More than 1.5 million children currently have a parent in prison; for 94 percent of these children, that parent is the father. In 1999 an estimated half of men incarcerated in federal prisons and 55 percent in state prisons had children under age eighteen. Sixty-two percent reported monthly contact with their children by letter, phone, or visit; a majority, however, have never been visited by their children since entering prison.

There are strong temptations to overlook or dismiss the parental interests of incarcerated fathers: they are often not married to the mothers of their children, they cannot financially support their children, and their criminal activity makes them bad role models. Moreover, children grow and develop rapidly, and extended lack of contact may foreclose the possibility of resuming a prior relationship after prison. Maintaining one’s role as a father in prison, thus, is deeply vexed.

Vexed, but not impossible. The fact that people imprisoned for crimes are by definition not ideal fathers does not mean that they are not fathers. Even when they are in prison they can have significant responsibilities, as nurturers and as emotionally important figures in their children’s lives. And fulfilling those responsibilities may have considerable consequences for their own successful return to ordinary life.

Public policy has a large role to play in making this happen. Policies on the assessment of child support obligations can promote or undermine the roles of economic provider, just as policies on parent-child contact (letters, phone calls, and visitation) make an essential difference to the role of psychological caregiver. The first reflects traditional notions of father as breadwinner, while the second suggests traditionally female forms of care-giving, such as attentive presence and emotional support and affirmation. More supportive policies of both kinds during incarceration help to foster rehabilitation and reintegration into the community, and are also requirements of justice.

To be sure, paternal involvement is not the only important value. Both parents have responsibilities of economic and emotional support. And men’s parenting from prison must not undercut the authority or well-being of the mother (or other adult) providing daily care. Responsible fatherhood involves willing two-way cooperation; it is collaborative parenting. And because children’s well-being is affected so directly by the well-being of their caregiver, good policy should not challenge but rather support the custodial parent—usually the mother—and her relationship with her children.

States often impose financial obligations on fathers in prison. According to some estimates, 20-25 percent of all incarcerated men are under child support orders. In 2005 these incarcerated fathers accounted for 16-18 percent of the $107 billion in child support arrears nationally. Many fathers who enter prison are poor to begin with and have not proved themselves able to support their children even before prison. Several studies—from Massachusetts, Colorado, and elsewhere—find that, on average, inmates with child-support orders owe about $10,000 at the time of incarceration. And since incarcerated fathers as a group earn well under the minimum wage—about $50 a month—few are able to contribute more than a symbolic sum to child support.

To some extent, the imposition on incarcerated men who have limited opportunity to earn income is an example of the neo-liberal impulse to privatize responsibility for the welfare of citizens, including children. But while government should be more generous in supporting children and caregivers, child-support obligations should not be abolished; child support payments are financially consequential for all poor families, constituting about a quarter to a third of the income received by families below the poverty line. And child support acknowledges and reinforces one aspect of paternal responsibility. What is not acceptable, however, are current state policies imposing child support obligations that incarcerated men cannot fulfill.

Yet many states have policies that impose child-support orders on incarcerated men while setting wages that make it impossible for them to meet their obligations. In states that do not suspend or modify the accumulation of child-support debts, fathers leave prison with anywhere from a 60 percent to a 200 percent increase in child-support arrears. This accumulated debt is not the result of indifferent work habits (showing up for work in prison is mandatory) or refusal to pay support (prison accounts are often garnished); it is simply the result of the disparity between state-set “awards” and state-set wages. Under these policies, the men can only fail.

The state’s role in turning fathers into failed breadwinners is obscured by the general rationale for state policies that prohibit adjustment of child-support obligations while fathers are in prison. Roughly half of the states consider incarceration to be volitional—an act by an individual offender who knew or should have known the consequences of his chosen behavior—and treat incarceration as a period of “voluntary unemployment.” Of these states, about twenty-one take a “no-justification” approach: incarceration is not a good reason for eliminating or modifying child-support orders, and child-support obligations are burdens the prisoner should have anticipated.

Some states that reject the no-justification model use a “modification” approach that encourages prisoners to contact the courts and seek some temporary reduction of their child-support levy on the pragmatic but untested grounds that if less is required, more will be paid. Other states have asserted a clearer “principled” position: Oregon, the only state whose Constitution requires all inmates to work, exempts inmate accounts from garnishment up to the sum of $2000 on the argument that a “person returning to the community without any funds leads them to revert to criminal activity.”

Policies that treat incarceration as voluntary unemployment are, then, neither universal nor immutable, and there is significant variation in case law in the different states about whether the commission of an offense leading to incarceration constitutes voluntary unemployment. The 1998 Alaska case of Bendixen v. Bendixen gives the flavor of this disagreement. In that year the Alaskan Supreme Court overruled a Superior Court judgment that had likened incarceration to voluntary unemployment because “crimes are willful conduct, just as voluntary unemployment is willful conduct.” The Supreme Court observed that serving jail time is “seldom a goal of criminal misconduct” and that, absent such intent, child-support obligations of an incarcerated individual should be based on ability to pay. They require the father to pay only the minimum support obligation of $50 a month—no inconsequential sum given that the better paid industry jobs in Alaska Corrections at the time paid about fifty cents an hour. Although child support policies continue to vary by state, Senators Evan Bayh and Barack Obama have cosponsored and introduced legislation in Congress, that would prohibit states from considering any part of a period of incarceration as voluntary unemployment that would disqualify the parent from obtaining a review and adjustment of a child support obligation.

Such legislation would bring us closer to European social policy. The German Civil Code bases child-support requirements even for incarcerated parents on a person’s ability to pay. Provided there is no immediate connection between the felony and the desire to avoid support obligation, the operative assumption is generally that incarcerated individuals will not be in an economic position to pay child-support payments. In Sweden a prisoner acquires child-support debt while in prison but is considered unable to pay while incarcerated. After release, a plan to pay support is then set based on whatever sum an ex-offender can afford—a sum that may take a lifetime to pay.

As these examples demonstrate, American states are not passive bystanders in a process of “fatherhood decertification” of men in prison. By piling on penalties—by requiring imprisoned fathers to accumulate child-support arrears impossible to cover with prison wages—the state undermines the fulfillment of obligations after release. In some instances men who are in arrears in child support break off contact with their families because they do not want to be harassed about payment and because they want their children to be eligible for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families benefits. Allowing individuals to emerge from prison with $16,000-$18,000 or more in debt, the state in effect encourages newly released prisoners to seek illegal employment, renew criminal activity, or “tax” family members who feel pressured into making loans to the former inmates.

Levying excessive child support also undermines men’s social citizenship and in a few instances nullifies their right to vote. Current law in Tennessee allows individuals convicted of felonies (exempting certain crimes) to register to vote upon release, but individuals who continue to owe money for child support payments are disenfranchised. Such payment-dependent voting eligibility looks little different from debtors’ prison or the Constitutionally proscribed poll tax of an earlier era.

Although Tennessee’s constitutionally-inscribed requirement is now unusual among the fifty states, it is not the only state in which child-support obligations can affect voting rights. Nine states condition the restoration of voting rights on an applicant’s full payment of at least some of the court-ordered costs associated with conviction. In Florida the “clemency” rules on rights restoration say that the “Executive Clemency Board will consider, but not be limited to, the following factors when determining whether to grant clemency: (1) The nature of the offense, (2) Whether the applicant has any history of mental instability, drug or alcohol abuse . . . (5) Whether the applicant is delinquent on any outstanding debts or child support payments . . .” (emphasis added). When a state predicates voting eligibility for those convicted of felonies on the full payment of child support, citizenship quite literally carries a price.

In short, state policies that impose arduous child-support obligations during incarceration increase the likelihood that a failed father will exit the prison gate.

Like policies that impose unrealistically high child-support payments, prison practices that hinder incarcerated fathers’ ability to maintain contact with their children undermine a man’s status as father and citizen. As with adjusting child support, fostering the parent-child relationship is both expedient and just. Maintaining family ties improves behavior while men are incarcerated, helps prevent recidivism, and lowers the chances of a prisoner’s children engaging in criminal activity. The capacity to participate in family life should be a right guaranteed the citizen. As long as prison order and security are not compromised and the custodial parent’s ability to care for the children is undiminished, prisoners and their children should be entitled to a sustained relationship.

Yet some policies—those regulating phone, letter, and email communication, and those governing visitation—impose unnecessarily high hurdles to maintaining contact with children while incarcerated.

Letters, phone calls, and visits are the backbone of relationships across prison walls. Snail mail has some obvious advantages. Letters are less expensive than phone calls, and writers can reflect on what they want to say and how to say it. Both child and father can also keep and reread a letter, maintaining a sense of contact beyond the length of a phone conversation. But letters require that both sender and recipient read and write easily, and children may be embarrassed by the stamped advisory on the envelope indicating that the letter has been sent from a correctional facility. Email and other forms of Internet communication are almost universally barred because of monitoring difficulties.

A phone call might seem the simplest and most direct way to stay in touch, but policy in some states stands in the way of this otherwise ordinary form of parent-child contact. Some states limit the number of calls a prisoner can make: a Texas regulation allows offenders who demonstrate good behavior no more than a five-minute phone call every three months. But the major impediment to frequent phone contact is the cost. Many states award an exclusive contract to one service provider, and in exchange for the contract those companies regularly return a substantial part of their profits to the state as commission. Service is often limited to outgoing collect calls. Not surprisingly, rates are exorbitant. In recent years, in one state, the cost of a fifteen minute collect call to another part of the state was $17; in another, the rate for an interstate collect call was $0.89 per minute plus a $3.95 connection fee totaling $17.20 for a fifteen minute call. C. F. Hairston, a University of Illinois professor whose pioneering research on the impact of incarceration and reentry on families has inspired much of the work in the field for a decade, found in 1999 that a thirty minute state-to-state collect call placed from prison on the weekend cost $15; from outside prison, $5; and dialed direct from a residence, $1.50. Such fee structures are patently unfair.

The phone companies contend that the additional security measures required by serving the prison drive up their costs. There are legitimate security concerns involving telephone contact between those in prison and those on the outside: inmates have arranged drug deals, robbery, gang activity, assault, and even murder from behind bars. Unlimited and unmonitored phone access would both increase the risk to corrections personnel and in many cases impede efforts at rehabilitation. Technology, however, has lowered the cost of monitoring calls. Until recently security involved operators listening in on telephone conversations as they occurred. Today the kinds of technological advances that have brought caller-ID, three-way calling, and call-forwarding to the general public allow prison phone systems to automatically monitor and record all calls without operator assistance. Computer interfaces also enable authorities to analyze conversations later.

Regardless of the rationale, the effect of high rates for collect phone calls is devastating for prisoners’ families. Maintaining regular phone contact between parent and child can put severe stress on the finances of the caregiver. Family members may refuse to accept collect calls, or block all such calls. Fathers may not be able to congratulate a child on a birthday, holiday, or significant achievement, much less keep abreast of the mundane but essential events in a child’s life.

High phone costs are not, however, an immutable characteristic of American prisons. Nebraska charges $1 for a fifteen-minute collect local call and $3.75 for a fifteen-minute collect out-of-state call; Washington, D.C., charges a flat rate of $3 for fifteen minutes local or long distance; and West Virginia, New Hampshire, Missouri, New York, North Dakota and Wisconsin also have low rates. States can decline to charge commissions, as New York has recently done, and allow prisoners to place outgoing calls using debit phone cards rather than forcing them to rely exclusively on collect calls.

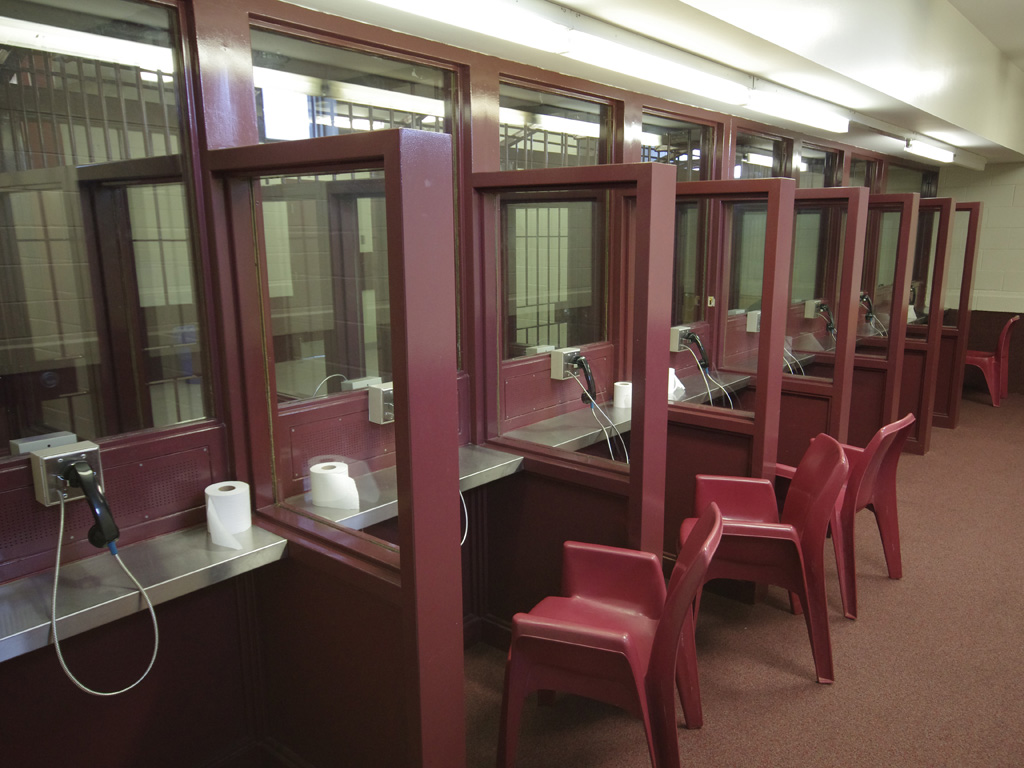

In addition to phone contact, child advocates say that visitation is integral to maintaining, and in some cases improving, a parent-child relationship. The obstacles to visitation between incarcerated parents and their children are, however, truly daunting and exact a high toll in money, time, and dignity. Correctional institutions are often located at a considerable distance from the child’s home; a visit can entail the expense of bus tickets, an overnight stay in a motel, and food on the road and from vending machines in the visitation room. The trip to the prison may also mean the loss of one or two days’ wages. The cost of visiting a parent incarcerated in another state can be prohibitive.

Even for children able and eager to see an incarcerated parent, visitation can be a frightening experience. In her 1999 memoir The Prisoner’s Wife, Asha Bandele describes the procedures for passing through security as “ceremonies of belittlement” for women, and pat-downs and scanning with a wand can be upsetting or humiliating to a child. Most prisons have no separate waiting rooms for children, and visits usually take place in crowded rooms or through Plexiglas or wire barriers. One study of juvenile prisons in Northern California shows that initial excitement often gives way to awkwardness or disappointment for incarcerated fathers and their visiting children because of the lack of opportunity for casual interactions. Eating together is one shared activity they enjoyed, but it is allowed for less than half an hour. Strikingly, in most of the facilities there were no toys or games, making it hard for fathers to interact with their children. Simply improving the visitation area and providing games, toys, or structured activities, as has been done in Sing Sing in New York State, would go a long way to fostering bonds between father and child.

In Overton v. Bazzetta (2003), the Supreme Court unanimously upheld a Michigan regulation that limited visitation in prisons. The regulation bars prisoners who have twice committed drug infractions from receiving family visits, including non-contact visits from behind a reinforced window. The regulation also precludes visits for all inmates by a minor unless the minor is the child, stepchild, or grandchild of the prisoner and accompanied by a guardian or adult member of the prisoner’s immediate family. Children of a prisoner whose parental rights have been terminated are not allowed to visit, regardless of the custodial parent’s views about the desirability of visitation.

The Court said that since a prisoner could write letters or use the phone, neither the regulation denying visitation to a prisoner found guilty of two violations of disciplinary rules due to substance abuse, nor the regulation that a minor child of the prisoner be accompanied by an immediate family member, severed communication between parent and child. The ruling gave insufficient weight to the claims of both prisoners and their families, especially the children, who are most likely to suffer from not seeing their fathers. The Michigan regulation punishes family members just as surely as prisoners.

The goals that the regulations were intended to serve—reduction of the overall number of visitors and reduction of smuggling of contraband—could have been met by more careful screening of adults, by restrictions on the number of visits or the number of visitors allowed each prisoner each month, or by restricted non-contact visits. The ACLU points out that “a decree that one shall never again see one’s family and friends . . . entails the total destruction of the individual’s very personhood.” If a choice must be made concerning who may visit, minor children seeking to visit a parent should receive high priority. The destruction of a relationship is hardly incidental to either father or child, but affects personality, identity, and personhood.

Improved conditions for visitation are not unrealistic. The Osborne Association, a long-established service organization that supports prisoners and their families, has organized both parenting classes and a Children’s Center at Sing Sing. Nell Bernstein describes the Children’s Center in All Alone in the World: Children of the Incarcerated (2005):

Within the Children’s Center—a small, Plexiglas-enclosed enclave off to the side of the larger visiting room—all this [environment frightening to a child] evaporates. Inside the center, fathers can hug and hold their children, read books to them, play computer games with them, or help them weave key chains out of colored string. Security dictates the transparent walls—correctional officers must be able to see in—but their effect is the opposite of the Plexiglas that separates parent and child in a traditional window visit . . . the expanse of the visiting room disappears, creating a sense of shelter and privacy, a glass-enclosed island in an ocean in a bottle.

In addition, some prisons use technology to foster parent-child interaction even without physical visitation. Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Mississippi, New Hampshire, and Oregon have programs that promote literacy for prisoners and their children by allowing parents to create an audio or video recording of themselves reading a book, and both tape and book are then sent to the child. The parent can, in effect, read aloud to the child, a positive and nurturing activity.

Elizabeth Gaynes, Executive Director of the Osborne Association, has argued against “relieving” incarcerated fathers from parental responsibilities. Writing of the incarcerated father of her own children, she said, “I expected him to participate in raising his children, and he did. We entered into a covenant, as important to us as marriage vows, about how we would raise our children.” The value (both symbolic and real) of such a covenant is inestimable. Yet the state, in addition to parents, must commit itself to making parental responsibility to children possible. A three-way covenant would need to ask what obligations the state/correctional facility also bears in maintaining, or at least imposing no further harm upon, the paternal bond.

Families are crucial to civil society. They foster personal wellbeing and help people develop the moral capacities necessary for self-governance and public deliberation. Throughout U.S. history, the ability to form and maintain a family has been a mark of dignity, what NYU Law Professor Peggy Cooper Davis has called “a badge and incident of democratic freedom.” One of the marks of full membership in civil society is recognition of and respect for one’s status as a family member.

Fatherhood is not only an important dimension of an individual’s sense of identity, but is also related to his social and civic status in complex ways. Recognition of and respect for family relationships is due all U.S. citizens and care must be taken that state action not weaken family ties. At the same time, “good parenting” must not be a prerequisite for exercising the vote, just as voting is not a prerequisite for exercising the right to custody of or visitation with one’s child. It is of both practical and theoretical interest that we recognize the importance of family to incarcerated men. According to a John Jay College of Criminal Justice study, by disrupting family connections, prisons in fact contribute to the increased criminality among youth. Researchers at Harvard University and the University of Maryland have also shown that marriage reduces incidence of crime over the course of one’s life.

One of the impediments to maintaining incarcerated fathers’ relationships with their children has been the tendency—in law, political culture, and political theory—to depict individuals as isolated persons, rather than as having identities formed through relationships. But family relationships are not “add-ons” or incidental to a person’s identity; they are in part constitutive of that identity. As a result, the state must respect the right of people to form relationships even when they are incarcerated, as the Supreme Court did when it upheld a prisoner’s right to marry in Turner v. Safley (1987). But it cannot stop there. It should also avoid unnecessary disruption of relationships.

The federal Department of Health and Human Services’ “responsible fatherhood” initiatives fund a growing number of parenting programs in prisons. These programs are helpful when they encourage incarcerated fathers to consider how they can support the child-rearing efforts of the child’s mother or guardian, and not when they draw on traditional tropes of masculinity and male authority for legitimacy. Family reunion programs, which combine conjugal and family visitation, exist in six of the fifty states. The surge of interest in reentry has fostered a renewed focus on job/training programs in prison that could have great import for fathers in prison. These are valuable initiatives, but they are still few in number.

Whatever the reasons for limited support of prison programs for fathers, prison security is not one of them. The wide variation in state systems’ approaches to child support or prison visitation/phone rules implies that “penological interests” (the typical judicial invocation in striking down prisoner-rights claims) is not the driving imperative preventing more expansive fatherhood policies.

The stakes in these more expansive policies are large and extend to basic issues of justice. Suspending, or at least modifying, child-support obligations for fathers who cannot meet assigned awards on state-set wages earned in prison, abrogating any child-support “poll tax” on voting eligibility, and facilitating communication between fathers and their children concern both the prisoners who seek to move beyond a sense of failed fatherhood and the children who bear the collateral damage of measures that distance them from their fathers. Recognizing that intimate and caring relationships are essential to human well-being, the Supreme Court has determined that prisoners must have the right to marry. Law and public policy need to extend these relational interests to the maintenance of ties between parents and children.

When remediable conditions of incarceration make it unnecessarily difficult or impossible for an inmate and his family to maintain ties, this is not simply a private wrong and a personal misfortune. It is also an unjustifiable diminution of the inmate’s civic status. Contemporary citizenship entails the right of both adults and children to form and maintain relationships that are central to the development and expression of autonomy and to the dignity and mutual respect that citizens owe one another. The recognition and encouragement of fatherhood behind bars is a vital step in maintaining and fostering the interrelated—indeed, inseparable—commitments of both intimate and civic life.