The Complete Poetry: A Bilingual Edition

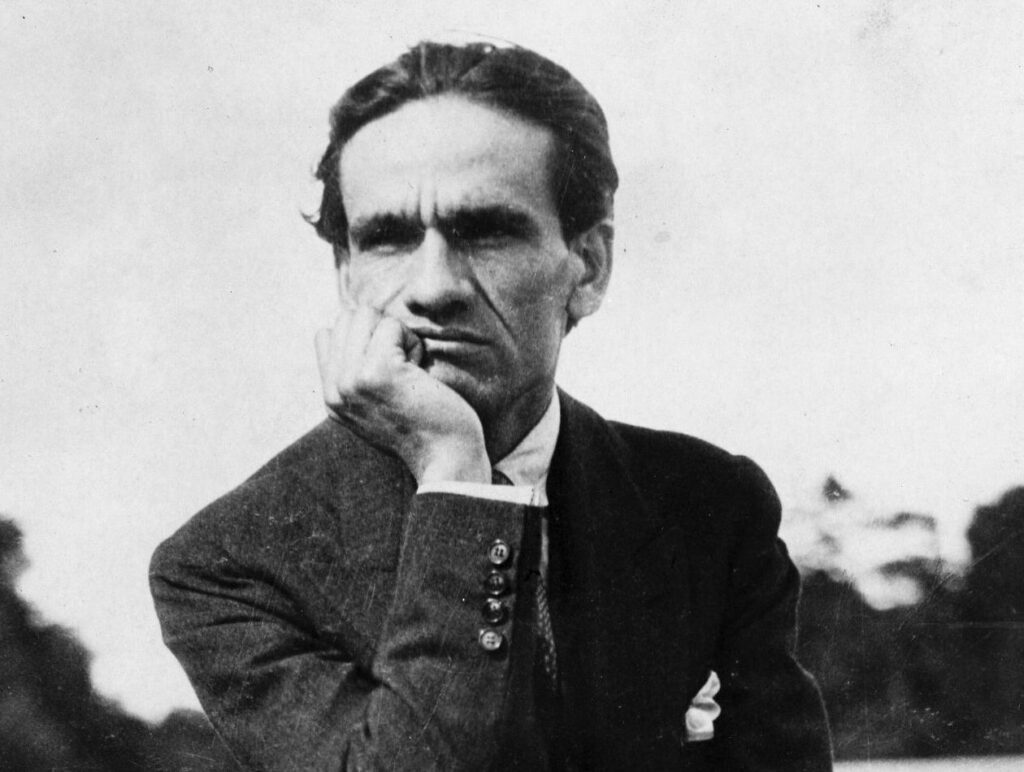

César Vallejo, edited and translated by Clayton Eshleman

University of California Press, $49.95 (cloth)

In many ways, Vallejo can be touted as a bona fide modern mystic, perverting the language of the Catholic Church with the hope of achieving more personal, idiosyncratic spiritual experiences in his poetry. The result is most often deeply hermetic, either mysterious, or just mystifying. “Penetrate the ecumenical mary. / Oh saintgabriel, make the soul conceive,” he writes with such self-seriousness it’s hard not to laugh. Yet when he points his “deicidal finger” at God in one poem and, in another, writes, “Don’t I know that never does one say ‘never,’ on one’s knees?” the reader may get the sense that the only true believer is the blasphemer or heretic who rages against the inadequacy of his faith. In “Love,” a convincing early poem that is uncommon in its rhetorical clarity, Vallejo closes with this exhortation: “Love, come without flesh, from an astonishing ichor, / so that I, in the manner of God, may be a man / who loves and begets without sensual pleasure!” Equally direct and moving are the “Songs From Home,” a series of poems about his family from Black Heralds, a collection whose integrity and narrative intensity make it hard to pull isolated lines. But Vallejo’s early clarity is quickly mussed in favor of the exuberant experimentalism that finds its apotheosis in Trilce, with its personification of numbers, deliberate misspellings, and overall zaniness. (It is also in Trilce that the poet dispenses with self-denial and abandons himself to sexual pleasure.) Throughout his work, Vallejo delights in acts of transgression, as when, in “The Nine Monsters”—one of the Human Poems, a dazzling catch-all collection of posthumously published poems—he confesses a desire “to put a little bird on the evildoer’s nape.” As Vallejo becomes less Catholic and more catholic, embracing an improbably wide range of human experience—he “wants to help the killer kill”—the reader may excuse his gluttonous relationship to suffering. If the reader still has reservations, Vallejo at least anticipates them in “Violence of the Hours”: “In the world of perfect health, the perspective on which I suffer will be mocked.”