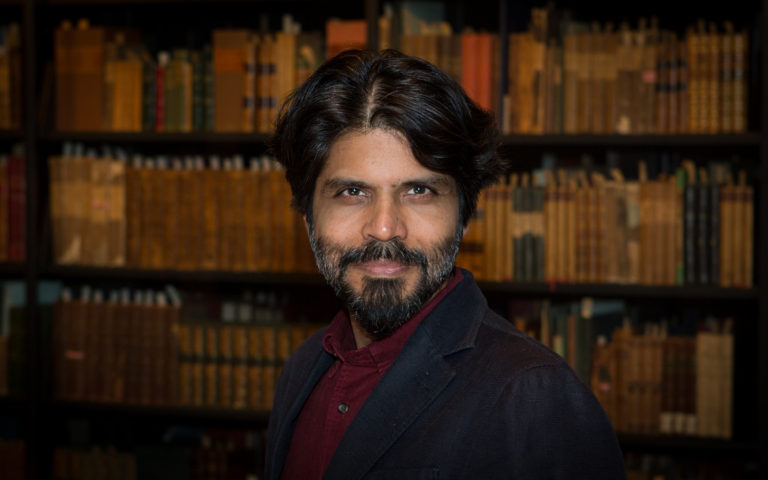

Pankaj Mishra does not suffer fools. Born and raised in North India, the forty-eight-year-old writer was expected to join the civil service after graduating from university; instead he moved to a small village in the Himalayas for five years and wrote literary reviews for the Indian press. In 1995 he published his first book, a travelogue populated by colorful and diverse characters living at the intersection of globalization and Indian tradition. Since then, he has turned out numerous essays, edited an anthology, and published a novel and five books of nonfiction, using his incisive pen to expose the devastating consequences of Western imperialism, globalization, and capitalism.

Five years ago I interviewed Mishra in these pages to discuss his book From the Ruins of Empire (2012), which crafted an epic narrative of Middle Eastern and Asian communities seeking empowerment after centuries of European colonization. Mishra has since turned his focus to the origins of modern reactionary forces—from the Islamic State to Brexit and the presidency of Donald Trump. Longlisted for the Orwell Prize, his latest book, Age of Anger (2017), seeks to explain why millions feel disenchanted by promises of the progress that was supposed to be delivered by liberal democracy. He traces this phenomenon to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when communities in Africa and Asia were crushed under the imperial wheels of Enlightenment. These ideologies of the elite could not operate, he says, without “intellectual racketeers,” the thought leaders who subordinate their intellect and conscience to gain access to power and wealth. Among the current iteration of thought leaders, those now shilling for neoliberalism instead of Enlightenment, he has publicly blasted psychologist and best-selling author Jordan Peterson, whom he accuses of peddling “right-wing pieties seductively mythologized for our current lost generations.”

In this exchange, Mishra and I discuss Trump’s America First isolationism and its consequences for a rising Asia; the rise of right-wing Hindu nationalism under Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi; Europe’s flirtation with authoritarianism and anti-immigrant hysteria; and the role of the public intellectual in the face of imperial injustice.

—Wajahat Ali

Wajahat Ali: Trump campaigned on an “America First” platform, vacating the United States’ role as a global superpower in order to pursue a nationalist, protectionist, and isolationist vision. China has stepped up to fill the void; it is still committed to the Iran Deal and Paris Agreement and has made heavy investments in Africa and Pakistan, not to mention flexing its muscle in the South China Sea and seeking improved relations with North Korea. Is the axis of power pivoting to a rising China? A well-known filmmaker who lives in South Asia once told me, “Yes, America has its many sins, but at least it has a soul. Imagine what will happen if China or Russia replaces it.” And here we are.

Pankaj Mishra: I don’t think Asians or South Asians have much cause for celebration if power is indeed shifting to the East—if there are now plenty of crazy rich Asians as well as Americans. One has to step away from these simple formulas and ask, whose power, whose wealth? Who in Asia will these transformations empower or enrich, and what will be the political consequences of deepening inequality in such populous countries? Asians have shown themselves very capable of the same kind of calamitous blunders as those of their former Western overlords. Japan’s history of militarism and imperialism should be a warning to all those who look to China; to this day the ghost of nationalism is yet to be exorcised there. And we know about South Asia’s inability to defuse its toxic nationalisms or provide a degree of social and economic justice to its billion-plus populations.

Supremacy of all stripes—racial, ethnic, national—works in insidious ways, burrowing deep inside impeccably liberal minds.

I also think we need to question the idea that Trump’s America First agenda is unprecedented, that the U.S. imperium—whether under Republicans or Democrats—has not continuously violated international norms. Didn’t Barack Obama threaten to renegotiate NAFTA? Didn’t George W. Bush put Iran in the “Axis of Evil” and openly scorn France and Germany for failing to join his misadventure in Iraq? It has become too easy since Trump’s ascension to say that the United States once advanced liberal democracy and freedom. This was never the view from India or Pakistan, let alone Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The United States was and is a self-interested global hegemon; it has supported the world’s worst despots when they seemed to protect U.S. interests. The only difference is that Trump openly repudiates emollient rhetoric and does not hesitate to alienate U.S. allies.

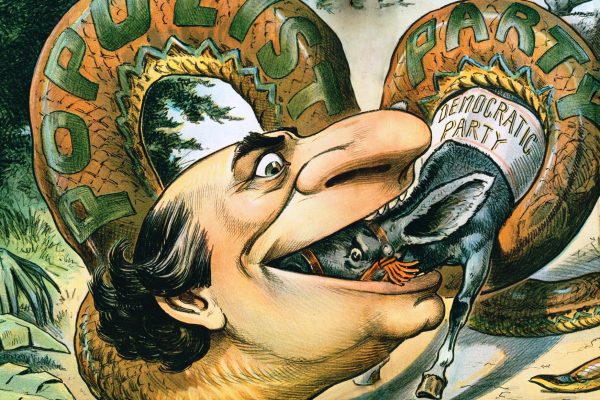

WA: And he is not alone. A string of right-wing leaders—Benjamin Netanyahu, Rodrigo Duterte, Viktor Orbán, Narendra Modi, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—are still winning democratic elections and retaining popularity despite resorting to authoritarian tactics. In your most recent book, Age of Anger (2017), you argue that this troubling trend is the inevitable afterbirth of modern progress. Contrary to Francis Fukuyama’s prediction, Western liberal democracies did not herald the “end of history.” Instead they seem to have contained within them the seeds of our destruction. Is there any hope for these systems and institutions? Or, in their place, is absolutism—whether from the right or the left—the inevitable result?

Liberal democracy—with its subordination of such substantive matters as equality, freedom, and general welfare to procedural issues, elections, and norms—has turned out to be the best way of concentrating oligarchic power.

PM: As a writer I am more interested in describing the past accurately than in outlining the future; we need a new past if we are to make sense of our intolerable present or work to change it. One of my favorite historians, Carl Becker, wrote that “in periods of stress, when the times are thought to be out of joint, those who are dissatisfied with the present are likely to be dissatisfied with the past also.” In that vein, I have been trying to advance a story of the past that helps us understand the deep roots of our global crisis, the present outbreaks of demagoguery—in the heart of the modern West as well as in Asia and Africa, where it had been too easy to blame religion and culture for the failings of postcolonial societies. In the book, I am pushing back against the dominant narrative that presents grotesquely unjust societies, built on violence and dispossession, as the best possible world.

Boosting Western-style democracy and capitalism, and ignoring their long history of complicity with imperialism, the end-of-history narrative has made it too easy to deny the simple fact, as Orwell put it, that “the European peoples, and especially the British, have long owed their high standard of life to direct or indirect exploitation of the coloured peoples.” Those of us who grew up in places despoiled by capitalist imperialism—India, Nigeria, China—were left in no doubt by our history textbooks that it brought our world into being and made it what it is. These nationalist histories had their own distortions, but they got some basic things right. Look at the Chinese narrative about the “hundred years of humiliation” or the Declaration of the Independence of India (1929) and you see the same historical outline: how the forces of industrialized production in nineteenth-century Europe and the United States expanded through genocide and slavery, or, at the very minimum, through military invasion, occupation, and dispossession.

It has become too easy since Trump’s ascension to say that the United States once advanced liberal democracy and freedom.

The strange thing for me, when I first left India in my mid-twenties and traveled to the West, is how differently people saw this history. Structural and extensive violence had been carefully hidden from its long-term beneficiaries. They saw themselves as the inheritors of wonderfully inventive white people who had mapped the world and created the political and economic possibility of individual freedom for everyone. In truth, these were the paternalistic forms of a harsh theory and practice of domination and supremacy, which presumed to bring civilization to benighted natives.

Supremacy of all stripes—racial, ethnic, national—works in insidious ways, burrowing deep inside impeccably liberal minds. In retrospect it seems a bit unfair of me to single out a figure such as Niall Ferguson for peddling bogus histories of empire, free trade, and democracy: those ideas have long informed much mainstream and respectable journalism. So effective have those narratives been that even the long-term victims of the history of violence have found it hard to build international solidarities. In the latter half of the twentieth century, most Asian, African, and African American thinkers and activists recognized that decolonization and the civil rights movement were part of the same battle—but that essential view has been mostly lost. Writers from historically disadvantaged communities have become more parochial and less internationalist in their thinking. In a recent review I pointed out how even such a sensitive and brilliant writer as Ta-Nehisi Coates could not relate the African American experience to the history of Asia and Africa—and how this failure made him invest too much faith in Barack Obama, a dutiful sentinel of the U.S. imperium.

We are beginning to understand what anti-imperialists such as Du Bois and Gandhi saw so clearly: white supremacy is the malign force of modern history.

Of course, self-congratulatory white histories—Plato to NATO via the Reformation, Renaissance, and Enlightenment—are not very persuasive today, and long-suppressed realities have erupted to the surface. We are beginning to understand what anti-imperialists such as Du Bois and Gandhi saw so clearly: white supremacy is the malign force of modern history. With old-style racist imperialism no longer an option, those fearful of the loss of white power look to brute authority figures. These ugly facts tell us that a system so parasitic on violence and dispossession, so prone to generating cruel inequality and inflicting injustice, should not be saved. We need a fresh vision of political and economic possibilities—one that is not derived from the history of capitalist expansion and imperialism.

WA: At the same time that identities are consolidating once again around religion, ethnicity, and nationality, we are also seeing an erasure and reconfiguration of bodies, borders, and boundaries. The sins and ghosts of many Western nations are ending up at the doorstep of Europe, testing the limits of its alleged liberalism. Will Europe be able to reconcile its history of racism, colonialism, and Islamophobia with its refugee crisis?

PM: We have to examine more closely just when and how Europe became an exemplar of liberal democracy—an idea that derives from Europe’s wholly exceptional postwar period, when it recovered from a long stint in pure hell. We have all heard of the genocide committed by Germans. But ethnic cleansing was at the foundation of many of Europe’s contemporary nation-states. Even during les Trente Glorieuses (the thirty “glorious” years between 1945 and 1975), Europe was hardly a global exemplar of liberalism. Spain and Portugal were closer to despotism than democracy until the 1970s; parts of rural Italy, Spain, and Portugal actually looked like the Third World.

We need a fresh vision of political and economic possibilities—one that is not derived from the history of capitalist expansion and imperialism.

It is true that by the 1990s the rights of women, factory workers, and sexual minorities were never as secure as in the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia. But Europe never ceased to have problems with accepting people from Asia and Africa, who were brought in to service the new miracle economies. The coming of neoliberalism after the fall of communism only made things worse, spreading a new ideological fervor on behalf of efficiency, flexibility, and marketization. Its devastating effects in Russia in the 1990s already pointed to a new era of oligarchy and messianic politics. Nearly thirty years later, its consequences in Europe—widespread dispossession, destruction of traditional livelihoods, denial of dignity, and compensatory scapegoating of immigrants—are all too clear. Whiteness has reemerged as a virulent political religion, but it is important to remember that large parts of Europe were never really comfortable with racial heterogeneity.

WA: You’ve been critical of India’s engagement with globalization. Modi was elected prime minister in 2014, having run on Hindu nationalism and his pro-business record. Since then India’s economy has grown, but there has also been rampant income inequality and a surge in mob violence against minorities, especially Muslims accused of eating beef. In July India’s Supreme Court condemned this “mobocracy.” How have Modi’s economic and political policies, which were supposed to create more open and free societies, been used and manipulated for oppression?

The answer to the many problems, inadequacies, and dangers of democracy should never be less democracy.

PM: We have to look at what specific processes of globalization amount to in India, rather than accept at face value the ideological claims made for them. There has been a lot of self-congratulation—among both Indian and Western commentators—about Indian democracy, but none of it can explain a figure such as Modi and why India is more violent today than it was under British rule. To examine these particular experiences is also to begin to learn what kind of politics and economy work best for our complex societies. It is to move away from neo-imperialist visions of Asia, according to which its countries are forever competing in a race to Western-style modernity. Along with U.S. libertarian fantasists, many liberals in India welcomed Modi, seeing him as an economic modernizer and taking for granted the resilience of democracy. For many he was proof of India’s democratic revolution. His record of instigating violence against minorities was either ignored or denied. Anyone aware of his background—for example, his lifelong membership in Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, an organization inspired by European fascists—knew what he would do in power: try to forge a Hindu nation by demonizing minorities and left-leaning dissenters. I keep saying this: it is our own ignorance, or denial, of the tragically entwined history of capitalist expansion and democracy that makes us expect benign outcomes from them.

WA: Speaking of Indian democracy, you have written that “the formal and proceduralist features of democracy—elections—have superseded their substantive aspect: strong, accountable, and fair-minded institutions and officials.” How can Indians engage the democratic process in a meaningful manner? If this is not possible, then is democracy the best solution for achieving political equality in India?

PM: The answer to the many problems, inadequacies, and dangers of democracy should never be less democracy. It is true that in many parts of the world, ordinary citizens feel disenfranchised by alliances between national politicians and global businessmen. Liberal democracy—with its subordination of such substantive matters as equality, freedom, and general welfare to procedural issues, its obsession with the holding of elections and the preservation of norms—has turned out to be the best way of concentrating and deepening oligarchic power. This is the main reason it has provoked such furiously emphatic rejections worldwide from voters who feel utterly deceived and powerless, who no longer believe that liberal democracy is superior to authoritarian rule.

We say we believe in democracy. But the urgent question, wherever we are, is what kind of democracy?

Still, the answer is not less democracy, or authoritarian populism. We need more democracy in India and elsewhere—substantive democracy. It is a truism that democracy in its Western habitat struggled for a long time to concede equal rights to slaves, women, workers, and the colonized on the grounds that they were deficient in reason. The project of equality and freedom was also continuously undermined by the rise of a market economy and a bureaucratic state, which placed economic and political rationality above moral claims. In many ways democracy in its ideal form has been more clearly formulated in postcolonial nations, where it was attached from the very beginning to promises of equality, social and economic justice, and the welfare of the poor and underprivileged castes. We need to rebuild and reinstitutionalize this vision. We say we believe in democracy. But the urgent question, wherever we are, is what kind of democracy? One where wage slavery is the norm? Where politicians deploy the ample tools of demagoguery to get elected and then ignore ordinary voters? Or, instead, one in which power is not concentrated at the top and people feel themselves to be citizens as well as voters, able to participate in making decisions that affect their lives? The latter is obviously preferable, but it will be difficult to work our way to it. Political elites have used elections and parliaments as instruments of legitimacy; they exercise monopoly power in the media as well, and they will not give it up easily.

WA: Your critiques of Salman Rushdie and Niall Ferguson have generated considerable notoriety. And you recently wrote a scathing review of Jordan Peterson’s best-selling 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, calling it a brand of “intellectual populism” that is “packaged for people brought up on Buzzfeed listicles,” a category that seems predominantly to include young men. You also accused him of romancing the noble savage. He responded by calling you an “arrogant, racist son of a bitch” and threatened to slap you—a threat he reiterated at a conference I recently attended. As a person of color, a South Asian man in particular, do you feel you have a particular role as a public intellectual in challenging academics who find comfort in an order and hierarchy that privileges white men? What should be the role of public intellectuals—especially those of color—today?

Our political crisis today is, first and foremost, a global intellectual crisis—the result of a feckless homogenization of thought.

PM: I think the fact that we have to ask this question shows how serious the problem has become. Many people we think of as intellectuals—our “thought leaders”—are basically global professionals, adept movers in the networks of Oxbridge, the Ivy League, the London School of Economics, think tanks, Davos, and Aspen. The result, as we see more clearly after Trump, has been a stultifying sameness in the public intellectual sphere: loud echo chambers in which you have a whole class of writers and journalists saying the same things over and over again. This is why our political crisis today is, first and foremost, a global intellectual crisis—the result of a feckless homogenization of thought.

We have had these academic superstars who went on about knowledge and power but were themselves busy climbing social ladders. Even writers and intellectuals with a great deal of integrity and courage have become too professionalized, too career-oriented, and too concerned not to upset their peers—not to mention those they regard as their more famous and successful superiors. This professional docility has allowed figures such as Ferguson to flourish, and that is why criticism drives them to hysteria today.

There is hope, though. It is true that Trump has opened up space for all kinds of intellectual racketeers, who pose as members of an intellectual Maquis while trying to save or advance their professional careers. These dead-end centrists—most of whom moonlighted as laptop bombers during the Iraq War and often advised the Clintons, Blair, Bush, and Obama—still dominate many high-circulation periodicals. They present a huge but neglected problem. You can get rid of incompetent or venal rulers through the democratic process, but there is nothing you can do with the deadweight at the highest editorial levels of mainstream media. These figures who were wrong or clueless about every major domestic and foreign policy issue—from Russia in the 1990s to Iraq and the financial crisis—remain entrenched, starving the public of much-needed fresh ideas and compounding the political calamity of elite centrism with a massive intellectual and moral failure.

You can get rid of incompetent or venal rulers through the democratic process, but there is nothing you can do with the deadweight at the highest editorial levels of mainstream media.

But in response, the intellectual culture of the left is flourishing once again after many barren decades—often outside its usual setting of academia, in small magazines and webzines, including these very pages. Many academics—a few names attest to their range: Amia Srinivasan, Adam Tooze, Kate Manne, Samuel Moyn, Aziz Rana, Nancy Maclean, Quinn Slobodian, Jennifer Pitts, Corey Robin—have stepped into the fray with complex yet accessible analyses of the impasse we inhabit today. Bold charlatans such as Jordan Peterson will no doubt induce awe at the Atlantic, and Enlightenment-mongers such as Steven Pinker will continue to impress many rich dullards, but they will also be taken to the cleaners by historians and anthropologists.

WA: The Economist has labeled you the “heir to Edward Said.” How do you respond to the comparison?

PM: Not very well. These kinds of intellectual genealogies are very superficial—sound bites, essentially. The important work of Edward Said—the examination and overcoming of degraded and degrading representations of the non-West—is being carried on by many writers, and it is far from finished. It has suffered serious setbacks in the post–9/11 era, which has seen an exponential rise in bigoted ideas, so we need many more people with his intellectual capacity and moral courage to challenge mainstream prejudices. It is also true that Said represented only one side of the great work undertaken by writers and scholars from the non-Western world; there are many Western and non-Western intellectual traditions and figures I feel much closer to.

Writers must insist on the great variety and complexity of the experience that their white audience wants them to simplistically embody.

And one has to ask why the Anglo-American press feels compelled to make such comparisons. It has been indifferent to, if not contemptuous of, the experiences and perspectives of non-white peoples and invests too much in token gestures to diversity, anointing this or that writer—Rushdie yesterday, Coates and Chimamanda Adichie today, someone else tomorrow—as the representative of a nation, race, and religion. Individual writers must reject such a dubious honor—the burden of singularity—and insist on the great variety and complexity of the experience that their white audience wants them to simplistically embody.