You're in the family kitchen. Mom and Dad have been arguing—no, fighting—for over an hour, louder than TV. As you overhear them (you can't avoid it) you realize that anything either parent tells the other can be reinterpreted, misinterpreted, and turned against its speaker. In the meantime, TV commercials invite you to reinterpret their endless pitches. ("Buy Wonder Bread, one familiar ad implores." But what makes the bread wondrous? What will this white bread make you wonder about? Could it be one of the ancient world's Seven Wonders? Would Mom or Dad even understand questions like those?) As you begin to transcribe bits of their quarrel, bits of your TV show, bits of commercials, you discover that the language in each sounds like language in all the others, and it all seems designed to sell you stuff—designed, that is, for the benefit of the seller, and without your own interests in mind. As you try to put the bits together, you see how hard it has become to trust any of it; could all language be this unreliable?

You go on making linguistic collages like this, adding verbal armatures of your own. In them you explore your growing suspicion—of yourself, of your parents, of money, of the whole American system in which everything that seems to matter comes with a sales pitch and a price tag. Your growing fascination with rearranged words seems to give you the power to see through things, to find the machinery or the hidden contradictions under all kinds of economic-linguistic-artistic façades. After you've been doing this for a while, you realize (emotionally) what you might have known (intellectually) all along: these see-through dialects of fraud and bad faith, these corruptible, companionable, always-already-commercial phraseologies, are all there is. If you want to express any feeling, articulate any reaction, you will have to do it in the same languages you have been mocking and disassembling: there is no authentic alternative, no uncorrupted language reserved for true sentiment. Moreover, you will have to do it while mocking those languages, since your sentiments and reactions now seem as suspect to you as anyone else's: you, too, live in the culture of cash-credit-and-carry, and your skeptical x-ray vision cannot be turned off.

• • •

Though bits of it derive from her brief memoir True, the foregoing is not a history but a fable, designed to help new readers comprehend—and enjoy—Rae Armantrout's strange, original, and corrosively self-critical poems. Armantrout grew up in suburban San Diego; her unsympathetic parents devoted themselves to evangelical Christianity and to cowboy stories. ("My mother has always been a myth-maker, of sorts," Armantrout writes in True; "I began to experience all this myth-making as repulsive.") Throughout high school she and a friend pursued fantasies of life as Mexican outlaws; in college, at San Diego State University and at Berkeley, she enjoyed the late sixties counterculture, encountering her future husband, Chuck Korkegian, and her first poetic collaborator, Ron Silliman. With Lyn Hejinian, Barrett Watten, and others, Armantrout and Silliman helped set up the Bay Area small-press and journal scene of the 1970s, in which "Language writing" took shape. Armantrout moved back to San Diego in 1978, when she was expecting a child; she has lived there ever since.

A Wild Salience collects writings on Armantrout's work by San Francisco and San Diego comrades, academic critics, and other admirers (among them Robert Creeley and Lydia Davis); it also includes two interviews (with Hejinian and editor Tom Beckett) and new poems. As these writings show, Armantrout shares the thematic concerns of other Language writers. She considers commodification, cultural capital, and the links between power and taste. She undermines our expectations about identity, unity, prose sense, logical and emotional direction; sometimes she identifies those expectations with economic or sexual inequity. (Her work, she says, can "focus on the interventions of capitalism into consciousness.") Armantrout's ear, her choice of poetic models, and her unusual temperament—a kind of universal solvent for words and ideas—together let her embody all those concerns (and more) in remarkable, compact poems.

Armantrout's stanzas and lines derive from William Carlos Williams, Emily Dickinson, George Oppen, Lorine Niedecker, Robert Creeley, and perhaps Denise Levertov (Armantrout's teacher at Berkeley)—in that order. "Williams was the first poet I read seriously," Armantrout tells Hejinian. Williams and Dickinson together taught Armantrout how to dismantle and reassemble the forms of stanzaic lyric—how to turn it inside out and backwards, how to embody large questions and apprehensions in the conjunctions of individual words, how to generate productive clashes from arrangements of small groups of phrases. From these techniques, Armantrout has become one of the most recognizable, and one of the best, poets of her generation.

Extremities (1978) shows Armantrout's interests before she had gathered them into a style. These earliest poems (like those of her San Francisco friends) often depend on the effects of collage: some look like collections of scraps of paper (resonant scraps: "the charmed verges of presence"). One early poem deserves special attention:

We know the story.

She turns

back to find her trail

devoured by birds.The years; the

undergrowth

These six lines—the whole of her poem "Generation" already exhibit features that typify Armantrout's poems. She invokes a story, or a constellation of stories, we already know (the babes in the wood, Hansel and Gretel) in order to say that it's probably not the whole story. Her short lines and jagged rhythms give the breaks maximum prominence. Those breaks, in turn, emphasize partial syntax and semantic alternatives: "she turns"…into a swan, or a tree, or to religion? No, she merely turns back. This stranded, frustrated, and frustrating protagonist, caught in the midst of a story with an obscured beginning and no good end, makes available (without enforcing) a feminist moral: why do our fairy tales like to put women in trouble? At the same time, Armantrout's sparse arrangements of isolate phrases reminds us how much of this "story" we tell ourselves, how much what we think we learn is what we already "know."

A less guarded early poem, "Tone," follows Williams's stanza form and Williams's interest in small objects: one section reads,

Not pleased to see the

rubber band, chapstick, tin-

foil, this pen, things

made for our useBut the bouquet you made

of doorknobs, long nails for

their stems sometimes

brings happiness

Like Williams, Armantrout appreciates small, ignored, manmade things, and feels relatively little attraction to nonhuman nature. Unlike Williams, she's anxious about "use." "'When names perform a function,'" a "stubborn old woman" explains in a poem called "A Story," "'that's fiction.'" Armantrout's wary, oppositional temperament, her resistance to fictions and functions, was hers from the start: all she had to do was find her own forms for it.

By Precedence (1985) those forms had arrived. The quotation-filled, deeply unpredictable stanzaic poems which dominate her work from that volume forward explore her suspicions of everything, including her own modes of suspicion. Often they seem to begin after somebody else has stopped talking. Asked to speak first, these poems would not know what to say: they, and she, need received forms and ideas to work against. Consider "Double," the first poem in Precedence:

So these are the hills of home. Hazy tiers

nearly subliminal. To see them is to see

double, hear bad puns delivered with a wink.

An untoward familiarity.Rising from my sleep, the road is more

and less the road. Around that bend are pale

houses, pairs of junipers. Then to look

reveals no more.

Armantrout seems here to describe her return to San Diego. More than that, though, she describes the (to her, deeply unreliable) process of looking and making. Poetic vision is always double vision, impressions of fact always mediated by anticipations of form; but here these anticipations seem to obstruct, or even to prevent, any knowledge of a real house or real road.

Armantrout's characteristic tones involve exasperation, or tense anticipation, or knowing, beleaguered menace. "Go ahead," a recent poem asks, "say anything," as if it already knew what we might say. If this unease means that her poems depend on the expectations she likes to undermine, it also gives them their peculiar negative powers, as in one sequence called "Fiction": "When the woman's face contorted and she clutched the railing for support, we knew she would die for this was a film with the set trajectory of fiction." Against these predictable trajectories Armantrout can set infants and toddlers, who give her poems the alien, nearly-incomprehensible perspectives she seems to enjoy: "She planned to give birth to a girl who resembled her husband's family or perhaps no one at all. An utterly new countenance."

Of course, no language, no sentiment, can remain "utterly new." We do not make up the words we use—instead we take in and send out language in mostly-unexamined pieces, "regular self-deluded everyday phrases," as Rachel Blau du Plessis puts it in A Wild Salience. Almost anything we say can thus sound (to a sufficiently guarded ear) like a set of unacknowledged quotations:

When he awakened

she was just returning from

one of her little trips.

To learn to read Armantrout is to learn to hear the quotation marks around that last line, and then to ask whether quotes belong on the other lines too. It is also to learn to separate speech from speaker, denotative meanings from ulterior motives, a tactic that seems récherché until the same poem offers examples:

Now the boss could say

"parameters"

and mean something

like "I'll pinch."

Here—and throughout Armantrout's work—the unreflective use of ordinary spoken language proves inextricable from economic exploitation (so that Armantrout seems in exposing the first to attack the second): the boss can repurpose his words, and his employees, because he's the man who signs the checks.

Almost as much as she likes implicit quotations, Armantrout likes oxymorons, couplets, or sentences that catch us in bad assumptions: "'Ha, ha, you missed me,'/ a dead person says" ("Home Federal"); "Moments later / archeologists found him" ("Covers"). Archaeologists find people "moments later" all the time (when, for example, their children get lost in crowds), but it's hardly in their line of work, which involves finding things, and people, centuries after their loss. Armantrout's lines imply a puzzle or paradox, one we must overrule our expectations to process. Category mistakes, bad puns, cartoonish coincidences—these spark poems, too, because they let Armantrout suggest that all symbols are as arbitrary or unreliable as those the mistakes expose. In this vertiginous mode, Armantrout can sound less like other "Language writers" than like an improbably terse stand-up comic:

I made only one statement

because of a bad winter.Grease is the word; grease

is the wayI am feeling.

Real life emergencies orflubbing behind the scenes.

As a child,

I was abandonedin a story

made of trees.

The poet-critics Steve Evans and Jennifer Moxley joke that Armantrout keeps getting labeled "the 'lyrical' language poet"; she herself has shown a weighty ambivalence about "lyric" as a term for her work. If a lyric poem is a short work whose form embodies a single consciousness, then it's hard not to think of her work as lyric. Yet she seems to pry open or disassemble the coherent self and consistent voice on which most versions of "lyric" depend. "Statement" equates Armantrout's "given name" with the tags she gets at a hospital, or from a child—"Thirty-One Year Old / Prima-Gravida, // The Pokey-Puppy." Our sense of self comes (it implies) not from any reliable voice or consistent being-in-the-world, but from slippery guesses and temporary hypotheses. "Identity is a form / of prayer" she conjectures in a poem called "My Associates." Armantrout sometimes finds a coherent "I" or a reliable "you" as hard to credit as a beneficent deity. The same poem continues:

"How do I look?"

meaning what

could I pass forwhere every eye's

a guard.

"I think that if I didn't 'write against norms," Armantrout says in one interview, "I wouldn't be writing." Her self-making (not only in her poems but on the evidence of her autobiography) has been a series of resistances to easier, less guarded versions of world and self. Interiority, for her, consists in a demonstrated capacity to interrogate the images the culture throws at us, the images we discover—to our distaste or surprise—inside ourselves. In True, Armantrout recalls taking LSD and discovering her own distinctive persona, a psyche distinguished at its core by its mistrust of discoveries, distinctions, cores:

…I clearly saw that most of what I called "me" was a system of defensive barricades (the sort of "tough-mindedness" and macho posturing I'd attributed to my old heroes…) and that what was inside them was what?—shame? fear? my mother and father? This was a premature encounter with "deconstruction," I think, but one which I almost immediately began to find interesting….In retrospect, I think that I did have a "real" self, of a sort. I was the person who would think such an experience was interesting and would want to do it again. I was also the one who couldn't stop trying to talk about it.

Her ambivalence about "a 'real' self" gives her works much of their compelling oddity. Armantrout likes to watch—and resist—the way her conscious mind and her ingrained tastes segment a chaotic and potentially continuous world into discrete parts. ("I too / am a segmentalist," a recent poem admits.) She notices, and objects to, the almost involuntary force with which she gives almost all her poems closure: even when they involve quasi-independent sections, they end with the finality of a slammed car door.

Some of those closures come through accounts of dreams. "A real dream," Armantrout writes in "Birthmark: The Pretext," becomes "interesting….to the extent that there is a stranger in my head arranging things for me." The poet in "The Plot" "can't get to sleep" because her temperament prevents her; she remains

conscious of the metaphoric

contraption; it's too jerky,

too equivocal to suspend you

Descent into sleep is for Armantrout a surrender to the cultural unconscious; though the realm of dreams may feel like a foreign country, its language and assumptions turn out to be those by which Americans live, rendered bizarre because newly exposed. "The Plot" concludes:

Why is sleep's border guarded?

On the monitors

professional false selves

make self-disparaging remarks.

There's a sexy bored housewife,

very Natalie Wood-like,

sighing, "Men should win"—

but the only thing that matters

is the pace of substitution.

You feel like trying to escape

from her straight-arrow husband

and her biker boyfriendYou can't believe

you're on Penelope's Secret.

A suitor waits

for ages

to be hypnotized

on stage.

What sort of world is this, in which everyone stands around like a TV host, or like an actor in an old film? It is the world of sleep, where America's mythopoetic icons return to Armantrout in dreams. This dreamscape (driven by "substitution"—what Freud called "condensation and displacement") turns American women into Penelopes, forever waiting for their man, and American men into self-deceived Homeric suitors, doomed if Daddy comes home.

Armantrout's ideas, and her odd, brusque sounds, can make it harder to notice her other talents, and in particular her keen eye. Her lines slow perception into separable units, like frames of a film; in doing so, they can scrutinize and demystify it, or render it newly vivid. "Leaving" explores the Pacific coast using techniques A. R. Ammons might have recognized:

With waves

shine slides over

shine like skin's

what sections

same from same.

In the best of the academic pieces in A Wild Salience, Bob Perelman identifies Armantrout's roots in Imagism: her poems at once depict objects, as accurately as they can, and show how any depictions rely on the assumptions (never neutral, never fully self-justifying) we bring. "Disown" quotes such assumptions, then trashes them in order to see old suburbs anew:

"Run down," they say,

"buildings."Wave of morning glory

leaves about to break

over the dropped plastic

bat, the empty shed.

Williams fans may notice the break on "break"; they may notice, too, how Armantrout's terse revaluation of urban disarray derives from the earlier poet's championing of sheds, stoops, bits of green glass glimpsed in the street.

George Lakoff and other cognitive scientists have proposed that our daily thoughts and decisions depend (as Mark Turner put it) on "small spatial stories": we make room in our schedules, allow someone intoour lives, move up in the workplace. At least since Engines (1983), her prose collaboration with Ron Silliman, Armantrout has liked to literalize and exaggerate these metaphors: "To understand is to 'follow'" (Engines); "Bird calls rise / and drop/ to an unseen floor" ("Theories," italics mine). What if these "small spatial stories" prove as deceptive as the Home Shopping Network? "When I'm metaphorical / I'm happy," Armantrout says in "Ongoing," though she knows she of all people cannot stay happy: her example of "metaphorical" mindset comes, in fact, from a children's book (The Little Engine That Could):

When an effort

was a small engine,then I loved it

like a mommy.

"Metaphor should make us suspicious," Armantrout tells Hejinian, "but we can't do without it." Nor can Armatrout do without dramatizing her suspicions. Often she juxtaposes symbols high and low, respected, trashy, or trivial, in order to show that all of them work the same way. In "Here," she writes: "It's supposed to be beautiful / to repeat a motif / in another medium," so Armantrout repeats a symbolic motif in whichpercussion represents strength:

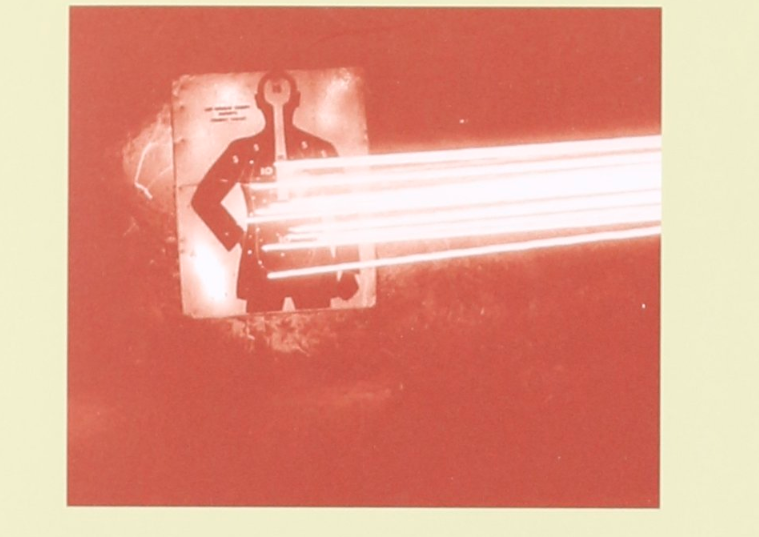

There's a boy down the street,

firing caps

as my son didwhile a church plays

its booming

recording of chimes.

The boy's spontaneous play repeats the action of earlier, older boys; the church's "booming / recording" strikes an atheistic listener as both boastful and doubly fake—not just a false God, but false bells to boot, no better than the "[b]ig masculine threat" (to quote an earlier poem) of the boy's cap gun.

Those sardonic (and partly spondaic) lines about booms and bangs should also call attention to Armantrout's ear. Her irregular, two-to-four-beat lines and stanzas not only match the intellectual processes she describes (doubt, disbelief, resentful or respectful endurance); they also match the rhythms of that process (two steps forward and three steps back; denial, consideration, belief, denial). In "Sets" an elegant arc-shaped stanza follows

Time's tic:

to pitch forward

then catch "itself"

again.

These successive approximations of fictions are for Armantrout the only way in which we perceive anything. Even those perceptions become suspect for Armantrout (in an odd echo of Bergson) because they will always involve metaphor—forward and back (which turn time into space), "pitch" and "catch" (which invoke gymnastics or baseball).

Armantrout's jagged lines, always ready to switch from one idea back to the next, also let her juxtapose treatments and figures other poets would have to handle separately. The title poem in Necromance (1991) considers a woman in a mysterious "land" (perhaps California) who

washed

dishes in a black liquid

with islands of froth—

and sang.

Many poets could portray a beleaguered housewife, an oil spill, the land of the dead, or a Homeric siren: Armantrout's trick is to do all four at once. In doing so she also asks how much her word choice, our word choice, creates the events and reactions we try to interpret. Even looking and naming seem to her dangerous: the names we give to things and roles and people allow those things and people to be controlled, to take their place in markets and other systems of (conscious or unconscious) exploitation. (Later in that poem "precision / is revealed as / hostility.") The poem feels, by the end, like a defense of the sirens, as if they had developed their fatal singing out of a justified annoyance at sailors who, whenever a ship passed, whistled and stared.

Necromance also highlighted Armantrout's terse but unmistakable feminism, which during the 1980s led her to scrutinize and disassemble constructions of beauty and femininity. Armantrout's focus on gender, and her drive to demystify, also led her poems to highlight the practical tasks, the so-called 'women's work,' without which symbolic orders and life-plans would wither; "Articulation," for example, announces:

The one making coffee

or doing the driving—that is the real

person in your life.

Now that one is goneor has tagged along with you

like a small child

behind Mother.

For a supposedly abstract (and a genuinely difficult) poet, Armantrout has quite a lot to say about motherhood, both (in Adrienne Rich's phrase) as an experience and as an institution. "Crossing" considers the assumptions ancient myths and children's games might share:

According to legend

Mom

sustains the universe

by yelling

"Stay there

where it's safe"

when every star

wants to run home

to her.

What does this unsentimental analogy say about "primitive" peoples? about mothers? about our reliance on other, supposedly grown-up, leaders? "Getting Warm" could not exist without Armantrout's feminism, nor without her years of child-rearing; the poem compares her own poetics to primary language acquisition:

If she's quiet

she's concentrating on the spaces

between cries, turning

times into spaces

……………………………………………

She is in the dark,

sewing, stringing holes together

with invisible thread.

That's a feminine accomplishment:

a feat of memory, a managed

repletion or resplendence.

"She" may well be a baby, or a poet (writing Armantrout's sort of verse), or anyone (especially any woman) performing a demanding, "invisible" task.

• • •

Armantrout has lately become less interested in debunking per se, and more interested in embodiment, memory, and time—though these are changes in emphasis and degree, visible only on repeated rereadings of her recent work. The end-stopped couplets of "Manufacturing" dissect and examine visual experience, comparing its snapshot moments to the uneasy ongoingness of thought, hearing, and recollection:

The eye asks if the green,

frilled geranium puckers,

clustered at angleson each stem,

are similar enoughto stop time.

It has asked this question already.

How much present tense

can any resemblance make?

Most of her poems after 1989 include at least one of these key words:parent/mother/mommy, memory/remember/recall, repetition/repeat/recur, nostalgia, person, self. The words, and the topics they represent, interact: as we grow up, we learn (if we can) to depend on memories of our own experience, rather than reacting against our parents'. At the same time, our visions of parenthood and childhood change, especially if we become parents ourselves. In "Native" (also a poem about the suburbs) Armantrout notices these processes in her own life and asks (with a chilly pun on "dead") where it ends:

At what point does

dead reckoning'snet

replace the nestand the body

of a parent?

To enjoy Armantrout one has to like her choppy surfaces, accede to her demands that we read slowly, and appreciate her overarching worries about figuration, mediation, symbolism-in-general. At the same time, Armantrout's poems offer psychological truths and sad ironies wholly separable from her commitment to difficulty and disjunction. Ever been part of a couple who felt like this?

Each finds

his mate pre-dictable

but believes his own

rigiditymust excite

his partner

Note the pun on "rigidity"; note, too the abnormally rapid, short (even for Armantrout) lines—as if she knows we've been there too. Her recent poems seem more willing than the rest to let in such clear psychological language, perhaps because they are less angry and more sad, less aware of injustice than of loss. ("From the first / abstraction," the last poem inVeil has it, "loss / is edible.") Poems about Armantrout's dying mother (most from 2001's The Pretext) can make isolated images yield clear, almost Larkinesque ironies:

"Schools of fish are trapped

In these pools,"

Say the anchorsWho hang

On nursing home walls.

Armantrout's poetry of retrospect, cast back over her own life and career, can be even sadder, and clearer. "Our Nature" rebukes

our self-consciousness

which was reallyour infatuation

with our own fame,

………………………………..

our loyalty

to our old gangfrom among whom

it was our natureto be singled out

Parallels for this sort of self-appraisal arise not in Silliman, nor in Stein, but in Stevens ("As You Leave the Room"), Matthew Arnold, Louise Glück.

Though lines like those will gather new admirers with wider exposure, most of Armantrout's poetry is not for everyone: it's usually dissonant, almost never mellifluous, unambiguous, or strongly narrative. The sounds and tones of its stanzas are memorably crafted, but its large-scale arrangements can seem opaque: it can be hard to know why four segments, say, of a thirty-two-line poem require the order they have and not another. Armantrout's current influence on younger poets grows in part from her merits, and in part from their disillusionment with other available models (other "Language writers" included). It grows, too, from the timeliness of her obsessions: Armantrout has become the poet of our contemporary frustration with what we might call the social construction of everything. After Freud, Gombrich, Derrida, Foucault, Bourdieu, the Voter News Service, and the last few wars, we know how little we can be authors of ourselves, how much we act in scripts we cannot write (let alone direct). That feeling of helplessness may not be new (it's arguably in Homer) but our constant consciousness of it is; so, perhaps, is our awareness that the scripts we live out have no cosmic authority, reflect no good we have not made.

"[A]n objection / so pervasive," (Armantrout says in "Light"), "cannot know its enemy." We could pose the same objection to her: does she really want to live without symbol systems? To this her poems reply: do you really want to keep trusting the symbols you see? If we cannot be authors of ourselves, Armantrout's harsh, funny, self-conscious poems suggest, we can be our own demanding critics, seeking closer accounts of whatever we've done. Few readers—few poets—feel as strongly as Armantrout the relentlessness of our given scripts; few resent them as productively as she does. Her best poems' titles recap her obsessions: inVeil those poems include "Double," "Through Walls," all the selections from Necromance, "Covers," "A Pulse," "Leaving," "Greeting," "Birthmark: The Pretext," "Articulation," "About," "Here," "Theories," "Whole," "Our Nature," and "Manufacturing." It may be objected against them all that if nothing can be done about symbol systems in general, if we are doomed to live amid them, we might as well learn to like them, rather than constantly trying to pry them open or to investigate their wiring. It would be just as pointless to object, against Hopkins or Housman or Hardy or Williams, that we can do nothing about growing old.