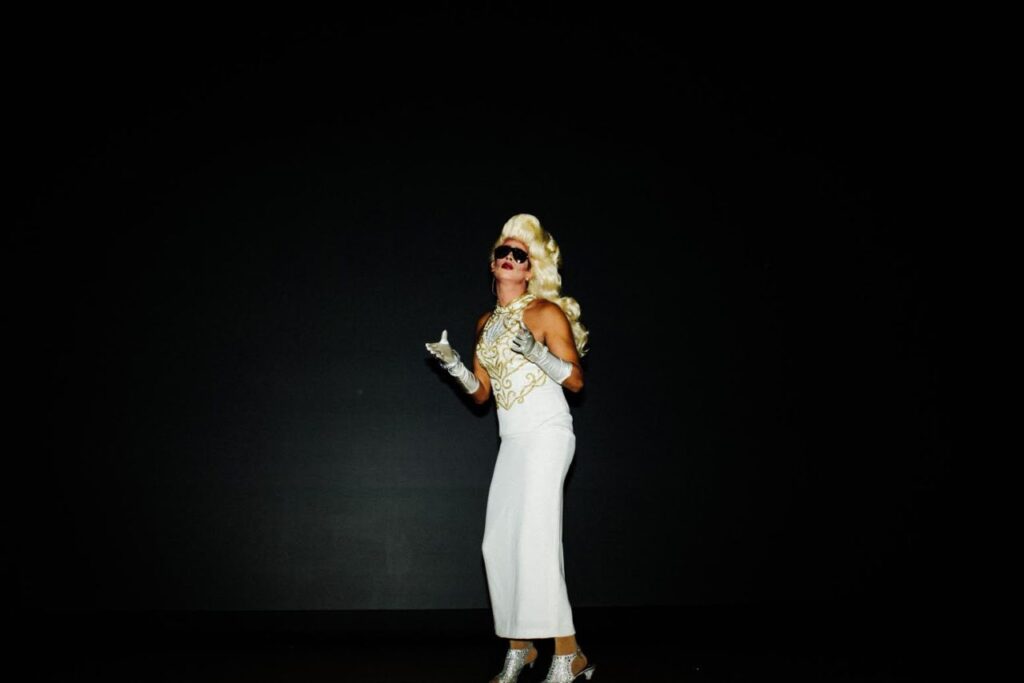

For the September 2016 stop at Louisiana State University of his Dangerous Faggot Tour, Milo Yiannopoulos is dressed as his drag persona Ivana Wall. Accompanied by a young squire, he teeters across the stage in a pair of sparkly high heels and a long white ball gown with gold brocade, carrying a gold-bound Bible. He removes his silver lamé cloak and white feather boa and adjusts the enormous blond wig perched atop his head, then waves his gloved hands to the ebullient crowd and proceeds to sing the national anthem and “America the Beautiful.” A slide on the screen behind Milo reads, “Admit it. Your dick is confused.”

Internet troll-master and technology editor for the far-right Breitbart News website, Yiannopoulos has built a cult of celebrity around himself as a breaker of liberal taboo and an advocate for what he calls free speech fundamentalism. In his articles, tweets, and lectures, he presents himself as a bold truth-teller, right-wing provocateur, and self-declared “faggot.” Like Cher or Beyoncé, his fame has grown so large that most people know him simply as “Milo.”

Milo is singular: an ultra right-wing pundit with a high-femme persona who is nonetheless embraced by a political bloc contemptuous of homosexuals and feminine men.

Though a fixture of the alt-right circuit since 2013, Milo was rocketed to mainstream visibility during the summer of 2016 when he was banned from Twitter for leading an online campaign of harassment against African American actress Leslie Jones. More recently, he became the center of controversy after it was announced he had signed a book deal with Threshold, the conservative imprint of Simon and Schuster, for which he received a $250,000 advance. Many bookstores are refusing to stock the book, accusing it of hate speech, and Chicago Review of Books has even taken the step of boycotting Simon and Schuster titles. Despite, or perhaps because of, this backlash, preorders from fans have thrust the title, Dangerous, to Amazon’s number one spot for political humor. These same fans recently flooded a survey on the website LGBTQ Nation to have Milo named its “Person of the Year.” Seemingly at odds with a movement founded on the hatred of racial, religious, and sexual difference, Milo has somehow been crowned the alt-right queen.

What makes Milo so vexing to the left and successful among young people on the right is the way he manages to utilize his “deviant” sexuality as a political asset rather than a liability. Milo’s rhetorical and aesthetic strategies are manifold: he adopts the argot of science and history in support of his claims about the supremacy of Western culture, but simultaneously asserts that we live in a “post-fact world.” He mocks the offended sensibilities of leftists who protest his campus appearances, yet uses the language of assault to characterize himself as an embattled champion. He effortlessly pivots from ridiculing his targets (fat people, Muslims, feminists) to asserting that his insults are in fact efforts to save these people from their brainwashing. If all else fails, he whips out a cock joke.

While there are parallels to be found between Milo and historical and contemporary fascist figures interested in homoeroticism, he remains singular: an ultra right-wing pundit with a high-femme persona who is nonetheless largely embraced by a political bloc synonymous with contempt for homosexuals and feminine men. Understanding the sources of his appeal is crucial to developing sophisticated insight into the way alt-right media—now the sanctioned news of the White House—uses spectacle and irony to persuade, bewitch, disrupt, and overwhelm the public.

Hitler with the bullet-scarred Röhm.

To understand exactly how Milo operates in a milieu shaped by fascist aesthetics—by which I mean both the visual tropes associated with Nazism, as well as the increasingly diverse visual strategies employed by contemporary fascists—it is necessary to examine the historical connections between fascism and homosexuality.

There is a long and grand tradition of masculinist gay fascism.

There is a long and grand tradition, in particular, of masculinist gay fascism. One need only look back to Ernst Röhm, a founder of the Nazi party and long-time head of its militia (the Sturmabteilung or SA), who was openly homosexual (as were many of his lieutenants) and advocated a militarized vision of masculinity based upon his experiences in World War I, in which “only the real, the true, the masculine held its value.” Influenced by the right-wing German sociologist and philosopher Hans Blüher, Röhm subscribed to a vision of fascism that embraced homosexuality as an acceptable and even necessary component of an all-male militaristic society called the Männerbund. Consistent with this line of thinking are Milo’s constant digs at “ugly” women, feminists, and lesbians, all of whom he considers baffling, useless, and pathetic. Like Röhm, Milo embraces a vociferous misogyny that suggests he would rather live in a world without women. However, the similarities between Röhm and Milo run out here.

With his large facial scars and barrel chest, Röhm’s hypermasculine appearance fell outside of Weimar stereotypes of how a homosexual should look and act (a stereotype that more closely resembles Milo). In Röhm’s view, conservative homophobia was a reactionary current in German political discourse that would be swept away when the Nazi’s rose to power. But the uneasy coalition of fascist homosexuals and homophobes would not hold, and ultimately Röhm’s homosexuality provided Hitler a ready rationale for his assassination in 1934 during the Night of Long Knives. After Röhm’s death, the Nazis increased the punishments for homosexual conduct under Paragraph 175 (a provision of the German criminal code), and initiated a public anti-vice campaign to rid the Reich of “homosexual contamination,” leading to the imprisonment and death of thousands of gay Germans. Yet Röhm’s long-term position of power and influence testifies to the complex and sometimes contradictory attitudes of fascists toward homosexuality within their own ranks.

Masculinist strains of fascism persist to this day, with the treatises of American gay white nationalist Jack Donovan perhaps best exemplifying this strange blend. In The Way of Men (2012), Donovan’s most popular book, he lays out his “gang theory of masculinity,” which relies upon “four tactical virtues”—strength, courage, mastery, and honor—that he claims distinguish men from women. Though Donovan skirts “the Jewish question,” he makes heavy allusion to Nazi symbolism, especially in his use of Germanic runes, and his writing is distributed by Counter-Currents Publishing, which exclusively sells Nazi- and white nationalist–themed books. Combining terms such as “tribe” and “barbarian” with imagery drawn from Crossfit, the Hell’s Angels, and Germanic mysticism, Donovan has concocted a vision of fascist masculinity based on a mythic past. Though Donovan’s fantasy may be backward-looking rather than future-oriented, like Röhm’s, it imagines a white and male-dominated society outside existing morality and sexual strictures.

In her 1975 New York Review of Books essay “Fascinating Fascism,” Susan Sontag interrogates what was then a growing trend within 1970s popular culture of reviving fascist imagery after three decades of total rebuke. Sontag begins by examining Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl’s photography book, The Last of the Nuba, in light of Riefenstahl’s involvement in the Third Reich. Sontag tracks a set of visual sensibilities across Riefenstahl’s filmmaking career, arriving at a kind of taxonomy of fascist aesthetics, which she calls “both prurient and idealizing.” For Sontag, fascist artworks share:

a preoccupation with situations of control, submissive behavior, and extravagant effort; they exalt two seemingly opposite states, egomania and servitude. The relations of domination and enslavement take the form of a characteristic pageantry . . . around an all-powerful, hypnotic leader figure or force. The fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets.

Sontag connects these obsessions with theatrical control to the rise of Nazi imagery in cinema, erotica, and fine art in the 1970s. Arthouse films such as The Damned (1969) and The Night Porter (1974) use the “supremely violent but also supremely beautiful” imagery of the SS to lasciviously explore the twisted psychologies of sadomasochism-loving Nazis; while films such as Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS (1975) epitomize the cresting wave of Nazisploitation, in which “far-out sex has been placed under the sign of Nazism.” As Sontag sees it, the unique appeal of Nazis in the context of sadomasochist fantasy is twofold: first, by the 1970s, fascism had become both novel to young people, yet also taboo; and second, fascism provides a readymade sexual fantasy that requires little imagination, “a master scenario available to everyone,” replete with a highly organized visual system: “The color is black, the material is leather. . . .”

Why did Nazi Germany become erotic?

From the arthouse cinema to the art gallery, Sontag’s analysis transitions from straight preoccupations with fascist aesthetics to the more pronounced and visible revival of these tropes within the gay community. She homes in on a self-portrait by Robert Morris that was used to promote a gallery opening of his work. Shirtless and oiled, Morris appears on his invitation wearing a Wehrmacht helmet and chains around his neck and wrists. As with Milo’s signature look, a pair of aviator sunglasses obscures Morris’s eyes in the photo. “Why has Nazi Germany, which was a sexually repressive society, become erotic?” Sontag asks. “How could a regime which persecuted homosexuals become a gay turn-on?” These are not unlike the questions the left has been asking about Milo, whose sexual identity and presentation leave him at odds with many of the constituencies in the alt-right.

A scene from llsa: She Wolf of the SS

A scene from llsa: She Wolf of the SS

Unlike Sontag, Žižek fails to understand that fascism’s aesthetics are its ideology.

Yet it is this very eventuality, of fascist rhetoric and imagery entering the mainstream through appropriation, that Sontag predicts in her analysis of Morris’s Nazi-inflected self-portrait. It is also precisely what philosopher Slavoj Žižek misses when he praises the band Rammstein for allowing audiences to take pleasure in the aesthetics of fascism without its ideology—failing to appreciate the degree to which fascism’s aesthetics are its ideology. Sontag writes of Morris’s portrait that he “is said to have considered this to be the only image that still has any power to shock: a singular virtue to those who take for granted that art is a sequence of ever-fresh gestures of provocation.” In this reading, Morris’s Nazi-themed image is merely an extension of other avant-garde art practices aimed at shocking the viewer into heightened experience. Yet Sontag senses that this move is a potentially corrosive aesthetic dead-end. “But the point of the poster is its own negation,” she continues. “Shocking people in this context also means inuring them, as Nazi material enters the vast repertory of popular iconography usable for the ironic commentaries of Pop art.” It has been more than forty years since Morris and so many others began reappropriating Nazi imagery for sexual and artistic purposes. Milo and his ilk are the end result.

The Emcee in Cabaret performs for a Nazi audience

Despite the long and entwined histories both of masculinist homosexual fascism and of fascist imagery being put to homoerotic use, most members of the alt-right remain hostile to homosexuality. Websites such as The Daily Stormer and The Right Stuff display an outright hatred of Milo, whose homosexuality they associate with femininity and a potential to undermine the bonds of masculine camaraderie. Women are meant to exist in a purely domestic sphere, and their only role is to produce and raise young fascists. This current of Neo-Nazism recuperates fascism’s emphasis on a vigorous, athletic homosociality defined by communal activity and sexual abnegation. As Sontag explains, “The erotic is always present as a temptation, with the most admirable response being a heroic repression of the sexual impulse.”

Violating the psychic and social boundaries of conventional masculinity is especially distressing to a community whose very existence is predicated upon the strict and sometimes violent enforcement of identity boundaries—yet gay fascists, of which there certainly must be many, continue to have sex with other men. This forbidden contact may occur in secret; it may arise out of “necessity” in all-male environments, such as prison or war; or it may occur as an act of aggression.

Exploring the motivations for gay fascist sex among Nazis and Neo-Nazis, sociologist Klaus Theweleit notes in his classic study, Male Fantasies Vol. 2: Male Bodies – Psychoanalyzing the White Terror (1989), the potential for these encounters to enforce power positions within a group. “The anus is identified as the site of aggression precisely because of its potential to produce vast deterritorializations” in unwilling victims while in turn producing “some form of wholeness in the persecutor.” One need only recall the shower rape depicted in American History X (1998) to understand the essential role of sex between fascist men as both a sexual outlet and a tool of violence and control. Yet as Theweleit notes, though homosexual intercourse is typically forbidden in fascist ideologies, the burden of shame is rarely distributed equally, such that “taking the ‘passive’ role in anal intercourse becomes a particularly pronounced form of degradation.” To be the top is to be a “moral degenerate” (as in the case of Röhm), but to be the bottom is unspeakable.

Milo’s tightrope walk relies upon the ambiguity of irony—he and his fans are just in it for “the lulz.”

Milo, then, occupies this unspeakable place: he is a self-avowed bottom who routinely celebrates the delights of being fucked—by a black man, no less, his supposedly black Muslim boyfriend (whose identity is perhaps Yiannopolous’s only secret). But rather than be embarrassed by his sexual predilections, Milo embraces his desire to bottom for black men, and uses media outlets such as Bloomberg and CNBC to trumpet it at every opportunity. As one example among many, Milo wrote in response to accusations of racism: “Racist? Me? I’ve had more black dick in me than the entire Kardashian family.”

At some events Milo furthers this femme bottom image by appearing in blousy shirts or Fire Island–ready tank tops, sometimes wearing feminine jewelry and makeup, or carrying a Louis Vuitton handbag. He may play up this queen act by swishing his hips when he takes the stage, or making droll comments about wishing he could have lived in ancient Sparta in order to participate in “sweaty man orgies.” (Nevermind that Athens would have been a more likely place to find these orgies.) “A faggot can dream!” he adds.

Yet in other appearances, Milo will wear a suit or sport coat and appear almost like a “coat-and-tie fascist” in the mold of Jared Taylor or Richard Spencer. Positioned behind a lectern, he can give off a vaguely professorial air. He embellishes his points by taking off and putting on his oval glasses, or looking down his nose into the eyes of his audience as he reads from his notes. In this mode, Milo is a trustworthy truth-teller. He is fond of making statements such as, “These are facts—you don’t just come here to be entertained—you come here to learn things.”

A meme of Milo from Know Your Meme

But the truth is that Milo’s fans do come to his events to be entertained, and it is Milo’s talent for entertainment that has allowed him to occupy what would otherwise be an untenable relationship to the alt-right. As he himself has acknowledged, his fans do not represent the entirety of the alt-right. Rather, Milo’s army represents a growing subset within the alt-right coalition, a group he refers to in “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide to the Alt-Right” as “the meme brigade.”

For the meme brigade, it’s just about having fun. They have no real problem with race-mixing, homosexuality, or even diverse societies: it’s just fun to watch the mayhem and outrage that erupts when those secular shibboleths are openly mocked. These younger mischief-makers instinctively understand who the authoritarians are and why and how to poke fun at them.

Sometimes called “cultural libertarians” or “free speech fundamentalists,” these memers, having emerged from the swamps of 4chan and Reddit, are united by a shared desire to say shocking and offensive things, and steadfastly believe that their right to do this is inalienable. The opening acts at Milo’s LSU performance testify to this confluence of provocation and aggressive humor. Following troll logic, Milo’s slogans, such as “Feminism is Cancer” and “Birth Control Makes Women Unattractive and Crazy,” are just jokes that uncomprehending liberal audiences mistake for serious hatred. He would have you believe that memes of big-nosed “Le Happy Merchant” stealing money from “Le American Bear”—or of a grossly caricatured black character named “Dindu Nuffin” falsely proclaiming his innocence—are not posted by actual fascists or white supremacists. Rather the people who disseminate these materials merely enjoy dressing up in the rhetoric and imagery of those ideologies because it upsets liberals (“lib-tards”) and mainstream conservatives (“cuckservatives”).

Milo’s tightrope walk relies upon the ambiguity of irony—he and his fans are just in it for “the lulz.” Wielding a male-inflected brand of cold, unfeeling humor, this subculture uses jokes as a means of shutting out political opponents, strengthening in-group social ties, and disarming the arguments of the left. As Ryan Milner notes in The World Made Meme (2016), “This amusement at others’ distress . . . can be employed both to commit great identity antagonisms and to defend those antagonisms as ‘just joking’ . . . revealing the emotional distance facilitated by such framing.” Milo’s provocations are subject to what Milner refers to as “Poe’s Law,” a widely held belief regarding the difficulty of distinguishing between earnest and ironic sentiments online, providing commenters and speakers with a permanent escape hatch: just kidding. IRL, Milo’s default style of delivery is one of catty bemusement, like a bargain-bin Oscar Wilde, such that everything he says can be positioned as a joke.

However, as Andrew Anglin argues in his Daily Stormer article “A Normie’s Guide to the Alt-Right,” not everyone on the alt-right believes they are joking. Anglin explains:

Some of the ways the movement presents itself can be confusing to the mainstream, given the level of irony involved. . . . The true nature of the movement, however, is serious and idealistic. We have in this new millennium an extremely nihilistic culture. From the point when I first became active in what has become the Alt-Right movement, it was my contention that in an age of nihilism, absolute idealism must be couched in irony in order to be taken seriously.

Following the unlikely lead of leftist community organizer Saul Alinksy, Anglin goes on to explain that the alt-right’s aesthetic strategy has departed from old-fashioned fascism in order to succeed in the digital age. In a turn few could have imagined, Anglin ends the essay by laying out his plans to utilize the techniques of left-wing Jewish intellectuals to disseminate seemingly ironic Neo-Nazi memes.

Despite the fact that Anglin states that the alt-right repudiates gays, Milo’s use of his homosexuality nonetheless works along the lines of the trollish, mimetic logic that Anglin lays out. His alt-right fans flock to his events not in spite of his sometimes outrageous appearance, statements, and flaming sexuality, but rather because of them. Like the Emcee in Cabaret, performing his deviance to the delight of a Nazi audience, Milo’s carnivalesque presence within the sphere of the alt-right is exciting and transgressive, signaling the inversion of the established order. In another context, Milo’s personal identity could be cause for his audience to assault him, yet on the stage, making fun of the alt-right’s enemies, Milo’s contradictions are permitted and celebrated as “edgy.” Even the commenters on Breitbart seem to recognize the strategic benefits of Milo’s contradictory persona:

“People like Milo are exactly what the Conservative movement needs. Using ridiculous characters and personas on stage is a tactic that works. It attracts attention, and gets the young people to listen to things that they need to hear.”

“This Milo cat is the best thing that could have happened to Trump. It completely destroys any credibility from the Bully Left that Republicans are bigots, racist, sexist, homophobes, etc.”

The first commenter notes the utility of Milo’s antics for publicity and propaganda, while the second commenter highlights Milo’s value as a token of right-wing tolerance. Milo can say things like “faggot” because he is gay; therefore his fans are permitted to use the same language, as they could not possibly be homophobes themselves by virtue of adoring him. This reinforces the “it’s all a joke” logic that allows so many on the alt-right to playfully dabble in hate speech while retaining a sense of moral integrity. Objectors are then positioned as humorless, oversensitive snowflakes.

At the same time, in this permissive atmosphere of transgression that is the comment threads on Breitbart, commenters express more than just admiration or vicarious glee at the trouble Milo causes for liberal enemies. Going further, many of these commenters talk about Milo in the language of desire.

“Milo is a gorgeous bitch! He is beautiful and angular. His intellect is like Einstein only more fabulous!”

“I luv him and I am a straight man.”

“not my proudest boner”

“#MiloSexual”

These pseudonymous comments reflect a cohort of fans who seem fixated on Milo’s appearance. Many begin with the caveat “I’m straight” but then proceed to catalog Milo’s physical virtues. Whether these comments are earnest expressions of latent homosexual desire or low-grade trolling is almost beside the point, as their very presence is still a remarkable anomaly. While other alt-right figures may be the objects of private desire for readers and fans, you will not find these kinds of declarations under old Ben Shapiro articles. In a strange turn, the comments sections of Milo’s Breitbart articles, while still full of hate speech, sometimes directed at Milo, have also become a space for the discussion of same-sex desire between men.

Like “Daddy Trump,” Milo has found a way to convert his relationship with his fans into cold, hard cash.

Taking these comments a step further, Milo’s theme song, “Milo, My Love,” amplifies this discourse. Written by Rockie Gold, the song is played as Milo takes the stage during his tour. It offers a list of Milo’s accomplishments and virtues, with a notable line arriving in the second verse: “And he’s rocking True Religions ’cause he’s so hot.” The heavily autotuned chorus consists of “Milo, my love / Milo, my love / Yeah we doin’ it for Milo,” repeated over and over.

But if singing their love for Milo isn’t enough, his fans can express their adulation by buying his merchandise. On his web store you will find shirts with tags such as “I’m with the Patriarchy,” with an arrow pointing to the wearer’s crotch, and “I Pledge Allegiance to the Fag.” Referring to the “Dicks Out for Harambe” meme, a recently added shirt is emblazoned with the command “Dicks Out for Milo.” You can even buy framed posters of Milo’s face, and a pillow with an image of Milo in the shower marked by a pair of red lips in the lower corner. This item is called “Wet Dreams.” In each case, buyers of Milo merchandise are relating themselves to him through a supposedly ironic, yet explicitly homoerotic object or garment. This garment stands in for Milo’s physical body, allowing fans to maintain two fantasies at once: I want to fuck Milo, and I can also be like him. To show his fans how it is done, Milo even models this dynamic of subject and ruler by consistently referring to Donald Trump as “Daddy.” Just as Trump is Milo’s “Daddy,” Milo casts himself as both a ruler and love object. And like father, like son: Milo has found a way to convert this relationship with his fans into cold, hard cash.

The problems of Milo’s paradoxical position—sex symbol to a political movement that alternately embraces and repudiates him—remains unresolved, and that is the way he likes it. Milo denies his membership within the alt-right, but is perhaps the movement’s most visible proponent. To maintain his celebrity, Milo has to stay outrageous, desirable, and singular. Though he sells a shirt on his web store with the line “Milo in Training,” for his magic to work there can be nobody else like him on the alt-right. Adopting an identity coherent with his political ideologies would spell the end of his career.

Warming up the crowd at LSU Baton Rouge, Milo as Ivana Wall asks, “Do we have frat boys in the hall?” Loud grunts and cheers. “Do we have any homosexuals?” A smattering of applause. “No, not so many—good.” Milo smiles impishly. After making fun of their southern accents and thanking Professor Benjamin Acosta for his introduction, Milo lays out the terms of his talk: “I’m Milo, the internet supervillain who only needs one name. I’m the aforementioned Dangerous Faggot, thank you so much for coming out to see me.” He holds back to let a few people applaud, clasping the podium with both gloved hands. “It is my duty, honor, and privilege to speak about dangerous topics on American university campuses around the country, at those schools which are brave enough to support free speech.” Milo pauses again to survey the audience, prolonging the silence for maximum dramatic effect.

“And those that aren’t get it in the neck.”

Independent and nonprofit, Boston Review relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate or become a member.