Tiny Windows

Duncan McNaughton

Auguste Press

Who knows or can speak of Duncan McNaughton and his poems: of the Boston-born poet (1942), now living in San Francisco, editor of the two 1970s poetry journals Fathar and Mother; founder and director of the Poetics Program at the New College of California; master teacher in the 1980s with that other Duncan (Robert), among other extraordinary teacher-poets who refused academia or whom academia refused (David Meltzer, Diane di Prima, Michael Palmer); author of a never published dissertation on Shakespeare’s sonnets, along with eighteen books of poetry, which, by and large, have never been reviewed, relics of the generation of slow hand-made small press poetry books mostly out of print.

And so who knows, who notices, that to speak of Duncan McNaughton’s poetry is to go against the current of poets rambling in poetic rhetoric about the role of poetry in today’s social-media world, as if, McNaughton wrote in a March 3, 2006, letter to the poet and critic Dale Smith, it is “a matter of the poem and the poets having to become ‘better’ communicators or to come up with means which generate wider social attention to them.” Such exertions are not for McNaughton. Instead, he critiques discourseas a cultural practice serving systems of power; in this sense he sees the poem as disobedient to that enterprise. Words do or don’t do the work of the poem—they are, as Jack Spicer said in his second letter to Lorca, “what we hold on with, nothing else.”The work of the poem, McNaughton writes, “is not in any sense a job for rhetoric, in order to gain efficacy of persuasion, to gain social affect i.e. power. . . . Language and discourse, specifically generated by the advent of writing itself, are in the agency of power. . . . It is like Alice Notley said, words aren’t language—they never were.”

McNaughton’s sense of what words are about, what the poet can do with them, is captured in Charles Olson’s description of the poet as an “archaeologist of morning.” At SUNY Buffalo in the 1970s, McNaughton became part of the lineage of poets who have “dug” Olson’s poetics, working with Olson’s colleague, the poet-scholar Jack Clarke after Olson’s death. As Smith, who in turn studied with McNaughton at New College of California in San Francisco, writes:

Clearly situated within the tradition of Modernism, and opposed to the total bullshit castration process encouraged by Postmodernism, McNaughton’s work achieves a testament of personal observation embedded in a trans-historical tendance of the imagination. It’s Olsonian, and behind it, like so much else, he owes a great deal to Pound. He’s also unapologetically Romantic, in the tradition of Blake, D.H. Lawrence, Nerval and Robert Duncan.

Smith is describing the work of a writer looking back to the future. He discovers history for himself anew, following the word’s etymology in the Greek istorin, “to discover for oneself,” one of Olson’s informal directives for the poet. The poet is on a dig, breaking ground, which at times hides or occults a buried reality. The common facts right at our feet can be transformed through the words of the poem into magical or mythical or theological narratives: poem-stories structured by names of sites and people. Olson learned the possibilities for this kind of telling from Victor Bérard (among others), who had speculated that some myths in Homer’s Odyssey were guided by Phoenician maritime logs, which named the islandoccupied by volcanoes they passed “the island of the one-eyes,” and which Homer transformed into the tale of Odysseus and the Cyclops. This is what the poem’s words as names can root out: the news of the Phoenician place names, buried in Semitic etymology, long ago become fable or story; the Phoenician facts on the ground (or on the water), motivating the wanderings of a Greek or, as in James Joyce’s transmutation of the story, a Jew in Dublin.

McNaughton’s poems return us to these kinds of rootings and wanderings: names are always shifting on his journey, with the lyric and epic voices of Sappho, Homer, John Keats, Olson, John Wieners, Ed Dorn, and Robert Creeley in the wings.Take this excerpt from the poem “Lost and Found,” with which Tiny Windows begins:

Bring me the telephone number of Juan,

that’s John in Spanish, Garcia for I

have piers to be set and if I do it

myself neither they nor I will be on

the level, and bring me Greer with a beer

for my wife and my life for Jack Kerouac

If you listen closely you can hear a similar shifting of pronouns in Robert Creeley’s famous poem:

As I sd to my

friend, because I am

always talking,—John, I

sd, which was not his

name, the darkness sur-

rounds us, what

can we do against

it, or else, shall we &

why not, buy a goddamn big car,

drive, he sd, for

christ’s sake, look

out where yr going.

The impulse in both poems is to travel in Keats’s mysteries and doubt, in negative capability. It is to be on Kerouac’s road and “to look out where yr going.” These poems are always acts of discovery. They are places where being is explored across what is near and familiar, where the “darkness surrounds us,” where “the hand is blackened that reaches through”:

So, here I am again on

the threshold glancing again into

eternity’s open doorway. The hand

Is blackened that reaches through. Old now,

futile, my blackened art. To be is a

verb, it means to be. You could call it a

dream of ethics. You could say, Waiter, there’s

a Jew in my soup. Trust me. Dining

bemusedly with fiends and demons

drifting downriver aboard the Fidèle.

McNaughton’s “blackened art” turns voice into persona: a trickster voice, dead serious and deadpan comic, on the level and off-balance, as we go along for the ride. “Trust me” is uttered in the suspect spirit and tone of Melville’s Confidence Man and his crew of avatars, “fiends and demons/drifting downriver aboard the Fidèle.”

On this trip, let’s allow for what some might see as McNaughton’s bad form if only for good measure. For example, in “So, here I am again on / The threshold glancing again into / Eternity’s open doorway,” the word “again” appears twice in successive lines. This flies in the face of the creative writing teacher’s dictum—“don’t repeat the same word if you can find another”—a short-sighted “organic” truism that McNaughton de-naturalizes. Things work differently here among the small words, which, Louis Zukofsky claimed, are “weighted with as much epos and historical destiny as one man can perhaps resolve.” In McNaughton’s poem, the prepositions—“on,” “into”—resonate, but without resolution, so that the word “again” can, must appear twice. McNaughton measuresthe meaning of these lines in relation to our hearing the “n” sounds and syllables: “again” leads to “on,” leads to “glancing again into / Eternity’s open,” taking us by echo into the open door of darkness. As Robert Duncan spoke of the “tone-leading of vowels,” here we have the tone-leading of consonants, as the path of creativity takes shape in the parts of the poem building upon each other.

To speak of McNaughton’s poetry is to go against the current of poets rambling in poetic rhetoric about the role of poetry in today’s social-media world.

Consider that first poem, “Lost and Found,” which addresses the very public legal battle over control of Kerouac’s estate (which he left to his mother, who left it to his third wife, in a will that the trial’s judge, George Greer, ruled was forged). McNaughton mock-rhymes the literary circus: “bring me Greer with a beer / For my wife and life for Jack Kerouac.” But even without knowing the context, the “foreign” references become familiar in the way they are used: off the cuff, on the cuff, as if we’ve been invited to the bar to talk it all over. All we need to recognize is the casual hello/goodbye tone in the phrase “Adios Caballito” from “Adventures in Dating And Doom.” Or is it the goodbye/hello tone, from the first lines—a sigh on the passing of time absurdly dressed up in the worn out signs of old clothes, what McNaughton names “the Pants of Time”:

Now that success seems unlikely and

the Pants of Time, to borrow the image from

haberdashery, trousers for a once

presentable gentleman, are threadbare,

has the moment finally arrived when

one must say Adios, Caballito!?

To enter this poem’s fond farewell thinking is to agree to be taken: you will allow the poem to guide you anywhere, on its terms, to arrive who knows where and when. Seamlessly moving through time and space, you traverse moods and speculations on existence: from the formal temporal sigh of regret for a life without success presented as old school or gentlemanly in “threadbare” “trousers,” to the beautiful possibility of an art that can “call one home.”

McNaughton’s poems call us: from one to another they visit us from everywhere, almost at once. They look out. They tour, they span. They evoke multiple times and moods and geographies and jargons and voices. We are brought into the middle of micro-encounters and conversations we had not previously suspected we were a part of, implicated in someone else’s arrival in the poem. The feel at times is light and joking, at times cosmographical and existential—the species’ psychological and social landscapes on view, on call.

Yet McNaughton’s landscapes are not scenery. Instead, they evoke the same sense that Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) described in Charles Olson’s work, where landscape becomes “what one can see from where one is standing.” This sense encompasses Olson’s working class Gloucester destroyed by urban renewal, “when all is become billboards,” as well as Baraka’s blighted Newark; and Edward Dorn’s rural Illinois, where families, to make ends meet during wartime, succumb to one of the country’s largest corporate retailers, its catalog market forces, recalled in his extraordinary poem, “On The Debt My Mother Owed to Sears Roebuck.” Like Dorn, McNaughton shapes a poem about how class is absorbed into the landscape, asking the reader to reflect on what “class” means.

In “Hand in Hand,” for example, McNaughton writes the narrative of a tailor and his mendings at a time in history when this “civilized” practice and its attendant order of affairs is about to unravel. Here is the first part:

Carlisle, the tailor, though otherwise a

clumsy man, sat taking his ale and a

helping of rhubarb-serviceberry pie.

The last of an overcast foggy day

added to the dimness that had settled

on his thoughts. The discreet Chinese bell

That hung from his shop door seldom chimed any.

Sartorialismo, along with so

much else that had once made humane sense,

had been tossed to the dustbin. Those days were gone from

Saskatoon. Bankers had become worms, the barons of commerce

and politics, worms,

the gamblers and sharp gusanos all. The

old class of gentlemen brought in their shirts

for the collars to be turned, their fabrics

were fine, buttonhole stich was respected,

waste hadn’t become a virtue. Appearance

had been understood to be metaphor.

Can the end of craft—a tailor’s or any other—signal a civilization undone? McNaughton rimes—to borrow Robert Duncan’s spelling and with it his suggestion that between words there are harmonies in meaning and syntax as well as in sound—these figures with “the / old class of gentlemen who brought in their shirts / for their collars to be turned.” With that riming, an expression emerges: the worm had turned—a reversal of fortune. The question this resonance raises is: for whom? We are given the romance of a charmed, bygone landscape with a Chinese bell on top of a tailor’s shop and the tailor with “the Cree woman who looked after them.” We might ask, how do these things go hand in hand: the couple is moving there, arm in arm, under the whims of bankers? On the one hand, there is a unique appeal, a strange quaintness in the old class of gentlemen in fine fabrics visiting the local tailor. But at the same time, there arises a deep aversion to the speculator financial maggots who compose the feeder economic class that occupies the place. In the midst of all this, the gorgeous couplet, which closes this poem and reflects the couple, the tailor and the Cree woman, opens our eyes to a landscape in which their image is frozen in time: “in cold weather they skated together / arm in arm, when the pond was a mirror.”

It is, finally, this vision of place that opens to another in the poem following it, called “Ghazzah.” The poet moves us from old Saskatoon to ancient and present Palestine, where a similar ideal remembrance, in this case perhaps a beach romance, is being upturned, this time by Israeli territorial imperatives:

Do you remember walking barefoot out

across the sandbar at low tide toward

sunset’s magical colors? I do but

I can’t remember when. This city, this

beach, they’ve been here 5000 years. I don’t

know who or what I was that evening.

Just a guy too lucky to care. I can

still see that sunset sky. I could still see

you but for the sons of bitches in their

fucking sanctimonious F16s.

Note the conversational, almost innocent tone of this poem, which turns on a dime to rage, as the poem ends and events become too logistically real for comfort, the girlfriend of “a guy too lucky to care” bombed on a beach in front of him. The poem struggles “between all that constitutes the agency of the meanness of power”—with that “sunset sky [and] the sons of bitches in their fucking sanctimonious F16s”—and “all the agency that labors on behalf of the agency of beauty and knowledge” (letter from McNaughton to Dale Smith), of people “walking barefoot out / across the sandbar at low tide toward / sunset’s magical colors?”

But for McNaughton, the poem’s struggle ultimately leaves power behind.This renunciation is an affirmation of his lineage and a recognition “in whose or what’s behalf one has given one’s life to the poem”:

When Homer looks in the mirror he sees Sappho— to get around to what lyric is and is doing. She is the defining mistress of lyric. It starts, as all great poetry does, with the endeavor to, and finally succeed in, recognizing in whose or what’s behalf one has given one’s life to the poem. . . . The poem finds its audience; its audience finds the poem…. In the game of the poem, and I mean ‘game’ just as a 1000-year-old sufi means that term, power is not in any way what’s up.

Beauty is what’s up. Knowledge is what’s up. Just like Keats says.

What’s up with McNaughton’s poetry and its lineage is news not often told. It carries no status, no powers of persuasion, no social affect, no awards, no teaching positions—because it is hidden outside an academy monetized and professionalized by MFA programs. So it needs to be said that there was a time when poets could be read as belonging to occult schools. “The School of Boston,” wrote Gerrit Lansing in 1968, “in poetry, middle this century, is an occult school, unknown.” And Michael Seth Stewart has more recently added, “The School of Boston” was not only “fascinated by the occult,” exploring hermeneutic, magical traditions and practices of poeisis, but was also “occulted, hidden on the back side of Beacon Hill while Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and their ilk were garnering attention in the more upscale parts of town, institutionalized at the private hospitals.” “The School of Boston” was, in terms of class and power, an outlier “school” and, in terms of politics and poetics, unaligned with the academy, from the wrong side of town. In 2015, Lansing’s cohort can include Duncan McNaughton, of Boston and San Francisco, still to be found out.

These poets once stumbled upon each other’s work in bookstores and within the small magazines like Fathar. In these pages they found ancestors—Olson, for example—to turn to. A chain was strung out and one generation was bound to the next through these publications. The poets inside them sought each other out through letters, and the poets reading them submitted to these magazines as a rite of passage to become one more link in the chain. It seems this chain of transmission has been broken. Where “the chain of memory is resurrection” (Olson), there are poets like McNaughton who need to be dug up, who are part of a tradition in which we need to see ourselves—much in the way, McNaughton writes, “when Homer looks in the mirror he sees Sappho—to get around to what lyric is and is doing.”

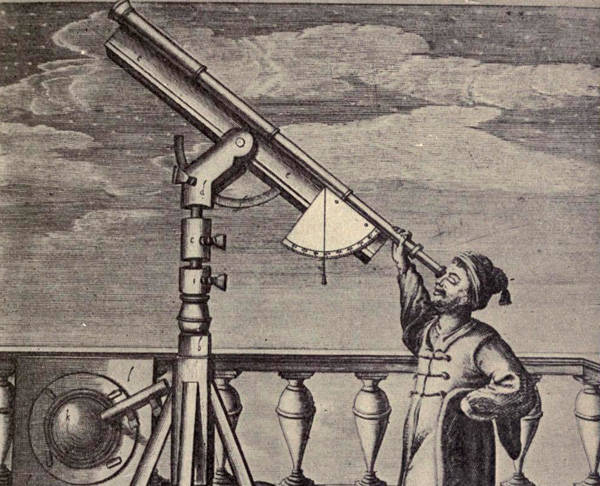

Poets in such a tradition look out and locate poetry, as McNaughton does, precisely in its comprehension of the cosmos and among those poets who compose in the traditions of “the Homeric opus, which was into Roman times understood, by those who could, precisely as of ‘Homer was an astronomer’ (Heraklitos)—that is, a work of cosmology rehearsing, in its fashion . . . with all else it so marvelously brings forward, thousands of years of cosmological observation” (McNaughton letter to Dale Smith). “I picked a career in poetry,” McNaughton writes, “because poetry told me it was the sole means by which I could educate myself.”And true to his life’s practice of self-teaching, and to what Robert Duncan called “Writing [as] first a search in obedience [to the poem],” the poems in Tiny Windows strive towards obeying “words and talk . . . in the agency of beauty and knowledge . . . gates into finding out.”