This essay appears in print in Left Elsewhere.

When I told the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II that I also had family from small-town eastern North Carolina, he was delighted. “My people are from there,” he chuckled. “We might be cousins!”

This sense of the interconnectedness of rural life in the South, reflected both in personal genealogies and political histories, has served as the backbone of Barber’s call to rebuild the struggle for social justice on a moral foundation. The longtime pastor of Goldsboro’s Greenleaf Christian Church, Barber was president of North Carolina’s NAACP for more than ten years. During this time he helped to launch the Forward Together Moral Movement, which gained national attention for its Moral Mondays protests at the North Carolina General Assembly. Amidst the hard-right, Tea Party–style takeover of state government, this movement used civil disobedience and coalition building to combat a variety of injustices such as voter suppression, environmental devastation, and cuts to social welfare programs.

Last year Barber joined with others in reviving Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign in an effort to address poverty as a moral issue. In October 2018, the MacArthur Foundation recognized his commitment to building progressive movements and “broad-based fusion coalitions” with its prestigious Genius grant.

Grounded in a deep appreciation for movement history, Barber’s goals and methods upend conventional political axioms, and his successes make a compelling case, as he says, that “the solid, red South is very vulnerable”—a prospect we discussed in the following exchange in mid-December.

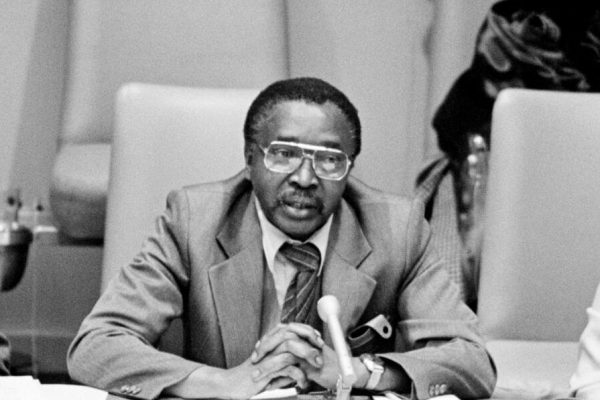

— Toussaint Losier

Toussaint Losier: In your book The Third Reconstruction: How a Moral Movement Is Overcoming the Politics of Division and Fear, published the year Donald Trump was elected, you detail how years of pastoral care and community organizing in rural Virginia and North Carolina led you to discover that “fusion coalitions rooted in moral dissent have power to transform our world from the grassroots community up.” Could you explain what you mean by “fusion coalitions”?

William Barber: When we look at history, we find that almost every progressive achievement—from abolition to social security to civil rights—grew out of some form of fusion politics with a moral underpinning, not a policy underpinning. When white abolitionists and black abolitionists, slaves and former slaves, Quakers and white evangelicals of that day (not the kind we talk about now) fused together, they were able to create an abolition movement.

When King talked about the Poor People’s Campaign, he was talking about fusion. He said it was his campaign, but actually he pooled together twenty-five groups—from Jewish groups to welfare rights workers—in the initial meeting.

So, for me, fusion is when people are brought together, and they fuse their ideas, their intellect, their power, but they do it from a moral critique. They look at society through the lens of our deepest moral issues. In 2008 my organization mapped the way North Carolina politicians voted in the state legislature. We found that the same people voting against environmental justice were also voting against public education. And the same people voting against public education were also voting for voter suppression laws. We realized that these interlocking injustices required an intersectional response. We were able to show that poor black people and poor Latinx communities and poor white communities and poor Native American communities were all being hounded, haunted, and hurt by the same politicians.

And this was when Democrats were in control! I want to emphasize that we didn’t start the Forward Together Movement when the Republicans were in office. For years we had been fighting Democrats to get same-day registration and early voting passed in North Carolina. For years, when we worked in our silos, it didn’t get done. Once we came together with all our partners and tacked our agenda on the door of the legislature like Marin Luther with the Ninety-five Theses, that’s when we were able to get same-day registration and early voting passed.

TL: The Moral Monday protests, where you and others enter the North Carolina legislature peacefully and are then arrested each week, started in 2013. What has it meant to have that kind of ritual? That embodied practice of showing up week in and week out with the faith that you can make a difference, but relying on, as the Apostle Paul said, “the evidence of things not seen”?

WB: Well, down through history, we’ve never won anything with one march, one tweet, one speech—that is a misreading of history. We’ve always won progressive and revolutionary growth in this country through campaigns. Through 381 days of having a Montgomery bus boycott, for example, or through years of the abolition movement. Persistence in a movement is a ritual you must have. You must have a deep commitment to civil disobedience and be willing to put your bodies on the line in a nonviolent way, rooted in love and justice, to dramatize the ugliness of what’s going on.

‘We’ve never won anything with one march, one tweet, one speech. We’ve always won revolutionary growth in this country through campaigns.’

What too often happens in the United States today, particularly with some progressives, is we put too much of our actions into electoral campaigns. And when the campaign is over, and we lose, we go home until the next campaign. Even extremists don’t do that. Even when they’re in the minority, even when they lose a vote, they continue to organize. In some ways they’ve stolen from us what people such as King instructed us to do.

Now, when the Republicans took the majority in 2013, we found that they were extremists on steroids. In the first fifty days, they attempted to undo everything that we had won and pushed for since 2008. They denied Medicaid expansion to 500,000 people in North Carolina—342,000 of whom, by the way, are white. They went against immigrants, the gay community, and women. They denied a minimum wage increase, even though we had won an increase earlier. And then they went after voting itself.

So we decided then that if they were going to crucify the poor, crucify women, crucify children, crucify the sick—every crucifixion needs a witness. And they needed a consistent witness. People told us, “Well, there’s nothing you can do. They have the majority. You just have to wait until the next election.” But we looked at history and saw that people who made change never waited until the next election. For instance: the Voting Rights Act of 1965—there was no election that year. None of the politicians changed in Congress that year; many of them never even intended to support a voting rights act. But King, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, and the others—they changed the political atmosphere, which forced the change in the politics.

We couldn’t wait for the next election. We decided with the Moral Monday Movement that we needed to have a nonviolent civil disobedience campaign every week to drive home for the public what was happening and to ensure that what the politicians did didn’t happen in the dark. We believed that a lot of people didn’t actually know what was going on and holding just one protest or march would not politically educate them. Doing it every Monday gave us a stage to address the issues; it created a following with the media; it created our own social media. It allowed us to shift the narrative, and let people see what was going on.

It also forced the legislature to constantly respond—and they didn’t do well in their responses. After the first six weeks, Governor Pat McCroy, who signed all these regressive bills, went from a 50 percent approval rating to under 40 percent and then never recovered. The legislature dropped to 24 percent approval in the polls and also never recovered.

‘We decided then that if they were going to crucify the poor, crucify women, crucify children, crucify the sick—every crucifixion needs a witness.’

On the flip side, our annual event went from 20,000 people to over 80,000. We were then able to add to our efforts. Lawyers came to offer their services pro bono, and we filed a major lawsuit against voter suppression. Three years later, we won. That would have never happened if we just had one annual event. We constantly said to people that we’re not building a moment, we’re building a movement.

TL: And as the movement grew, you were very deliberate about drawing the distinction between a partisan movement and a moral movement. You tell the story of being invited to speak in Mitchell County, a heavily white county in western North Carolina. Can you reflect on what that invitation meant, and how you were able to resonate with folks who might initially consider themselves on the other side of fence?

WB: When we looked at these interlocking injustices, we looked at them not from the standpoint of Democrat or Republican because those are puny, small terms that keep us in our silos. Everybody uses them, but they’re designed in tribalism and they’re used for tribalism. People are more than that, but we still automatically look at people and pigeonhole them. Most people don’t know this, but at least 50 percent of the people who got arrested in North Carolina during Moral Mondays were white—even though the movement was being led by someone who identifies as African American. (My ancestors were white and black.) But if you’re black and you’re talking about issues, that makes you a civil rights leader, not a moral leader. If you’re pushing for voting rights, you must only care about black people voting—you don’t want to talk about issues that impact all people.

‘At least 50 percent of the people who got arrested in North Carolina during Moral Mondays were white.’

What we found is that by framing our message from a moral perspective, we got people to stop and listen. Then it also opened us up to go to places such as Mitchell County that we would not have been able to go if we were just a blue movement or a left movement. So we would go to Mitchell County, which is 98 percent white and about 80 percent Republican, and say, “Did you know that your politicians are refusing to raise the living wage, and you have so many people here who need it? Do you realize that a thousand people in this county could get health care, but your elected officials are throwing up these dog whistles that would suggest lazy people (i.e., black and brown people) are going to get free stuff when, in fact, the majority of people who would benefit from Medicaid expansion in North Carolina are white?”

By having that kind of conversation, we helped people not be stuck in those puny terms, but see what was going on in a much broader way. That then allowed us to build this fusion coalition.

TL: What led you to resurrect the Poor People’s Campaign nearly fifty years after King’s death? What does King’s vision have to offer us today, especially when it comes to the failure of our political leaders to address the crisis of poverty and the potential gains to be made by addressing it as a moral issue?

WB: Fifty years ago, King talked about poverty, racism, and militarism—the three evils. These days, we have five evils in our democracy. One is the systemic racism that you can see through voter suppression, resegregation of public schools, a new Jim Crow prison system, and the mistreatment of immigrants and Native Americans.

Two is systemic poverty, because we don’t have 40 million people in poverty, like the U.S. Census says. We have 140 million people struggling—almost 43 percent of all the people in this country—and the majority of them are white women, children, and the disabled.

Three is ecological devastation, which is paired with the fact that 39 million people right now don’t have health insurance.

‘King talked about poverty, racism, and militarism—the three evils. These days, we have five evils in our democracy.’

Four, this military war economy. We budget $700 billion every year for defense. The average CEO of a military contractor earns $19 million a year while the average private in the U.S. Army makes less than $30,000—some have to be on food stamps.

And five, we have a religious Christian nationalism—which is a form of heresy—that says the only moral issues allowed in the public square are abortion, gay people, praying in schools, and guns. Some issues are not about left versus right, but right versus wrong.

TL: What lessons have you drawn so far from the Poor People’s Campaign? Where do you see it going?

WB: We’ve learned that we have to shift the narrative because our politics right now is not designed to address poverty and racism. And that is a fault both of Democrats and Republicans, but in different ways. Republicans often want to blame poverty and racism on personal morality, and sometimes Democrats want to engage in the kind of neoliberalism that says if you just focus on the middle class and working class, then you’ve fixed everything.

But almost every state that is a voter suppression state is also a high poverty state, a state that has denied health care, a state that has denied living wages. So, what we’re learning and showing people is how these things are connected and why you can’t just operate in your own siloes. You can’t say, “Well, I care about health care, but I don’t care about voting rights.”

You know, when King called for the Poor People’s Campaign, a lot of people walked away from it. What we’re finding now is that people, including the religious community, are coming to it. There’s a large number of religious bodies ready to join and engage this movement.

‘Democrats want to engage in the kind of neoliberalism that says if you just focus on the middle class and working class, then you’ve fixed everything.’

We’re doing deep work in the South because it holds the key to the transformation of this country. If you take the southern, former slave states, that’s 170 electoral votes right there. Progressives have given those states away, for the most part. But because of shifting demographics and the ability, when it’s time, to bring this coalition together, the South can be changed. They’re not so much red states as they are unorganized and unmotivated states.

A lot of people are just not engaged in politics. Close to 120 million people didn’t vote in the midterms. A lot of them don’t vote because they never hear their issues. We have to force this change of narrative. We are beginning to see this happen, even with the near-victories of Stacey Abrams in Georgia and Andrew Gillum in Florida. But I’m not talking about the individuals; I’m talking about the coalitions that came together in those states. They are showing that the solid, red South is very vulnerable—that it can be broken.

The South is not going to be transformed through electoral politics every two years. It’s going to be transformed through movement building. And if we build that kind of movement—if we shift four or five southern states—we fundamentally shift the politics of the whole nation.