Many on the left had hoped that Republicans would refuse to cooperate with the populism of Donald Trump. Yet Republicans who pontificated about the perils of executive overreach under Obama have so far marched in lockstep behind Trump’s flurry of executive orders. Most now seem happy to defer to a president who prefers rushed executive measures to deliberative legislation.

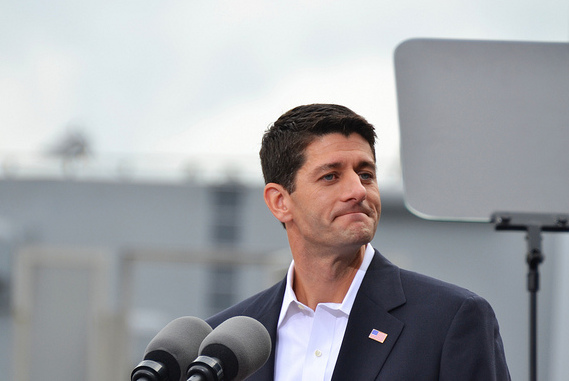

The shift has been perhaps most striking in the case of House Speaker Paul Ryan, a disciple of the conservative Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek. Ryan has regularly acknowledged Hayek’s influence, to the point of distributing Hayek’s canonical Road to Serfdom (1944) to staff members while pursuing the vice-presidency in 2012. The core of Hayek’s classic is a defense of the “rule of law,” defined as the idea that “government in all its actions is bound by rules fixed and announced beforehand.” For Hayek, it is critical that these rules treat everyone the same. General rules, he explains, guarantee impartiality and equality before the law, prerequisites of a free society. When government follows general rules, Hayek claims, it creates opportunities open to all, rather than rigging things to favor certain individuals or groups.

Why then has Ryan responded to Trump’s executive measures and ad hoc dealmaking by vigorously cheering agreements with large companies and praising Trump’s executive order against Muslims and refugees? Perhaps it is hypocrisy and opportunism: strict rule of law and prohibition against individual measures applies to Obama and progressives, it seems, but not Trump. A deeper dive into Hayek’s oeuvre, however, suggests that Ryan’s motivations may be consistent with Hayek’s commitment to the defense of classic liberalism—if necessary even at the cost of sacrificing democracy.

First published in 1944, The Road to Serfdom’s main target was planned economies, for Hayek a category oddly including both Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany. Command-style economies could not possibly maintain fidelity to the rule of law, Hayek thought, and the rule of law’s dismantlement under totalitarianism was the inevitable result of any experiment with government planning. Postwar liberals and progressives tempted to build on successful wartime planning, he warned, threatened to take their countries down the “road to serfdom.”

Read as a polemic against not just Nazism and communism but also the welfare state, Hayek’s jeremiad became a rallying cry for postwar conservatives. By 1994, when Newt Gingrich circulated copies to the new Republican congressional majority, his understanding of The Road to Serfdom was inflected by the interpretation of a generation of conservative thinkers such as Milton Friedman. Friedman’s 1994 preface to The Road to Serfdom situates Hayek as a critic not only of totalitarianism, but of progressive social interventions such as President Johnson’s Great Society, including Medicare and Medicaid, and even George H. W. Bush’s Americans with Disabilities Act or his robust enhancements to the Clean Air Act. Conservative views of the book’s target had shifted, in other words, such that Clinton did not need to be a Hitler or Stalin to pose a serious threat to classic liberalism.

Trump’s authoritarian populism runs counter to Hayek’s prescription in The Road to Serfdom. His wrangling with Carrier Corp., concessions from Boeing over Air Force One’s price tag, threats to penalize automakers for moving production abroad, deals with corporate leaders at White House meetings: none of this meshes with The Road to Serfdom. Trump’s attacks on Nordstrom—and Kellyanne Conway’s astonishing appeal to FOX viewers to “go buy Ivanka’s stuff”—make a mockery of Hayek’s preference not only for limited government but for state action based on general rules. Policymaking via ad hoc deals, with noncompliant firms facing public rebuke, ominously corroborates Hayek’s view that individualized executive decrees are tools “used by the lawgiver upon the people and for his ends.”

As Cass Sunstein recently observed on Bloomberg View, it is also bad economics. Companies now have perverse incentives to curry presidential favor and avoid Trump’s wrath, a scenario unlikely to encourage economic rationality. Appearances to the contrary, Trump’s personalized deals for firms willing to do his bidding have nothing in common with serious efforts to tame globalizing capitalism. One urgent political task for progressives is to make this difference clear to working-class voters susceptible to Trump’s flimflam.

The Road to Serfdom was not Hayek’s only key text, though, and his three-volume Law, Legislation, and Liberty (1973) offers an explanation, beyond cynicism, for why Hayek devotees such as Ryan are willing to aid Trump.

In Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Hayek directly targeted the welfare state. Whereas Road to Serfdom left some room for government social policy, Hayek’s late work diagnoses the emergence of a shadowy “para-government,” overrun by organized groups aiming “to divert as much as possible of the stream of governmental favor to their members.” Hayek held so-called para-government responsible for destroying legislatures. Although on paper still powerful, the legislature has become a “playball of the separate interests it has to satisfy.” Legislatures are so busy providing special favors to organized groups they no longer deliberate properly or promulgate general laws. The welfare state, and especially the left-leaning groups it benefits (labor unions, public employees), destroy legislatures and the rule of law. Those hoping to save them need to figure out how to push back.

How might conservatives do so? By advancing drastic institutional changes even Hayek conceded could seem undemocratic, such as making voting a once-in-a-lifetime act, for example, and lengthening legislative terms to fifteen years. Resting on popular support, the welfare state’s curtailment required attacking democracy.

Although congressional Republicans seem ominously hostile to minority voting rights, they have not gone so far as to pursue Hayek’s proposals in Law, Legislation, and Liberty. Yet Hayek’s logic helps explain why Ryan has made his peace with Trump. Hayek warned his readers not to make a fetish of democracy, and this clarifies why Ryan and other small-government Republicans seem unworried that Trump took the presidency without winning the popular vote.

Despite his populist rhetoric, Trump is eager to employ the presidency’s arsenal of decisional weapons to get Hayek’s job done. His executive orders target “intrusive” banking and financial rules, Obamacare, and other recent regulatory initiatives. Trump’s cabinet and department appointees promise to fight against major economic, environmental, and social regulations. One of the Obama administration’s signature accomplishments, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, will likely be gutted. Trump’s pick for labor secretary, Andy Puzder, has spent much of his career beating up organized labor, just as Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has used her sizable fortune to attack public schools and teachers’ unions. No president in modern time has been as hostile to socially progressive initiatives or regulation as is Trump.

For followers of Hayek eager to smash the “para-government” they deem culpable for political dysfunction, Trump—warts and all—must look like a godsend. Behind closed doors, Ryan and his colleagues may worry about Trump’s disdain for the rule of law. Yet they appreciate his full-court press against the components of the welfare and regulatory state that progressives hold dear. Ryan and other Republicans may have made a deal with the devil. Yet Trump remains very much their devil.