Can the world meet the challenge of climate change? After more than three decades of global negotiations, the prognosis looks bleak. The most ambitious diplomatic efforts have focused on a series of virtually global agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and the Paris Agreement of 2015. With so many diverse interests across so many countries, it has been hard to get global agreement simply on the need for action; meaningful consensus has been even more elusive. Profound uncertainty about the effectiveness of various mitigation measures has made it difficult to estimate the cost of deep cuts in emissions.

What is not uncertain is that cuts will pose a threat to well-organized high-emitting industries. Prudent negotiators have delayed making commitments and agreed only to treaties that continue business as usual by a more palatable name. Between the delays and superficial compacts, emissions have risen by two-thirds since 1990, and they keep climbing—except for the temporary drop this year when the global economy imploded under the coronavirus pandemic. To stop the rise in global temperature, emissions must be cut deeply—essentially to zero over the long term.

Meanwhile, it is getting harder to agree on collective responses to any urgent global question. The expansion of trade and the diffusion of new technologies have undermined U.S. geopolitical dominance and accelerated the rise of China and the Global South while producing a surge in inequality and open mistrust of elites. The World Trade Organization (WTO), founded in 1995, has been paralyzed for more than a decade by the kind of consensus decision-making that hamstrung climate diplomacy. In many other domains, from human rights to investment to monetary coordination, order seems to be fraying. With no global hegemon and no trusted technocracy—welcome changes in the eyes of many—there is no global authority to mend it.

The Great Recession of 2008 exposed the limits of the postwar model of economic growth and revealed the growing divide between those who stand to benefit from rapid innovation and expanding trade and those who, often with good reason, fear both.

The economic shock triggered this year by the pandemic dramatically underscored and exacerbated those divisions. No wonder that fears and hopes about economic revival and responses to climate change, already tightly linked, have in recent years have become densely intertwined politically. For conservatives in many countries, decarbonization is a fraught symbol of the elite, and repudiating climate agreements—including Trump’s snubbing of the Paris Agreement—is a way to reassert the primacy of national interests after decades of unchecked globalism. For progressives, meanwhile, the need to reconcile sustainability and inclusive well being finds expression in calls for massive public investments such as a Green New Deal. That vision has found only tentative success in only a small fraction of the global economy, one that accounts for a small and shrinking slice of global emissions.

Climate diplomats assumed that solutions have to be global from the start. We should instead piece together partial successes at many different scales.

But this record, bleak as it is, is not the whole story. Alongside the string of make-believe global climate agreements and false visions of sure-fire solutions are significant and promising successes in many other domains—and we can learn from them in the fight to rein in warming. Consider just three examples:

- The Montreal Protocol, an international treaty first crafted in 1987, has put the planet on the path to eliminate gases that destroy the ozone layer and themselves often contribute to warming.

- The California Air Resources Board (CARB), founded in the late 1960s to respond to smog choking Los Angeles, works in rough concert with car companies and the makers of pollution-control devices to tighten standards for vehicular emissions without imposing unworkable goals along the way. CARB and other California regulatory agencies have accelerated development of the electric car and other innovations, demonstrating that even in the United States regulation can push technology in the direction of public interest. Together these policies anticipate key elements of a green industrial policy.

- The Water Framework Directive (WFD) of the European Union induced extensive experimentation with new forms of river-basin and watershed governance that, twenty years after passage of the law, are connecting national, regional and ground level decision-making to make tangible progress on one of the most vexing water pollution problems—the runoff of agrochemicals and animal wastes from farms.

From the global to the local levels, then—and at every level in between—models of effective problem solving have already emerged and continue to make progress on issues that, like climate change, are marked by a diffuse commitment to action but no clear plan for how to proceed. These efforts work in countries as diverse as China and Peru and for international problems as diverse as protecting the ozone layer and cutting marine pollution. They address challenges as intrusive and contentious as any that arise with deep decarbonization, and they tackle challenges whose solutions require unseating powerful interests and transforming whole industries.

These efforts work by acknowledging up front the likelihood of false starts and overreach, given the fact that the best course of action is unknowable at the outset. They encourage ground-level initiative by creating incentives for actors with detailed knowledge of mitigation problems to innovate, then converting the solutions into standards for all. But they also enable ground-level participation in decision making to ensure that general measures are accountably contextualized to local needs. When experiments succeed, they provide the information and practical examples needed to mold politics and investment differently—away from vested interests and toward clean development.

We call this approach to climate change cooperation experimentalist governance. It is sharply at odds with most diplomatic efforts that have so far failed to make much of a dent in global warming. Since climate change is by nature a global problem, the architects of global climate treaties assumed that solutions also have to be global from the start. Since cutting emissions is costly, and each nation is tempted to shirk its responsibilities and shift the costs to others, climate diplomats assumed that no one would cooperate unless all are bound by the same commitments. From those assumptions came the requirement that climate change agreements should be global in scope and legally binding. At the same time, the United Nations General Assembly—the legal body that authorized in 1990 what became the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the parent to every global climate agreement since—asserted that no climate agreement should intrude on any nation’s sovereignty. By this logic, the UNFCCC requires binding consensus among all sovereign members—a global compact that allows formal global choices no more ambitious than what the least ambitious will allow.

Jessica Green says:

Popular protest has reinforced this global gridlock.

But what if, extrapolating from the examples above, the only practical way to get to a workable global solution is to encourage and piece together partial ones? What if the best way to build an effective consensus is not to ask who will commit to achieving certain outcomes no matter what, but instead by inviting parties to start by solving problems at many scales? And what if rewards and sanctions were designed to make it risky for reluctant innovators not to join in when mitigation efforts begin—and then, when advances are consolidated, very costly for less capable actors to delay improvements that are demonstrably feasible?

In short, what if a global approach with binding commitments can and should be the outcome of our efforts, not the starting point?

An Exemplary Success

To get a fix on what an experimentalist approach to governance might mean, concretely, for limiting global warming, consider again the Montreal Protocol, by many measures the single most effective agreement on international environmental protection. It demonstrates that it is possible to catalyze and then speed the broad diffusion of the kinds of innovation in products and production processes needed to alter industries, albeit at a scale much more modest than the disruption implicated with deep decarbonization.

Crafted in the late 1980s, the protocol was ahead of its time. Then and now, everyone agreed that Montreal was effective in protecting the ozone layer, but the reasons for its success were misunderstood by those who immediately used Montreal as the model for climate change diplomacy in the 1990s. The UNFCCC was created in its image without adopting any of the machinery—especially the sector-based systems for advancing innovation—that explain why Montreal worked. Montreal’s central place in both the old, ineffective world of climate change diplomacy and its exemplary role in the emerging one of experimentalist governance makes it a good vantage point from which to look ahead to an institutional architecture that takes uncertainty for granted—making it a spur to innovation rather than a cause of gridlock.

Beginning in the 1970s, scientists detected chemical reactions thinning the atmospheric ozone layer that protects most life on earth from ultraviolet radiation. The cause was traced to emissions of chlorofluorocarbons (and later other chemicals, including halons) that were then widely contained or used in the manufacture of many products, from aerosol sprays to fire extinguishers, styrofoam, refrigeration and industrial lubricants, and cleaning solvents. After more than a decade of contentious debate two linked treaties, the Vienna Convention (1985) and the Montreal Protocol (1987) created the framework for a global regime whose governance procedures were elaborated in the following years.

The core of this vision is a schedule to control and eventually eliminate nearly all ozone-depleting substances (ODS). The measures are reassessed every few years in light of current scientific, environmental, technical and economic information, and the schedule was adapted as necessary. The periodic meeting of the parties has broad authority to review implementation of the overall agreement, and to make formal decisions to add controlled substances or adjust schedules.

Problem solving in the regime is broken down into sectors that implicate similar technologies—solvents, plastic foams, refrigerants, halon fire-extinguishing agents, crop fumigants—and guided by committees representing industry, academia, and government regulators. The committees organize working groups of ODS users and producers to review and assess efforts, mainly in industry, to find acceptable alternatives. The reviews look at key individual components as well as whole systems—for example, assessing whether a refrigerant that depletes the ozone layer can be replaced by an analogous and more benign alternative, as well as whether refrigeration systems that utilize these new chemicals can work reliably and at acceptable cost. Pilot projects yield promising leads that attract further experimentation at larger scale, allowing the committees to judge if the nascent solution is robust enough for general use.

If this search comes up short, the committees and their oversight bodies authorize exemptions for “essential” and “critical” uses or extend timetables for phase-out. When the use of ODS was phased out in the metered dose inhalers (MDIs) that propel medication into the lungs of asthmatics, for example, the sectoral committee consulted doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and device manufactures country by country to determine substitutes and transition schedules that met the safety and efficacy requirements of patients. When firms invented an array of alternative MDIs using benign propellants, the committees put the industry on notice that the old methods would be banned. Innovative firms had a strong incentive not to be left out and persistent laggards faced exclusion from the market.

Over time, an amendment procedure allowed additions within the existing categories of coverage and also brought new categories of emissions under control. The boundaries around “sector” were adjusted as the properties of each class of ODS was understood and as new sectors were implicated.

Membership in the Montreal Protocol expanded sharply as well. Initially the Protocol focused on industrialized countries, as they had the highest consumption of ODS and were most compelled politically to stop ozone thinning. But use increased rapidly among developing countries, and to encourage their participation in the Protocol they were allowed to extend their compliance schedules. As a further incentive, essentially all costs of compliance for developing countries were paid by a “Multilateral Fund” financed by the rich countries—costs that included not just the new technologies but also the local administrative capacity needed to oversee preparation and execution of comprehensive regulatory plans for phasing out production and use of ozone-destroying chemicals sector by sector. Simply making new technology available would not will these benign alternatives into use—local contextualization was essential, and the fund helped build that capacity. Administratively, the fund is probably the best managed funding mechanism in the history of international environmental governance. Politically, it helped transform the ozone problem from one with guaranteed deadlock—developing countries did not want to bear all these costs themselves—into one that was more practical politically.

The Montreal regime operates against the backdrop of vague but potentially draconian penalties for governments and firms that drag their feet. For the western governments that initiated the regime, such as the United States, those penalties were electoral. (Those were the bygone days when the United States was a reliable leader on global environmental topics.) For the industrial firms that made the noxious substances, the penalties were about brand value and license to operate. DuPont, the most visible of these firms, broke ranks with the rest of industry to demand a phaseout; destroying the ozone layer was a big liability for a firm that made most of its money in other kinds of chemicals. (It helped that the alternatives might prove more profitable.) Once there was one innovator, it was too costly for others to lag behind. And in countries that actively undermine the Montreal Protocol—Russia at first but others later on, including India and China—the penalties were threats such as trade sanctions that came from other powerful governments, mainly in the industrialized world, that wanted Montreal to work and also wanted to make sure their home industries would not be undercut by violators overseas.

Designing for Uncertainty

The features of the Montreal approach that make it a good model can be captured in a handful of linked design principles. These principles describe a distinctive cycle of decision making well suited to domains, including climate change, marked by great complexity and uncertainty.

This approach starts with a thin consensus among an open group of founding participants motivated to act. Precise definition of problems, let alone the best way to respond to them, is unknowable at the outset, but there is enough agreement on how to get started. For its part, the Montreal Protocol was based on an initial agreement that ozone thinning was a problem that must be stopped, and that a first step would require cutting in half the most widely used ODS by 1998. At the time there was no agreement on the magnitude of the risk, the feasibility of finding particular substitutes by certain dates, or even whether 50 percent cuts were the right goal. Consensus thickens with effort, however, and new knowledge demonstrates both what is needed and which actors are capable and trustworthy. Participation is open, in the sense that new actors outside the circle of founders are invited in as their experience and expertise becomes relevant to addressing core problems.

In this scheme, actual problem solving is devolved to local or front-line actors—those most likely to have the kind of experience and expertise that embodies unanticipated possibility and unsuspected difficulty. Under Montreal, the most essential ground-level work has been technological and performed by industrial enterprises developing and testing new chemicals and equipment along with local regulators that figure out how this equipment will operate in real world conditions—for example, how MDIs can meet drug safety standards.

This local problem solving is regularly monitored by a more comprehensive body. In the case of Montreal, assessment panels and sectoral committees periodically take stock of local problem solving and help codify lessons. Monitoring is typically implemented by peer review: actors with overlapping but distinct areas of expertise and experience evaluate particular projects against others of their kind. The Multilateral Fund monitors projects in developing countries and updates pooled knowledge about what actions cost and whether they work—vital information because each time Montreal parties adjusted or amended regulatory obligations, they also needed to update the funding plan. These routines help spot and scale successful innovation and make it easier to nip budding failures. Just as initial, broad understanding of problems is corrected by local knowledge, so local choices are corrected in light of related experience elsewhere.

Comprehensive review leads, in turn, to periodic adjustments and redirection of means and ends. From a distance Montreal looks like a regime that always ratcheted commitments tighter, but viewed close up, it becomes apparent that progress was less linear. Goals were periodically relaxed through exemptions and deadline extensions when problems proved unexpectedly hard. Science helped identify broad goals, but the pace of on-the-ground problem solving—along with what the parties were willing to spend in the MLF and other funding mechanisms—determined compliance deadlines and the timing of additions to the list of regulated substances. Periodically, a centralized assessment panel takes stock of the lessons and offers a plan for how emission controls could be adjusted, the benefits to the ozone layer, and what it would cost.

A distinctive combination of penalties and rewards incentivizes both public and private participation in this type of regime. By rewarding leaders to bet on change, they make it risky for laggard firms and government to bet against it. This “penalty default,” as it is known, destabilizes the status quo: obstruction becomes the riskiest bet of all. And once the logjam of current interests is broken, shifting the question from whether change is possible to how it can be implemented in diverse conditions, failure to keep pace is viewed more as a symptom of ignorance and incapacity than an expression of selfish cunning.

The initial form this feedback effect takes is to call attention to shortfalls and offer assistance, not punish wrongdoing. Only when misbehavior persists, and comes to seem incorrigible, does the reaction become draconian: actors that repeatedly prove unwilling or unable to improve are threatened with expulsion from the community, typically by being excluded from key markets.

These principles are unfamiliar to the worlds of the global climate diplomacy and the academics supporting them. But they are not alien to regulators, firms, and NGOs that have stumbled onto ways of working together to solve problems. They have discovered that the only way to move beyond the status quo is to destabilize it and then learn, quickly, to use the daring and imagination that bubble up in the open space to develop better approaches.

Experimentalist Governance Hidden in Plain Sight

To understand why this experience—so familiar to regulators and firms working on ground-level problem solving—has not translated easily into international efforts, it is helpful to take a closer look at conventional assumptions, rooted in the experience of stable times, that have tended to guide policy choices.

The most consequential of these is the expectation that organizations are either top down or bottom up. Top-down organizations are bureaucracies of the kind we associate with big corporations or big government. Precise goals are set at the top and translated into detailed rules or operating routines to direct execution. Frontline workers apply the rules or follow the routines; middle managers see that they do, or make ad hoc adjustments as necessary. Bottom-up organizations, in contrast, seem hardly like organizations at all: they are forms of coordination that emerge as actors—on equal footing, left to themselves, and given enough time to suffer the consequences of their mistakes—eventually master common problems.

Paris was a victim of this top-down, bottom-up dichotomy. The Paris meeting was convened in the recognition that top-down climate organization, culminating in the Kyoto Protocol, had failed. Parties to Paris took that failure to mean one had to embrace bottom-up. But the opposite of a failure does not make a success. Bottom-up organization without direction and discipline is merely a recipe for churning and inaction.

By contrast, experimentalist governance is neither top-down, like a hierarchy, nor bottom-up, like a self-organizing group. It is both, in turn, as lower levels of institutions correct higher ones and vice versa; we might just as well say it is neither. Mindful that climate change actors are too heterogeneous in their interests and capacities for self-organization, it imposes top-down framework goals and penalty defaults to give direction to bottom-up invention. And it provides incentives both to capable, potential innovators and to less capable, potential laggards to encourage advances that are ultimately workable for all. This combination of seemingly incompatible features makes experimentalist governance especially suited to areas like climate change that carry a significant degree of uncertainty.

The second and closely related false dichotomy that has crippled progress on climate change is the choice between technocracy and democracy. In this vision, organizations are either hierarchically controlled by technocrats and managers asserting or pretending to expertise, or else they are democratically accountable to their members and other stakeholders. Paris, in this sense, rejected the technocracy of global diplomatic climate summitry in favor of commitment to the workings of domestic politics in member countries.

One of those who saw past this dichotomy was the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey. Dewey took uncertainty and change as the dominant problems of political life and the need to adapt institutions to new circumstances as the continuing challenge to democracy. The response, he argued, was to explicitly acknowledge the fallibility of current arrangements and to make concrete problems the trigger to adjustment of methods and the clarification of goals. But he cautioned that collaborative investigation of alternatives can only be effective if it integrates the knowledge of experts and the experience and values of citizens, for it is the citizen who knows best “where [the shoe] pinches, even if the expert shoemaker is the best judge of how the trouble is to be remedied.” The broad participation of stakeholders in the Montreal sectoral committees provides a glimpse of how such cooperation can work. As trust in elites frays in our democracies and decarbonization reaches deeper into everyday life, this kind of working collaboration between shoemakers and shod is increasingly important. It is how systems of governance—even at the international level—will earn and retain greater democratic accountability.

Beyond Paris

Where does this leave us? Experimentalist governance provides a set of tested principles to guide construction of regimes that do a good job of managing problems steeped in uncertainty when conventional organizations can’t. International diplomacy such as the Paris Agreement does have a role to play, but a considerably smaller one than its enthusiasts think. The agreement itself acknowledged that the UNFCCC had come to a diplomatic dead end on emissions targets and timetables in the Kyoto Protocol. Paris also did away with the distinction, codified in Kyoto as part of the price of maintaining consensus, between developed countries, responsible for financing the costs of decarbonization, and developing counties, who were essentially exempted from all obligations. Paris welcomed local initiative and innovation from all. It lets individual countries set their own commitments—in the agreement’s jargon, “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs)—with, in principle, regular adjustments aimed at ratcheting the NDCs tighter.

On its surface, then, the Paris commitment to decentralized reliance on NDCs and periodic reviews would seem to welcome, even embody, experimentation, review, and adjustment. But in reality Paris is hamstrung by its reliance on sovereign NDCs and a “rulebook” that makes impossible the intrusive review and scrutiny needed for any system of governance oriented around adjusting ends and means in light of experience. Information in Paris is organized by country, but one of the central lessons from the Montreal experience is that the real work of running experiments and identifying solutions gets done in sectors and subsectors of the economy. The way forward is instead to work sector by sector, within institutions that have the ability to apply experimentalist governance.

With regard to warming-related emissions, in particular, it is useful to distinguish two types of sectors. The first is comprised of globalized and highly concentrated industries, such as aircraft, steel, cement, auto, gas, and oil, whose products or production methods are subject to international standards. Deep decarbonization in such sectors entails risky and costly innovation at the frontier of technology, often driven by penalty defaults. International cooperation is appealing to firms under these conditions because it allows them to pool in some measure knowledge and risks—the Swedish steel maker bets on one radical alternative to current methods, the German another, and periodically they carefully compare notes—and because by demonstrating the feasibility of alternatives they can raise standards and protect themselves against cut-throat competition from firms that continue to produce the traditional way. Thus Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping company by fleet size and cargo volume—and thus the firm best positioned to gain from successful advances—coordinated, inside the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a series of technology demonstration programs co-funded with governments and linked to proposals for new standards. Because cargo ships are long-lived and hard to change once built, Maersk also undertakes to work with those same governments to gradually align equipment and local standards to superior solutions, demonstrating the workability of many paths to improvement and making it easier for other IMO members to join in.

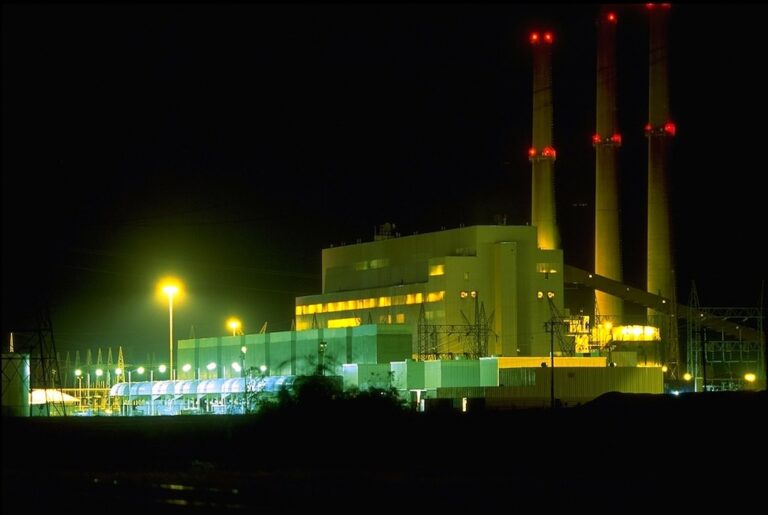

At the opposite extreme are sectors such as residential and commercial construction and power grids incorporating clean energy sources. Production is largely for local markets, using many local inputs, even if key components like wind turbines or nuclear fuel or flooring materials are global commodities; standards are more likely to be local and national than international. Integrating renewables on California’s grid is different than doing so on India’s, even though both buy solar panels from the same global market. Cooperation can accelerate emissions reductions by pooling learning: even if solutions are quintessentially place-based in this case, they typically result from the re-elaboration of innovative techniques developed elsewhere. Knowing where to start and what doesn’t work under conditions similar to one’s own are invaluable.

In between are hybrid cases, such as forestry products or palm oil, where inputs are predominantly local but markets—and hence the standards, backed by penalty defaults, controlling access to them—are international. Reducing illegal logging or burning forests to clear land for agriculture requires reaching deep into local economies, often under limited control by the national state, to give small producers lucrative and stable alternatives to the current, environmentally destructive ones. Progress here is slow, but it continues.

Paris can’t guide, much less participate directly, in sectoral experimentation at the technological frontier or in the elaboration of place-based solutions. But there has been a profusion of problem-solving efforts on these lines within other forums, often in some measure informed by experimentalist principles. There is, if anything, a surfeit of national and international organizations directed to these tasks. The challenge for international cooperation on climate change isn’t creating new sectoral institutions as much as identifying and coordinating the efforts of those that do or could work.

While Paris has little to contribute to this process, it does serve one essential and exclusive function. It is the most legitimate institution in global politics where climate change is discussed; it sets goals that, while probably impossible to meet, are widely agreed as a starting point. Its presence authorizes governments, firms, and NGOs to punish, in the name of Paris, actors that drag their feet. Without Paris it would be much harder for protesters to rattle companies that cause big emissions and push governments to act on climate change. These are the penalty defaults that destabilize the status quo and motivate innovation.

A New Beginning

As we write, the United States is still engaged in a momentous election. No matter the ultimate result—whether the Democrats take the Senate—we must build institutions for learning under uncertainty as rapidly as possible, for global agreements will not be the engine for change.

The Biden administration will rejoin the Paris Agreement—one of the easiest decisions the new administration will make, and far from the most consequential. After that things get difficult. Because Washington remains deeply polarized, climate activism will focus on aggressive administrative action—uncomfortably akin as a matter of administrative law to some of Trump’s expansive use of executive authority—to increase pressure on firms in key industries to cut emissions. A further consequence will be redoubling efforts to build place-based solutions outside Washington, D.C.—for example, accelerating the ongoing shift to renewables and other zero-emission electric technologies in power grids, where policy and investment decisions are entangled in state politics. The more affordable and reliable these solutions, the easier it will be to overcome tenacious political opposition.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge will be dramatically increasing the resources available to address climate change. We will learn what is possible soon enough. And even if the funding efforts succeed, the question remains whether good intentions will lead to good deeds. There are long lists for big new investments in clean energy (and in many other areas as well), along with flowing plans for regulatory reform—ideas that travel under many names, including the Green New Deal, and are aimed not just at cutting U.S. emissions but also building industries of the green future. Yet these proposals, so far, are strong on mandates and vision and often silent on governance.

It is in connecting ideas to action—and keeping them connected amidst uncertainty—that the lessons of Montreal come to bear. They show how, starting with a thin consensus on goals, experimentalist principles can link innovation at the frontier with on-the-ground problem solving in a way that greens the economy without asking the impossible of producers or consumers. Paris showed that we could learn, if incompletely, from the failures of orthodox policy to address climate change. It is now long past time to show that we can learn from our unconventional successes as well.