On December 30, 1994, an opponent of abortion opened fire at two Brookline clinics, killing two people and injuring five others. He then went south to spray twenty rounds of ammunition into a clinic in Norfolk, Virginia. That episode was only the most extreme in a series of recent attacks on abortion providers. In the two-year period ending in December 1994, five people were murdered and at least nine wounded in similar assaults.

Between 1992 and 1993, five people were murdered during assaults on abortion clinics.

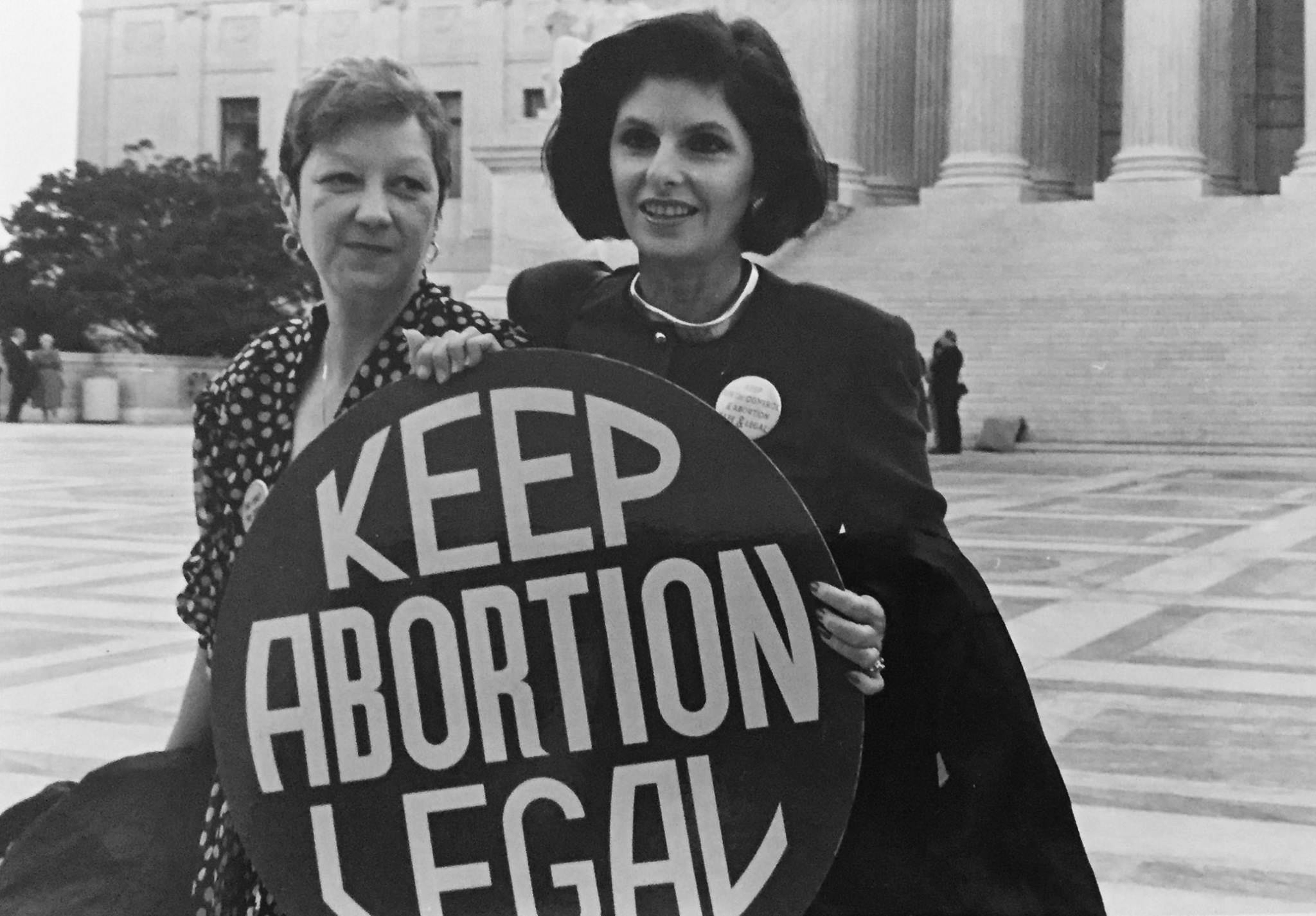

With the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey,1 the constitutional right to abortion seems to have become secure, at least for the time being. Concurrently, however, exercise of the right has been under increasing threat. Clinic officials report bombings, arson, and vandalism. Their insurance costs have risen, and they must pay heavily for security guards. Doctors who perform abortions are subjected to threats of violence, and they and their families are harassed; a new tactic, the malpractice suit, increases their costs.2 The number of doctors who are willing to perform abortions is therefore decreasing, and women in rural areas have to travel long distances to obtain abortions. Indeed, the pool of doctors who are able to perform abortions is likely to shrink too, because, under anti-abortion pressure, many hospitals and medical schools no longer teach abortion procedures. Clinic entries are blockaded, and even after the police are able to clear a path to the door, the women who walk it are subjected to shouted threats and insults: they are made to walk it in fear and humiliation.

Some of us had hoped that with time, opposition to abortion would become less violent, less strident, at a minimum, more open to rational debate. That has not happened. Instead, anti-abortion pressure continues to be a powerful force in politics, perhaps an increasingly powerful force. The Christian Coalition has threatened to withhold support from candidates for national office who do not oppose abortion; and it is the primary source of the many new anti-abortion initiatives now before Congress. The Republican platform has, for years, called for a constitutional amendment to ban most abortions; while Senators Robert Dole and Phil Gramm have recently said that they believe there are not enough votes in Congress to pass a constitutional amendment at this time, each has said that he would, if elected President, use the executive power to limit access to abortion.

And now we have in hand the new Papal encyclical, Evangelium Vitae, in which John Paul II argues, vigorously, that abortion is “murder,” and condemns laws permitting abortion as “intrinsically unjust,” “lacking in authentic juridical validity,” and not “morally binding.”3 He therefore calls on everyone to oppose both abortion and the laws that permit it.

The recent escalation of threats to exercise of the right to abortion, the continuing political power of abortion opponents, and the appearance of the new encyclical, call for a response. Those who value the abortion right should not let these things simply wash over them, as if all that matters is that the legal right was won, and occupation of the moral high ground can be left to whoever wants it. That is dangerous, both to the right itself and to the self-respect of those who value it.

Let us begin by reminding ourselves of what is at stake for women in the abortion controversy.

Anti-abortion pressure continues to be a powerful force in politics, perhaps an increasingly powerful force.

Some women want abortions. Why? They have a variety of reasons. The woman who is pregnant due to rape may feel devastated by the prospect of carrying and giving birth to the child of the man who violated her. The woman whose health is already at risk may not want to undergo the increased risk that carrying the fetus to term would impose on her. The woman who has already had several children, and has now been deserted by the man she lived with, may believe herself unable to supply a decent life for yet another child. A woman may discover that the child she will deliver will be horribly deformed. A woman who is preparing to embark on a career that requires hard work and single-mindedness may prefer to wait until she is in a position to give a child the attention a child needs.

Opponents of abortion seem to think that women who choose to have abortions typically do so thoughtlessly. Hence the common idea that if abortion is to be available at all, it should be available only after a 24-hour waiting period, during which time the woman can be allowed, indeed invited, to contemplate the seriousness of the step she has decided to take. Why this forced contemplation? Does any woman decide on an abortion thoughtlessly? Surely not. It should not need repeating—over and over again—that women who decide on abortion typically do so for weighty reasons, and that their decisions have already been preceded by serious thought.

Other women do not want abortions for themselves, but want abortions to be available to others. I have two things in mind here. First, there are the children who become pregnant. The literature on abortion typically refers to pregnant women, but 13 year-old girls are not women, they are children. Many women regard it as an outrageous idea that a child, pregnant due to rape or seduction, is morally required to carry the fetus to term. Second, and more generally, many women rightly believe that constraining access to abortion impedes the achievement of political, social, and economic equality for women. If women are denied rights over their own bodies, they are denied rights to equal participation in the work of the world; if they are not permitted to make, for themselves, such deeply important decisions as whether to bear a child, they are not permitted to occupy the status of autonomous adult, morally equal to men.

So this is an issue of great importance to women. Denial of the abortion right severely constrains their liberty, and among the consequences of that constraint are impediments to their achievement of equality. This fact is itself important, and I will return to it later.

But if abortion were murder, all that would amount to little. Suppose that a fetus is a product of rape, or that allowing it to develop would constitute a threat to the woman’s health or make it impossible for her to supply a decent life to other already existing children, or that it is deformed, or that allowing it to develop would interfere with plans that are central to her life. If killing the fetus were murder, the woman would have to carry it to term, despite the burden on her of doing so. Morality, after all, does not permit us to commit murder in the name of avoiding such burdens. You certainly may not murder your five year-old child just because it is a product of rape, or because its demands on your attention get in the way of your career.

Why, then, is it to be thought that abortion is murder? A familiar argument starts from the premise that a human being’s life begins at conception. (We are invited to accept that premise on the ground that the conceptus—a fertilized human egg—contains a biological code that will govern its entire future physical development, and therefore is already a human being.) Moreover, human beings have a right to life. A human being can forfeit that right by, for example, unjustly aggressing against another. But, the argument continues, the fetus, at all stages of its development, is innocent of any aggression. (As the encyclical says: “No one more absolutely innocent could be imagined. In no way could this human being ever be considered an aggressor, much less an unjust aggressor.”) And so the argument concludes: abortion at any stage, from conception on, is a violation of the right to life, and thus is murder.

Why, then, is it to be thought that abortion is murder?

As I said, this argument is familiar. According to Ronald Dworkin, however, opponents of abortion do not really mean it. In his interesting recent book on abortion and euthanasia,4 Dworkin argues that opponents of abortion do not really believe that the fetus has a right to life, but only something weaker, namely that “it is intrinsically a bad thing” when a fetus is deliberately destroyed (LD, p. 13). He gives two reasons for this surprising conclusion, and I will turn to them shortly. But let us first see that this idea is weaker.

Dworkin says that you do not have to think that a thing has a right to life in order to think it intrinsically bad to destroy it: he draws attention to the fact that there are lots of things we regard as intrinsically bad to destroy, but which we do not take to have rights to life. Great works of art, for example. So similarly, he says, you might think that destroying a fetus is intrinsically bad without thinking it has a right to life.

Now suppose it would be intrinsically bad to destroy a thing. Still, destroying it might be permissible, for it might be intrinsically worse not to destroy it. Consider a great painting, for example. Suppose that we have to choose: we must destroy the painting or a child will die. It would be intrinsically bad to destroy the painting, but intrinsically worse that a child die.

In short, where there is badness there is betterness and worseness. And if you think merely that killing a fetus in an abortion is bad, but not a violation of a right, then it is open to you to make exceptions, for it is open to you to think that something even worse will come about if it is not killed.

Dworkin’s proposal, then, is this: opponents of abortion say that the fetus has a right to life, and—given its innocence—that abortion is therefore murder, but what they really believe is only that killing the fetus is intrinsically bad.

He gives two reasons for attributing this view to them. First, many opponents of abortion do make exceptions. For example, they are prepared to allow abortion where the pregnancy is due to rape or incest, or where the woman’s life is at risk if the pregnancy continues. But if abortion was a violation of the right to life, and therefore was murder, no exceptions could be made for such cases; thus if you think abortion is murder, you cannot consistently also think that such cases are exceptions. So Dworkin’s first reason for attributing to them the view that abortion does not violate a right but is only something intrinsically bad is that if we do so we can suppose that their moral beliefs are consistent.

Second, Dworkin says that it is “very hard to make sense of the idea” (LD, p. 15) that a fetus has rights from the moment of conception. Having rights seems to presuppose having interests, which in turn seems to presuppose having wants, hopes, fears, likes and dislikes. But an early fetus lacks the physical constitution required for such psychological states. How can we so much as understand the proposal that a fertilized human egg has hopes, for example? And if a man says what lacks sense, then we have at least some reason for thinking that he does not really believe what he says he believes.

For those two reasons, then, Dworkin attributes to opponents of abortion the view that abortion is not really the violation of a right but is merely intrinsically bad. He then goes on to make a case—an impressive case—for saying that a person who believes that abortion is merely intrinsically bad should accept the propriety of a legal regime with a constitutionally guaranteed abortion right.

How are we to make sense of the idea that an early fetus, much less a fertilized human egg, has rights?

Dworkin’s interpretation of the views of abortion opponents is not compelling, however. Consider John Paul II’s encyclical again. It contains exactly the familiar argument I laid out above: it explicitly declares that abortion at any stage, from conception on, is “the deliberate killing of an innocent human being” and thus is a violation of “the right to life of an actual human person” and thus is “murder.” Can we plausibly follow Dworkin and attribute to the Pope the view that abortion is not really a violation of the right to life, but is merely intrinsically bad? I hardly think so.5

And not simply because the Pope’s words are so clear. For consider again Dworkin’s first reason for attributing this view to opponents of abortion, namely the fact that they make exceptions for abortions in some circumstances (rape or incest or a risk to the woman’s life), and that their moral views would therefore be inconsistent if we attributed the stronger view to them. No doubt some do make exceptions; the encyclical, however, does not. According to the encyclical: “The killing of innocent human creatures, even if carried out to help others, constitutes an absolutely unacceptable act.”

What of Dworkin’s second reason? How are we to make sense of the idea that an early fetus, much less a fertilized human egg, has rights?

Well, why can’t we make sense of it? Here is the answer I pointed to earlier: having rights seems to presuppose having interests, which in turn seems to presuppose having wants, hopes, fears, likes and dislikes. But an early fetus, a fertilized egg, is plainly not the locus of such psychological states.

To be sure, if a fertilized egg is allowed to develop normally the resulting child will have wants, hopes, and fears, and thus will have interests, and it will then have rights. But this does not show that fertilized eggs have rights. Things can lack rights at one time and acquire them later. If children are allowed to develop normally they will have a right to vote; that does not show that they now have a right to vote. To show that a fertilized human egg now has rights one needs to produce some fact about its present, not its future.

On the other hand, it is not obvious why we should accept even the first part of the answer I pointed to. Why should we agree that having rights presupposes having interests? There is a difficulty here that we need to stop over.

What, after all, is it to have a right? Very roughly, for a person, say Alfred, to have a right that we do something is for the following to be the case: the fact that we would improve the world by not doing it does not itself justify our not doing it. Suppose, for example, that Alfred admires our antique teapot, and that we have promised to give it to him, thereby giving him a right that we will. Suppose it then turns out that Bert and Carol also admire our teapot. Perhaps the world would be better if we gave it to Bert and Carol as joint owners. (Two of the three people pleased rather than only one.) That fact does not itself justify our giving it to them rather than to him—since by hypothesis, he has a right that we give it to him.

Again, for Alfred to have a right that we refrain from doing something is for the following to be the case: the fact that we would improve the world by doing it does not itself justify our doing it. Suppose we can save Bert’s and Carol’s lives by killing Alfred. Perhaps the world would be better if we killed Alfred. (Two of the three people alive rather than only one.) That fact does not itself justify our killing Alfred—on the assumption that Alfred has a right to life, and thus a right that we not kill him.6

In short, having a right is having a certain morally protected status. In an earlier work, Dworkin suggested that we should think of rights as “trumps”: the fact that by our act we can bring about more that is good than would otherwise come about is trumped by the fact (if it is a fact) that someone has a right that we not so act. In particular, what it is merely bad to destroy we may destroy just in the name of bringing about something better; what has a right not to be destroyed we may not destroy just in the name of bringing about something better.

So for a fetus to have a right to life is for it to have that morally protected status. The familiar argument that I set out above declares that it does. What reason is there to think it doesn’t? Dworkin says that it is very hard to make sense of the idea that an early fetus, a fertilized human egg, has a right to life. It seems to me, by contrast, that the idea makes perfectly good sense. Perhaps the idea that a fetus does have that morally protected status is false. All the same, the idea that a fetus does have it cannot be bypassed as nonsense. We have to take the idea seriously.

The idea that a fetus has rights cannot be bypassed as nonsense. We have to take the idea seriously.

I am in fact going to discuss only fertilized eggs, for two connected reasons. In the first place, the familiar argument I set out does not say merely that a late fetus has a right to life; it says that a fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception. If fertilized eggs have no right to life, then anyway that argument against abortion is blocked. But second, if that argument is blocked, then what is the opponent of abortion to replace it with? There is room for him to argue that as the fetus develops, it acquires features in virtue of which it then has a right to life, perhaps a certain level of neural development, perhaps viability, perhaps other features. That is all very well, but his making this choice commits him to thinking that some abortions are morally permissible, namely those that precede the time at which the fetus acquires the relevant features; and—depending, of course, on his choice of features—perhaps that most actual abortions are morally permissible. (Fully half the abortions in the United States currently take place within the first eight weeks of pregnancy, some four months before viability.7 At eight weeks, the fetus is about one-and-a-half inches long, and has only recently lost its tail.) Moreover, we can then enter discussion with him about why the features he fixes on should be thought to be the ones that make the moral difference. It is entirely possible that the outcome of such a discussion would be his taking a moral stance on abortion that is, if not the same as, then close to the stance on abortion enshrined in current law.

In sum, what needs attention is not the question “What is to be said to a person who asserts only that more or less late abortion is the killing of what has a right to life?” but rather the question “What is to be said to a person who asserts that all abortion is the killing of what has a right to life?” The vehemence of the opposition to abortion surely issues, not from the idea that a middle-to-late abortion is murder, but rather from the idea that all of it is. In any case, the new papal encyclical brings home to us that the stronger idea calls for a response.

So let us ask: what reason is there to deny that fertilized eggs have a right to life?

If having rights really does presuppose having interests, and that in turn presupposes having wants, hopes, fears, likes and dislikes, then—since fertilized eggs are not the locus of such psychological states—it follows that fertilized eggs have no rights at all, and a fortiori that they do not have a right to life. But why should we agree that having rights presupposes having interests?

The idea that having rights presupposes having interests seems very plausible, for reasons that emerge as follows.

Paintings, for example, have no interests. It is possible to do to a painting what is good for it: perhaps dusting it regularly is good for it. It is possible to do to a painting what is bad for it: perhaps leaving it in strong sunlight is bad for it. But dusting it regularly does not advance its interests, and leaving it in strong sunlight does not impede its interests. Doing these things may advance or impede its owner’s interests, but it has none.

Now wronging a creature is impeding its interests unfairly. Since paintings have no interests, there is no such thing as impeding their interests unfairly, and therefore no such thing as wronging them. If we put Alfred’s painting in strong sunlight, we may be impeding his interests unfairly and thereby wronging him; we are not wronging the painting.

Suppose, now, that we can improve the world by doing what is bad for a painting. We do not wrong it in so acting. Suppose also that we wrong no one else in so acting. Then our doing what is bad for the painting wrongs no one. Since, by hypothesis, our doing what is bad for the painting would improve the world, it is permissible for us to proceed.

It follows that paintings lack the morally protected status I described, and thus that they lack rights.

I think that these considerations do make the idea that having rights presupposes having interests seem very plausible. But would it be flatly unreasonable to deny that idea? I think not. Here is the difficulty. We may grant that if a thing lacks interests, then it is not possible to impede its interests unfairly, and therefore that it is not possible to wrong it. But if having rights is having the kind of protected moral status that I described, then we stand in need of an explanation of why it should be thought that a thing has that special status only if it is possible to wrong it. No doubt you can’t wrong a painting. But how do we get from there to the conclusion that paintings lack the protected moral status? There is a gap here. It seems entirely reasonable to cross it, but we lack a compelling rationale for doing so.

There is nothing contrary to reason in refusing to lend any credence to the idea that fertilized eggs have a right to life.

I know of no other reason for denying that fertilized eggs have a right to life than the one that rests on the idea that having rights presupposes having interests. So I know of no conclusive reason for denying that fertilized eggs have a right to life—thus I know of no conclusive refutation of the encyclical’s assertion that they do have a right to life.

There is another side to this coin, however. While I know of no conclusive reason for denying that fertilized eggs have a right to life, I also know of no conclusive reason for asserting that they do have a right to life. Here I do take issue with the encyclical. For according to the encyclical, the doctrine that the fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception “is based upon the natural law” as well as “upon the written Word of God.” It says that the doctrine “is written in every human heart, knowable by reason itself…” (my italics). But the claim that this doctrine is known by reason to be true simply will not do. There is nothing unreasonable or irrational in believing that the doctrine is false.

More strongly, there is nothing unreasonable in believing that the doctrine is entirely without support. There is nothing contrary to reason in refusing to lend any credence at all to the idea that fertilized eggs have a right to life.

It is important to stress this stronger claim. The encyclical says: “what is at stake is so important that, from the standpoint of moral obligation, the mere probability that a human person is involved would suffice to justify an absolutely clear prohibition of any intervention aimed at killing a human embryo.” The stronger claim says that reason does not compel us to believe it more probable that an embryo is a human person than that any piece of human tissue is. If allowed to develop normally, an embryo will develop into a human person, whereas a cell in your thumb will not; it is not contrary to reason to think that that lends no weight at all to the idea that the embryo is a human person now.8

It pays to remember also that people who think there is no reason at all to believe that fertilized eggs have a right to life may well share a considerable amount of the morality that is accepted by people who believe that fertilized eggs do have a right to life. In his well-known speech at Notre Dame on the place of his Catholicism in his life as an elected official, Mario Cuomo said:

Those who don’t [agree]—those who endorse legalized abortions—aren’t a ruthless, callous alliance of anti-Christians determined to overthrow our moral standards. In many cases, the proponents of legal abortion are the very people who have worked with Catholics to realize the goals of social justice set out in papal encyclicals: the American Lutheran Church, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Presbyterian Church in the United States, B’nai B’rith Women, the Women of the Episcopal Church. These are just a few of the religious organizations that don’t share the [Catholic] church’s position on abortion.9

Thus there are many people who reject Catholic doctrine on abortion, people who not only cannot be convicted of irrationality, but who act in other areas of life in a manner a Catholic respects. What this brings home to us is that a person who rejects this part of Catholic morality cannot be viewed by someone who accepts Catholic moral doctrine as thereby revealing a quite general moral disorder or deficiency. The encyclical, unfortunately, denies this. It says: “The acceptance of abortion in the popular mind, in behavior and even in law itself, is a telling sign of an extremely dangerous crisis of the moral sense, which is becoming more and more incapable of distinguishing between good and evil, even when the fundamental right to life is at stake.” This does not say, but it certainly suggests, that those who reject Catholic doctrine on abortion are incapable of distinguishing between good and evil. So interpreted, it is a thoroughly groundless assault on their moral integrity.

If abortion rights are denied, then a constraint is imposed on women’s freedom to act in a way that is of great importance to them.

These facts have consequences for the debate about the legality of abortion. As I reminded you at the outset, a great deal turns for women on whether abortion is or is not available. If abortion rights are denied, then a constraint is imposed on women’s freedom to act in a way that is of great importance to them, both for its own sake and for the sake of their achievement of equality; and if the constraint is imposed on the ground that the fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception, then it is imposed on a ground that neither reason nor the rest of morality requires women to accept, or even to give any weight at all. A legal regime that prides itself on respect for liberty cannot in consistency constrain a deeply valued liberty on such a ground. We should be clear why. When a deeply valued liberty is constrained on a ground that the constrained are not in the least unreasonable in rejecting outright, then what is done to them cannot be justified tothem, and imposing the constraint on them is therefore nothing but an exercise of force.

The point I make here is not just that anyone who wants to impose a severe constraint on liberty has the burden of saying why it is permissible to do so. That hardly needs saying. The point here is, more strongly, that discharging the burden requires more than merely supplying a reason for the constraint: the reason for the constraint has to be one that the constrained are unreasonable in rejecting. In particular, it is not acceptable to constrain access to abortion and supply by way of reason merely “The fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception.” Compare the French absolutist Bossuet, who declared “I have the right to persecute you because I am right and you are wrong.”10 Under a decent legal regime, people cannot persecute others on the sheer ground that (so they say) they are right and the persecuted are wrong. So similarly for severe constraints on liberty under a legal regime in which liberty is a fundamental value.

This fact breaks what some people have said is a stand-off in the abortion controversy. One side says that the fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception, the other side denies this. Neither side is able to prove its case. The people I refer to ask: why should the deniers win? Why break the symmetry by letting the deniers win instead of the supporters? The answer is that the situation is not symmetrical. What is in question here is not which of two values we should promote, the deniers’ or the supporters’. What the supporters want is a license to impose force; what the deniers want is a license to be free of it. It is the former that needs the justification.

I hope it is clear that my objection to constraining access to abortion on the ground that the fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception is not that this is Catholic, and hence religious, doctrine. My objection is not that constraining the liberty on the ground of this doctrine violates the principle of separation of church and state. If the legislature constrains the liberty on the ground of this doctrine, and declares that it is entitled to do so because God says the doctrine is true, then the legislature does violate the principle of separation of church and state. But no sensible contemporary opponent of abortion invites the legislature to do this. The opponent of abortion instead invites the legislature to constrain the liberty on the ground of this doctrine, and to declare that it is entitled to do so because the doctrine is true. My objection remains.

In sum, my case here against restrictive regulation of abortion rests on three ideas. First, restrictive regulation severely constrains women’s liberty. Second, severe constraints on liberty may not be imposed in the name of considerations that the constrained are not unreasonable in rejecting. And third, the many women who reject the claim that the fetus has a right to life from the moment of conception are not unreasonable in doing so. All three ideas seem to me very plausible.

There is of course room for those who accept Catholic doctrine on abortion to declare it in the public forum: the public forum is and must be open to all. But two points are worth stress.

In the first place, those who accept the doctrine ought not say that reason requires us to accept it, for that assertion is false. The public forum is as open to the false as to the true, but participants in it ought to take seriously whether what they say is true. There is already far too much falsehood in the anti-abortion movement. A recent newspaper photograph showed an anti-abortion protester holding a placard that said “Abortion kills;” that much is true. But under those words was a photograph of a baby. The baby looked to me about a year and a half old—counting in the ordinary way, from birth, not conception. The message communicated by that placard was that abortion kills fully developed babies, and that is false, indeed, fraudulent. Exaggeration for a political purpose is one thing, fraud quite another.

What fuels the rage of opponents of abortion is not merely that it is now permitted, but that it was permitted by judicial action.

But falsehood is by no means the worst that comes of pronouncements that abortion is murder. Say that often and loudly enough, and some weak-minded soul is sure to start shooting to put a stop to it—as of course has happened, most recently in Brookline. That is the second point to stress about the public forum: what is said there has consequences. Exaggeration for a political purpose is one thing, incitement to do harm quite another.11

One final point, about political action. Some liberals who accept that there ought to be an abortion right are nevertheless critical of the Court’s role in securing that right. They believe that if the democratic process had been left to itself—the issue of abortion left for settlement by legislatures, whether federal or state—the outcome for abortion rights would have been much as it is now, but without the violence. On that view, what fuels the rage of opponents of abortion is not merely that abortion is now permitted, but that it was permitted by judicial action and not left for decision by the majoritarian branch. A thoroughly convincing recent empirical study of the development of views on abortion at and since the time of Roe v. Wade suggests that this hypothesis about access to abortion simply is not true: it concludes that there would have been far less access to abortion than there is now had the issue been left to legislatures.12

And I would add that if I was correct in saying that there is nothing unreasonable in believing that at least early abortion violates no rights, and therefore that the deeply valued liberty to obtain an abortion cannot be constrained on the ground that it does violate rights, then there can be no principled objection to the settlement of the issue by the judicial rather than the legislative branch. Vindicating our fundamental liberties is, after all, exactly what courts are supposed to do.13

ENDNOTES

- 112 S. Ct. 2791 (1992)

- For a description of this new tactic, see The New York Times, April 9, 1995.

- Pope John Paul II, The Gospel of Life [Evangelium Vitae] (New York: Random House, 1995). Unless otherwise identified, all quotations in what follows are from that document.

- Ronald Dworkin, Life’s Dominion (New York: Vintage Books, 1994); I refer to this book henceforth as LD.

- A number of LD’s reviewers have drawn attention to the implausibility of Dworkin’s idea that opponents of abortion mean only what Dworkin says they mean. (See, for example, Stephen L. Carter, “Strife’s Dominion”, The New Yorker, August 9, 1993.) Perhaps some do. Perhaps many do. But many do not.

- My accounts of what it is for Alfred to have the two rights I mentioned are deliberately weak. Thus I did not say that for Alfred to have a right that we give him our teapot is for it to be the case that, come what may, we must give him our teapot, and I did not say that for Alfred to have a right that we not kill him, is for it to be the case that, come what may, we must not kill him. That is because there are circumstances in which it is permissible to infringe a right. For example, rights may conflict, in which case we must, and therefore may, infringe at least one. There are other possibilities too. My own further discussion of the possibilities appears in The Realm of Rights (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990). The fact that there are circumstances in which it is permissible to infringe a right is relied on by those who argue that it is sometimes permissible to kill a fetus even if it does have a right to life. Not, of course, just in the name of improving the world; rather in the name of relieving the mother of an imposition on her that she is under no duty to accede to. An extended recent discussion of these ideas may be found in Frances M. Kamm’s review of LD: “Abortion and the Value of Life,” Columbia Law Review 95 (1995). (Those who take this view think that while abortion may be an infringement of the right to life, it is not thereby marked as murder.) But I will not focus in what follows on the question what one may do given we assume that the fetus has a right to life. I think the time is overdue to focus on the question what weight in constitutional argument may be rested on the assertion that the fetus does have a right to life.

- See Laurence H. Tribe, Abortion: The Clash of Absolutes (New York: Norton, 1990), p. 215. Such an opponent of abortion should welcome the release and distribution of the French drug RU-486, which is effective as an abortifacient when used within seven weeks of the last menstrual period, since its use would shrink even further the number of abortions he takes himself to have ground for thinking morally impermissible. (RU-486 is a post-implantation abortifacient. Tribe reports that high doses of some widely available birth control pills can be used – and are currently used in cases of rape – as pre-implantation abortifacients: Ovral is effective when used within three days after conception. See Tribe, p. 219. No doubt other very early abortifacients will be developed in future.)

- I said earlier that women who decide on abortion typically do so for weighty reasons. If very early (pre-implantation) abortifacients become widely available – see footnote 7 above – many women will regard the question whether to prefer their use to the use of birth control pills as turning entirely on which choice is likely to have fewer unwanted side-effects; and there is nothing contrary to reason in thinking that that is the only relevant consideration.

- Mario Cuomo, “Religious Belief and Public Morality: A Catholic Governor’s Perspective,” published in his More Than Words (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993), p. 42.

- This splendid remark is quoted by Susan Mendus, Toleration and the Limits of Liberalism (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1989), p. 7. I am grateful to Joshua Cohen for the reference.

- Planned Parenthood responded to the Brookline killings in a newspaper ad with the headline “Words Kill,” blaming pro-life rhetoric for the episode. Several days later, Mary Ann Glendon responded by blaming pro-choice rhetoric: the “language of dehumanization” that is displayed in pro-choice use of “deceptive phrases [for the fetus] like ‘clump of tissue’ and ‘product of conception’.” After all, she asked, “how can the pro-choice movement’s rhetoric fail to promote a coarsening of spirit, a deadening of conscience and a disregard for the humanity of one’s opponents…?” Her explanatory leap is breathtaking. See Mary Ann Glendon’s op-ed, “When Words Cheapen Life,” The New York Times, January 10, 1995.

- See Archon Fung, “Making Rights Real: Roe’s Impact on Abortion Access,” Politics and Society 21, no.4 (December 1993). See also Tribe, Clash, and David J. Garrow, Liberty and Sexuality (New York: Macmillan, 1994).

- I am greatly indebted to Joshua Cohen for criticism, suggestions, and advice: I have leaned on him throughout. An early version was presented as the Keynote Address at the 1995 New England Undergraduate Philosophy Conference at Tufts University.