Democracy Without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society

Victor Pickard

Oxford University Press, $27.95 (paper)

Victor Pickard’s latest book about journalism and democracy concludes that dark political moments are precisely when we should be envisioning a different future. Of course, the moment he was referring to—before the book went on sale in December—looks downright sunny compared to what’s happened since.

Recent changes at the Atlantic are a striking example of the cruel logic of pandemic-era journalism. In the early days of the pandemic, the publication’s editor-in-chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, wrote to staff: “We have never, in the 163-year history of this magazine, had an audience like we had in March.” By May the magazine had added 90,000 subscribers, yet management still laid off almost a fifth of its work force, citing a decline in revenue from advertising and in-person events. And the issue is not just that journalists are losing their jobs. The jump in the Atlantic’s readership and subscriptions could not prevent dramatic financial hardship, suggesting the business of journalism itself is seriously broken.

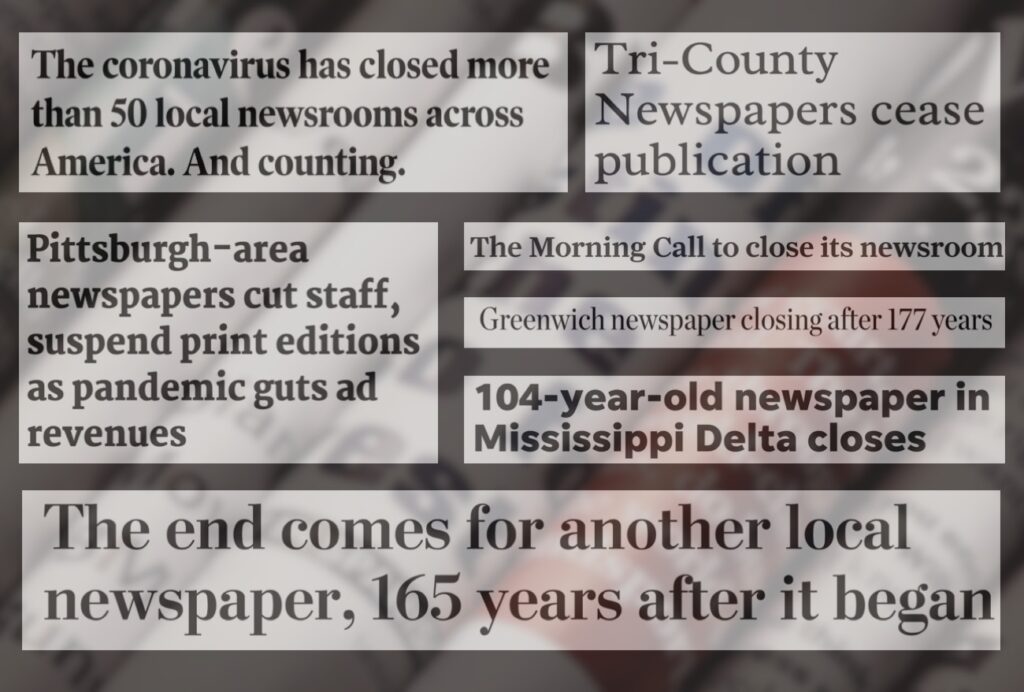

The latest evidence that journalism is seriously broken comes from the way the market has laid waste to news organizations from coast to coast over the last five months.

The latest evidence comes from the way the market has laid waste to news organizations from coast to coast over the last five months, but the trend is not new. The “ghost newspaper,” which looks like a newspaper but contains effectively no local public service journalism, was already on the rise across the country before coronavirus. Consider the Pottstown Mercury in rural Pennsylvania. Reporter Evan Brandt worked hard last year to get some attention to its plight after it was acquired by a hedge fund. When he started at the paper in 1997 he covered a single school district and the municipalities it served. In 2019, he gave his local NPR affiliate the updated numbers: “If you don’t count school districts, it’s 41. If you do count school districts, it’s 50.”

The result is that we have fewer journalists covering more things. And while all of this points to a crisis in the journalism industry, is it also really a crisis for democracy and an informed citizenry? In the 1990s and early 2000s observers hoped that the Internet would enrich journalism rather than ruin it, and that the lowered barriers to entry would mean that we could all be heard—in a good way, not in the manner of today’s misinformation crisis. That rosy democratic vision hasn’t borne out. And as the news industry has suffered, a lot of research has pointed to the fact that without access to local news, people are less likely to vote or to engage with their communities. It is this kind of journalism Pickard is especially concerned about: what he calls “informative, fact-based, policy-related news.” And he’s especially worried that misinformation has all too quickly stepped in to fill the vacuum.

In the COVID-19 era, advertising-supported news organizations—which, in this country, make up most of them—are especially in trouble. With the economy in a nosedive and an uncertain future, many advertisers have canceled contracts. What happened at the Mercury has been repeated, over and over, across the country. Indeed, one study found that at least thirty newspapers closed or merged in April and May, with dozens ending or pausing their print editions. In April the New York Times estimated that 36,000 employees at news organizations around the country had been laid off, furloughed, or had their pay reduced since the pandemic began. Simply put, we’ve left journalism at the mercy of the marketplace, which dictates how much news we get. Of course, if we agree that journalism is essential to democracy—and we should, despite the provocative question in the title of Pickard’s book—then this situation simply doesn’t make sense. The market and democracy have different goals, and when they’re at odds, the latter always loses out.

This argument is important, even if it has not yet gained enough traction to facilitate structural change. That is not for lack of trying; the argument has been made many times, including by Pickard himself in his previous book, America’s Battle for Media Democracy (2014). The new book extends the argument in two ways.

The market and democracy have different goals, and when they’re at odds, the latter always loses out.

First, Pickard contends that commercial journalism inherently leads to misinformation and disinformation. Facebook and other social media platforms benefit when users engage with what shows up in their feeds. As a result, they have a powerful incentive to prioritize what makes us angry or emotional, regardless of the quality of the argument or even its veracity. “Perhaps the real question,” Pickard suggests in the face of this perverse set of incentives, “is why we ever expected anything different to emerge from such a commercialized, profit-driven system.” His second major contribution here is to move from diagnosis to prescription. After conducting an autopsy on the spectacular failure of commercialized journalism, he concludes that nothing short of a publicly funded media can provide us with the journalism we need.

Pickard’s argumentative style will be familiar to readers of his earlier works. He briskly presents copious historical detail, using it to counter commonly accepted narratives about the media to illustrate that things haven’t always been as they are now—and thus that another way really is possible.

One of Pickard’s favorite myths to pick apart is the notion that the U.S. government has no place in funding journalism, a conceit he refers to as a “common historical fallacy.” While this understanding has become libertarian orthodoxy, it wasn’t, Pickard tells us, the intention of the Founding Fathers. Contrary to a great deal of contemporary discourse that interprets the First Amendment as protecting us from government intervention, Pickard, among others, argues that the drafters of the Bill of Rights instead intended the First Amendment to represent a responsibility on the part of the government to ensure the existence of—and access to—the information we need for our democracy to function. This played out, he argues, through serious government investment in communication throughout the nineteenth century, including the rapid development of the postal system.

For Pickard, the upshot of this exercise in demystification is that journalism wasn’t meant to be left to the whims of the market. Policymakers always had the power to create social structures that would support journalism precisely for the essential role it plays in our democracy. Instead, through the choices they made—and those they didn’t, in particular the decision to not build a government-funded public broadcasting system—they opted for the rickety supports of market capitalism. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, advertiser investment in journalism grew steadily, so the problem was not so apparent. But ad revenue peaked in 2005 and now has fallen back to 1980s levels, making the issue painfully obvious. And yet we have remained stubbornly unable to move beyond the libertarian discourse about the freedom of the press. We’re stuck, Pickard argues, in a state of “discursive capture,” in which criticisms of a market-driven media system are hard to come by—at least in mainstream discourse. (Pickard notes that when liberal policymakers and thinkers do occasionally arrive at a critique of commercial media, they become uneasy about their own social democratic conclusions and “retreat to extolling the comfortable sanctities of the market and its propensity for innovation and efficiency.”) In other words, the mainstream conversation is constrained by market fundamentalism, preventing us from confronting the issue systematically.

Policymakers always had the power to create social structures that would support journalism precisely for the essential role it plays in our democracy. Instead they opted for market capitalism.

While Pickard doesn’t give a close analysis of ongoing debates, one of the most high-profile recent arguments about the future of news has pitted those who think nonprofits can save journalism against those who think news organizations should aim for self-sufficiency in the market and that anything else would represent an objectionable form of charity. The latter group is the more powerful: outside of academia, even so seemingly innocuous a proposal as calling for more nonprofits is seen as radical. Government support doesn’t get much play in this discussion—at least not in this country.

Another favorite argument Pickard takes on suggests that the problem would be solved if only newsrooms had adapted faster or were more open to innovations that would monetize their content. This idea, Pickard contends, misses the fact that the crisis is systemic: a new business model isn’t out there waiting to be discovered, because it’s all of capitalism that’s the problem. Those who take this technocratic line—as if all news organizations need is a visit from McKinsey consultants—see journalism as just another product and portray its collapse as beyond our control. The effect is to ignore the market fundamentalism that caused the problem in the first place. Pickard contends instead that the problem with the business model for news in this country is that we haven’t fully embraced the fact that news is a public good, and thus, like other public goods—schools, for instance—cannot be adequately provided by the market.

After challenging these narratives, Pickard lays out his own solution: a robust, public fund to support a public media system. This could take the form of collectively owned news organizations that work with communities to figure out what to report on. As he envisions it, the system would be run by a consortium of policy experts, scholars, journalists and others who engage local communities to build a media system that is “democracy-driven, not market-driven.” Pickard points out that the United States is exceptional in its lack of government support for journalism, with even public media in this country receiving very little government money, on the order of $3 per capita per year. (While this spending varies significantly by country, Norway spent the most in 2014, at $180 per capita.) Again he argues that it didn’t have to be this way. The 1967 Public Broadcasting Act, which created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), noted that journalism was in the public interest. But then, instead of funding it through a tax on television sets—as had been recommended and as is done successfully in other countries—control over its funding was given to Congress, leaving it open to constant, politicized battles. Most recently, that has taken the form of an annual proposal by the president to remove all funding from the CPB. The measure didn’t make it into this year’s budget, but, as some observers have noted, the very attempt helps to erode public support for public goods.

While Pickard suggests that a truly publicly funded model is best, he also proposes a mixed model, presumably in response to widespread antipathy toward government involvement. In this scenario, journalism would be supported through a public media trust fund containing government money—perhaps coming from taxes on electronics and proceeds from the sale of unused public radio and television licenses—but also donations from foundations and a “public media tax” paid by Google and Facebook. (License sales, in fact, are the source of a recently created, $2 million fund for local news in New Jersey, which offers some hope for the future that Pickard envisions.) And he adds that the community must have a role in decision-making for the proposed structure to be truly public—a notion that comes up on occasion throughout the book but is on balance under-examined.

Pickard’s historical research is deep and broad, his counter-narratives are important, and his push for a public option compelling—the most logical answer to the question of where public service journalism should come from in this country. The solution will involve convincing fellow Americans that our media system is an outcome of collective decisions made over many decades, meaning that we can change course. This book is a serious and convincing attempt to make that happen.

Pickard contends instead that the problem is that we haven’t fully embraced the fact that news is a public good, and thus, like other public goods cannot be adequately provided by the market.

Yet it is Pickard’s own detailed and precise presentation of the problem that might temper our optimism. He notes that this historical moment could be the very thing we need to create a new public media system—“absent ideological constraints.” That is a big omission. He points out that polls show significant support for public media, with, for instance, Americans from across the political spectrum rating PBS their most trusted news source for seventeen years running. (Indeed, that survey found that respondents trusted PBS more than any other American institution, including the courts and the federal government.) Still, this support is for an existing institution, and not for the idea of a truly public, government-funded media. That’s why abstracting away ideological constraints feels like ignoring the core of the problem. Despite public opinion, public media remains a favorite punching bag for Republicans, and these days all Democrats can achieve is slight increases to Congressional appropriations for the CPB—nothing close to building out the truly public media Pickard advocates. Indeed, while there is some nuance to the measure (for instance, most Americans continue to trust many federal agencies), Pew Research Center reports that public trust in government is near all-time lows.

Pickard looks back approvingly to early twentieth century opposition to a commercialized press: a loose coalition of radical newspapers, muckraking journalists, and intellectuals such as John Dewey and Walter Lippmann. But that was a time when the hypercommercialization of everything was not a foregone conclusion. These days, school districts are putting advertisements on report cards and public transit authorities are selling naming rights to stations, and, outside of a few small circles, these moves find little pushback. This combination of growing government distrust and acceptance of hypercommercialism suggests an uphill battle for Pickard’s solution.

Part of Pickard’s argument rests on the fact that government has been heavily involved in media in this country, and so it makes sense to expect it to keep doing that. Still, it is important to note that this involvement has often been limited to creating and regulating infrastructure, such as postal roads and airwaves.

It is also hard in these days of reckoning to ignore the racialized nature of our communication system. It’s increasingly clear that the twentieth century liberal consensus was a consensus for middle-class white people. Even in that world, arguments for a government-supported media failed. Pickard acknowledges that one of journalism’s challenges is that it’s not representative of its community. Some journalists, and some communities, have been saying this for decades. The fact it hasn’t changed all that much, at least not within mainstream journalism, suggests that he understates the depth of the challenge before us.

For all these reasons, it is hard to imagine that significant change is coming soon. But the picture is not unremittingly bleak. New Jersey’s experiment with public funding is already putting some of Pickard’s prescriptions into practice, though it’s too early to tell how it will play out. Pickard also suggests that our (nominally) public media stations can help save local news—and this future, too, is already in some ways here. The NPR affiliate in Philadelphia recently absorbed Billy Penn, a millennial-focused news startup that generated significant attention when it was founded, but ended up being unsustainable. And the same has been happening across the country, with for instance the Gothamist joining WNYC, and a PBS station acquiring news nonprofit NJ Spotlight. This type of acquisition might just represent a civic-minded response to the shopping sprees we’ve seen on the corporate level, moves that have left, for instance, Gannett owning a thousand newspapers across the country.

For the chains, acquisition makes sense because economies of scale let them cut resources and make more money. But what if news organizations were being acquired by a benevolent owner instead, like a public media station? Then perhaps economies of scale could be mobilized not to cut but to produce better journalism. In light of Pickard’s argument, this situation might suggest that we’re closer than we think to a de-commercialization of at least some parts of the news ecosystem.

In essence, the challenges that Pickard enumerates are not new. They grow out of what some see as the last big crisis in journalism: the technological realignment of our expectations around information occasioned by the rise of the Internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s. And of course Pickard isn’t the only one writing about the economic collapse in journalism and what should or could be done. Of the large collection of books out recently on this subject, Pickard’s offers perhaps the most radical prescription, even while it fits squarely into the arguments being made by scholars and journalists alike: quality public service journalism is not a given, but it is essential for democracy to function well. To keep it, we need to stage an intervention, instead of just assuming something new is going to arise to fill the gap.