Paradise Park

Allegra Goodman

Dial Press, $24.05 (cloth)

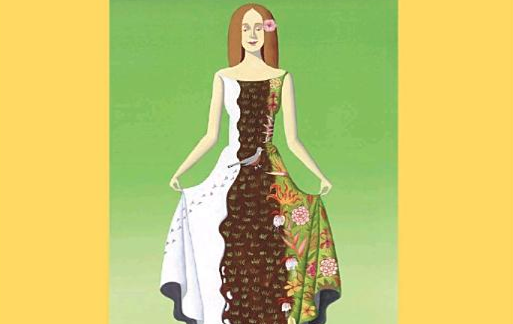

Allegra Goodman's second novel, Paradise Park, is a cross between a Spanish picaresque novel and an Augustinian spiritual quest. It follows Sharon Spiegelman, a 1970s flower-child orphan, over a seventeen-year search for meaning. As the book opens, Sharon wakes in a "fleabag in Waikiki," flooded in light, and feels the loneliness of being an insignificant particle against the enormity of God. A twenty-year-old Boston University dropout, Sharon goes west with her folk-dancing partner Gary, a 35-year-old grad student with beautiful arches and a more-profound-than-thou attitude, to pursue his causes. Already in Oregon, things looked bleak: while Gary goes door-to-door for the Sierra Club, Sharon works as a hotel maid. When Gary deems Oregon and then Berkeley to be insufficiently cause-infused, and Honolulu to be insufficiently paradisiacal, he skips on the hotel bill to run off with a rich German woman to Fiji, leaving Sharon too broke to contemplate her vision of the divine.

Over the years, Sharon wanders from one dead-end life to another in a bumbling quest for God. Her loopy, funny voice is a dead-on mix of desire and ignorance. She volunteers as an unpaid intern on a migratory bird research expedition, expecting a co-author credit on the article the professors will publish. With her next boyfriend, a Christian Hawaiian, she catches cockroaches in a junkyard to be sold for electroplating. After Kekui's family excommunicates him for seeing her, they grow pot for a year in a government-owned jungle. A decade of menial jobs ensues: Sharon works as a temp secretary, a cashier at a Hawaiian fast-food restaurant called Mambo Zippy's, a practice patient for medical students, a clerk in a jewelry store run by a couple of born-agains; her dream-job is a "very hard-to-get" position as a waitress in a bakery. From her jungle shack she moves to a termite infested cell in the YMCA and from there to the couch of a women's studies professor, whose girlfriend accuses Sharon of driving a wedge between her and their cat. There is the filthy, decrepit house of drug dealers Baron—a depressed ex-football player—and T-Bone—"a comer" who is "into the bodybuilding scene." And four months in a silent monastery. In the hilarious opening scene at the co-op house where she spends seven years, we are treated to a three-ballot house meeting about whether Sharon can bring her cat. Sharon questions whether it is consistent for her biologist-roommates to support animal rights while discriminating against certain types of mammals.

In typical picaresque style, Goodman builds a broad depiction of society by pitting her heroine against a vast succession of people and institutions. She renders a perfect-pitch portrait of the lost generation of 1970s hippies, both the zealous, earnest grandiosity with which they intended to remake the world and the aimless desolation induced by repudiating one set of conventional ties after another. Goodman satirizes the naïveté and narcissism of that era's utopianism with enormous wit. Sharon has multiple epiphanies, all recounted with lots of exclamation points. While she is studying religion, Gary writes to say he is in Jerusalem, reading ancient texts and finding "the key." Sharon writes back, "I believe in symmetries in the universe. Correspondences!"

The funniest parts of this very funny book are Goodman skewering the pettiness and reductionism of so much of human spiritual searching. The Hawaiian Christian family of Sharon's boyfriend spends four hours in church each Sunday humming hymns together, then icily dismiss her as a haole (white) colonial usurper out to destroy their world and son. At the natural foods store where she goes to work in order to clean up her diet and mind, her boss is a "semiprofessional surfer chick named Kim." The monk who leads her in Dzogchen meditation is a tight-ass former lawyer who barks at her to stop interrupting his lectures with questions; the rituals of starvation and silence leave Sharon hungry for food and conversation. She returns to university to study religion under a professor who announces that his course is not about the contemporary relevance of religious ideas: texts are not about us, he explains, but about themselves. He utterly fails to engage his student's burning questions, repeating only, "This. Is not. A research paper." Fleeing academia, Sharon makes a mid-semester pilgrimage to Jerusalem; instead of giving her "the key," Gary sticks her in an intensive course on Jewish laws with a professor who is "about two hundred years old" and teaches dietary restrictions like a Nazi. ("Milch," she says, hacking the air in half with a karate chop. "Fleish.") Back in Hawaii, a chance meeting with a rabbi leads her to a synagogue, where she is invited to reconnect with her joy by teaching Israeli folk dancing; after six years, she is performing with a bunch of overweight ladies who have not absorbed the simplest steps.

The novel's central metaphor is Paradise Park, a bird park where one ill-suited boyfriend, a violent marine who calls Sharon "his lady and his princess," takes her. Sharon, who has spent a summer observing real birds on a remote archipelago, is disgusted watching these captives soar up into their forest canopy, only to hit the wire mesh cage. While everyone is clapping hard for "the African gray's rendition of 'Yellow Bird,'" she walks out. Though the birds live in harmony, all their basic needs taken care of, Sharon wonders whether a true utopia can have its structure imposed from the outside. "A real paradise," she says, "that would have to come from inside the birds themselves; that would come from their own hearts." As she flies here and there, Sharon is frustrated by an inevitable human dilemma: we seek paradise and freedom, only to find ourselves entangled by the controlling formal systems all utopias must impose.

Over seventeen years, Sharon's soarings come to collide less with the confines of human-made religion and more with the cage of her own ignorance. Sharon is the epitome of those 1970s idealists who refused to understand that the real world's consistent failure to respond properly is not the world's fault, but rather a result of an unwillingness to learn the skills required to make it respond. Goodman's irony in dealing with the narrator's ignorance is masterful. Sharon is angry and bewildered when a plea for money to her father, replete with fabricated accomplishments, inspires no generosity; angry when the ornithologist-professor refuses to make her a co-author on the research paper about their expedition; angry when her religion professor refuses to accept a meandering fourteen-page letter she has written about her mid-semester Jerusalem pilgrimage as her final research paper. She is so hungry for answers that she latches onto any hint of God, rather than accepting the need for a sustained apprenticeship. A true picaresque heroine, Sharon fails again and again, seeing everyone's faults but her own.

At the same time, a terrible undercurrent of sadness haunts Sharon's cheery accounts of salvation and disappointment. She has as tragic a childhood resume as you could ask for: early on, her father leaves and remarries; at eleven, her only sibling, a beloved older brother, gets killed drunk driving. When she is thirteen, her alcoholic mother abandons her in the house they share with no explanation. Sharon goes to live with her stepmother and father, who lectures her on how hard she has made his life. At Boston University, she falls into drug-dealing to make ends meet after her father, a BU dean, refuses to provide her with enough financial support; when she is caught, he works assiduously to ensure her expulsion. (His letters refusing assistance are gems of logical cruelty.) But the traumas that underpin her lost searching are mostly skimmed over. In the present, Sharon downplays her past and tells cheery lies about her family, amplifying the subtext of desperation beneath the breathy affirmations of her latest situational fix.

What begins as a vision of light coalesces into a vision of God in the form of a surfacing whale. But only at 35, when she meets a twenty-year-old Bialystoker Hasidic couple who have moved to Hawaii "to bring Yiddishkeit to Honolulu," does Sharon encounter a structure with which to engage. Her current dead-end relationship and job in tow, Sharon begins to study. She grouses at some of the traditions, like separating the men and women during study, but loves the overflowing Shabbas feasts the couple proffers. They introduce her to the Tashma, a kabalistic text not about "cooking utensils" but "spirituality and magic." Goodman telescopes the next three years of Sharon's growth: still feeling confined by Judaism's rules and requirements, she is seduced by its poetry and light. While one part of her is thinking, "Run for your life!" another thinks, "Wait. Wait, just let me finish this chapter."

This sort of peripatetic Bildungsroman promises a deepening that Goodman only partially delivers. The author eloquently documents Sharon's basic lesson, her shift from believing she has a right to succeed in being a whole, decent, fulfilled person, to the understanding that such success is a privilege, hard earned by the very few. (Her ironic name for the band she and her husband form at the conclusion is called "The Refusniks.") But, perhaps because ridiculing human folly is easier than depicting the moment where Augustine sits down under a tree and converts, Sharon's voice never quite grows into that of a mature 38-year-old woman; the Judaism she embraces looks a bit like the cult that sticks where others haven't. Still, the wonder of this novel is Goodman's unsparing depiction of the failings of religion, even as she insists on its power to move and heal.