Retrieving Realism

Hubert Dreyfus and Charles Taylor

Harvard University Press, $39.95 (cloth)

In a hut in southern Germany and an apartment in New York City, about ninety years ago, two philosophers tried to sort out a family of ancient problems concerning experience, knowledge, and our place in the world. Working independently, they developed a similar idea and used it as a launching pad for more.

The way to make progress on those problems, they thought, is to treat our practical engagement with the environment as primary. “In our dealings we come across equipment for writing, sewing, working, transportation, measurement.” We encounter ordinary objects “as things of doing, suffering, contact, possession and use.” When we engage with such things, they are “not thereby objects for knowing the ‘world’ theoretically; they are simply what gets used, what gets produced, and so on.” “They are things had before they are things cognized.” The move to understand things theoretically only comes about when there is some interruption or “deficiency” in our ordinary dealings. A common error in philosophy, however, has been a kind of “intellectualism,” treating all our contact with the world in terms of concepts and representations, assuming that “knowledge is the only mode of experience that grasps things.” The irony is that such intellectualism makes knowledge itself impossible to understand. If we forget that knowledge is derivative from more basic kinds of engagement with the world, we end up “making knowledge, conceived as ubiquitous, itself inexplicable.”

These are central themes also in Hubert Dreyfus and Charles Taylor’s new book, Retrieving Realism. As Dreyfus and Taylor see it, philosophical work in the modern period (in the philosopher’s sense of “modern,” which starts around 1600) has been plagued by a mediational view of how we relate to the world. “Only through” intermediaries can we have contact with things outside us. A few hundred years ago the mediators were supposed to be image-like sensations or ideas. Now they are often sentences, or internal representations of the kind envisaged in artificial intelligence and cognitive science. The mediational approach, for Dreyfus and Taylor, is one that people adopt without entirely realizing it. Working within it, however, leads to many errors and misguided debates. It leads to a dualistic sorting of the world’s contents into mental and physical, and with this comes an acute problem of how the two sides could be related. But from the early twentieth century, a better view has slowly developed, according to Dreyfus and Taylor, especially through the work of Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. They show us how to have a theory of contact with the world without mediators, through a “reembedding of thought and knowledge in the bodily and social-cultural contexts in which it takes place.”

Compact and engaging, Retrieving Realism is more approachable than its weighty subject matter might predict. The book begins from an assertion of the “embedding” of thought and knowledge in its bodily and practical contexts, and then argues against a range of views that try to insist that our contact with the world must somehow run through representations, language, or concepts. Instead, our basic contact with the world involves a kind of “absorbed coping.” The authors are not entirely hostile to the idea of representation of the world in our minds and in language, but those phenomena are secondary. Recognizing this, for Dreyfus and Taylor, enables us to recover from the morass of mediationism the idea that we live in, and can know about, a world that exists independently of us. That is the realism that is being “retrieved.”

The point that not everything we do makes use of theories and concepts might seem obvious—clearly we also eat and drink and walk on things. But Dreyfus and Taylor think that philosophy constantly invents new ways to falsely intellectualize our relationship to things that we do. Philosophy itself does not subside once we see these issues clearly; philosophy has tasks beyond merely diagnosing errors. We have to work out how to negotiate differences between cultures and between different methods of knowing the world. This work will go better when those differences are understood against a common background of dealing with the world that we all, as humans, engage in.

The early twentieth century was indeed a time when the philosophical landscape shifted, but Dreyfus and Taylor give a one-sided account of the events of this period. The two figures at work in my opening vignette were Heidegger, in the hut, and John Dewey, in New York. Heidegger’s Being and Time was published in 1927. A few years earlier, Dewey published Experience and Nature, revising it in 1929. This was not Dewey’s first book, as in Heidegger’s case, but the fourteenth of (too) many, containing ideas that had developed from Dewey’s first years as an “idealist” philosopher, through the classic debates over pragmatism in the first years of the new century, to this mature position.

The pragmatist tradition wanted to embed thought and knowledge in a broader context of human action and social life. That idea is vague, and the way it was done was sometimes simplistic. What is important here is how it was done, eventually, in the best work by Dewey. The fragments of philosophy quoted in my first paragraph are a mix from early sections of Experience and Nature and Being and Time, chosen so both writers would accept them. (On the Dewey side, I have included phrasings from both the 1925 and 1929 editions). Philosophers tend to treat experience as a veil or screen, Dewey says, that shuts us off from nature. This is an error. Ordinary experience involves a to-and-fro of sensing and acting in which the valuable features of objects are as present as their “factual” ones. The way to understand knowledge and inquiry is to see them arising from, and in service of, more basic kinds of engagement with the world.

Philosophy constantly invents new ways to intellectualize our relationship to things we do.

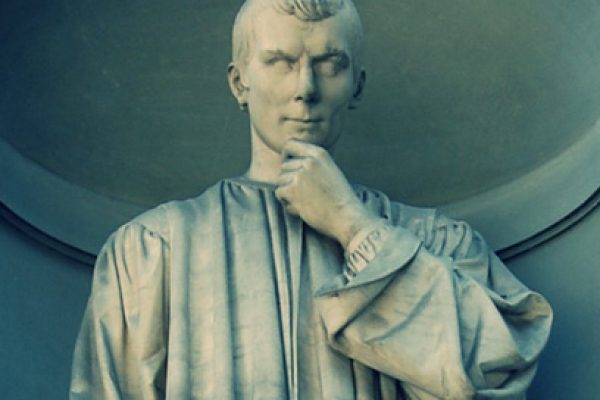

In Retrieving Realism, Heidegger gets the credit for these moves and Dewey does not figure in the story at all. It is sad to see such an innovator—also a dedicated communicator, far-sighted and progressive in political affairs—left out entirely, while Heidegger—who joined the Nazi party, encouraged students to wear SA or SS uniforms as he led them marching off to “Scholarship Camp,” and wrote in a way that sank a large sector of European philosophy into unprecedented incomprehensibility—is praised for pretty straightforward ideas that both of them defended.

Is this just a matter of fairness? If so, perhaps there is not much of a criticism to make. All philosophers have their simplified historical stories; this is part of how we do things. We tell “tales of the mighty dead,” as Robert Brandom puts it, charting what we see as good paths and bad ones. Dreyfus and Taylor are inspired by Heidegger; I am inspired by others. If the project on the table were serious history of philosophy, Dewey would be important and the relations between his ideas and Heidegger’s would deserve a close look. Dewey and Heidegger were influenced by different people—Dewey by William James and Darwin, and also by the nineteenth-century idealist philosophies of Hegel and his American admirers. Heidegger, on the other hand, trained in theology and then worked intensively with Edmund Husserl, the main figure in the early development of “phenomenology” as a philosophical method. Phenomenology is the close study of conscious thought, especially the way it is directed on objects, from a first-person point of view.

Everyone wants their favorite people included in a tale of progress, and my people differ from theirs. Given that the historical details are not the main topic of Retrieving Realism, should I just let them tell their story? The issue is not just historical fairness, though. Following a different historical path, in this case, also takes us to a better philosophical view.

Let’s now consider realism. The problem is traditionally posed like this: Does it make sense to think we inhabit a world that exists and has its structure independently of what anyone might think? The initial answer seems to be yes, but a problem that arises within any mediational view, in Dreyfus and Taylor’s sense, is how we can have access to such a world through our mental mediators. The realm of the mediators can also come to seem self-sufficient, so they are no longer mediators, but all we have.

Dreyfus and Taylor think this problem is best overcome by denying the mediational picture. Contact with the world is not a matter of peering through a veil. Think of walking the streets. As you walk you affect what you sense next. There is continual feedback as you adjust your acts according to what you sense, and produce acts that maintain the right sensory flow. Perception is not an internal registration of what is outside but rather an ongoing form of interaction that involves your senses, brain, body, actions, and environment. For Dreyfus and Taylor, once we realize there is no fundamental problem of access to and contact with the world, we are in a position to assess the distinctive kinds of contact we can derive from theorizing, both in informal contexts and in science.

Let us accept that and take another step. We sense and act and sense and act, as they say, and these actions also have effects on things. It is not just we who adapt as a result of what we encounter; the world is changed as a result of our actions. Dewey saw this as the key to resolving some old and misguided debates in philosophy. There is a tendency to seek a view in which one side calls the shots—either the thinking subject or the world encountered. This tendency shows up in realist philosophies that emphasize the inflexible demands the world can make on us, the “Coming, ready or not!” side of experience. It shows up also in idealist philosophies that emphasize the spontaneous activity of human agents, their imposition of will on the world. Dewey himself was brought up on these choices, and on the idealist answer to them (choose the active subject!). Eventually he saw a way to get over them.

Experience is a to-and-fro of sensing and acting, and those actions transform the environment. The act of building gives rise to new physical things—buildings—that shape our lives. The role of intelligence, for Dewey, lies in its taking the world down some paths rather than others. Some outcomes, some ways the world can be organized, only arise through actions that are guided by intelligence. The fragment of truth in idealist philosophies is the recognition that the mind is a genuine factor in the world’s development. The error is to think this happens not through action but through “some occult internal operation.”

If we accept this picture, is it the victory—the retrieval—of realism? Dewey himself did not see it that way. He thought both sides had erred too much; idealists in making mysterious the effect of thought on the world, realists in talking as if the world were “independent” of the mind. I think the realist side has prevailed, but the label does not matter much. The picture that results is one in which we live in a structured world and are part of the world’s structure. Our actions shape events, in a constrained manner. The effects of action, and hence of the thoughts behind them, are dependent on time, on a before-and-after. The opposition between the world as found and the world as made is resolved by this reference to time; we find the world in one state and leave it in another.

I see this treatment of realism and idealism as one of Dewey’s central achievements. In many discussions since his day, though, a form of the old error has been restored. Rather than resolving things through action and temporality, philosophers have fallen into a sort of blurry compromise. The world we live in, they say, is partly dependent on our categories and point of view, but not in a way that depends on action and physical transformation—in some other manner. Even Dreyfus and Taylor, with their focus on retrieving realism, end up in this territory. They claim that the world a person experiences is a “co-production” of their physical environment and the nature of their body. This co-production is not a matter of cause and effect, they say, but something subtler. It comes from the fact that “the terms in which we describe our experience . . . make sense only against the background of our kind of embodiment.”

These are surprising passages, given what their other pages say. What does it matter if some terms we use only make sense to a person with a certain kind of body? Dreyfus and Taylor move between saying that our experience is shaped by our bodily constitution and saying that our world is so shaped. This takes them away from the realism they want to retrieve. It is a common feature of work inspired by phenomenology. Phenomenology is all about our encounter with things; it is a first-person philosophy. In that context, there seems to be an ongoing temptation to soften the world experienced, to talk of a world for me and a world that might be different for you. This move away from realism is a particular problem for Dreyfus and Taylor, as they insist, not many pages later, on the independence from us of the world that is known. How does my world, the co-produced one, relate to the independent one? (I suspect this is one of the few places in the book where its dual authorship causes a problem.)

The transformation of environments through action, which Dewey uses to resolve these issues, is a third-person phenomenon. Looking on, we can see the world before and after this person acted, can see what difference they made. Some people might be made uneasy by this appeal to an external perspective. Another reason people might resist has to do with the feel of Dewey’s discussions in this area. His work can give a suspiciously strong sense of order and directionality. Someone influenced by Heidegger might instead emphasize the openness, the indefiniteness of what might be brought about. Who knows what we will do?

Though it might seem that Dewey’s philosophical innovation is dependent on his progressivist outlook, that is not so. The actions people choose and hence their effects on the world are indeed diverse, might go in a multitude of directions, might head toward less rather than more stability. But this is still the channel, the only route, by which human agency co-produces the world.

Given all that I have said, why is Dewey absent from Dreyfus and Taylor’s picture? His name appears just once in the book, in a quote from Richard Rorty. In 1979 Rorty published Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, a book with three heroes: Dewey, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein. If you read or quote Rorty, you will quickly run into Dewey. You will run into his name, anyway—there are some interpretive ironies here. Rorty praised Dewey to the skies, but as he did, he transformed Dewey into Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein (in his later period) thought that philosophical theorizing was a waste of energy. A clear-eyed inspection of ordinary social life removes any need for a theory of the sort philosophers want to give. Wittgenstein’s goal was to develop an anti-theory, an antidote to philosophy, a getting-over of the whole business. Rorty believed those things, too—in an alarmingly perfect image, he compared epistemology to a “collapsed circus tent” under which people are still thrashing about. Dewey did not believe those things; he saw a need for philosophical theories and wrote up a quite complicated one in Experience and Nature.

Why, then, did Rorty put Dewey in such a central place? I think it is partly because Rorty found Wittgenstein such an inappropriate model in other ways. Dewey was a great American progressive, a humanistic liberal, a founding member of the NAACP and supporter of the ACLU. He was also a great advocate of conversation and exchange. Wittgenstein, on the other hand, was a misanthrope, inclined to mysticism, who scorned democratic progressive ideas. I think Rorty was philosophically quite close to Wittgenstein, but politically so much closer to Dewey that he massaged Dewey into an anti-theorist like himself. In any case, perhaps Dreyfus and Taylor thought that by dealing with Rorty—which they do well—they had dealt also with Dewey. That is not so, as I have argued. There is another interpretive irony here. Dreyfus and Taylor do something like the opposite of what Rorty did: they try to turn Wittgenstein into Dewey—into someone who does want to give philosophical theories but thinks philosophy needs to recognize the social and cultural context in which language operates. Wrangling the mighty dead!

I don’t want to suggest, through this assertion of Dewey’s place in the story, that he had all the answers. Far from it, and I will look in a moment at an area he handled quite badly. In explaining his larger neglect in this part of philosophy, I am also mindful of other deficiencies. Dewey’s writing has an exhausting earnestness, which contrasts with the dark edginess, the anything-can-happen feel of Heidegger’s. If someone sees you reading Heidegger on a train, they might think you would be an interesting person to have sex with. If they see you reading Dewey, there is a risk they will think you would be an excellent person to serve on a committee.

Some discussions of Rorty in Retrieving Realism give a clue as to why Dreyfus and Taylor do not want anything to do with the pragmatist tradition. They associate pragmatism with a wholesale denial of the idea that language and thought can represent the world.

Suppose we accept that thought and reasoning are embedded in practical attempts to cope with our environment. Do our minds do this by creating simulacra, images, or other representations of the objects and situations we have to deal with? Dreyfus and Taylor highlight the errors of theories of human contact with the world based on representation, but they are not opposed to the idea of representation itself. They are against the idea that our contact with the world goes exclusively via representations. There is some risk of setting up a straw man opponent here. Is there anyone (after Bishop Berkeley) who thinks we only have contact with something beyond ourselves by means of representations? Words such as “contact” and “grasp,” which Dreyfus and Taylor use, cause problems, too. Everyone agrees we handle and bump into things—that is contact. What Dreyfus and Taylor want to do is introduce a broad sense of the word “knowledge,” which includes things such as know-how, and argue that a great deal of knowledge in this sense is not representation-based.

Dreyfus and Taylor put a lot of stock in arguments from phenomenology, but these arguments are weak. How things seem to us does not count for much in this case. They also think recent science helps them and supports a view that gives a rather limited role to representation. But here they cherry-pick, quoting a few fragments from work in neuroscience and psychology that suit their case. If the science is relevant at all, then cherry-picking is not enough.

The idea of internal representation remains extremely popular in psychology and neuroscience. Perhaps that is a mistake, but we at least need to consider the whole domain of what humans and other animals do. There is moment-to-moment coping with objects around us, which Dreyfus and Taylor emphasize, and there is also memory.

Memory, which is rather neglected in current philosophy, may support a very representation-heavy view of the mind. Consider a form of memory seen in many other animals as well as us: spatial memories used in navigation. In 1948 the psychologist E. C. Tolman published “Cognitive Maps in Rats and Men.” He argued that spatial skills shown by laboratory rats supported the idea that they build and use internal maps of their environment. Many philosophers influenced by people such as Wittgenstein would say this is absurd. Inner maps? Any map needs a reader. Are there inner rats and inner men to read them?

The internal map idea has always been a bit puzzling, but the evidence for this approach has become strong. In the 1970s John O’Keefe and his collaborators gave the first neuroscientific underpinnings to Tolman’s hypothesis, discovering “place cells” in the rat hippocampus that fire when the animal is in a particular location, regardless of other conditions. Further work on this system and how it helps rats navigate led to a 2014 Nobel Prize for O’Keefe, along with May-Britt and Edvard Moser. (During the time I was writing this review, an article came out of Hugo Spiers’s lab in London showing that, during sleep, rats activate place cells corresponding to a path they have never previously traveled, but at the end of which they have seen food. On waking, they choose that path.) On the behavioral side, Nicola Clayton, Anthony Dickinson, and others have found that some birds can remember where they have buried large numbers of individual food items and even retrieve these items in a way guided by their perishability. It may be that one very important way we cope with the world is by building and consulting internal map-like structures: that is how we, and rats, find our way home, whether it feels like it or not. A critic might object: “No, this is just a skill, it’s tacit knowledge.” Dreyfus and Taylor gesture toward such a view in a brief discussion of navigation. But then we should ask, as Tolman did: What about short cuts, and using novel paths? Rats, dogs, and various other animals can use them. Without a map, how can that be done?

Dreyfus and Taylor want to push a lot of cases onto the side of nonrepresentational coping, but they allow that representation has a role and are probably more willing than others in philosophy to let the chips fall where they may. The science here is at an early stage. To what extent do we deal with the world by mapping it internally, and to what extent do we do things differently?

Many philosophers have not done a good job with this issue. By the time of Dewey’s later work, he avoided talking about it. But he never, as far as I know, made reasonable concessions toward the possibility that internal representation of the world plays an important role in how we deal with it. Rorty kept arguing for the incoherence of internal representation, leading Dreyfus and Taylor to rightly accuse him of trying for wholesale arguments in an area where they are not to be had. Even some early pages of Retrieving Realism look questionable in the light of concessions made at the end. Dreyfus and Taylor begin by describing the approach they want to avoid like this: “The reality we seek to grasp is outside; the states whereby we seek to grasp it are inside.” That view is supposed to be a mistake, but inner mapping seems not very different, and that is where neuroscience may lead.

Retrieving Realism, with its adventurous combination of arguments and mixing of philosophical cultures, has unusual strengths and weaknesses. The section that won me over is a discussion of Rorty and Donald Davidson. Those philosophers saw themselves as overcoming all sorts of dogmas and misguided traditional pictures. Dreyfus and Taylor regard them as stuck within the mediational picture, with sentences playing the role in their philosophy that ideas played in older ones. Both Rorty and Davidson sternly insisted that there is “no way to get outside our beliefs and language,” while other philosophers foolishly think we can somehow step “outside our skins.” Dreyfus and Taylor use their treatment of perception to show that far from being truisms, these claims are just false.

On the downside, Dreyfus and Taylor are influenced enough by the contemporary philosopher John McDowell to agree with him that a theory of perception has to make sense of the role of “spontaneity.” What is spontaneity? It sounds like some sort of creative unprompted act. But spontaneity, in forming beliefs, turns out to be a matter of following where the evidence leads. Surely that sounds like the opposite of spontaneity, which has something to do with freedom? Well, we might give them this special use of the term . . . until they say that being “forced” to a conclusion by evidence and reason is the highest kind of freedom. Not to me. Following the evidence is a good idea, but freedom is something else.

The two books written in the hut and the apartment were immediate successes. When people found the first chapter of Experience and Nature confusing, Dewey rewrote it to make it clearer. Heidegger, in contrast, seemed as the years passed to become addicted to ever more extravagant aesthetic gestures. If obscurity is the accusation, Dewey was not blameless, but he was trying to retain, rather than willfully abandoning, the healthy vulnerability of clarity.