By the end of the 1990s, policymakers and police were celebrating the great American crime decline. Rates of murder, robbery, and rape had fallen across cities and suburbs, among rich and poor.

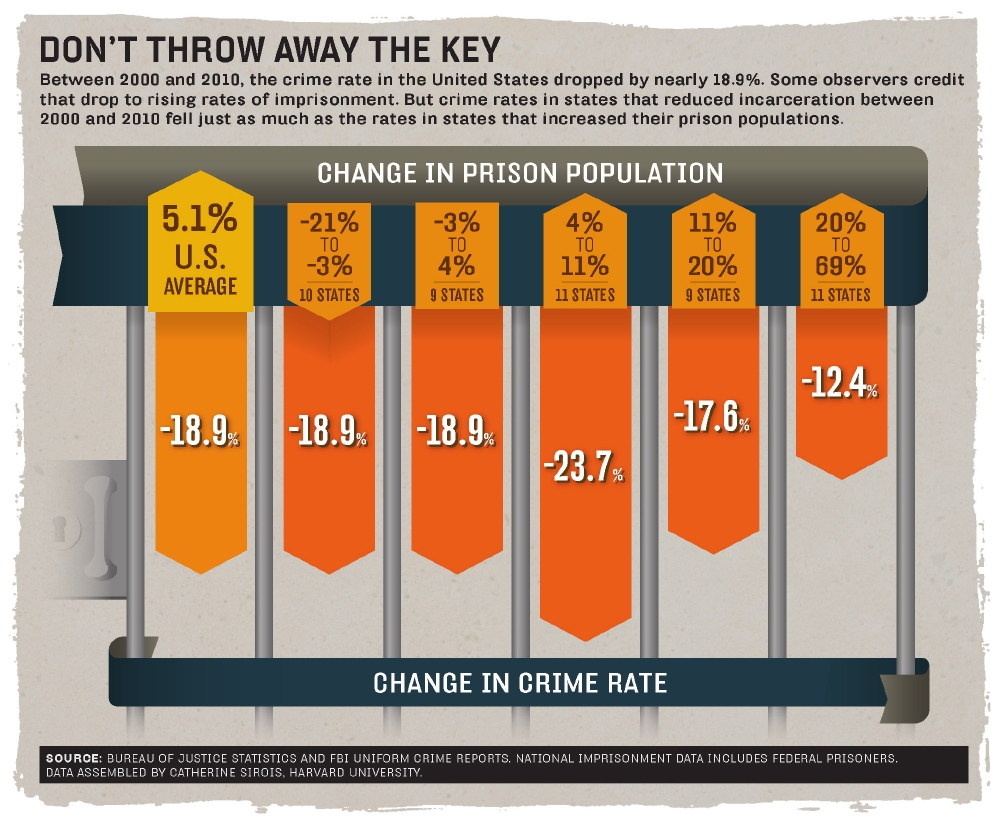

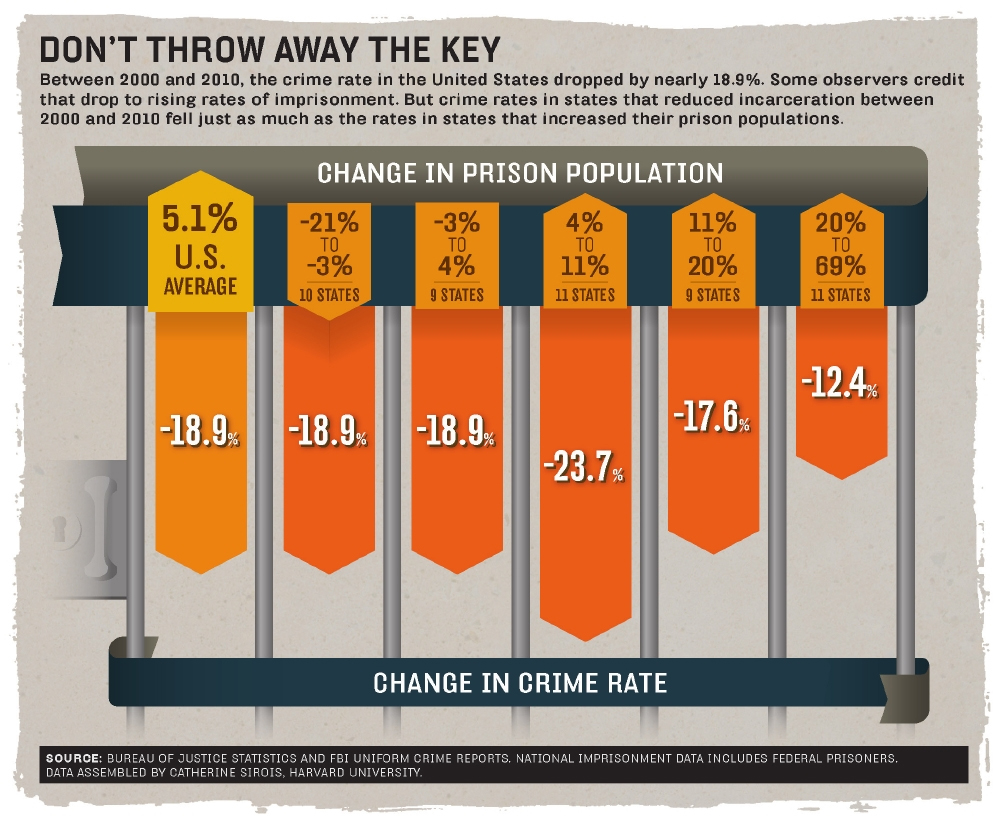

Less appreciated perhaps is the continuing decline in crime in the 2000s. In every state fewer incidences of serious violence and property crime were reported to police in 2010 than in 2000. The murder rate is now the lowest it has been since the early 1960s.

Research on the 1990s traces the crime drop to better policing; to a subsiding crack trade, which, at its height in the late 1980s, unleashed a wave of murderous violence; and to increasing prison populations.

However, some researchers find the apparently large effect of imprisonment controversial. Driven by tough-on-crime policy and intensified drug enforcement, prison populations grew unchecked from the early 1970s until the last decade, but crime rates fluctuated without any clear trend. By the early 2000s incarceration rates had grown to extraordinary levels in poor communities. Whole generations of young, mostly minority and poorly educated men were being locked up, leading to the United States’s current status as the world’s largest jailer, in both absolute and relative terms.

Prisons may have reduced crime a little in the short run, but at the current scale the negative effects of incarceration are likely to outweigh the positive. Commonplace incarceration among poor young men fuels cynicism about the legal system, destabilizes families, and reduces economic opportunities.

Over the last few years, the rate of prison population growth in the states finally began to slow. (The growth in federal prisons has continued unabated.) As the political salience of crime declined and the cost of prisons ballooned, policymakers and the courts turned to alternatives to incarceration.

Twelve states reduced imprisonment in the last decade. These states diverted more drug offenders to probation and community programs, and parolees were less likely to return to the penitentiary.

All the states that reduced imprisonment also recorded reductions in crime. For instance, between 2000 and 2010, New York cut imprisonment by about a fifth, and the crime rate fell by about 25 percent.

States that raised their imprisonment rates averaged similar reductions in crime, though the declines show a lot of variation. Where prisons grew by more than 20 percent, crime fell by a little less than the national average. And in some places—such as Maine, Arkansas, and West Virginia—crime barely fell at all.

It seems clear, then, that ever-increasing rates of incarceration are not necessary to reduce crime. Although it’s difficult to say precisely how much the growing scale of punishment reduced crime in the 1990s, the crime decline has been sustained even as imprisonment fell in many states through the 2000s.

These data are good news for governors who want to cut prison budgets. But cuts alone may not work. Policymakers should study cases such as New York and New Jersey. These states cut imprisonment while building new strategies for sentencing, parole and after-prison programs.

The era of mass incarceration is not over, but there are signs of reversal. Given the social costs of incarceration—concentrated in poor neighborhoods—these are heartening trends. The last decade shows that public safety can flourish, even as punishment is curtailed.