Kim Kyung Ju's poetry operates on the threshold where “the living are born in the dead people's world, and the dead are born in the living,” a world where no one seems to belong. Destructive forces like social isolation and disease are often transformed into gateways to the sublime—zones of verisimilitude, where human action takes on the mythic and chaotic quality of nature, and in turn, nature acquires human fragility. Hence the title of his first collection, I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World. Perhaps it is this conflation of human agency and natural order that has led some critics to call Kim's poems “both a blessing and a curse to Korean literature.”

Not yet forty, Kim Kyung Ju has already published over a dozen books of poetry, translation, and essays. He is also a teacher, playwright, events organizer, and has worked as a copywriter, ghostwriter, and writer of pornographic novels. His first book of poems is one of the most popular and successful books of contemporary poetry in Korea. Already in its thirtieth edition and currently being translated into English, I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World is an achievement not only for its technical innovation and transgressive content, but also for its ability to explore the weight the contemporary world bears on the human soul. Given that we live in an age where our attention is increasingly divided into smaller and smaller fractions of time and the corresponding social problems and anxieties that arise due to new and digital forms of instant social interaction, perhaps there is no more important task for poetry than to ask questions geared toward the eternal.

The following interview took place the day after Korean New Year at a small cafe in the trendy neighborhood of Hongdae. The artist Kim Sang Do, known to some under his pen name Baba Kim or English name Balloon, helped interpret the following conversation.

Jake Levine: You've been called a progenitor of the New Wave movement in Korea. What exactly is New Wave poetry and how is it different?

Kim Kyung Ju: About twenty years ago, a Korean critic put out a book where he described the drastically different style young Korean poets were using to break with tradition in Korean poetry—both in form and content. Instead of poems about nature, history, realism, etc., younger authors at that time were interested in fantasy, drama, the grotesque, and describing a counter culture. The younger writers writing in this style represented the New Wave movement, which occurred around the same time and had to do with similar cultural issues as the movie Oldboy. I mean, how could we not change? Similar to the Beat movement in the fifties in America, we needed alternative methods of narrative and poetic structure. Our work raised controversial questions about the role of poetry in Korea: “New Wave, is it good or not good?”

I want to talk about the world as a ghost.

Korean society developed really quickly. Especially with the rise of the Internet. People who live in societies that change that rapidly suffer from a kind of schizophrenia—multiple personalities. So outside you could be a respectable citizen, but as soon as you walk into an internet cafe you are the devil incarnate with Devil 666 as your handle. When our previous president committed suicide, it was a reflection of the reality that we are not a united country or people, that we are really isolated from each other and have dangerous and violent sides to ourselves. We suffer from dissociative disorders, where our awareness, identity, and perception of reality often disrupt and break down. Of course I'm not only talking about Korea. All industrialized societies have these problems. So the New Wave addressed this phenomenon. Oldboy did it through fantasy, originally as a Japanese manga. But this fantasy was the only way to express our psychological reality. This was the new state of the world.

If I lived in Japan and had been born in Japan I think I would have been an animator. This is because animation in Japan is the way artists tackle problems in society. But in Korea traditional forms of literature are the way our society best addresses these social phenomena. I mean when we were young, people respected you if you wanted to be a writer. We used to share our writing with one another and that was how we associated with each other. But nowadays young people don't do that. Teenagers who write are considered loners, like they have some kind of social problem where they can't interact regularly with society. When they write they are considered to be self-indulgent. If you were young and said you wanted to be a writer, people would probably think you have some kind of mental disorder. Because of PC games. Pop culture. Dramas. K-Pop. No one respects writers. Generally people think literature is outdated and so isn't an important thing to do.

JL: Because it is not important to mainstream society, how do you see Korean poetry in terms of its role as a counterweight to mainstream Korean culture?

KKJ: As a general rule, poetry in society today compared to the role it played in Korean history is not that different. Poetry's role is to speak against the government, the acting regime, the popular culture. Popular culture, kitsch culture, is the polar opposite of poetry. If you tried to map out how the culture of poetry works in Korea, we could discuss several things. First as counter culture, poets write about sensitive political issues in a direct way other mediums can't address. As opposed to pop culture, when mainstream society tries to look for “originality” or to gain perspective on global issues, they refer to poetry because poetry consciously addresses issues and global concerns in a direct way.

JL: Speaking of which, in your work there is a common theme of alienation, social and political alienation, where characters are driven to extremes like suicide and abortion, that I think represent social taboos in Korea. For example, one of your poems, “The Night Text Messages from the Young Girls of the Sugar Factory Roll By,” has a young girl employed by the sugar factory. Her suicide is foreshadowed by the death of her pet bird.

If holding the bird that died with its eyes open, all night you must fly following the floating snow in the dead bird's eyes and that's life.

It is only through the death of her bird that she becomes complicit in her own death, and yet “that's life” perfectly illustrates the flat tone or complete acceptance of the event as natural. To me this poem represents the way many South Koreans have been willing to accept social problems like the high rate of suicide, extreme alienation, alcoholism, social exclusion, and economic inequality as natural byproducts of economic growth.

KKJ: Yes, I want to talk about the world as a ghost, to create the atmosphere and point of view with the feeling that I am dead. Realism talks about the world as we see it. For example a ninety-year-old lady crosses the road when the signal is red. So she probably knows and senses the rules but is no longer interested in them. She is living in her own world beyond reality. I am interested in capturing that world. That disposition. I mean, what is the poetic? Poetics? When I first started writing, I thought that, within a tradition, people have to look for the poetic in our everyday life, in nature and through relationships. But I realized over time, that's not what I should be doing at all. What I needed to find was the poetic state within myself, and in that way, I became a lens to make the world poetic. We must create a poetic language to capture what our language cannot normally express. And if you are a poet and use poetic language then you have found your poetic state. So what the reader is ultimately finding is not the world through poetry, but the poet in his/her poetic state in his/her language. For instance, when I was traveling and I heard a passage from the Koran, I had no idea it had to do with Islam or the meaning or history, but I understood the feeling and knew it was prayer.

JL: In your book, there is an epigraph that reads, “I am a ghost. Such a loneliness cannot exist.” Often your poems attain the sublime through alienation and social exclusion. What is that in the service of?

KKJ: That epigram is from the poem, “Dry Ice.” When you touch dry ice, you feel extremes of hot and cold at the same time and then it just disappears. That's what I want to invite the reader into, that quality of loneliness. In the poems and plays that I write there are three emotional states that I am interested in representing: shame, vanity, and guilt. Because these are states people usually keep secret, I want to use them to make the world more vulnerable through the hidden language of these secrets. I pick and choose between the three and build pieces around these states. I mean, if you are a writer, it is the most important thing to ask yourself: What is my shame? Where is it from? And how does it build up? Like Walter Benjamin, Kafka, Mallarme, there are many great writers who made themselves vulnerable to vanity, shame, and guilt.

JL: On the subject of shame, guilt, and vanity, I also know you have a background writing pornographic novels and ghostwriting. Could you talk about that a bit?

KKJ: Yes, this is very important. I am not ashamed of being a ghostwriter at all. I always put it on my resume. I got credit as a ghostwriter and so I still feel like that is my true identity.

For six years I was a ghostwriter. I did it to survive. And at that time I was very ashamed by a whole lot of things I did just to pay rent. As a poet you write poems and build a book and publish it and it is totally different. So as a writer I could feel very fractured, like I am a copywriter, or a ghostwriter, and write smut and I write poems, like I have multiple personalities, but I view myself as one writer who writes all these things.

My pornographic novel alias was based on Don Juan, but Korean, like Kim Don Juan. I got plenty of pen letters. It was really surprising. I was like, what kind of people actually read this shit? Teenagers? But not at all. People like construction workers, hard-working people who receive decent wages but have no time for a social life. And lonely people like quilt-making grandmas. It was very surprising! So I was like, it could be complete garbage, but it helps the loneliness of these people, so it isn't totally garbage.

When I wrote this work, I was living in Seoul and I didn't have any friends and I was also very alone. Because of the nature of the work I was writing, everything was mass syndicated in Seoul, through leaflets, or commercials, or through advertising, and because my words were reaching all these people, it was like I was embracing all the lonely strangers in Seoul through writing.

At that time my editor was an actress whose only guideline was that whatever I write had to be able to turn her on. Really, turn her on. It was very difficult. We fought all the time. She'd shake her finger and say Bad Bad Bad.

But what's really important is that we recognize all the ghostwriters and the job they do for society. There are many ghostwriters. And it is respectable work.

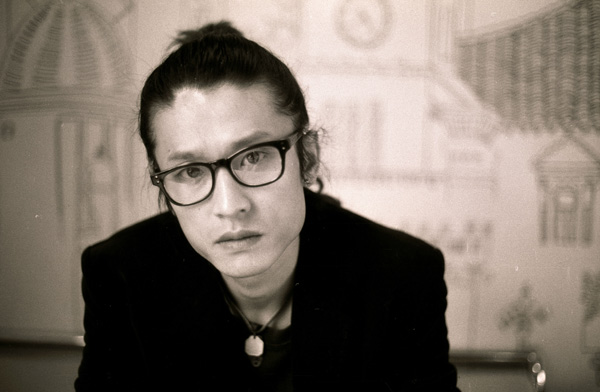

Photo courtesy of Kim Kyung Ju.