If we seek an explanation for the homophobia that caused Omar Mateen to murder forty-nine at Orlando’s Pulse gay nightclub in June, we should start not with the Islamic State, but rather with the two hundred anti-LGBT bills proposed by U.S. lawmakers in the past eight months alone. A longer view would take us back to 1992, when Pat Buchanan was lauded for his Republican National Convention keynote address blaming “the homosexual rights movement”—along with abortion, feminism, secularism, and environmentalism—for everything wrong with America. But if the gay movement continues to be punctuated by tragic setbacks, we must acknowledge that there has been a decisive change in the role of LGBT issues in American politics over the last twenty years. The culture wars have devolved mainly to the local and state levels—exemplified by North Carolina’s “bathroom bill”—while Supreme Court victories have changed the national landscape.

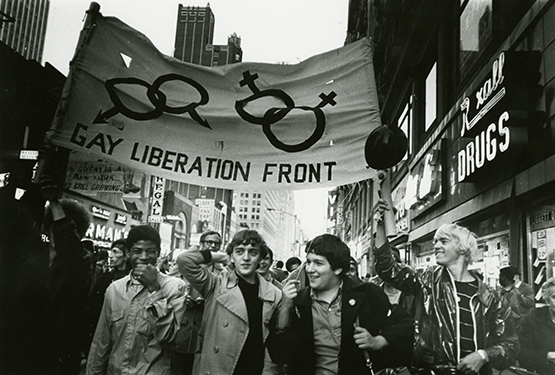

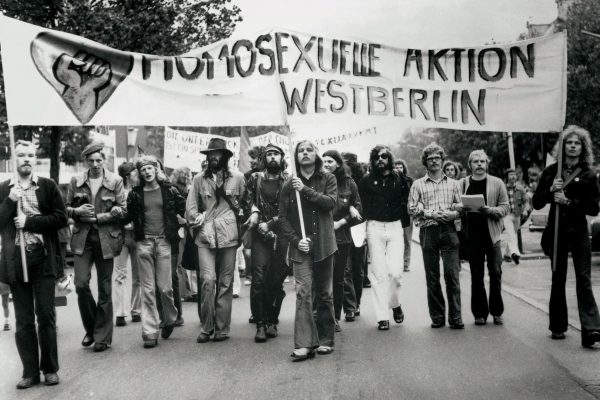

As a participant in multiple incarnations of the LGBT movement since 1969, I can say, advisedly, that the gay movement’s shift in the past decade—from calls for radical cultural change to the push for legislative adjustments—feels predictable, even inevitable. The impulse was always there. The gay movement, for lack of a more inclusive term, began in the early 1950s with homophile groups such as the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, which organized around issues of basic legal reform and protection from police harassment. Only much later, following the June 1969 Stonewall riots, did the gay movement become a specifically leftist one. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and related groups drew most of their members from the New Left. Fueled by the enormous energy of the Black Power movement, the antiwar movement, and Second Wave feminism (as well as sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll), this iteration of gay activism demanded not rights but wholesale cultural change. We were not interested in same-sex marriage: we were against all marriage as a patriarchal power structure. We were not interested in electing a gay man or lesbian to a city council seat: we wanted to upend foundational ideas about sex, gender, power, nationhood, and citizenship.

That these revolutionary ideas were mostly impossible to accomplish in any legal sense felt inconsequential to us. We wanted to change hearts and minds, not laws. It was the gay rights movement, which came later, that carefully picked and won legal battles at the local, state, and national levels. This was a matter of some tension, but what often goes overlooked is how the more radical movement made reformist successes possible.

A ground rule for political organizing and change is to always demand more than you expect to get. The idealistic goals of gay liberation were, by their nature, unattainable: stop the criminalization of all consensual sex, do away with confining gender roles, allow children and teens access to sexual information and the freedom to make their own sexual decisions, put an end to male privilege, abolish misogyny, disassemble the prison system, and explode the nuclear family. Many in gay liberation were also committed to ending the war in Vietnam, dismantling the military, ending capitalism, challenging imperialism, and fighting racism.

A more radical LGBT movement made today’s reformist successes possible.

But while many of gay liberation’s goals were out of reach—and those of economic and racial justice seem more remote now than ever—in many ways the movement achieved ideological success. New York’s GLF officially existed for only about two years, but by September 1969, more than three hundred groups emerged around the country, often on college campuses, calling themselves the Gay Liberation Front. Many were less radical than their namesake, instead focusing on rights or building local community. But, through these groups, gay liberation was transformed from a precise political ideology into a state of mind that sought—and achieved—cultural change. Today most sex-crime laws are gone, women have far more social and cultural freedom then they did in the 1960s and before, gender roles are far more open, transgender issues are taken seriously, it is relatively easy to come out, many secondary schools have gay-straight alliances, and recent polls show that many young people have fluid notions of sexual desire and gender.

• • •

Telling the complex history of the American struggle for LGBT, or queer, freedom is a fairly new endeavor, and three recent books demonstrate how far the writing of that history has come.

Lillian Faderman’s eight-hundred-page tapestry, The Gay Revolution, is a major contribution. But she sets a near-impossible task for herself: to keep the largest political scope while telling the story of a multifaceted, contentious movement in continual flux. Faderman seeks to show the connections between reformist homophile movements; radical gay liberation; reformist gay rights movements; radical, direct-action HIV/AIDS groups such as ACT UP; and rights-based, legal reform movements pursuing marriage equality and open military service. Readers must also grapple with the reality that, during many of the six decades Faderman covers, lesbians and gay men had very different needs and agendas and often did not get along (although this changed as the decades passed, especially after the first years of the AIDS epidemic). Likewise, bisexuals were often not accepted as part of this community, nor were non-cisgendered people, who were thought by many to be radically different and incompatible with a politics of respectability.

While the reformist/liberationist split was theoretically decisive during this time, in practice, as Faderman makes clear, many activists shifted between assimilationist and anti-establishment impulses. It is not that one type of political strategy or philosophy replaced the other, but rather that one or the other could be more strategically useful at a given time. In short, trying to find a cohesive narrative in these six decades is a nightmare. Whether it is a productive exercise remains an open question.

As a way out of this difficulty, Faderman frequently draws on personal vignettes and singular moments. This quick-sketch social history is not new to her. Faderman’s Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers (1991), a history of twentieth-century American lesbianism, aphoristically blends the social and historical. At their most successful, the episodes, written with succinct panache, are evocative in the way of montage. Take for instance her brief description of the Mattachine Society’s meteoric rise and fall. Founded in 1950 by the visionary Harry Hay, a member of the American Communist Party, the organization won the first major legal battle for gay rights when it successfully defended a founding member against the charge of public lewdness for soliciting an undercover cop. The trial won Mattachine attention and new members, which led the group to repudiate many of its founders’ radical-left politics. Faderman’s summary of this history is eloquent and economical:

The success of Harry Hay’s group led directly to its failure. Mattachine had been cast into prominence at the height of the government’s hunt for subversives. When no one was paying attention, it didn’t much matter that its founding members were politically as well as sexually subversive. But now, as the result of their victory, a spotlight was beating down on them.

Faderman emphasizes the important cultural changes wrought not by the legislative gains of the gay rights movement but rather by the revolutionary power of gay liberation. She notes that when Vice-President Joe Biden announced his support for gay marriage in 2012, he cited the TV show Will & Grace: “Things begin to change when social culture changes,” Biden explained. Indeed, the cultural revolution was responsible for groundbreaking films such as Midnight Cowboy (1969) and Brokeback Mountain (2005), Broadway shows such as A Chorus Line (1975) and Rent (1996), network television such as Modern Family (2009–present), as well as Andy Warhol, disco music, and countless fashion trends that both shaped and dovetailed with political initiatives. This new public openness about sexuality was as much a part of the homosexualization of America—and loosening of heterosexual ideals and norms—as any legal success. Indeed, Faderman argues it made legal success all but inevitable.

• • •

My roots in the Gay Liberation Front sharpened my anticipation of Jim Downs’s Stand by Me, with its focus on gay male culture in the 1970s.

Downs began his project in response to the 2005 documentary Gay Sex in the 70s, which chronicles a mostly urban and male gay social scene from Stonewall to 1981, when AIDS first became known in New York City. Downs takes exception to the film for two reasons. First he argues that it panders to popular misconceptions about LGBT history, which take a teleological—one might say mythic—view of the 1970s as a debauched period that had to conclude with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This narrative sidelines other political and social activities of the era. Downs’s second complaint is that the film focuses on the 1970s as an era of sexual promiscuity, which distracts from the fact that “sex was only part of what had mattered to gay men as they began to make gay liberation meaningful in their lives.” This strikes me as a curious statement, since no one familiar with the era would ever dispute this, nor claim, as the book’s subtitle does, that this history has been “forgotten.” Even a quick reading of Faderman, for example, would quickly put the lie to this. Downs’s stated thesis may speak truth to a certain amnesia in popular culture, but the significance of his book lies elsewhere. For Downs artfully draws on an array of primary sources to scrutinize how social movements themselves imagine, enlarge, and distort our understanding of them.

Undoubtedly, the cataclysmic advent of HIV/AIDS did recast the ’70s in a way that partially obscured reality. The disease stoked fantasies in which sexual freedom leads inexorably to death. This narrative was, unsurprisingly, popular among conservative Americans. But the LGBT community, too, embraced it—although for different, if equally mythopoetic, reasons. For the emerging New Right and its Christian fundamentalist supporters, HIV/AIDS was a moral bookend to what they saw as the immoral promiscuity and cultural degeneration of the 1970s. For many in the gay community—especially men who lived through the decade, and perhaps younger men who view it nostalgically—the sex-filled ’70s was a time of unparalleled sexual freedom. It represented a perfect, lost moment in time, populated by angels who burned too bright to last. These understandings of the 1970s seem to cut in opposite directions, but the decade is poorly served by both.

Gay life and politicking in the 1970s constituted a breathless and confusing rush to empowerment. It was defined, as much as anything, by the feeling of everything happening all at once.

Although Downs values the role of sexuality in LGBT culture, it is no surprise that some critics read Stand by Me as diminishing the place of sex in the decade and the movement. Downs himself seems conflicted on this issue. “The stories in this book reveal that many gay people sought community and their own culture over legal rights and political recognition,” he writes. But at times he also seems to be arguing that many gay folks sought community, culture, and religion over sex. The more accurate description—that many sought these things alongside sex—emerges clearly from Downs’s sources. For example, a gay man from Boston who states that in the 1970s “there [was] no conflict for me in worshiping Jesus at service and then running out and sucking cock in the shrubs at the Fenway.” Part of what was revolutionary about queer identity in the decade was the sense that such things need not be mutually exclusive—that, quite the contrary, they could be mutually reinforcing.

For the most part, that is the story that Downs’s research tells. He has combed through a wealth of archival materials, including gay community publications, the holdings of LGBT religious groups such as the Metropolitan Community Church (a Protestant denomination founded in the late ’60s as a safe worship space for homosexuals), the personal collections of men doing prison work on gay issues, archives of LGBT community centers, and reporting on LGBT life in mainstream publications. These resources have been underutilized by scholars, and Downs’s work is a service both to the historical record and to the gay community.

Downs has an instinct for historically relevant stories, and he tells them well. This is tragically evident in his first chapter, “The Largest Massacre of Gay People in American History”—or what was the largest, until the Orlando shooting. On June 24, 1973, in New Orleans’s French Quarter, the UpStairs Lounge was set on fire. It was the last evening of New Orleans Gay Pride, and the city’s Metropolitan Community Church was hosting a service in one of the function rooms of the second-floor gay bar, which also hosted theater, worship, and other events. Someone—no one was ever convicted—set fire to the carpet and drapery on the stairs. Within twenty minutes, thirty-two women and men were dead. Fifteen more were seriously injured. The city and mainstream media were indifferent; some New Orleans churches refused to host funerals for the victims. By contrast, the burgeoning gay press across the country covered the arson avidly, providing a rich archive on which Downs draws. As horrific as the UpStairs Lounge fire was, Downs notes that it was only one in a long string of attacks, mostly arson, against gay houses of worship throughout the 1970s. Downs’s reporting on the UpStairs Lounge fire is moving and, more important, illustrates the adversity gays and lesbian faced in their efforts to create community and culture that reflected and sustained their lives.

In the chapter “‘Prison Sounds,’” Downs offers similarly invigorating detective work, digging up aspects of LGBT activism that have eluded most historians. Publications such as Boston’s Fag Rag (1971–early ’80s), San Francisco’s Gay Sunshine Journal (c. 1970–82), and Toronto’s The Body Politic (1971–87)—all publications with roots in gay liberation—reached out to gay and lesbian prisoners, published their writing, and built a support network for them. In today’s world of LGBT respectability politics, the concern for gay and lesbian prisoners is negligible to nonexistent. There is a key irony here: as Faderman demonstrates in The Gay Revolution, the mainstream LGBT movement has often been concerned with eliminating laws that criminalize homosexual acts and affect, but has rarely extended such concern to queer prisoners themselves, especially if their sexuality was not the direct cause of their imprisonment. Efforts toward prison reform, and gay liberation’s commitment to prison abolition, have never been part of the mainstream LGBT political agenda.

LGBT-centered churches also played a part in prison outreach. The Metropolitan Community Church created the publication Cellmate to help prisoners find pen pals and lobby for changes to the criminal justice system. These programs gave voice particularly to queer African Americans and Latinos, an especially remarkable achievement in the context of an LGBT movement that has long been criticized, and rightly so, for its overwhelming whiteness. In retrospect, these efforts were decades ahead of their time, anticipating key concerns of Black Lives Matter and others committed to ending the hyperincarceration of people of color and the social death of inmates.

In the course of my long involvement with Fag Rag and Gay Community News (1973–92), I witnessed considerable pushback against these projects. Some resistance came from queers who believed deeply in the judicial/carceral system and felt that prison reform had nothing to do with the struggle for gay rights. Some came from men who had been scammed by prisoners. But while this did happen occasionally, anxiety about it far exceeded its actual risk. Alongside personal ads from prisoners, the national, mainstream Advocate frequently ran warnings about possible extortion scams, further stigmatizing incarcerated people.

It is easy to claim, as many at the time did, that Christians and prisoners don’t have much to do with queer activism. Downs helps us understand the narrowness of this view. Gay liberation was an impulse to personal freedom. Sometimes that meant re-envisioning Christianity as LGBT-friendly, sometimes it took the form of fighting the carceral system, and sometimes it meant engaging in and building a community around sexual contacts. None of these impulses was entirely separate, and they cannot be made so. Often the same people were doing all of these things—and more—at the same time. If this is hard to grasp, it is a function of how we conceptualize history as discrete elements competing for prominence in a larger narrative. Gay life and politicking in the 1970s constituted, for me and many others, a breathless and confusing rush to empowerment. It was defined, as much as anything, by the feeling of everything happening all at once. Capturing this sense of profound entanglement is a tremendous challenge for any historian of the period.

• • •

Despite their differences, The Gay Revolution and Stand by Me articulate an underlying sensibility of comradeship and struggle. This is arguably the soul of the LGBT movement and most other progressive movements for social change. These personal interactions within social movements are the subject of Benjamin Shepard’s Rebel Friendships.

Shepard, whose dazzling Queer Political Performance and Protest (2009) offered an analysis of the role of play in political protest and resistance, has written a common-sense challenge to existing theory on the nature and organization of social movements. He argues that “rebel friendships,” bonds forged contrary to existing social norms, are the glue that holds progressive social movements together.

Wildly expansive in his discussions of friendships, Shepard begins by evoking Huckleberry Finn and Jim, Rick and Captain Renault from the 1942 film Casablanca (“This is the beginning of a beautiful friendship”), and even J.R.R. Tolkien’s wizard, Gandalf (“In this matter, it would be well to trust rather to their friendship, than to great wisdom”). The German anti-Nazi group White Rose—a band of rebel friendships if ever there was one—was characterized by member Franz Muller in these terms: “Friendship and freedom were the values most important to us.” Shepard argues that ties of friendship, perhaps even more than biological ones, are what cement human relationships and keep our social systems intact.

Shepard is not a sentimentalist about friendship, and he is not concerned with people getting along nicely. Rather, his vigorous analysis of theories of friendship—from Aristotle to Foucault—is predicated on the idea that friendships often grow out of tension. Shepard argues that “every relationship takes a dialectical shape, from formation to conflict to either a resolution and some sort of new awareness or a rupture.”

Shepard draws upon the idea—embedded in the radicalism of the late 1960s and ’70s—that the personal is the political. Rebel Friendships enlarges on this truism by nodding to anarchist theory. Quoting Emma Goldman, Shepard notes, “Anarchism stands for a social order based on the free groupings of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth.” By “social wealth,” Shepard means the elaborate infrastructures we create to nourish the things and ways we love.

Viewed through Shepard’s lens of friendship, Downs’s Stand by Me makes more emotional sense. Rebel Friendships highlights the fallacy whereby sex in the 1970s obscures the essence of gay liberation. Rather, Shepard insists on the profound interconnections between sexuality and political engagement. Citing CrimethInc.’s pamphlet “Fighting for Our Lives: An Anarchist Primer” (2010), Shepard takes Goldman’s ideas a step further: “In the egalitarian beds of true lovers, in the democracy of true friendships, in the topless federations of playmates enjoying good parties and neighbors enjoying sewing circles, we are all queens and kings.” The sweep of Faderman’s narrative and the closer readings of Downs’s stories are refigured here in CrimethInc.’s lovely conflation—and transfiguration—of beds and friends and lovers and sewing circles producing real social change. Shepard writes:

We have considered a few of the ways in which friendship helps regular people challenge social controls and what happens when activists, or anyone for that matter, lose connection to community. The point . . . is that social movements are far better positioned when motivations include love, care, and connection with others, as opposed to guilt or anger. When affection and friendship are involved, we find new vocabularies of care and connection outside institutional channels.

Reading The Gay Revolution reminded me of the sheer energy and grandeur of the LGBT struggle for freedom. Stand by Me conjured up the intricate, often forgotten details of the heady years just after Stonewall. Rebel Friendships, however, came closest to conveying the sheer emotional and intellectual exaltation of the early movement: complicated, confusing, messy, overwhelming, and foremost mentally and physically provocative. Rebel Friendships destabilizes the political narrative rather then attempting to find a cohesive presentation of it.

By focusing on the importance of affinity and chosen family—the rejection in queer life of the biological family in favor of the open, polymorphous plurality of community—Shepard explicates the inner workings of the history Faderman and Downs narrativize. In doing so he captures the best impulses of those who have fought for queer freedom.