the feeling that the movement to abolish police lacks a history. But the movement to abolish prisons has always understood that doing so would necessarily entail an end to policing. Without police, there would be no one to fill prisons and jails. Without prison and jails, the police could not serve their current purpose. Put most simply, the two are locked in a mutually dependent relationship: to serve capital, and protect themselves.

Historic movements to abolish prisons called for an entirely different social and economic order in which prisons and police would not exist. Considering how prison abolition was woven into the last century’s civil rights movement can help us better understand how to build on those successes in framing our own demands.

• • •

In April 1947, nine men with suitcases in one hand and overcoats in the other posed briefly for a photograph in Richmond, Virginia, before embarking on a two-week racial desegregation campaign in the South known as the Journey of Reconciliation.

“Our present way of life—with its reliance on violence in economics, in politics, in social change, and in international warfare—is a corrupt society. And prisons today are a reflection of this society.”

The men comprised an interracial group, eight black and eight white. (Women were originally set to participate but ultimately prohibited to avoid evoking fears of interracial sex.) Their aim was to test the effectiveness of a recent Supreme Court ruling, Morgan v. Virginia (1946), which overturned state laws forbidding interstate travel by integrated groups. The Journey of Reconciliation is sometimes remembered as the “first Freedom Ride,” inspiration to the better-known busloads of student activists who in 1961 set out from Washington, D.C., with the goal of driving to New Orleans and were repeatedly attacked and imprisoned along the way. By the Journey of Reconciliation’s end, the men had attempted to board twenty-six buses and trains. A total of twelve were arrested on six different occasions, and three ultimately served twenty-two-day sentences on a North Carolina chain gang. James Peck—the sole participant in both the 1947 and 1961 rides—was brutally beaten during both.

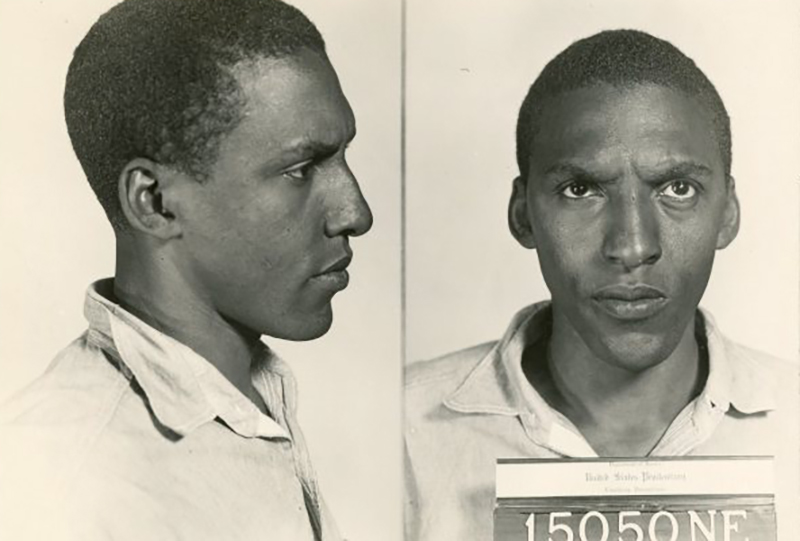

Rarely noted is the fact that, of the Journey of Reconciliation’s participants, eight were formerly-incarcerated conscientious objectors and part of a growing network of prison abolitionists. For example, Bayard Rustin, a young gay socialist who would go on to help organize Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 March on Washington, was sentenced to serve three years in 1944 for violating the selective service act. He began his prison term by singing the anti-lynching ballad “Strange Fruit” through the vents from solitary confinement at Ashland prison. He would soon lead hunger strikes against racial segregation and protesters chanting “Jim Crow Must Go.” Another participant, Wally Nelson, a black pacifist, walked out of a Civilian Public Service camp in 1943 and served three and a half years in federal prisons. There, he went on a 107-day hunger strike against racial segregation and was force-fed for 87 days until his release in 1946.

George Houser, who along with Rustin was the Journey of Reconciliation’s mastermind, had served a year at Danbury federal prison for draft resistance in 1940. In September 1945, the year before he and Rustin began planning the Journey, Houser hosted nearly fifty formerly incarcerated men at his Philadelphia home for the inaugural Conference on Prison Problems. The attendees were mostly white (federal prisons were three quarters white and many black objectors, such as Nelson and Rustin, were still incarcerated on longer sentences than their white peers); they had been imprisoned in protest of conscription, war, imperialism, and racism, and now met to theorize the intersection of these moral evils with prisons themselves. Houser, for example, noted this intersectionality when writing shortly before the conference about a hunger strike against racial segregation at Lewisburg prison (where Rustin was incarcerated). “Some of the fellows decided to make the purpose of the strike more inclusive,” he wrote. “Not only would they protest race discrimination, but also the general philosophy behind the prison system.”

At the conference, the chief debate was whether to work toward prison reform or outright abolition. While there was general consensus in the goal of abolition, the question became how to get from here to there. The group’s concrete first steps were to divorce the chaplaincy from the prison, create independent legal aid, end all censorship, and demand paid work at union wages and all time in jail to count toward sentence. A meeting later that year even proposed settling the debate by calling the organization Prison Abolition Through Reform.

While the conference did not outline a holistic plan for what would replace prisons, the participants felt that an important next step would be to “propose an alternative way of dealing with anti-social behavior.” Among the conference’s concrete suggestions, in the meantime, was to omit names from news reports of crimes (to prevent people from being stigmatized) and the creation within the criminal justice system of a “prosecutor of society” who would “present evidence as to the guilt of society” in all cases. It was also recommended to create a prisoners’ bill of rights, which would include an end to racial segregation, the right to workman’s compensation, no mandatory work without pay, conjugal visits, the right to communication with an attorney, an end to censorship, and “no solitary, no strip cell, no dark cells.”

Abolition is inherently intersectional. To unravel the punishment system is to lay bare the interconnection of people’s struggles against extraction, dispossession, and enclosure organized through racial and gendered hierarchies.

Although the conference attendees fiercely debated the relationship between reform and abolition, the pages of Grapevine, the community’s newsletter, were less ambivalent. One reader responded to the question, “What are you doing about the prison system?” by writing, “of the two groups—reformists or abolitionists—I am of the latter.” Anticipating the adage of abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore that “prisons are catchall solutions to social problems,” he went on to argue: “for as long as we have prisons and prison reforms more and bigger and better prisons will appear, as history is proving, and society will keep on using them as an escape from its own responsibilities of correcting the economic and social failures that make crime possible. Yes, reforming the prison system is like repairing a shack that should be torn down.” Newt Garver, who went to prison after burning his draft card in 1946, warned there, “Don’t get any false optimism about prison reform. Any hope there is lies outside the system, not in it.”

For his part, Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation’s other main organizer, was never an outspoken abolitionist. But early in the course of his long activist career, he did organize against both prisons and policing, beginning immediately upon his release. Just months before departing on the Journey of Reconciliation, he wrote a treatise “Imprisonment from the Inside” decrying punitive solutions to social problems:

Our aim today is to see that our present way of life—with its reliance on violence in economics, in politics, in social change, and in international warfare—is a corrupt society. And that the prisons today are a reflection of this society. . . . We must see the connection between our use of the atomic bomb in international war and our mistreatment of the offender against society internally.

Even the Journey of Reconciliation itself provided ample opportunity to challenge the carceral state. As a result of his arrest during the rides, he and two other riders who attended the Philadelphia conference—Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet—served three weeks on a North Carolina chain gang. Rustin wrote a scathing report which was serialized in the New York Post and the Baltimore Afro-American and contributed to the abolishment of chain gangs in the state.

• • •

Although abolition was not a central demand of the midcentury civil rights movement—despite informing the activism of many of its key figures—it took hold in the 1970s. This revolutionary ethos—what Chicano poet Raul Salinas called the “prison rebellion years”—was linked to mass uprisings in the streets; the state repression, jailing, and murder of black and brown radicals; and opposition to the Vietnam War and imprisonment of conscientious objectors. Quaker Fay Honey Knopp’s pivotal 1976 Instead of Prisons: A Handbook for Prison Abolitionists, for example, had its genesis in her visits to conscientious objectors in prison during the Vietnam War and her participation in feminist, civil rights, gay rights, and prisoners’ rights struggles.

As historians Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier document, prisoners became “symbols of, and spokespeople for, broader radical movements.” The 1980s and ’90s saw an emergence of international gatherings on abolition. In 1983 Ruth Morris would organize the International Conference on Penal Abolition, and the abolition formation Critical Resistance in the Bay Area was formed in the late 1990s. Other groups since then—including Incite!, Survived and Punished, Movement 4 Black Lives, BYP100, Dream Defenders, the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls—have made abolitionist praxis a core part of their visions of liberation.

The kneejerk question is often, What would we do without prisons or police? rather than, What could we do with $200 billion for our communities?

Abolition has developed and expanded dramatically since the Philadelphia Prison Group conference, thanks to the contributions of incarcerated people, black radical feminists, survivors of sexual violence, Muslims, immigrants, and queer, trans, and disabled folks, among others. Consistent though has been a commitment to fighting the racism, militarism, and capitalism that define U.S. empire. Abolition is inherently intersectional. To unravel the punishment system is to lay bare the interconnection of people’s struggles against extraction, dispossession, and enclosure organized through racial and gendered hierarchies.

The relationship between abolition (as the goal) and reform (as a means to an end) remains a live debate. Many continue to endorse what Wilson Gilmore calls “non-reformist reforms”—in other words, reforms that shrink the carceral system and thus continue to move us incrementally, in the words of abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba, “toward the horizon of abolition.” Examples of non-reformist reforms include, but are not limited to: abolishing solitary confinement and capital punishment; moratoriums on prison construction or expansion; freeing survivors of physical and sexual violence, the elderly, infirm, juveniles, and all political prisoners; sentencing reform; ending cash bail; abolishing electronic monitoring, broken windows policing, and the criminalization of poverty; and a federal jobs and homes guarantee for the formerly incarcerated.

Both the short-lived Philadelphia conference and the Journey of Reconciliation have been overshadowed and even forgotten. Houser later described the Journey of Reconciliation as “a bit ahead of its time . . . a planned and often audacious attack on Jim Crow before the civil rights movement was full blown.” Rustin argued that “things we did in the ’40s were the same things that ushered in the civil rights revolution.” Ideas do not arrive fully formed, and movements are not linear, but these histories of struggle provide raw material for us to build a world without gendered racial terror and state-sanctioned violence.

A sprawling carceral landscape has bloated budgets and desiccated our imaginings of what is possible. The kneejerk question is often, What would we do without prisons or police? rather than, What could we do with $200 billion for our communities? But, as Wilson Gilmore points out: “abolition is about presence, not absence.” Incarcerated abolitionist Stevie Wilson added that it “is not just about eliminating something (e.g., police and prisons); it is about creating what we need to live, love and thrive.” At this moment, when abolition feels more possible than ever, we should not look elsewhere for “better” models of policing and prisons, but look deeper within our own history for better models of liberation.