Ten Thousand Lives

Ko Un, translated by Brother Anthony of Taize, Young-moo Kim, and Gary Gach

Green Integer, $14.95 (paper)

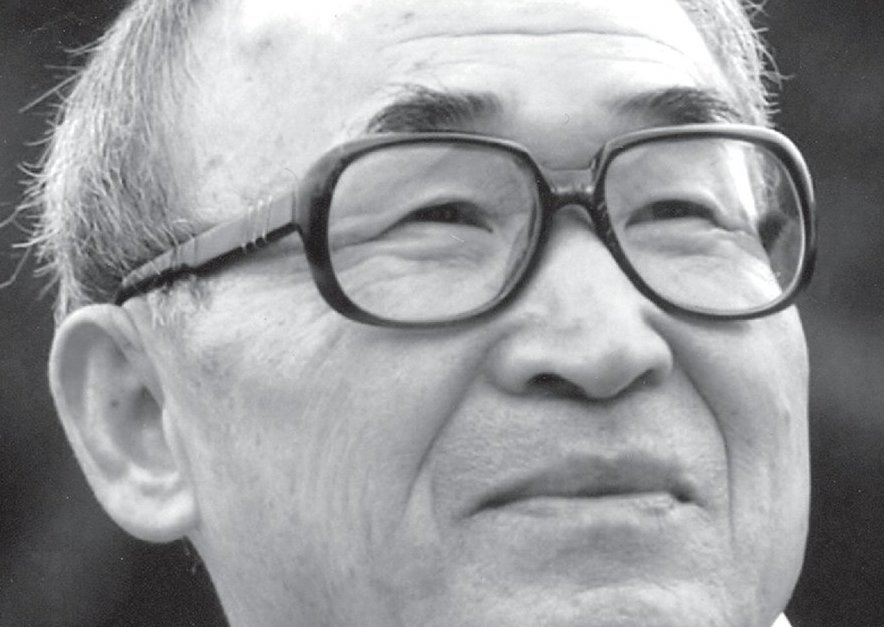

Sentenced to life imprisonment for opposing South Korea’s military dictatorships in the 1970s, the poet Ko Un decided to write a series of poems chronicling the lives of everyone he had ever come into contact with. This Green Integer paperback, with a wonderful introduction by Robert Hass, brings together a selection of these portraits, most of them about a page in length. But the most striking portrait is the first: a photograph of Ko Un himself, whose expression of implacable and jolly fortitude sets the tone for the collection. Alert, bracing, immediate, and folksy, Ten Thousand Lives is a gathering of people—mostly village folk—that does not discriminate between riffraff and bigwigs. The exclamatory and often tinny voice of the speaker is never brutal, but consistently achieves a brightness of tone that exceeds clarity and teeters on the brink of the surreal. In “The Wife from Kaesari,” the culturally situated restraint of a village woman is treated to such brightness: “Knowing no eloquence in her lifetime, / she was incapable of any decent last words. / She was more or less heard to say / the lid of the soy-sauce jar up on the terrace / ought to be opened to the daylight / and also, it seems, / that the lining in father’s jacket ought to be replaced.” There is no way of getting around the deeply moral impulse that governs these compositions, but a poem like this one doesn’t allow judgment to be its focus. Conscience, especially in the earlier poems, acts more as a structural principle than one that makes the poet—or the persons he memorializes—reflective. Meeting a handsome murderer in jail, Ko Un writes, “That bright smile / those graceful movements / undoubtedly the star in some movie / only it was as if somewhere in his life / the seed of that dreadful act had sprouted / and grown up, taking his body for humus.” Indeed, each person in Ten Thousand Lives seems both excruciatingly present and terrifyingly absent. More than, or at least different from, a collection of poems in the traditional sense, Ten Thousand Lives is an uncanny testament to the brutalities of history and a nervy attempt to remind us that individuals are worth dignifying.