In introducing their proposal for a wealth tax, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman appeal to the arguments of James Madison. In a republic, he contends, the laws must operate to “reduce extreme wealth towards a state of mediocrity, and raise indigence towards a state of comfort.” Building on this insight, Saez and Zucman set out a compelling case for a progressive wealth tax.

But a wealth tax aims at just the first of the two goals that James Madison sets out: reducing “extreme wealth”—if not to a “mediocrity,” then at least to levels more compatible with social and political equality. What about the other half of his point, the imperative to raise “indigence” to a state of modest affluence?

We should care about establishing a floor on wealth as well as a ceiling for at least three reasons.

The first echoes a chief concern behind the wealth tax proposal: political equality. Wealth poverty—not just low income, but low wealth—can limit political influence in numerous ways. It makes it harder to donate to campaigns or provide financial support for other forms of political expression. Those without wealth are likely to be more reliant on employment for income. As the philosopher Elizabeth Anderson points out in her book Private Government (2017), the nature of many employment contracts gives employers considerable power to regulate employees’ political activities. A lack of wealth limits the ability of the worker to walk away in the face of this potential domination.

Second, wealth poverty obstructs fair equality of opportunity. In a just society, individuals should have roughly similar and extensive opportunities for education and economic success irrespective of social background. A lack of wealth inhibits opportunity. It makes it harder to fund education and training and to start a new business. Investors and creditors often require collateral, and collateral is exactly what the wealth poor don’t have.

Third, wealth poverty reduces freedom and security. Those who hold wealth of their own have a greater degree of material independence from others. This enhances their ability to exit a wide range of social relationships, and thereby increases their power within them. Wealthier people are freer in the sense of being able to walk away from relationships in which others try hold sway over them. Wealth poverty also makes it harder to cope with unanticipated expenses and loss of earnings, and so increases the stress of making ends meet.

One might find all of this idle philosophy if the United States did not have a wealth poverty problem, but it certainly does. “Many Americans do not have a sufficient financial buffer to offset the loss of a job, a medical emergency or relationship break up and remain in the middle class,” notes a recent study by Darrick Hamilton and colleagues. The problem is particularly acute for black families: “The typical black family essentially has no economic cushion. Most black families have no more than $25 in non-retirement liquid wealth.” Among white families, those in the bottom income quintile have much more net worth than comparable black families but still hold less than $55 in liquid wealth available to handle immediate emergencies.

A number of proposals might help to raise wealth where there is too little of it. Perhaps the simplest is the proposal for universal capital grants or basic capital (not to be confused with basic income). Under this proposal, every U.S. citizen would receive a lump-sum capital grant early in their adult lives. This idea was worked up some years ago by legal scholars Bruce Ackerman and Anne Alstott in their book The Stakeholder Society (1999). A variant is the Child Trust Fund, enacted for a while in the United Kingdom, under which all children receive a modest endowment at birth, which is invested in a capital account to accumulate as they grow up, becoming accessible on reaching adulthood. More recently, in the United States, the economist William A. Darity, Jr., and colleagues at the Samuel DuBois Cook Center for Social Equity at Duke University have developed a similar “Baby Bond” proposal, which has informed Senator Cory Booker’s American Opportunity Accounts Act.

Another possibility is the Individual Development Account (IDA) elaborated in the research of Michael Sherraden and colleagues. Under this proposal, households with little wealth are enabled to set up special savings accounts in which their own savings are matched by third-party contributions. Some of the effects of a universal wealth endowment can also be achieved by building up a collective investment fund and using some of the return on the fund to finance a universal social dividend payment. The state of Alaska already has a version of this in the form of the Alaska Permanent Fund, established by an amendment to the state constitution in 1976 under Republican governor Jay Hammond. Why not extend this idea, as Angela Cummine suggests in Citizens’ Wealth (2016), and establish a federal sovereign wealth fund?

As for the question of where the funds to enact one or more of these proposals might come from, one obvious option suggests itself: why not use the revenue raised from a wealth tax? Why not make an explicit policy link between action on the wealth ceiling and the wealth floor?

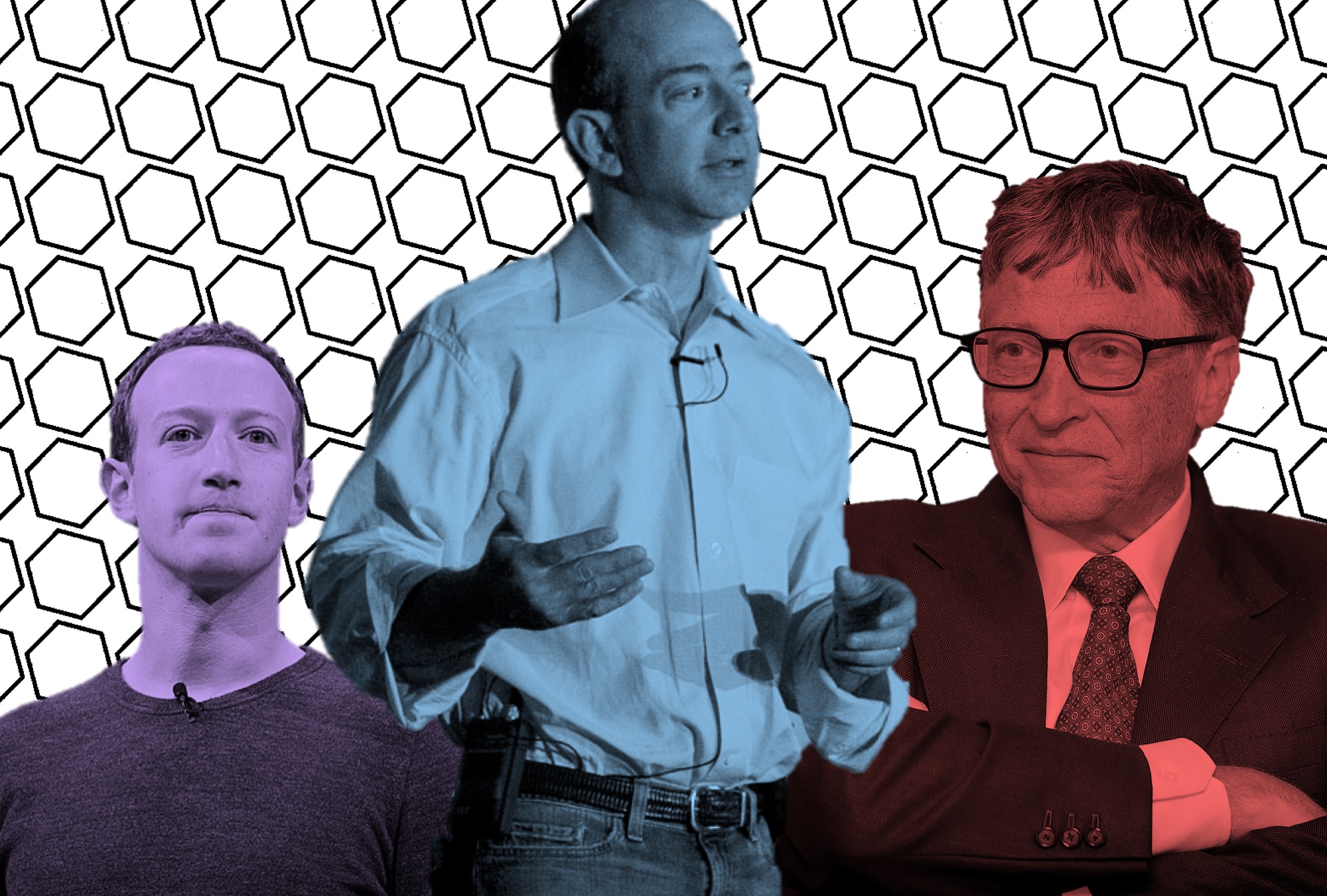

Saez and Zucman have estimated that a tax of 2 percent on net worth above $50 million combined with an additional 1 percent on net worth above $1 billion will raise in the region of $210 billion a year. As part of a comprehensive economic package, this can be used to help fund the phase in of a universal capital scheme, or IDAs, or to help set up a nation-wide version of the Alaska Permanent Fund to provide every U.S. citizen in time with a modest social dividend.

There is a strong moral intuition here. If the extreme wealth of the superrich is undeserved—as it is—and a danger to democracy—as it is—we should in principle return it directly to the wider society and enhance democracy in the process. There is also, perhaps, a related political benefit. Linking a wealth tax to policies that create a wealth floor is a way of making even clearer that this is a policy for the common good: that it is not a punitive levelling-down but rather a compelling, necessary step in spreading opportunity and freedom to all.