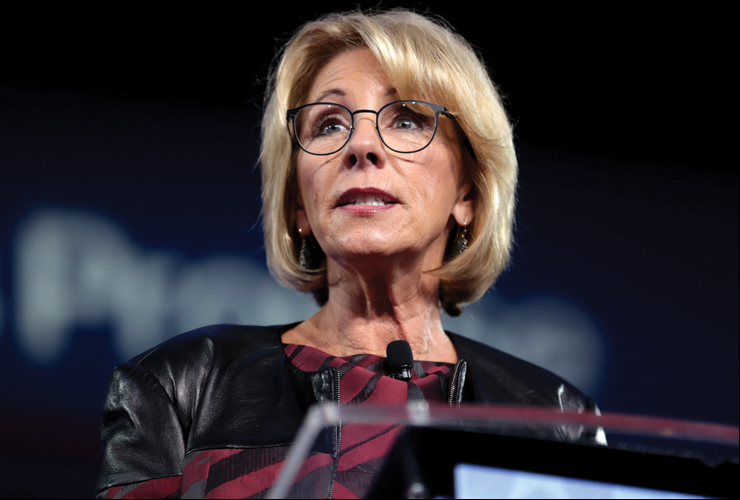

In September the Office of Civil Rights (OCR), under the direction of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, revoked the post-2011 Title IX guidance documents in their entirety and refrained from issuing more specifics until the completion of a potentially lengthy “notice and comment” rulemaking process. Activists hoping to preserve Obama-era regulations anxiously anticipated OCR’s announcement, and some have claimed that this action already makes campuses “less safe.” Those critical of Obama-era guidance celebrate the new regulatory environment as a victory for protecting the “rights of the accused” in campus adjudicatory processes. Despite the appearance of a dramatic turnaround, the impact of this shift in regulation, for better or worse, is mediated by the already crucial role of experts in Title IX implementation.

Selling their expertise as risk managers, legal entrepreneurs have been key players in designing implementation strategies for Title IX since 2011. By some estimates, colleges and universities have already spent millions of dollars for their services. The National Center for Higher Education Risk Management (NCHERM) has jumped into the forefront as the self-proclaimed “thought-leader” on Title IX by proffering its distinctive interpretations of OCR guidelines—all of which substantiate the role of experts and remove Title IX processes from pre-existing college disciplinary practices.

The threat of OCR enforcement displaced the goal of sexual equality with demands to protect institutions from liability and reputational risks.

These risk managers devised Title IX-specific compliance systems, in which judgments about what constitutes sexual misconduct are entrusted only to trained administrators, attorney investigators, and expert hearing panels. To allay concerns about federal sanctions, experts urged schools to broadly interpret the 2011 guidelines in terms of how they defined sexual assault, exploitation, or harassment and the responsibilities of all college personnel. These systems were marketed as the means for schools to become more responsive to victims’ needs, facilitate greater surveillance of discriminatory behaviors on campus, and allow for more efficient adjudication of complaints.

While this expansion of administrative authority has been justified as necessary to “take sexual violence seriously,” it rests on tenuous grounds when it comes into conflict with the due process rights afforded to all students, especially when authorizing punitive action against the accused. In reaching determinations about “responsibility” administrators become arbiters of students’ appropriate sexual behavior, and in some cases, make highly subjective interpretations about what constitutes consent.

In essence, the compliance business has turned sexual assault determinations into an administrative practice in which the protection of the rights of both the complainant and accused is entrusted to the judgment of experts. These practices are largely shrouded from public view by confidentiality rules, precluding faculty and students from scrutinizing the decision-making process governing investigation and adjudication. Yet a vigorous public debate has emerged even with limited knowledge about the successes and failures of these new systems. The ensuing controversy has only served to further ensconce the role of experts, who engage in the continuous and ongoing work of shoring up the legitimacy of their administrative apparatus.

While still claiming their commitment to taking sexual violence seriously, specialists have already begun retooling compliance systems in response to the changing liability environment. Even before September’s OCR notice, risk managers chastened Title IX administrators for ignoring an evermore-potent threat, the growing number of accused students filing cases in federal courts, where colleges are “losing case after case.” With the shifting political winds, these risk managers continue to be well situated to sell their services and claim their indispensability in an inconsistent and confusing regulatory regime.

Now that this administrative apparatus is deeply entrenched within institutions of higher education, new OCR guidance will be incorporated as it affects the risk of either federal sanctions or adverse outcomes in federal courts. Yet the controversies arising from the enforcement of Title IX threaten the autonomy of U.S. colleges and universities not only because they have deferred to experts, but also due to intense attacks from outside critics. These attacks are fueled by a powerful symbolic “crisis,” which distorts how we see the problem and stirs-up horror stories about an abusive system. This crisis has spurred a national conversation that shuts out commentary that isn’t victim-affirming (for either complainants or accused). This polarized dispute has put higher education on trial, its accusers casting it as dangerously out of control and in need of accountability. To get to the actual issues at stake, we need to look beyond this symbolic maelstrom and carefully examine the realities of Title IX implementation.

The sexual assault “crisis” came into full force by 2010, as student activists declared an epidemic on college campuses and employed some of the most divisive and simplifying mantras of anti-rape politics. These students called out a “broken culture” and demanded that administrators provide safe environments. In stories that recounted the particular vulnerabilities of a young woman entering college and leaving home for the first time, public attention was drawn to a trope of the idealized victim and aroused sympathy through reference to her exceptionally promising future. The campus rapist was almost always cast as a fraternity member or athlete. The constant references to repeat offenders fueled the message that the only way to address the problem was to impose severe punishment and expulsion.

The symbolic language of victim-centered politics bolstered a crime control response.

In the midst of this outcry the OCR issued the April 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter, in which the Assistant Secretary writes: “The sexual harassment of students, including sexual violence, interferes with students’ rights to receive an education free from discrimination and, in the case of sexual violence, is a crime.” Contrary to the propaganda of opponents, this statement did not imply that schools should be empowered to “prosecute” crimes; rather, it is a proscription about the reach of civil rights protections. By both placing obligations on educational institutions and informing students of their civil rights, this guidance letter ostensibly breaks new ground by creating a civil remedy in response to any and all forms of sexual misconduct.

In a move to promote “transparency,” the OCR released the names of all the colleges and universities under investigation, creating an aggressive regulatory climate. Unlike previous OCR efforts to concretize the meaning of racial balance in school desegregation or the suitable measures of equal funding in school programs, the Obama-era OCR directives where directed at a more ambiguous goal—creating an environment in which “all students feel safe in school.”

The threat of OCR enforcement produced a swift and troubling response. Many institutions of higher education across the United States sought out specialists who claimed to offer expertise on the correct interpretation of guidance letters and the necessary steps to avoid sanctions. Under their direction, institutions hastily adopted a fully prescribed Title IX disciplinary regime that imposed broad authority to set norms and punish behavior in campus communities. “In the name of victims,” we saw a rapid growth of regulations on college and university campuses that had the unintended consequence of displacing the actual goal of sexual equality with the competing demands for institutional safety from liability and reputational risks.

This diffusion of Title IX reform remained mostly unchallenged within academic institutions, as administrators have been successful in framing these specific policies, in their entirety and with little variation, as mandated for compliance with federal law and in service of the greater good of student safety. These motivating factors are particularly impactful given the fit between these compliance mechanisms and managerial structures already in place in institutions of higher education. With the growth of managerialism in corporations and now universities, risk driven efforts to promote campuses as “safe spaces” created governing logics compatible with the kind of “best practices” approach required by the federal government.

Compliance specialists strongly counseled university clients to standardize workplace regulations and increase monitoring of employee behavior.

Experts described compliance as part of a cultural shift that requires all employees to gain cognizance of their responsibility to reduce risk and assure student safety. The challenges of compliance, according to consultants, stem from the complacency of university personnel who assume that their professional status exempts them from regulatory enforcement. By describing the university as a resistant regulatory environment, compliance specialists strongly counseled their university clients to use this opportunity to standardize workplace regulations and generally increase monitoring of employee behavior. As Title IX compliance became widely understood as a practice of safety regulations, competing rights claims from faculty were dismissed as contrary to the promotion of safe campuses. Once framed in these terms and the all-encompassing logic of minimizing risk, almost anything and everything related to sex is viewed as a liability issue.

As a consequence, this regulatory framework justifies policies (such as mandatory reporting, investigatory and fact-finding methods of resolution, displacing community standards with expert judgments, and proceeding without victim cooperation) that not only diverge from the culture of academic life, but also actively undermine that culture, especially the environment of free discourse sustaining the unconstrained pursuit of knowledge. In a major report on Title IX procedures in higher education, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) raised concerns about threats to governance and academic freedom. While faculty largely remained acquiescent as major changes in disciplinary processes were introduced by risk managers, the AAUP report enumerates the cost of delegating the vital function of setting academic community norms to outside “experts.”

The swift adoption of compliance systems bolsters institutional power and potentially gives college and university administrators broad leeway to claim they are acting in the best interest of campus safety. But at the same time, a powerful symbolic “crisis” provoked legislative action and brought higher education more deeply into a culture war.

In his classic scholarship on symbolic politics, political scientist Murray Edelman demonstrated that when leaders point to recurring crises, they construct a reality that is disconnected from facts and serves to polarize audiences, evoke enemies, simplify the problem, and then overestimate the capacity of government to solve it. These political cues are especially potent when referencing both “sex” and “violence,” symbols that conjure up underlying anxieties and uncertainties endemic to modern life, rallying our sympathies for victims.

The rallying call came from campus rape survivors who evoked these classic motifs of symbolic politics in their social media campaigns. Their story was powerfully told in the documentary film, The Hunting Ground, which captured their sense of betrayal by highlighting cases where reports of sexual assault were ignored or handled incompetently by unsympathetic administrators. Media savvy groups, such as End Rape on Campus (EROC), established a nationwide alliance of anti-rape activists and then successfully sought out allies in power. With the resonance of their message on a national stage their cause was ripe for appropriation by politicians, university administrators, and federal regulators, who claimed to identify with victims and often made them the rhetorical object of their pleas for reforms. On behalf of those who are most commonly referred to as, “the activists,” politicians appropriated their rage, admired their bravery, and celebrated their courage.

As Title IX compliance became understood as a practice of safety regulations, competing rights claims from faculty were dismissed.

Ultimately, it was impossible for student activists to distinguish their cause from other campaigns designed to further the adoption of victim-centered policies. Such movements have arisen literally “in the name of victims,” and include Megan and Jessica Laws and Amber Alerts. Akin to other single-issue political crises that political leaders capitalize on—from the war against drugs to the threat of child abduction—this symbolic message about “rape on campus” created opportunities for leaders to claim responsibility for and success in addressing a social problem.

And similar to these other movements, the symbolic language of victim-centered politics bolstered a crime control response. As Jonathan Simon argues in Governing Through Crime, this language evokes a vision of the needs of citizens “framed by the problem of crime.” These rhetorical motifs, as applied to campus rape, focused on the serial rapist as super-predator.

Such posturing was seen most recently in The Campus Accountability and Safety Act (CASA) hearings, in which the threat of the campus predator was repeatedly evoked by citing unreliable research claiming that serial rapists are the greatest threat on campuses and that “more than 90 percent of campus rapes are committed by a relatively small percentage of college men — possibly as few as 4 percent — who rape repeatedly, averaging six victims each.”

One of the most consequential effects of tropes of crime control is that it casts all forms of sexual misconduct (across a wide spectrum ranging from a sexist comment to forcible rape) as necessitating punitive action. CASA included a hodgepodge of provisions, all of which solidified the role of law enforcement in campus proceedings. Unless colleges and universities established a Memorandum of Understanding with all local criminal justice agencies they would be subject to fines. The bill would require every college to have a confidential advisor on staff whose job would be to protect students from coercion to report and violations of their privacy, but incongruously, this advisor would also fulfill an ambiguous criminal justice function of investigating and reporting to law enforcement.

The congressional call to strengthen law enforcement’s role in collaboration with institutions of higher education fit their own “tough on crime” agenda, but it was also a direct response to critics who questioned whether campuses should be in the business of trying rape cases. The measures mandated in CASA seek to legitimize the campus adjudication process by turning it into a criminal enforcement apparatus.

These supposedly pro-victim, crime control proponents are pushing in the wrong direction. In effect, legislators are promoting more surveillance and punitive action. They also play into the hands of opponents of Obama-era regulation who claim that Title IX hearings have usurped the role of criminal courts in prosecuting rape and replaced them with “kangaroo courts.”

This kind of opposition is voiced by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), which portrays itself as a defender of freedom of speech and due process rights. They claim that the accused are “sentenced (emphasis added) with no regard for fairness or consistency,” and as a consequence, “a generation of students is being taught the wrong lessons about justice—and facing the ruinous consequences for their personal, academic, and professional lives.” These opponents raise the specter of colleges and universities on a rampage, as in a Heritage Foundation report that claims they use “their internal disciplinary processes . . . with shockingly little regard for the due process rights of students who stand accused of one of society’s most heinous offenses.”

The highly bureaucratized, overly process-oriented systems of Title IX administration bear little resemblance to their phantom characterizations as kangaroo courts. Nonetheless the objectives of these attacks are clear—to take away from universities the authority to adjudicate complaints in civil rights processes and force students to take “real rape” cases to criminal courts where they believe such matters belong.

Neither side fully recognizes that the criminal justice process offers a wholly inadequate response to acquaintance rape. The criminal justice system has an extremely high attrition rate in processing sexual assault cases—at all levels of the process—reporting, charging, prosecution, and conviction. Only a very small percentage of sexual assault cases end with sentencing a perpetrator to prison. While this is true for even the easiest cases to prosecute—where the defendant is unknown to the accuser and there is evidence of the use of physical force—the attrition rate is even higher for acquaintance rape. Many jurisdictions have adopted criminal statutes that allow for prosecution in situations of non-consent without proof of force, but problems persist, including collecting reliable evidence and the perception of prosecutors that juries will not convict. Indeed, even if charges are brought and a well-evidenced case can be established, the outcome is most often a plea bargained sentence of less than six months.

Fundamentally, Title IX is, and should be, upheld through civil action.

Although a full picture of Title IX case characteristics is currently unknown, it is likely that few sexual misconduct cases considered in campus hearings would ever lead to sexual assault convictions in a criminal court. But nothing stops complainants from bringing their case to the police. In fact, colleges and universities are expressly prohibited from discouraging students from pursuing this option. If complainants have a viable criminal case, the slow wheels of justice can proceed in the courts while their complaint is addressed on campus.

Fundamentally, Title IX is, and should be, upheld through civil action. Most complaints involve forms of inappropriate behavior and sexual harassment that cause harm but do not meet the definition of sexual assault in criminal statutes. Civil remedies ensure colleges and universities can respond immediately and effectively to impactful incidents of sex discrimination that can interfere with and negatively affect students’ educational opportunities and for which students need immediate and effective plans for remedial action.

One of the most notable aspects of September’s OCR announcement was that schools in their Title IX adjudications may now adopt either the Obama-era “preponderance of the evidence” standard or the “clear and convincing evidence” standard. Even though the preponderance of evidence is typically applied in civil rights cases, opponents of Obama-era regulations have vehemently claimed it infringes on the due process rights of the accused. This claim has symbolic resonance in a crime control culture, in which it seems to make sense to have campus disciplinary processes mimic the criminal justice system. Despite the contentious public discussion, if implemented, rather minor modifications in the instructions given to administrators about how to weigh evidence might have little impact on the outcome of cases. However, schools will be attuned to the potential liability issues. In a footnote, the OCR warns that if schools use a different standard for Title IX than other disciplinary hearings, it might indicate bias toward the accused.

Other, more far-reaching changes are hinted at by the OCR. These suggestions include a possible response to the alarms sounded about kangaroo courts by signaling that the 2011 letter “forbade schools from relying on investigations of criminal conduct by law-enforcement authorities…, forcing schools to establish policing and judicial systems (emphasis added).” This may indicate a move toward a responsiveness to regulations that intertwine campus disciplinary processes with local law enforcement.

In actuality, the current environment of legal liability may, at least temporarily, forestall Secretary DeVos’s efforts to bring Title IX enforcement under a new political regime.

The effect of the war over Title IX will be a deeper entrenchment of a risk management regime in all aspects of student discipline.

Many colleges and universities have been quick to confirm that the rescission of guidelines will not lessen their commitment to enforcing Title IX or to their responsibility to address sexual assault. While optimistically this reassurance reflects a post-2011 resoluteness to “do the right thing” in regard to sexual assault cases, realistically, institutions are hemmed into a steady course. The interim measures merely increase uncertainty about the possibility of federal sanctions and the outcome of pending litigation of the due process issues in federal courts. As these cases percolate across jurisdictions, decisions are likely to provide complex and contradictory interpretations of what constitutes fair and equitable procedures.

If colleges and universities change direction now, they will create liability, as the foremost risk specialist on Title IX ominously warns: “Schools must consider, for example, whether raising the standard of proof—if that is even permissible under law—would trigger lawsuits by every student disciplined under prior, lower standards? Plaintiff’s lawyers are waiting with baited breath for any school to make that move.” This startling advice reveals that higher education is “locked-in” by the proscriptions of risk management. The avoidance strategy has come full circle—institutions that followed managers’ advice to speedily adopt new procedures to avoid federal sanctions must now fear that any change in those procedures will increase their exposure to the risk of lawsuits brought by Title IX respondents.

The long-term, most impactful effect of the war over Title IX will be a deeper entrenchment of a risk management regime in all aspects of student discipline. Yet this public spectacle has also placed higher education in the cross-hairs of those who claim it has become an “echo chamber of political correctness and homogeneous thought.” While the ostensive battle lines pit “safe campuses” against “due process,” the attack on Obama-era guidance is part of a larger effort to thwart the progress of civil rights by casting it as a threat to individual freedoms. This can be seen, for example, in propaganda that claims enforcing Title IX silences a “Million Voices”

The controversy has also promoted a backlash against feminist-inspired cultural change. Critics of Obama-era enforcement strategies allude to feminist forces on campus declaring war against men. As argued here, the apparatus designed by risk managers and the efforts of legislators to add new mandates is largely driven by a crime control agenda and a strain of new managerialism, much of which runs counter to both feminist principles and longstanding governance norms of academic institutions. In fact, professors of gender studies have taken the lead in calling for compliance strategies more in line with the complexity of gender issues and reflective of academic knowledge about sexual assault.

Lastly, the public debate has also distracted attention from serious difficulties that arise in implementing Title IX. By placing a singular focus on sex discrimination it often fails to foster greater awareness about intersecting forms of discrimination and the role of class in access to education. At a time when university and college campuses need to reconcile their promotion of diversity with the hardships experienced by first generation students, the singularity of Title IX policies distracts from fully considering how gender, race, disability, immigration status, and socio-economic background impact students’ abilities to take advantage of their education. Most importantly, a clearer sense of purpose would emerge with a shift away from punitive solutions to a greater emphasis on prevention and direct support for survivors. All along, the feminist-inspired group, Know Your Title IX, set this example by drawing attention to what students want and need to protect their rights.

This “crisis” of sexual assault on campuses may bring about some positive results, most likely through increased awareness, promoting education about gender equality, and gradual culture change. There are certainly hard lessons to be learned about the deference to opportunistic actors and the new cadre of compliance specialists who claimed to know the “law” and how to “fix” campus culture. Colleges and universities have a duty to address sexual violence on campuses and beyond. Yet they also must defend themselves from forces that threaten their autonomy as academic communities.