Of the hundred protestors gathered outside the courthouse for Father Christian Von Wernich’s trial last July, few were born at the time of the priest’s alleged crimes. Mostly students, they carried banners for dozens of organizations—the Communists, the Peronist Youth, the Socialists, and other university groups. Images of Che—Argentina’s best-known expatriate—were scattered throughout the crowd. A murga troupe’s drumbeats accompanied chants for “justice” and “punishment,” though firecrackers often interrupted the singsong display. Members of the press engulfed the victims’ lawyers to record canned slogans of “memory, truth, and justice” for the TV news and the morning papers. When Von Wernich first took the stand, protestors chanting “murderer” outside the courthouse temporarily drowned out the proceedings.

Inside the La Plata courthouse, brimming with spectators, journalists, and photographers, there was near silence. One could almost hear judge Carlos Rosanski’s voice without the aid of his microphone. A wooden cross hung on the wall behind as he spoke, managing the first day’s session with measured words. Two dozen women wearing white headscarves with the names of their “disappeared” children embroidered in blue—invited guests of the court—sat patiently. They listened almost motionless, save an occasional tear, for nine hours as the clerk read the case’s dossier. Von Wernich faced seven counts of murder, thirty-one counts of torture, and forty-two counts of kidnapping, all committed between 1976 and 1977.

Entering the courtroom handcuffed, escorted by three armed guards, Von Wernich, sixty-nine, looked more like a frail grandfather than a genocidal maniac. Years had pushed the skin around his eyes downward, narrowing his gaze. He was nearly bald. The bulletproof vest he was wearing crammed his priest’s collar into his neck.

Von Wernich enjoyed most—though certainly not all—of the procedural protections denied his victims: a presumption of innocence, the right to counsel, and a chance to respond to the charges against him. But, throughout the four years it took the government to marshal the case, he sat in prison in “preventive” detention.

As the trial progressed, the crowds dwindled—no protestors showed up on the second day of trial, and soon empty seats outnumbered the specators. The evidence, however, remained. Von Wernich signed the baptism certificate of a girl born in a clandestine prison, whose mother was murdered at his orders. He encouraged torture victims to “testify, for the sake of god and country,” perverting the confession into an interrogation tactic. Under a Nazi flag, he witnessed the torture of Jewish journalist Jacobo Timerman, whose suffering became an international symbol of the abuses of the Argentine military government. For most of the period after the dissolution of the dictatorship, Von Wernich lived in Chile under an assumed name and worked as a priest in a small fishing village. The archconservative Argentine Catholic Church, complicit in the atrocities, coordinated his flight from Argentina.

On October ninth the protestors returned to hear his sentence: Von Wernich was convicted on nearly all counts “under the mark of genocide.” The crowds inside and outside the courthouse broke into celebration, singing, lighting firecrackers, some burning effigies of the priest. After thirty years, the saga to bring Von Wernich to justice was over. Meanwhile hundreds of other defendants were waiting to see how their own pending trials would end.

From 1976 to 1983, Argentina was ruled by the most repressive dictatorship any South American country has ever endured, and the Dirty War was its clandestine campaign against “subversion.” Official government reports estimate that some 14,000 people were “disappeared” in this campaign: kidnapped by the military, held in secret detention centers, tortured, and, typically, murdered. The junta never acknowledged any illegal activity. Almost no records of the campaign survive.

The trial revealed the systematic horrors unleashed by the military government and forced Argentines to reflect on the roots of their authoritarian past.

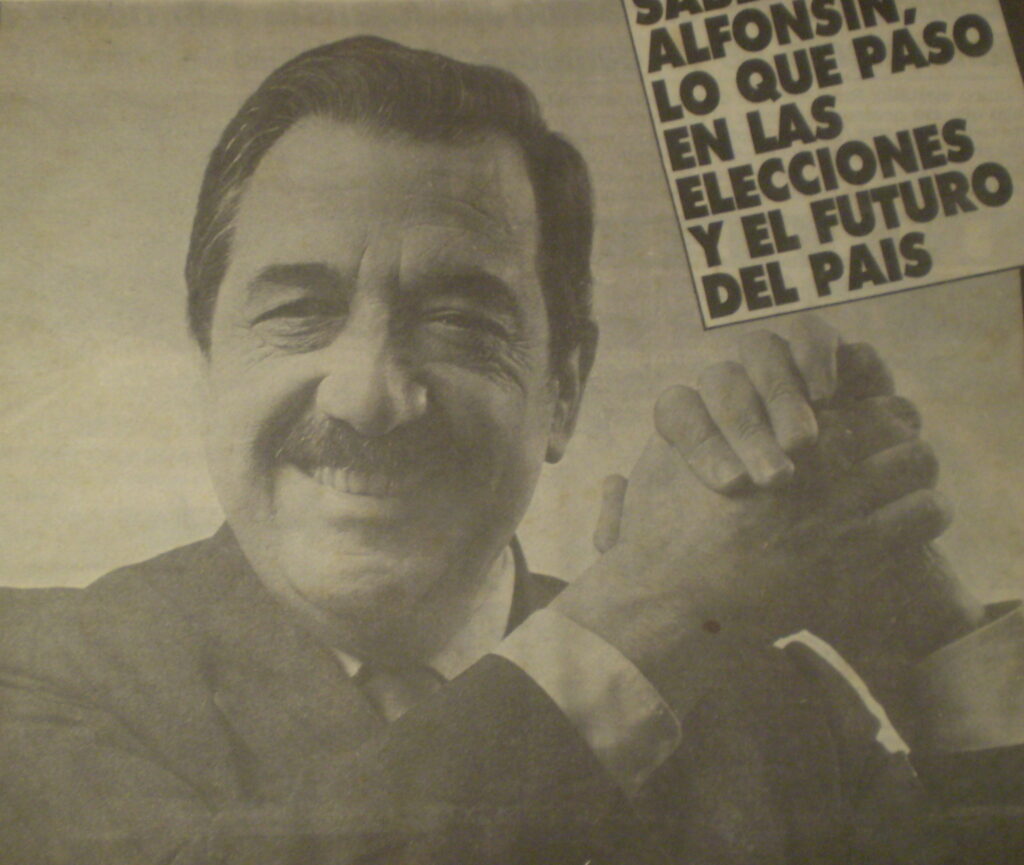

The subsequent twenty-five-year effort to bring perpetrators to justice reveals a painful discord between the impulse to punish past wrongs and the goal of fostering a democratic community, a tension that afflicts all countries after periods of authoritarian rule. In Argentina the justice-seeking began almost immediately after the military regime collapsed amid a slumping economy and a disastrous attempt to reclaim the disputed Malvinas/Falkland Islands from the British. Raúl Alfonsín, the first democratically elected president after the junta’s fall, made history when his government indicted the leading members of the military dictatorship. In the 1985 trial of the junta, five of Argentina’s nine ruling commanders, including General Jorge Videla (the junta’s first de facto president) and Admiral Emilio Massera (the Navy’s ex-commander-in-chief and co-architect of the 1976 coup), were convicted of human rights abuses. The trial revealed the systematic horrors unleashed by the military government, forced Argentines to reflect on the roots of their authoritarian past, and forged a collective witness to ensure that such horrors would never happen again.

But as indictments reached down the chain of command, an anxious military strongly asserted its opposition to further prosecution. Under the threat of another coup—the military had overthrown Argentina’s constitutional government six times in the twentieth century and often played a central role in politics, even if not formally in power—Alfonsín pushed the Full Stop law through congress in 1986, which left only sixty days for new indictments. Alfonsín hoped only a few dozen would follow, which would ease military anxiety and solidify democratic transition. Instead, 400 indictments came in before the deadline. In the days before Easter of 1987, Lieutenant Colonel Aldo Rico staged a rebellion at the Campo de Mayo army base. In response, 400,000 people gathered in the Plaza de Mayo outside the government house in Buenos Aires. On a tense Easter Sunday, facing the prospect of bloodshed and civil war, President Alfonsín flew to Campo de Mayo. Though Alfonsín denies negotiating, the rebellion ended, and by June the Due Obedience law was passed. Due Obedience exculpated mid- and low-ranking officials for their involvement in the disappearances. Together, the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws were a wide-reaching amnesty, ending all but a few of the 400 prosecutions in process.

Toward the end of Alfonsín’s tenure, Argentina was crippled by a hyperinflation reaching levels as high as 2000 percent. Politically unpopular for his perceived capitulation to the military and his failure to reign in the inflation, Alfonsín was forced out of office early and succeeded by Carlos Menem in 1989. After further isolated revolts, Menem issued blanket pardons in 1989 and 1990. Though most Argentines found the pardons unsettling, Menem recognized that, seven years after the military’s collapse, economic reform had eclipsed the Dirty War in immediate political importance. Equally pragmatic and principled, Menem silenced military unrest in order to protect his presidency and move ahead with economic privatization.

For years human rights organizations challenged his impunity. The Madres (Mothers) de Plaza de Mayo—who began their weekly protests at the height of the junta’s power—continued marching around the Plaza, demanding accountability for the disappearance of their children. Legal organizations brought constitutional challenges. But the combined moral and juridical force of the human rights movement did not prevail. In 1987, the Supreme Court upheld the amnesty laws, and in 1990—after Menem successfully packed the court by increasing its membership from five to nine—upheld the pardons. With the amnesty cemented in law, the transition appeared over. The mothers marched, but no one listened.

Horacio Verbitsky maintains a dark, windowless office a stone’s throw from Argentina’s Supreme Court. The walls are plastered from floor to ceiling with protest posters and flyers from famous jazz clubs like the Blue Note and the Village Vanguard. Placed prominently among all of this clutter, just behind his desk at shoulder level, is a classic Playboy magazine cover. When he speaks, his sentences are never broken by fillers—asi que, como—only a contemplative silence. In addition to being Argentina’s most famous investigative journalist, Verbitsky is president of the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS), the vanguard human rights–focused legal organization in Argentina. In both of these capacities, Verbitsky has played a central role in ending what he calls “the impunity”.

In the early ’90s, Verbitsky was a staple on television news after exposing a large-scale corruption scandal in the Menem administration. Because of his notoriety he was often stopped on the street. During this time, a small, impoverished-looking man approached him one day on the subway. “I was at the ESMA,” he said. The ESMA (The Naval Mechanics School) was Argentina’s most repressive clandestine detention center, where as many as 5000 people died. Assuming the man was a victim (among those who escaped death, many struggled through life haunted by their memories) Verbitsky offered his sympathies. “You don’t understand,” the stranger said, as he handed Verbitsky a portfolio. The man Verbitsky mistook for a survivor, Adolfo Scilingo, had been active in a military “workgroup” as a sailor in the Navy. Angry at his commanders for attempting to justify the violence as the “excesses” of a few underlings, he was ready to go public with his story, indicating that responsibility went all the way up the chain of command. No soldiers or sailors had ever directly admitted their participation in the Dirty War. Scilingo eventually agreed to an interview with Verbitsky, which became The Flight, published in 1995 and later called Confessions of an Argentine Dirty Warrior.

In first-person detail, Scilingo described the executions. Prisoners were injected with a “vaccine” in preparation for “transfer” to a prison in Patagonia. The injection was an anesthetic. The prisoners were then stripped, loaded onto a cargo plane, and thrown out over the South Atlantic, alive. Every Wednesday for several years, forty to fifty prisoners would “go up.” Almost nobody returned.

Confessions made the Dirty War front-page news once again. International pressure mounted on Argentina to reopen prosecutions. In 1996, with domestic channels blocked, Spanish courts began asserting so-called universal jurisdiction, a legal doctrine stating that any country at any time may indict perpetrators for crimes against humanity if their home countries do not. The Spanish courts requested the extradition of Argentine Dirty Warriors. Soon, France, Italy, and Switzerland initiated prosecutions for the disappearances of European citizens.

Though constitutionality dubious, the new law provided political support to prosecutors interested in re-opening investigations from the mid-’80s.

The international pressure bolstered domestic activists. Human rights organizations began arguing for the “right to truth,” which the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights recognized in 1999. This spawned “truth trials”—non-punitive judicial processes hearing and recording testimony on the Dirty War. Simultaneously, the Abuelas (Grandmothers) de la Plaza de Mayo vigorously pursued a claim not barred by the amnesty:the kidnapping and trafficking of babies. Through extensive research, activism, and litigation, the Abuelas discovered eighty children who were disappeared with their parents and raised by military families under forged identities.

The detention of former Chilean dictator Augosto Pinochet in London in October 1998 was also a turning point, symbolizing international opposition to impunity. The next day, Videla and Massera—pardoned for other crimes—were arrested in Argentina for the kidnapping of babies.

Verbitsky says:

With all of this in the background, in the middle of 2000, we didn’t think there were any obstacles—not juridical, not political, not ethical—to challenge all the crimes committed under the dictatorship. This is how we came to challenge the Due Obedience and Full Stop laws.

CELS intervened in a case the Abuelas were litigating against Julio Simon. Simon was a workgroup member in Argentina’s First Army Corps, indicted on charges of kidnapping Claudia Poblete, who was taken as an infant when her parents were disappeared. (Their “crime” had been subversive disability rights activism). After their murders, she was raised by a military family under a forged identity.

As Verbitsky recounts:

The Simon case was very special, because, in one operation, a group of repressors had kidnapped a couple and theirchild . . . The Full Stop and Due Obedience laws prohibited punishment for the disappearance of the parents, while . . . they permitted punishment for the kidnapping of the child . . . All the investigation was done, all the evidence was developed, it was nothing more than a question of law, to decide which law applied. It appeared to us this case would expose these abhorrent laws. How could the law not apply to the disappearance of the parents?

Faced with this paradox at trial in 2001, Judge Gabriel Cavallo declared the Due Obedience and Full Stop laws unconstitutional. Simon was convicted for the murder and kidnapping of Claudia’s parents. He is currently serving a twenty-five-year sentence.

Sporadic indictments against other officers followed Cavallo’s decision. Then, after assuming office in 2003, President Nestor Kirchner successfully introduced a bill annulling the amnesty completely. Though constitutionality dubious, the new law provided political support to prosecutors interested in re-opening investigations from the mid-’80s. Within weeks, 340 people were indicted. In 2005 the Supreme Court concurred with Judge Cavallo’s opinion in the Simon case, giving judicial support to the renewed prosecutions. Last July, the Court overturned a series of Menem’s pardons. In both cases, the Court cited a duty under international law “to prosecute crimes against humanity” despite any legal obstacles that may exist, such as amnesty laws, pardons, or previous court decisions. Von Wernich was the third in this group of several hundred to be sentenced. The vast majority await trial.

Scholars and the courts have expended considerable energy in efforts to justify the outcome of the Simon case. Cavallo’s decision was over a hundred pages long. The Supreme Court’s—comprising seven distinct majority opinions—ran to 353 pages. Julio Strassera, the prevailing government prosecutor in the trial of the junta (whom one would expect to favor the Simon decision) described the opinion as “confused.”

Indeed, from an individual rights perspective, the legal process surrounding the Dirty War has been confused at best. The state has dragged hundreds of people through legal purgatory for a generation. Indicted after the collapse, granted amnesty, pardoned, accused in “truth trials,” threatened with charges of child trafficking, exposed to foreign courts, the defendants once again face the full weight of prosecution.

Perhaps the Simon case was bound to be full of internal contradictions. The legal concepts and vocabulary that have framed Argentina’s pursuit of justice were designed to expound the rules and procedures governments can use to bring criminal charges against individuals. But mass atrocity takes place in a social and political context quite distinct from ordinary criminal behavior. The perpetrators are state agents, not individual citizens, and they often act with the support or tacit approval of large sectors of the population. The crimes are as much collective as they are individual. The length of and commotion surrounding the Simon case reveal the difficulty of applying a set of procedures and laws in a context for which they were not designed. As Strassera also admitted, “From the juridical point of view, it’s difficult, because it certainly seems like the retroactive application of criminal law. But it’s good, at the least, to do justice from a moral perspective.”

Judge Cavallo is at the center of a project to reshape Argentina from the bench. Always dressed to the nines, he makes a habit of showing off his GC gold cufflinks just beyond the wrists of his perfectly tailored suits. His gaze—commanding, pointed—may have suited him better as a Caudillo than a federal judge. But he has the conviction of a man of the bench. He employs a booming voice and combative rhetoric to overcome any lingering doubt about the veracity of his legal opinions.

In discussing the legal criticism of his decision, Cavallo first cautioned me to remember, “This is not Switzerland.” I took his advice to mean Argentine democracy is less than twenty-five years old, so basic principles of criminal law should yield to more important considerations of democracy-building. Yet he rejects out-of-hand the idea that the amnesty laws were passed to “consolidate democracy,” as has been their justification for two decades. “It was an excuse to cover up what happened. It was a political decision to pacify everyone . . . Nobody in the world thought it was the right decision—look at Human Rights Watch, the European courts, Amnesty International, the American courts.”

More fundamentally, Cavallo offered what might be considered extra-legal or social defenses of the Simon decision. First, he says, society has a strong interest in the truth about what happened, which can be uncovered through the solicitation of testimony and the collection of evidence. But after so many truth-generating processes—Argentina’s national truth commission (CONADEP) formed after the transition in 1983, the trial of the junta, and the truth trials of the ’90s—the current round of prosecutions may not reveal much more than is already known. Scilingo remains the only military official to directly admit to his participation in the Dirty War, and, so far, the defendants have refused to speak. Nevertheless, Cavallo points out that advances in forensic technology have opened new channels of investigation. Through DNA samples, the identity of the human remains can be determined. And, as Gil Lavedra, one of the three judges in the trial of the junta, pointed out, “Even if 95 percent of the truth is known, even uncovering a little more of that 5 percent we do not know about is worth it.”

Cavallo is adamant that justice demands punishment, lest the victims’ claims be left without vindication. Yet justice may, at this point, caution against punishment. For the accused, punishment may run against rights of due process in the retroactive application of the criminal law. And for society, the pursuit of justice in periods of political transition may best be served not by focusing on past wrongdoing, but by building enduring institutions for the future.

Cavallo also argues that the trials must proceed so that a memory of the Dirty War can be preserved and act as a check on authoritarian impulses. This was the principal effect of the trial of the junta. But there are other ways to interpret and assimilate the experience of atrocity, such as education and public campaigns. Given the due process concerns surrounding the re-opening of the trials, it is not clear that the courtroom is the best forum to evoke memory.

Cavallo insists that punishment is vital to the creation of public memory. He argues that, without punishment, the Dirty War lingers in the present, preventing victims and Argentina as a nation from adequately dealing with the experience. “The feeling of impunity” keeps the Dirty War present in people’s minds, preventing Argentina from moving past the experience.

Focusing on judges and human rights activists may obscure the real impetus for the new trials. The moving force might be nothing more than raw electoral politics.

As the Simon litigation moved through the appeals process, Argentina was hit by economic crisis. After the government de-pegged the peso from the dollar, the Argentine currncy, practically overnight, lost two-thirds of its value. Argentines found their way of life shattered.

The economic crisis threw Argentina into near anarchy. Que se vayan todos—“everybody go”—became the slogan of daily protests. Five presidents passed through the Casa Rosada in less than six months between 2001 and 2002. When elections were held in May 2003, two candidates emerged from the first round, Nestor Kirchner and Menem (who was running again after four years out of office). Menem won the first round, but it was clear he would not survive the second. Instead of facing embarrassing defeat, he withdrew. Kirchner took office with just 22 percent of the vote.

Part socialist, part fascist, his followers came together through his cult of personality and a transcendent idea of economic nationalism.

Kirchner had built his political career by identifying with the “Peronista” (followers of Juan Perón) activists of the early ’70s. Perón had been president from 1946-1955, but, after a military coup, was exiled from Argentina. All Peronista political activity was subsequently banned. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a new generation of Peronistas emerged—Kirchner among them. Taking to heart Perón’s social-justice rhetoric, they fought as activists and guerillas against the military governments of Generals Onganía and Lanusse, hoping to enable Perón’s return. However, when he finally did, and was re-elected to the presidency in 1973, it was clear that the activists had been used. Perón had always managed to maintain a broad coalition under his “justicialist” doctrine. Part socialist, part fascist, his followers came together through his cult of personality and a transcendent idea of economic nationalism. But after his homecoming, Perón sided with his right-wing followers, and, after his death in 1974, the split within the party turned violent. The left-wing followers—principally the Montoneros—adopted guerilla tactics, and the government, now headed by Perón’s third wife, María Estela Martínez, sponsored ultra right–wing paramilitary forces to fight them. By 1975, the Peronista left was decimated as a fighting force and the 1976 military coup thwarted its political ambitions.

When Kirchner, resurrecting the Peronist left-wing, took office with such low electoral numbers, most thought he would be ineffective. To combat expectations, Kirchner quickly made human rights his political Excalibur. By invoking the images and stories of left-wing Peronistas, he attracted political activists and militants from the ’70s. As the economy improved, Kirchner began to accumulate power, using the centralized budgeting process to keep congressional allies in line. At the zenith of his early power, he successfully moved the annulment law through congress, ensuring that human rights remained a prominent issue throughout his presidency by sparking wide-reaching prosecutions. Waving the banner of human rights was the perfect way to gain electoral legitimacy. His wife, Cristina Fernandez, elected President last October to succeed him, has also taken up this issue.

Kirchner was also fortunate because he was able to appoint a majority of the Supreme Court justices. Though the justices were a professional upgrade from Menem’s “automatic majority,” they were appointed with an eye toward their human rights views. (When Cavallo released his decision, he was sure it would be overturned. Kirchner’s appointments saved it.)

With Kirchner’s presidency left-wing Peronistas found themselves in power for the first time since the transition to democracy. Still angered by the amnesty laws, they used the opportunity to enact political revenge on Alfonsín’s Radical Party by re-engineering the transitional strategy from the ’80s, and actual revenge on the Dirty Warriors who decimated their ranks. One aspect of the Peronista left’s political program was Kirchner’s recent revision of the prologue of the Nunca Más, the 1984 CONADEP report on the abuses of the Dirty War. The prologue set out the theory of “Two Demons,” locating the roots of the Dirty War in the anti-democratic tendencies of the army and the guerillas. It was the standard explanation of the dictatorship, though it offended guerillas to suggest they had any role in provoking state violence. “Two Demons” has now been excised from the text.

Luis Alén is chief of staff for Argentina’s Secretary of Human Rights and in charge of overseeing the trials for the executive branch. The décor of his office shows his affinity for Peronism—a large picture of Evita hangs above his desk, dwarfing the pictures of his family on the opposite wall. A picture of him with Kirchner is also prominently displayed. Alén says, “there is only one demon, state terror.”

In the course of our two-hour interview, I managed fewer than a dozen questions, each of which provoked a Castro-length response. During his series of mini-lectures, he lit up seven cigarettes and took only four drags.

The Argentine people can’t be amnesiacs… Without understanding the past, you don’t know where you are, or who you are because you walk through the world blind…

There’s no way a state can justify breaking its own norms because others breach the law—the fact that the Montoneros used illegal means does not give the state an excuse for its conduct. The state cannot violate its reason for being.

Alén may be correct, but because of practical limitations on investigating crimes committed by the dictatorship twenty-five years ago, guidance is needed, and Alén provides only tokens: “Where there is evidence, we will proceed.” When pressed on the limitations of this strategy he said, “We can’t just pick a few representative cases, this is unfair to the victims… you have to judge everyone.”

He also seems undisturbed that many defendants have spent two or more years in jail pending trial without bail, violating the very human (or civil) rights he professes to uphold. “Nobody facing trial is innocent,” he maintains. “I’ve seen the evidence from CONADEP.”

Most judicial branch officials deny that the process is politically motivated, pointing out that Cavallo reached his decision before Kirchner was elected. But, as Federico Delgado, the federal prosecutor investigating cases against the First Army Corp and Ford Motor Company (accused of hosting a government torture center to combat union organizing), told me, “The judicial system accompanies the political winds. If Kirchner weren’t President, there wouldn’t be trials. To be in favor of human rights now is like speaking well of Al Gore, it’s in style.” Even Carolina Varsky, who litigated the Simon case for CELS, reluctantly admits, “The decision to go ahead politically really helped the process.” She insists, though, that the movement to end impunity has its roots in the ’80s.

Visitors to Buenos Aires’s judicial building on Comodoro Py, where most of the cases against the dictatorship are unfolding, find a bureaucratic stronghold, fortified by miles of paper stacked on metal desks, guarded by young clerks and secretaries scattered throughout the building’s eight floors. Resources are slim. Low-ranking employees have their desks crammed into hallways. The actual guards do little; on several occasions I set off the metal detector at the building’s entrance and none of them flinched.

The building’s location is a catastrophe in urban planning. Bordered by the Retiro train and bus stations and Buenos Aires’s main port, trucks and long-distance buses lug by in constant bumper-to-bumper traffic on the twelve-lane road outside, far from the city’s pedestrian core. The structure is an apt metaphor for the inaccessibility of Argentine justice. Since the Dirty War trials reopened, the process has moved at a snail’s pace. Just four cases have proceeded to verdict. In the meantime, hundreds of accused sit in jail.

Rather than trying individual defendants, trials should proceed against multiple defendants when the evidence against them is similar.

The ESMA case—the largest of the cases now in process, and staffed by just four part-time attorneys—involves a nightmare of evidence. The record is 30,000 pages. Six hundred witnesses are expected to testify against forty defendants. The first oral hearings began October 18th, a year after this part of the case was first presented to the trial judge. Most of the defendants are still waiting for their court-dates. The first defendant in the case was murdered in jail just days before he was to be sentenced.

In poorer provinces, where the repression during the Dirty War was often worse, resources are almost nonexistent. As Judge Daniel Rafecas bluntly put it, “The process moves slowly because we live in an underdeveloped country, so we have the organization and the justice system of an underdeveloped country.”

Just proving that crimes occurred can be immensely difficult. Judge Cavallo knows this well.

We’ve always been confronted by a practical problem: It’s almost impossible to find direct evidence of these crimes. The victims are dead, they were blindfolded, they couldn’t see, they were kept away from . . . the other victims being tortured. The evidence is always indirect. But that doesn’t mean you can’t prove the crime, it just takes the confluence of much more evidence.

The legal questions involved are also arduous. What constitutes torture? Is someone’s presence at a clandestine center enough to support conviction as an accomplice? What constitutes responsibility for torture?

The Public Ministry—a “fourth branch” under the Argentine system, its formal separation from the executive and the judiciary more theoretical than actual—has created the “Unit for the Coordination and Continuance of Cases for Human Rights Violations Under State Terrorism,” headed by Pablo Parenti. “The process moves slowly for lots of factors,” Parenti explains. “In general, the investigative process in Argentina is very slow, it’s very formalized. The roles of the judges and the prosecutors are not often clear.” Unlike the American system in which opposing attorneys do most of the work, the Argentine system dictates that judges control the development of cases. Parenti thinks that if judges left more in the hands of the prosecutors, trials would proceed faster. He has also recommended forming a cadre of full-time prosecutors to handle the Dirty War cases, under the direction of his office.

He, along with human rights organizations, has also proposed consolidating cases. Rather than trying individual defendants, trials should proceed against multiple defendants when the evidence against them is similar, as happened in the trial of the junta. It would speed the process by reducing the number of cases and save victims from having to relive their experiences over and over. As Parenti explains, legal obstacles are not the only hindrance.

There’s still some ideological resistance. It’s not out in the open, but judges and even some prosecutors are slowing the process.

In the capital, it gives a judge social prestige to oversee one of the cases. In other places, it can help combat accusations of corruption. However, it is very difficult to move these cases along where the military and the accused still hold lots of power . . . For instance, in Corrientes it’s very hard. They are bringing a trial against the president of La Rural [Argentina’s powerful cattle industry association]. La Rural in Corrientes is Argentina’s second biggest. There, the accused [Juan Carlos Demarchi] is an ex-military officer who is still very powerful.

Frustrated, Parenti admits, “There might just be a natural end to all of this. The accused might just simply die.”

The far right continues to object to the trials, and defends the actions of the military government as an appropriate, if at times excessive, response to the political violence that plagued Argentina in the ’70s. Cecilia Pando, president of the Association of Family and Friends of Political Prisoners in Argentina (a military support group), recently told the Buenos Aires Herald, “We should just turn the page. It was a regrettable war between terrorists and members of the military who were trying to defend their country.” (Pando was Von Wernich’s only public supporter at his trial. She was expelled for provoking an argument with the Mothers by holding up a picture of a murdered army colonel).

Pando’s solution, however, characterizes human rights abuses as solely political, assuming the appropriate response is through the transfer of power. This conflates the moral significance of the clandestine campaign with a simple policy blunder, failing to condemn human rights violations as impermissibly outside the boundaries of politics.

Recently some liberal critics have voiced concerns too. Jaime Malamud Goti, a legal advisor in the Alfonsín administration and the author of the amnesty laws, challenges the wisdom of bringing the trials today. Goti says he has felt “guilty” for nearly twenty years, believing that the transition was marked by failures. If the government clearly selected just the top brass for prosecution, Alfonsín could have gained political allies within the military. Goti points out, “After Nuremberg, they went after the conspicuous cases, but left some of the worst perpetrators free just to get over it. Within ten years, the process of denazification was done, even though most Nazis walked free.” Ironically, it was the success of the trials in the ’80s and the promise of widespread prosecutions that fueled dissatisfaction since the passage of the amnesty laws.

Goti sees criminal adjudication of atrocity as a tool of democratic consolidation, and suggested that—once that consolidation is complete—it may be politically wise to excuse some members of the old guard, even if they are guilty. Goti admits to a “nagging sensation” that many deserve to be punished, but “they’re all old men.”

So, who is responsible, and what will serve justice? A trial may be ill-suited to the task as it implicitly draws lines of responsibility, blaming the condemned, absolving all others. Furthermore, since many civilians gave tacit, if not explicit, approval to the military regime, a trial may not be the best way to identify the responsible individuals. Goti admits, “Intellectually, I can’t find an answer for these questions—responsibility, praise, blame.” Hardly substantive ideas of justice, he reluctantly admits, maybe simply “emotional reactions.”

Graciela Fernandéz Meijide, whose face is weathered from a quarter century of human rights struggles, has also voiced concerns with reopening the Dirty War trials. Her son, who would now be forty-eight, is among the disappeared. Meijide, a founding member of the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights, was a member of the CONADEP, and was party to a case challenging the constitutionality of the amnesty laws in the ’80s.

Meijide describes herself as a “contradiction.” She lambastes the recent decision in the case of former General Santiago Omar Riveros overturning Menem’s pardons, because the Supreme Court had already held Riveros’s own pardon constitutional. “From the most liberal perspective of the law, you can’t commit double jeopardy, re-judge a decision that’s already been made by the same court, even if it was an awful Supreme Court”—alluding to the “automatic majority” of the Menem court. She sees it as a sign of broader institutional weakness. “You can’t just change everything every time a different sector of society is in control.” Yet, despite her concern with the process, she testified as a witness in the Von Wernich case, saying it was her duty.

When I met with Meijide before the trial, she complained about the political climate.

I’ll go, I’ll testify, the media will jam a microphone in my face, ask me four to five shallow questions, put my face on television, and that’s it. These trials aren’t strengthening democracy. There’s no discussion provoked by these trials. Nobody pays attention to them . . . Maybe for some— the victims, the militares, the politicians—it’s important. But, for the broader society, it doesn’t matter.

(Her prediction was prescient. When I saw her leaving the courtroom, she was stormed by a gaggle of reporters, asked several frivolous questions, and had a few sound-bytes on the evening news.)

What distinguishes a human rights trial from an ordinary criminal trial is its capacity to affect the political structures that fueled the violations in the first place. But Miejide and Goti’s criticisms point out that the trials today simply are not capable of the same impact as those held twenty-two years ago. Other institutions besides the judiciary must shape the human rights–trial process. The press, in particular, must interpret trials of atrocity, demonstrating to the public why repression is, in part, political in nature. This is why the trial of the junta was so successful: each week newspapers published the trial transcripts, which in turn were read and discussed intensively by large sectors of society. By contrast, today’s trials attract little public attention.

Even the character of the press coverage is different, focusing on minute details of each case rather than exploring the political character of the violence. The trials appear as ordinary criminal processes and seem incapable of provoking broader political impact. Though many of the accused undoubtedly committed horrendous crimes, the democratic aspirations of the renewed trials will likely go unfulfilled.

Meijide described the limitations of the undertaking with a story:

I was recently in a car accident, and, out of the wreck, I had my purse stolen. So, for a week, I was dealing with the accident, I was in pain, I had to get new credit cards, get my car fixed. It preoccupied my life. And, Von Wernich! Who cares about Von Wernich? What do you think it’s like if you are unemployed, or without health insurance, or you can’t pay for heating oil. Too much time has passed.