The entrance to the Airtrain at the Howard Beach/JFK A train station was packed with protesters and cops Saturday evening. It was the first day of Trump’s anti-Muslim immigration ban and I was flying to Vermont. As reports of chaos, despair, and terror—as opposed to terrorism—emanated from airports, the president pronounced that his ukase was being executed “nicely.” The word contained the enormity of his ignorance and heartlessness.

The protesters were trying to get to JFK’s Terminal 4, where eleven travelers were being detained. But the police had orders to let only people with boarding passes through the Airtrain turnstile. I handed a cop proof of my legitimacy to cross a barrier that, until that morning, admitted millions of people with no more documentation than a Metrocard with five bucks on it.

“Let them in! Let them in!” the crowd shouted.

“You’re good to go, Judith,” the cop told me.

A woman hollered at a row of officers: “It’s not your job to enforce the illegal, racist policies of a fascist dictator!”

A woman hollered at a row of officers: “It’s not your job to enforce the illegal, racist policies of a fascist dictator!”

I felt a little sorry for the cops, who stood impassively. I thought I’d detected a note of apology in the voice of the guy who took my papers. Unfortunately, it is their job, I thought.

Or is it?

Who will stop the man methodically pulverizing America’s democratic institutions? Congressional Republicans are disinclined. The Democrats don’t look much better, although in response to roars from the base and Trump’s firing of Acting Attorney General Sally Q. Yates—who refused to defend the executive order—a few have pledged to approve no more of Trump’s nominees. Meanwhile, the White House is slicing up any blocs of power within the government—kicking the Joint Chiefs out of the National Security Council meetings, canning the top echelon of the State Department—that might stand in its way. Citizens are mounting a magnificent resistance. But short of storming the capital, how do we halt Trump’s takeover?

Within hours of the president’s issuance of gag orders against the health, scientific, and environmental agencies, an answer came in the form of a tweet from a government scientist at South Dakota’s Badlands National Park: “The pre-industrial concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was 280 parts per million (ppm). As of December 2016, 404.93 ppm.” Suddenly an atmospheric measurement became a political broadside. Soon Twitter accounts with handles such as @ungaggedEPA and @rogueNASA were leaking reality into the alternative-fact universe. By Wednesday afternoon, the list of such accounts had grown to at least fourteen.

Imagine if civil servants refused to cooperate? Call it the Bartleby Strategy.

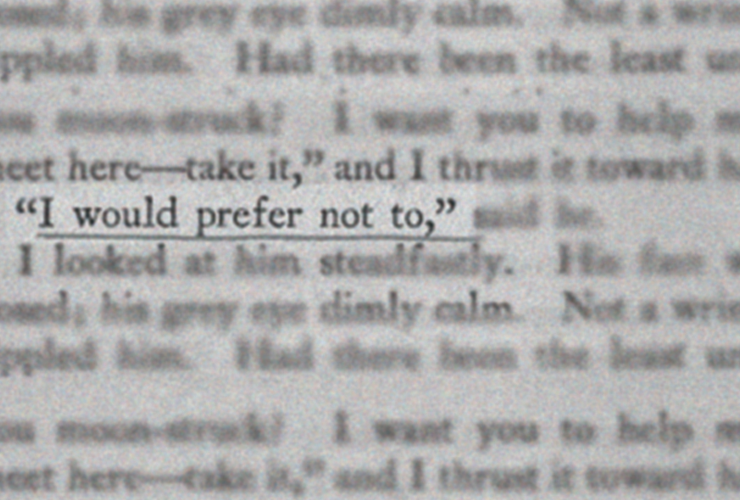

No respect for pencil pushers? Get over it. America’s army of bureaucrats, who number over 750,000 in federal agencies alone, may now be the bulwark between totalitarian plutocracy and constitutional democracy. Imagine if civil servants, from secretaries to social workers to scientists—to police—refused to cooperate? Call it the Bartleby Strategy. Its rallying cry: “I would prefer not to.”

You may dredge up the story from your memory of high school English or read it online. Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” concerns a scrivener—a clerk or copyist—in a Wall Street law office who, after a brief period of industrious work, refuses to perform his job.

“Why do you refuse?” demands his employer, the narrator.

Bartleby replies, “I would prefer not to.”

The lawyer never discovers why. Indeed, Bartleby prefers not to divulge anything about himself or his motives. Mostly he utters one sentence: “I would prefer not to.” The reader is left with the testimony of the narrator, a dealer in “rich men’s bonds and mortgages and title-deeds” who, at the time of the events, holds the title of Master in Chancery in the New York State judiciary. It is a government post, not very arduous “but very pleasantly remunerative.” Is Bartleby protesting the corruption of his boss’s practice? We do not know.

Soon Bartleby is preferring not to do anything his employer asks, including leaving the office. When the lawyer arrives there on a weekend, he finds the door locked and his key, ordinarily under the mat, missing.

Quite surprised, I called out; when to my consternation a key was turned from within; and thrusting his lean visage at me, and holding the door ajar, the apparition of Bartleby appeared, in his shirt sleeves, and otherwise in a strangely tattered dishabille, saying quietly that he was sorry, but he was deeply engaged just then, and—preferred not admitting me at present.

Flummoxed by Bartleby’s presence, and his calm sternness, the lawyer obeys.

I slunk away from my own door, and did as desired. But not without sundry twinges of impotent rebellion against the mild effrontery of this unaccountable scrivener. Indeed, it was his wonderful mildness chiefly, which not only disarmed me, but unmanned me, as it were.

Unable to evict Bartleby, the lawyer fires him. Still he will not leave. The lawyer moves to another office. Bartleby continues to haunt the building. The landlord demands that the lawyer remove him. The lawyer cannot, and has Bartleby arrested. At the jail, the prisoner refuses to eat, and perishes. Having passed from indulgence to hope, irritation to rage to resignation, and finally undone by Bartleby’s passive resistance, the lawyer effectively kills him.

“Bartleby the Scrivener” was published in the furious heat of the nation’s battle over slavery, three years after the odious Fugitive Slave Act.

“Bartleby” has inspired reams of interpretation. Is Melville’s story a case study of depression? A treatise on free will and determinism or personal isolation in an increasingly impersonalized economy? Is it—most pertinent now—a portrait of conscientious objection and the moral and emotional dilemmas of responding to it?

Quite likely the last. The story was published in Putnam’s Magazine in 1853, in the furious heat of the nation’s battle over slavery. It was three years after the odious Fugitive Slave Act; the intervening years had seen the release of Sojourner Truth’s dictated memoir, with a preface by William Lloyd Garrison, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The novella Billy Budd, left unfinished at Melville’s death in 1891, is better known as his book of ethics. In it, the ship’s captain Edward Vere struggles between official duty and personal conscience when he is compelled to court-martial—and thereby sentence to hanging—the legally guilty but morally innocent sailor Budd. “Melville’s narrator here famously recognizes the plural nature of conscience, its relationship to intelligence, its place alongside religion, and the universal access to it humans are meant to enjoy,” wrote Alvan A. Ikoku in the AMA Journal of Ethics in 2013.

But that insight is also fleeting, and there remains a sense that Melville’s work on the matter was unfinished, that in its unresolved qualities his novella describes the unfinished project of post-Civil War society, that it prefigures an ongoing effort to ascertain the conditions under which one may exercise private morality in the setting of contested law.

Ikoku might have been talking about Attorney General Yates’s statement on Trump’s refugee and immigration ban:

My responsibility is to ensure that the position of the Department of Justice is not only legally defensible, but is informed by our best view of what the law is after consideration of all the facts. In addition, I am responsible for ensuring that the positions we take in court remain consistent with this institution’s solemn obligation to always seek justice and stand for what is right. At present, I am not convinced that the defense of the Executive Order is consistent with these responsibilities nor am I convinced that the Executive Order is lawful.

The American moral project that engages Vere and Yates, and maybe Bartleby, is still unfinished. But the captain and the attorney general are different from the clerk. Their decisions are not without personal consequence, but the two are vested with the authority to make them.

It is no small thing for government workers to stage a Bartlebean rebellion. But our democracy may depend on it.

A civil servant does not have this prerogative. Firing one is intentionally difficult, to provide insulation from political pressure or retribution. The politicization of the civil service is an early sign of autocracy. But congressional Republicans, emboldened by unchecked power, have revived an obscure procedural rule that allows them to reduce a specific federal employee’s pay to $1, forcing the worker to work for free or resign. It is no small thing for government workers (who are, incidentally, disproportionately people of color) to stage a Bartlebean rebellion.

But our democracy may depend on it. And the moral fortitude of government workers depends on our solidarity, and the support of their unions and the few elected officials with any scrap of conscience or courage. Chapo Trap House podcast cohost Will Menaker expressed a similar idea on Facebook this weekend (the post was removed without explanation):

Every one of these objectively monstrous, cowardly and evil executive orders issued this week depend on the acquiescence of thousands of federal employees and bureaucrats to carry them out. They, and all of us, must get used to monkey wrenching all of this. If the Democratic leadership wanted to really be “The Resistance” they would hold a press conference and encourage all federal employees to passively resist or openly sabotage their new bosses.

Whatever our jobs, we must militantly prefer not to do anything our little despot decrees.