I. The Future . . .

From where is the future related?

II. The Past

That day, that final day, the clouds summoned up new life with the tack and the force of a swollen sea: in a slow and almost imperceptible descent, they were clumped upon the earth, upon the landscape that they now erase and disfigure. Dust, smoke, and the aridness of a long and painful drought. Before: the normalcy of daily rites. Breakfast at home (scrambled eggs with cheese in a flour tortilla. Café con leche. Orange drink.) The ride to school (the bam-bam of the lunch boxes against the bus’s metal surfaces, jolt after jolt, shouts, fights, the arrival). Español. English. Sciences (social and natural). Time to leave (the bam-bam of the lunch boxes against the stair rails, jump-ropers, taunts, shouts, fights, goodbyes). Approaching the car. The silences between the mother and son in the afternoon. A commercial on the radio while faces painted white and laced with almost bloody smiles gather by the window along with a dramatic derrière composed of balloons; fakers and poseurs and the malnourished who walk over broken glass; mothers overwhelmed with children: children with faces painted white who dance under an incipient rain. The voice on the radio anticipates sunny days . . . starting after today. It is interrupted by an urgent announcement. A woman’s thick voice under the effects of hysteria. Marcialito—his eyes looking like those of a fish in a freezer—watches his mother who watches the street, still familiar and calm. A simple gesture changes everything: letting go of the steering wheel to apply a quick yet firm squeeze of his hands. Later, it came, with its lowering throng of clouds laden with heavy and toxic gasses. Thus, though long-predicted, the annihilation came unexpectedly. Also unexpected was that some survived.

III. The Present

Marcialito strolls, saunters, and kicks a rock through the quiet, sallow, dusty air; it flies hesitantly, hangs there, falls next to a colorful, cylindrical object that resonates with a hollow sound. Marcialito pays no attention. He moves on with his short legs and his scuffed and colorless shoes. Pursuing a phantom he does not know. An unsolicited phantom, yet one that will prove to be the key to (the beginning of?) his unsought search. A light wind blows, not strong enough to tousle the stiff green hair sprouting from his head like dry grass. A midday or midnight whistle. Marcialito does not know the difference.

His friends (the majority of them indifferent to Marcialito while Marcialito thought they’re just spoiled and bad-mannered kids, but he misses them now) and their parents ceased to exist on earth on the day of the final day. (The guilty, full of threats, were never very creative with their names, thought Marcialito; but also that their lack of creativity was the least of their shortcomings.) Others like him pass by as well. Though not all of them will undergo what he is about to undergo. Nothing of mythic proportions, nothing memorable if still relatable, describable, explicable. Even certain.

Thus he walks, knocking and kicking about distractedly. A solitary boy among the garbage. He does not cry. He thinks of almost nothing and he makes this deficiency into a virtue and a source of pleasure. Until:

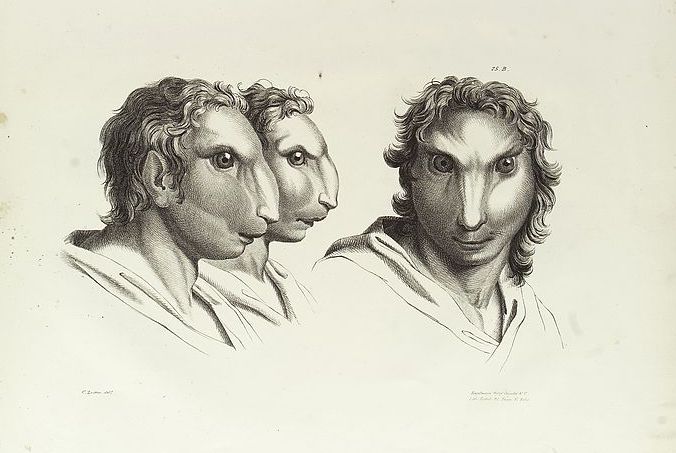

The rock flies, lands alongside a can, and the can moves. There appears, still beneath the distracted gaze of the solitary boy, One blue rabbit. Two. Three. Four. One and Two are larger, as if parents. Three is . . . like him. Four is tiny. As tiny as he feels. Thin (as thin as the needle in the haystack), he folds his aching body and grasps in his bony hand the photograph of One, Two, Three, and Four. He takes a closer look: rabbits with human faces. Humans with the bodies of rabbits. Rabbit-human-rabbit. The wind blows. No longer lightly; it pushes and he falls (the needle in the haystack does), he gets up, recovers his object. He feels an unprecedented urge to run, to seek refuge (from what? from whom?) under a tattered, fading orange awning (which had once served as the entrance to an elegant building that housed well-to-do folks with exquisite taste, though Marcialito ignores all this because he has forgotten it). Once there, with rosy cheeks and anxious breaths, he squeezes his treasure between his hands and his heart. Poor imitations of rabbits; poor imitations of humans. He reflects: he also (I also) is (am) an imitation (an imitation). He doesn’t (I don’t) know of what, of whom. Could it matter?

The yellowish light that bathes him and all the rest slowly begins to disappear, then winks out. Another one, transparent and darker, takes its place. Someone unseen roars, and Marcialito hugs himself. Treasure in hand, and against his chest. A few minutes later, a noisy rain begins to scatter itself across the rooftops. He hears it bursting over the awning. He feels fear. He feels alone. He looks at the photo. The smiling faces. Who are these bodies, rabbits or humans, these broad smiles and bright eyes? The mystery brings the memory of having had memories—when he didn’t know it all (like now, when he knows everything simply because there is nothing to know). For the first time, he feels the urge to look around him. He experiences the risky but always fertile curiosity to know where he is and who he is. He looks at the photo again, and senses a darkness inside himself as profound as that which surrounds him. In the rain, faced with doubt,

A. Marcialito ventures inside a building that used to be a famous toy store. Go to the page: file://localhost/Users/auraec/Desktop/marcialave2.html, or

B. Walk amongst the garbage, guided by a mysterious sound. Go to Section VII, or

C. Tear up the photograph and go to sleep. Your adventure is over.

D. None of the above. Continue reading in a linear manner.

IV. Interruption: The Origin

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, whose red, green, gold, and black vestments are spread across the haunches of their mounts, make their way under a mottled sky and past a raucous, smiling crowd (so noisy that, a few hours before, it had forced Marcel Marceau to talk); teenagers, children, groups of friends, pairs of college students (with beer and cigarette in hand) kissing one another, indifferent to the performance of the Swedish Apocalypse that has come to visit the capital as part of the Festival de Arte Cittadino. Above the chatter, they catch phrases such as: Now even the Apocalypse comes across as spectacle. More than the drama—which, thanks to the authorities, has been left in Swedish without benefit of translation either simultaneous or delayed—it is the risk of a fall from the stilts that causes the public, from time to time, to show some interest, and turn its gaze toward the giant masked figures. Otherwise, the crowd remains unaffected by the valiant efforts of the actors who move with a natural ease across the esplanade.

This afternoon, the street vendors—clandestine proprietors of the esplanade—have packed up their booths and wares; the owners of stores selling toys, shoes, perfumes, and other beauty products have pulled down their metal shutters and joined the animated festival-goers, among whom wander the actors, most of them foreign, and who, once they have fulfilled their roles, walk off in their ostentatious costumes. False judges in their white wigs, fat prostitutes with provocative moles, shirtless boys in shorts, two young men tucked into the same pair of pants, two children and their parents in blue rabbit suits accompanied by a slight woman in a butterfly suit—the public greets the actors, offering reverence and congratulations, or chatting with them. The din grows, and the voices, ever louder, along with the clicks and flashes of the instant cameras, obscure the spectacle of the Apocalypse, which the public has all but forgotten.

Like a round and ripe orange, the sun begins its gradual descent into the celestial glass. Shadows fall across the Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Ay, guey, this already seems like it’s for real says a teenager with obsidian hair and a denim and sheepskin jacket. No one laughs. It had been an idle and joyful celebration, but the quickening onset of dusk with its long-fingered and persecuting shadows provokes a sense of malaise. The crowd, until then friendly and comfortably talkative, grows hostile. They exchange odd looks when they first notice the faces suddenly distant. Then comes a collective memory: the Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Almost in unison, their heads turn upward like sunflowers in search of a light, which—they discover—has mysteriously disappeared. Suspended on their stilts, the actors remove their masks and reveal their off-white faces, staring terrified at a sunless sky, dark clouds congregating. Like a single pane of glass, the silence is broken with a flash: a small vendor of antique clocks snaps a photograph of the family of blue rabbits for posterity. The rest understand: by an ill-fated upheaval of destiny, the spectacle is the true end of the world.

V. The Day Following the Origin

There was no newspaper on earth to report on the tragedy. Of that ominous afternoon on the esplanade (a final warning?), there remains no memory other than this. The useless, solitary recollection of something that never happened. It was a fact that spoke only of itself.

VI. The Day of the Animals

Nobody was there to warn them. Nobody let them out of the zoos or houses. There were no discussions (as may be obvious).

Perhaps the dogs were first, followed by the cats; infinite masses of birds; flocks of skinny ewes; herds of red deer and cows. They crossed tacit frontiers, both urban and rural, coming from mountain and dale. Colorful and chirping frogs invaded the highways, thousands of them, green and blue and red and yellow. The diversion was fleeting, for they succumbed almost immediately to the waning of oxygen. But for that single day, they were once again the true owners of the earth.

VII. Between Worlds

The ferocity of the rain began to fade, and with it went Marcial’s spirit. The days replete with silence, the cruel climate, the scarcity, the scarcity, more than anything the scarcity; the supplies both vegetable and human, the strangeness, the constant state of alert, the nightmarish insomnia that is being between worlds (which is how Marcial has baptized this new state of things) extinguished his will. Nothing is twice when it is between worlds. Whatever exists, exists (though even this sentence is impossible) once, and without so much as a flash, will soon disappear among patches of black or ruddy clouds. Marcial maintains that there may even be human figures that appear on the immediate horizon, only to be lost in a threatening fog of flames. At first Marcial attributes his improbable existence to the enigmatic nature of miracles—though he considers the possibility that fatigue has left him with no other explanation. But his discovery of the past few hours, or days, or years—another of the features of existing between worlds (the truth is that it cannot be called a feature if it is an attribute that doesn’t just change but fully disappears in the blink of an eye)—is the inexistence of time: sometimes Marcial wakes up as Marcialito, the seven-year-old boy who fashions virtue out of deficiency. He goes back to sleep, and when he opens his eyes again (though he isn’t sure whether he was actually sleeping when they were closed), the hair on his head and face has grown, and the rock upon which he believed he had submitted to sleep, or sleep had submitted to him, is no longer there (although, in truth, there is no there for it to be), as if each and every night someone was in charge of transporting either him or the world from one place to another . . . The discovery (without temporal attributes) provokes it: Will there be (will there be) more (more) like (like) him (me)?

As a result of his finding the photograph, Marcial’s senses seem to have sharpened. He perceives the scent of old ash, examines with new care and clarity the husks of the buildings around him, and hears a particular sound that was not there before. A weak but constant sound that begins to gather force in his mind. It overtakes all that he can hear.

With the photograph in his hand, he ventures forth, his earlier timidity gone, he walks assuredly, as if he knows where he is going. If the sound is coming from everywhere, he thinks, then everywhere is where I will walk.

VIII.

How many days or months or meters or miles have I walked? It is impossible to calculate. The territory was always and everywhere the same. But I concluded that no one ruin is like another. Everything was at once foreign and familiar to me. In my pocket, that photograph pulsed with an incessant force: I understood that it had become my heart. At first I thought that it had been given to me to decipher the foolishness of uncontrollable ambition. Indestructible. Also destructive. But no sooner did I have that ambitious thought than I abandoned it in favor of the song in my head. I asked myself where my mother could be, whether she’d also been able to withstand the poison, her lungs adapt to this solitary inclemency and the dearth of oxygen.

Faltering, hoping that the photograph would guide me to my own end, I looked at it for what I thought could be the final time. A family of rabbits. A family of smiling humans and rabbits. I leaned back upon a mossy rock, and the song returned to me more intense than before: an explosion accompanied by a sudden movement. The rock beneath my head floated up in the air, as light as a feather. It was croaking and croaking. It cracked open to reveal another rock, croaking and croaking as well. And I understood that this was not the end. That there is no end. And the rocks were not rocks but rather happy frogs, being continually born through their croaking mouths. Photograph in hand, I continued on my way toward the mystery of the blue rabbits, vestiges of history.