“Woman loves sex and loves children.” These six words, written in 1927 in The Right to Be Happy, sum up the passions that drove the life and politics of Dora Russell (1894–1986), British feminist, sex radical, progressive educator, peace activist, and second wife of the philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell.

The desire for sex unfettered by gods or masters marked Dora as a woman of her time—or rather, a New Woman of her time. The zealous love of children—she had four and ran a school for fifteen years—made her a little old-fashioned. Her insight that the body is political, in sex and motherhood, put her ahead of her time. “What has feminism to do with mothers?” wrote a female reviewer in 1925 of Russell’s first book, Hypatia, or Women and Knowledge, a feminist brief for women’s sexual freedom and against marriage.

But Dora’s times also rendered her twin desires for freedom and family nearly incompatible. Ditto her hungers for heterosexual romance and sexual equality. Bertie Russell married her as a comrade and co-parent. But he expected “bottle-washing,” as she put it, and, when they divorced, deployed every jot of his patriarchal privilege to crush her. Her lover Griffin Barry, the American journalist who fathered two of her children, dipped timidly into Hypatia, then penned a letter “to the woman behind the gun, whom I prize so much when she’s doing her hair and talking nonsense.”

Public male allies of women’s cause were patronizing or downright sexist in private. Her friend H. G. Wells—who renamed his wife “Jane” because her given name didn’t sound wifely enough—declined to endorse Dora’s 1924 run for Parliament. Instead, he sent this encouragement: “I cannot imagine any woman in Chelsea can vote against you.” And any man in Chelsea?

Like Emma Goldman, Dora could abide no political system that would alleviate economic misery while ignoring ordinary unhappiness, especially women’s. But she believed in the power of institutions to advance women’s emancipation. What heartened her most about Revolutionary Russia, for instance, was its swift reform of divorce laws and decriminalization of abortion.

Yet the institutions into which Dora poured her hopes insulted and sidelined women. In 1924 she trekked Britain persuading rank-and-file Labour Party supporters to back legalized dissemination of birth control information. Then at the 1925 convention, the leadership overruled the majority. “I hate the Labour Party,” she wrote Bertie, “and men are quite disgusting.”

That year the Times Literary Supplement dismissed Hypatia as written “in a temper.” You bet it was.

Dora’s vision of the good society began in the embrace of heterosexual lovers and the “instinctive” altruism of parents. “Everything that is lovely, intelligent, vital in communal life comes to it through the intensity of life in individuals,” she wrote in The Right to Be Happy. “The function of the state is merely to set men free and settle the background against which singly and in free co-operation men and women will continue consciously and unconsciously the evolutionary process.”

But besides love, another flame—rage at men, both legitimate and neurotic—ignited Russell’s activism, while scorching her intimate life. Like feminists from Mary Wollstonecraft to Tina Fey, Dora understood her personal troubles to be political. So when sex-love let her down and she turned her whole heart toward children, it is no surprise that her politics took that turn too.

Russell could abide no political system that would alleviate economic misery while ignoring ordinary unhappiness, especially women’s.

She became a “maternalist.” To her—as to a long line of feminists (and conservatives) before and after her—motherhood, or even its potential, made women not only different from but better than men, more nurturant, peaceful, and trustworthy to safeguard the earth. At barely forty, she pretty much wrote off men as politically and personally hopeless.

The conflicts between family and freedom, sexual love and gendered anger afflict women to this day. Dora Russell’s failed attempts to reconcile them—and the unhappy solutions this crusader for happiness ultimately grasped—make her life a poignant parable for contemporary feminists.

According to her autobiography’s first, charming volume, The Tamarisk Tree: My Quest for Liberty and Love (1975), Dora Black was destined to be a feminist and social reformer. The little girl was stirred by indignation watching her mother justify each household expenditure to her father. The grammar school pupil joined the Children’s League for Pity, which brought flowers and old toys to hospitals. At high school Dora and her pals tore around suburban London behaving precisely as the students across the street at the School for the Daughters of Gentlemen would not. Although marriage would make her Lady Russell, she vowed never to be ladylike, and she kept the promise.

But she also liked men and men liked her. It was her father, a senior civil servant, who sent her to the best schools, who coached her for college entrance exams. With him, at twelve, standing in the cheering, booing crowd in Trafalgar Square watching the 1906 general election results, she first felt the thrill of politics. “I was carried away by mass emotion,” she wrote, “utterly intoxicated with it all.”

In 1912 Russell won a scholarship in languages at Girton, the women’s school at Cambridge. There the polymath editor C. K. Ogden took her under his wing. She was reading the early eighteenth-century French hedonists and linking their ideas of the right to happiness with the Enlightenment’s democratic revolutions. At Ogden’s Heretics Society, she absorbed the successors of that politically enlightened pleasure-seeking—anti-authoritarian socialism and sexual libertarianism—from the cream of Britain’s left-wing modernist intelligentsia. “I used to bicycle off [to Ogden’s] of a Sunday evening,” she recalled, “with the most agreeable feeling of defiance and liberation.”

She met Bertrand Russell, arguably her greatest mentor, on a walking tour of the moors in 1916. By candlelight at a little inn, he asked his three young companions what each wanted in life. Compelling work, a world-changing cause, the others answered. And Dora? She didn’t hesitate: marriage and children. Dora was forthrightly sexual, her wide-set eyes vividly intelligent. Russell—forty-five, in a childless, moribund marriage and partial to women half his age—was intrigued.

Some time later at tea in London, Dora clarified: not a conventional monogamous marriage, of course. Of course, he agreed. But if children resulted? They should belong to the mother, she asserted. “Well, whoever I have children with, it won’t be you,” he sniffed. He was wrong, she wishful.

She went to America with her father, sent to persuade the United States, by then engaged in World War I, to share oil supplies with the British Navy. Sailing west, she lost her virginity with a dashing Navy captain. Dining with tycoons tallying their war profits confirmed her pacifism—another thing that drew her to Bertie, who lost jobs and went to prison for supporting conscientious objectors.

On her return they became lovers. Bertie’s love life was already complicated. He was seeing both Ottoline Morrell and the actress and pacifist Constance “Colette” Malleson. “Dora loves me, I love you, you love Casson, he loves his wife,” he wrote Malleson in 1920, when he had probably told Dora the affair was over. “Where is happiness to be found in all this chain?”

But Bertie did find happiness with Dora. He badgered her to marry him. Lord Russell wanted a legitimate heir; he could not respectably divorce with no new wife on tap. Dora was just twenty-five, footloose in Paris, reading at the Bibliothèque Nationale and “sketch[ing] notes for a satirical musical about concepts of God.”

She wrote Ogden, “The kind of slavery he wants me to accept is what he, at my age, would have emphatically denounced . . . . But he hates an irregular relation and wants absolute surrender or a complete break.” She dreaded either, but this New Woman was ready to sacrifice for love. “I do want to try and do what is best for his work and him without destroying myself.”

She solved the dilemma unconsciously, you could say, by not using contraception. Within months she was pregnant. They married—without vows of monogamy—in 1921, two months after their son John was born.

The dozen years with Bertie were mind-reelingly fruitful. Dora had four children, published four books, founded a school, ran for Parliament. Losing the election did not slow her down. After one political victory a postcard arrived from Wells: “Hooray! You DO things! I just write about them.” He called her his “man of action.”

In writing, speaking, and organizing, Dora always linked sex and socialism—pay for housework with fair industrial wages, the intimate labors of women with the sweated labor of men. Pregnancy was four times more fatal than mining, the most dangerous of occupations, she told Parliament and the minister of health. Her Workers’ Birth Control Group of activists and progressive members of Parliament explicitly allied with Labour to distance itself from the eugenic ideologies of birth control advocates such as Marie Stopes, who would limit the propagation of the genetically inferior working classes. A “trade union of lovers,” Dora proclaimed, will “conquer the world.”

Countess Russell’s sympathy for the working classes was not immaculate of class bias, of course. As the historian Stephen Brooke points out, she saw sex and motherhood as elating and elevating for middle- and upper-class women. But the bodies of poorer women were only broken by sex and pregnancy—venereal disease, prolapsed wombs, botched abortions. D. H. Lawrence contrived a gardener awakening his aristocratic mistress to sexual rapture. But Dora could not imagine such a man doing the same for his own wife.

The Russells’ joint commitment to freedom, pleasure, and happiness—especially children, including their own—drove their decision in 1927 to found the alternative grammar school Beacon Hill. Like A. S. Neill’s Summerhill, Beacon Hill School imposed as few rules as possible: tooth-brushing was compulsory; clothes were not. Unlike Neill, though, the Russells wanted rigorous academics, without crushing the exhilaration of learning. So science involved forays to the woods. The kids chatted in German and French, mounted original plays—The League of Notions, Cats Have No Fun. Minutes of the Everything Society—presentations covered witchcraft, woodpeckers, Hitler, the human skeleton—show the breadth of inquiry and interleaving of social and intellectual life at the school: “Jeremy made a nuisance of himself. The sting-winkle has a very pretty shell.” Numerous pupils, according to Dora, went on to prestigious secondary schools.

In 1929, with the Australian gynecologist Norman Haire, Dora did the mule’s work of pulling together the London Congress of the World League for Sexual Reform, a five-day confab where medicine met sex radicalism. Topics from psychoanalysis to prostitution, contraception, and censorship were debated. Haire was widely mistrusted as an arriviste, but the Russells’ good names attracted the attendance or endorsement of dozens of celebrities—George Bernard Shaw, Havelock Ellis, Radcliffe Hall, Margaret Sanger, even Sigmund Freud. The eminent sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, the first champion of homosexual rights, spoke. In Berlin, to Dora’s astonishment, he introduced her to two transsexuals.

As for Dora, she discoursed on marriage and freedom, arguing that laws should be based on reason and personal integrity, not religious piety or social propriety. The physical rapture and emotional harmony of lovers, she declared, modeled a “morality directed to human happiness.”

While agitating for their principles in public, Dora and Bertie were testing them at home. Both had other lovers; the lovers were sometimes dealt with jointly. “For some weeks I have wished to express my gratitude for your generous conduct since you have known that Dora and I love each other,” Bertie wrote to an erstwhile paramour of Dora’s. When she got pregnant with Griffin Barry, Bertie welcomed the child, who was registered as Harriet Ruth Barry Russell.

Beneath the genteel surface, however, Bertie was chafing. He became impotent with Dora after their second child, Kate. His diaries reveal a man in philosophical and personal despair—disillusioned with socialism by the dogmatism and repression he’d seen in Russia, doubting his pacifism as fascism rose in Europe. At the school, conceived as a sweet democratic republic of children, he found himself forever defending the weak and small from the bullies. In a 1931 entry he admitted that even the vast universe, which had always elated and consoled him, now offered only “darkness without, and when I die . . . darkness within.”

Pregnancy was four times more fatal than mining, Russell told Parliament.

He told Dora he was in love with Patricia “Peter” Spence, the children’s twenty-one-year-old governess. To save the marriage, or maybe kill it, he proposed a vacation à quâtre near Biarritz—Bertie and Peter and Dora and Griffin, with the three kids in tow. Blissful it was not.

Dora, too, was pressing her luck. The next year she got pregnant again with Barry and swept off to Majorca with him. Bertie initiated divorce.

With the deterioration of her marriage, Dora’s rhetoric toward men turned snide, her maternalism more marked. “It is curious how tenaciously men cling to the theory that women are neither realistic nor rational,” she wrote in Spain’s El Sol, where she contributed a column from 1926 to 1930. “Like men we have a romantic period in adolescence, but then we grow up, and they so often don’t.”

Maternity—[the] essential fact which divides women from man—makes us executive and practical. . . . It is easy [for men] to embark on fantastic national adventures to distract people; it is hard to do all the dull detailed work necessary to organize for individual and social happiness.

Once she had held that men could nurture as well as women. Now the “essential fact” of motherhood, coupled with men’s immaturity, made women the only rightful guardians of happiness.

The divorce was as vicious as they come. “My view is that she intends to get custody of the children through the divorce in which she will blacken me and whiten herself,” Bertie wrote his solicitor. “Dora is slippery, and very wicked; we must be careful.” In letters to Barry, she was equally paranoid and self-justifying. Where Bertie was cold, she was hysterical.

After three years he outgunned her with his money, his prestige, and the law he had long decried, which gave him every right and her none. He didn’t leave her with nothing, as she later claimed. She had Carn Voel, their big white house overlooking the cliffs and the crashing Cornish sea, where they’d spent blissful summers with the children. She had child support and alimony. She had the school, though he publicly denounced it and withdrew his funds and his children, and she spent the decade until its closure in 1943 dunning her friends for money. And anti-aristocratic sentiments notwithstanding, she kept the Russell name and her title.

It is hard to figure out how much money she ended up with. She worked steadily and lived simply but also traveled widely and kept two households. Her alimony ended when Bertie died, and she suffered some thin times. But by the 1980s, when visitors arrived at Cornwall, she would send a chauffeur to the station and introduce them to the gardener at the house.

The school and her books made Dora something of a progressive child-rearing pundit. She toured America “and enjoyed odd pockets of transatlantic influence,” Brooke writes, noting, “The Right to Be Happy became a bible for free-thinking bohemians” in Montreal. Her advice column in the Manchester Sunday Chronicle evinced contempt for harsh parenting practices and respect for children’s feelings, intelligence, and individuality.

But the clashes with Bertie and Barry took their toll on her own offspring and frayed her relations with them. “Children, like women and the proletariat, are an oppressed class,” Dora wrote in In Defence of Children (1932), published just as Bertie was walking out. With desperate, often petty salvos at her ex-husband, she was fighting to hold her family together—defending her own right to happiness. That abstract political connection among her children, herself, and the working class must have offered Dora shallow consolation.

Unlike Bertie, who left three wives, each for a new and younger love, Dora loved loyally and consorted with ciphers on the side. Barry was constantly mooching subsidies to tide him over until the next big assignment, which rarely materialized. Rather than solidifying their bond, shared parenthood only nettled. “You cannot claim rights without accepting some responsibility,” she wrote in one exasperated missive. Indeed, such a luftmensch was Barry that his daughter, Harriet Ward, entitled her biography of him A Man of Small Importance.

While still with Barry, Dora fell for Paul Gillard, a handsome rapscallion, sometime novelist, and Communist organizer. Bertie called him a “drunken homosexual spy”; he was probably the first, definitely the second, and maybe the last. When he was found dead under a bridge, Dora devoted herself to proving he had been murdered by fascists. She declared him her life’s great love—greater even than Bertie. But biographers conclude the feeling was not mutual, or even, possibly, consummated. It also seems that Barry, a bisexual, propositioned Gillard while they were both visiting Dora.

Her last involvement was with Pat Grace, a friend of Gillard’s who showed up skinny and ragged as a hobo at one of Dora’s lectures. She took him in as a secretary at Beacon Hill, though no one else quite knew what to make of him. Her daughter Kate called him “Dora’s faithful hound”; another pupil recalled his “somber, mute presence.” Dora married him during World War II, for the soldier’s benefits and his help running the school. But, as she wrote in her autobiography, “The quest for love had ended in the shattering tragedy of [Gillard’s] sudden and mysterious death.”

The woman who loved sex and loved children seems to have regarded her lovers as children—or chosen grown babies as lovers. It was never the great public intellectual she loved, but the impish, and vulnerable, Bertie Russell. A telling episode: swimming during their first sojourn as lovers, he collapsed on the shore. Dora revived him, writing later that at that moment she felt “more sure than ever that he needed someone with sense to take care of him.” Barry patently needed a mommy as much as a partner. Gillard was as impetuous as a teenager and almost as young. And Grace? At Beacon Hill, Dora’s son Roderick noted, “Mummy, you have five children now, because [of] Pat.”

Motherhood was Dora’s first ambition. Now, finished with men, it became her political identity and raison d’être. A pacifist since World War I, in the 1950s she again took up the work for peace and nuclear disarmament, as well as environmental conservation, that would consume her for the next three decades.

Her memoir and papers from this time are a parade of mothers. For the 1955 Women’s International Democratic Federation’s World Conference of Mothers in Lausanne, she sent out hundreds of invitations, translated into thirty-two languages, to professionals, workers, peasants, students, journalists, and diplomats on every continent. The Federation urged them to speak up as mothers “for the defense of their children against war, for disarmament and friendship between the peoples.” The conference, which, she said, steered clear of political movements including feminism, established the Permanent International Committee of Mothers and named her secretary. She and an Italian committee member authored the “Mother’s Declaration to the U.N.,” arguing that the Cold War climate harmed children’s moral development.

From her dining room table, Dora created the Women’s Caravan of Peace of 1957–8—a dozen women in a claptrap coach traveling from Edinburgh through Europe and the Soviet Union to Moscow and back. Unfurling their multilingual banners declaring “Women of All Lands Want Peace,” they stopped along the way to join women’s conventions and demonstrations, improvise border-crossing ceremonies, accept cakes and flowers—activities, as one observer put it, such as “dancing with a dragon in Red Square.”

Dora went numerous times to the Soviet Union, usually to attend this or that peace or women’s congress. But she was not a card-carrying communist—“she lacked the fanaticism of the revolution and she wasn’t sectarian,” said Cathy Porter, the biographer of the Russian feminist and revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai, whom Dora met briefly and idolized. Dora “worried, correctly, about the ‘religion’—the dogmatism” of Marxism. Still, the naïve eyes that surveyed “a vision of a future civilization” in Russia in 1920 were blind to the violence and repression already underway.

Throughout her life Dora rejected both right- and left-wing anticommunism (including Bertie’s and Doris Lessing’s). She called her stance a challenge to the Cold War, which it was; but it also bordered on apologia. In her memoir’s close account of 1956, for instance, there is a curious gap where Khrushchev’s revelations of Stalin’s murderous purges and gulags should be. And two years later, the Women’s Caravan accepted the Kremlin’s hospitality, no doubt acting the gracious guests.

In the arms race, however, Dora rooted for neither side—or rather, she drew up different teams. The detonation of the atom bomb, she later wrote, jolted women awake. If men had perverted physics to produce this abomination, what else might their “multifarious” scientific escapades yield? “Women had, with misgivings, been obliged to trust men as husbands and fathers. But now suddenly came enlightenment: Why have we let them go on disposing at will of the children that we bear?” Capitalist or communist, she wrote in 1965, “fundamentally, men have always loved themselves and their purposes better than they have loved women.” It was past time for women to “go it alone.”

Russell was fed up with men, but not about to take off for a ‘wimmin’s’ festival.

In fact women all over the world were making separate claims as women for peace. Groups such as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and, in the United States, Women Strike for Peace, also deployed the metaphors and moral authority of motherhood to press their case. When Strontium-90—a radioactive isotope resulting from atom bomb tests—was discovered in the U.S. milk supply, they protested on behalf of children’s health, pushing forward the 1963 Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed by the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union. Of course, male protesters, including those in War Resisters International and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, contributed equally.

Even after old age grounded her, Dora cheered on the women peace activists going it alone. Among these were the protestors of Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, a tarp-and-tent bivouac set up in 1981 outside a U.S. Air Force base in rural England, where NATO had installed ninety-six cruise missiles. Resolving to stay until the missiles were gone, the women sang, cooked, tended children, and inventively and nonviolently disrupted the war machine. The campers survived the cold, outwitted evictions, and changed personnel, but the group never left. And, partly thanks to the global attention it drew, in 1991 the missiles were removed.

Greenham brought together women of every activist stripe. There were confirmed separatists, whose lives were severed from men in virtually every aspect, from music to religion to sex. And there were those who put up with the camp’s separatism because they refused to leave to men the life-and-death decisions that imperil everyone. Dora fell somewhere in between: fed up with men, speaking as a mother for children and humanity, but not about to pack a knapsack and take off for a “wimmin’s” festival.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Dora was one of the few women in her upper-class bohemian and radical circles who actively parented. She always had household help, mind you—husbands came and went, but nannies were forever, one journalist quipped—but four kids are a lot. That lot deepened her sympathy with the working-class women on whose behalf she organized.

But motherhood also isolated her, even from the politics of motherhood. She missed the 1955 Lausanne conference, and many other events, in order to care for her son John, who succumbed to disabling mental illness in 1954.

Another grievous twist: pacifism rooted in parental love, which she passed on to some of her children, hung in the background of two losses unbearable for any parent. Her youngest child, Roderick, a Korean War resister, was assigned to service in a coal mine where he was accidentally paralyzed from the waist down when he was twenty-four; he died at fifty, before she did. And her darling granddaughter Lucy, daughter of John and probably severely depressed, immolated herself in protest of the Vietnam War.

By the time of Lucy’s death, Dora had sold her London flat and decamped with John to Carn Voel. With papers stacked to the ceilings and rats in the back rooms, she kept working—writing articles and letters, engaging in local civic activities, traveling to speak when she could. “I never stopped writing. I just got ignored,” she told the Australian feminist Dale Spender, who interviewed her in the 1970s. “The men controlled the publishing industry.”

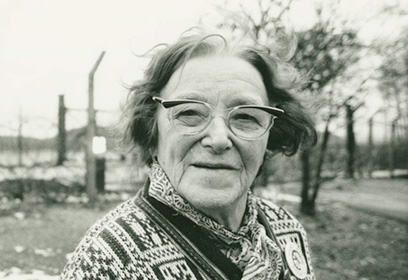

In Dora’s final decade, feminists found, feted, and published her—the autobiography, an anthology, and a tract against the “religion” of industrialism. She appeared on the cover of Time Out. The BBC led its 1984 series Women of Our Century with her profile. Warren Beatty paired her with Rebecca West among the two-dozen desiccated, and anonymous, “witnesses” in his film Reds (1981). Journalists schlepped to Cornwall and reported back about this “sharp and lovely,” “intrepid,” and “vigorous” old lady who was having liberated sex before their readers were born.

The media also trivialized her. “Cleaning Up After Bertie,” the Sunday Times headlined its notice of the BBC program. The Daily Mirror compounded its usual sexism with ageist ridicule: “Dora and the Sexy Shocker!” And Beatty edited West’s and her testimony down to gossipy snippets. History, with a capital “H,” was left to the men.

Dora remained smart, hardy, and admirably cranky. “Effortlessly brilliant,” Porter says. “Grand, outspoken, and courageous,” recalls Lennie Goodings, editor-in-chief of the British publisher Virago. The novelist Drusilla Modjeska made a pilgrimage to Carn Voel when Dora was eighty. “She took me down the steep path to the beach,” Modjeska told me. “What I remember is the lick at which she went back up the track, and how pleased she looked when I puffed up minutes later!”

But Dora’s politics were not as agile as she was. What she seemed unaware of—or uninterested in—were the debates going on not just at Greenham but throughout the women’s peace movement.

Most everyone agreed that women have a critical perspective on war, which afflicts them and their children through hunger, displacement, rape, and widowhood as catastrophically as it does male combatants. Women, meanwhile, are rarely in the rooms where those wars are declared or the truces negotiated. They must be heard.

But do women have a special sex-selected duty to stop people from killing each other? Or, as the feminist scholar Ann Snitow put it, does assuming the part of the nurturant mother defending her cubs against the deadly dad only exaggerate the divisions that make war men’s work while women stay home with the babies?

Critical to these questions is another: whether women are the essential solution because men are the essential problem. In the fifty years since Dora joined the peace movement, many feminists have drawn a distinction between men and masculinity, one of whose spawns is militarism, the ideology that might makes right and rationality should triumph over emotion. But masculinity is neither all bad nor reserved for men. Indeed, some women adopt what the queer theorist J. Jack Halberstam calls “female masculinity.” And there had to be a reason beyond masochism that Dora’s lovers were all, each in his own way, exceedingly masculine.

Dora was not advocating that women take over the world, put men in cages, and treat them the way men have treated women for millennia. But she was not waiting for men to clean up their mess, either. Asked near the end of her life if there was any hope for the human race, she replied, “Women are the one chance.”

Sadly, this woman who longed both for men and for peace finally felt she had to choose one or the other. At Land’s End geographically, she had backed herself into a political fastness, far from the feminist conversations that were yielding both a more nuanced understanding of gender and an increased tolerance for ambiguity—and with these, for men. Even among the separatists, man-hating was mellowing. When Porter visited Greenham in the early 1980s, the campers barred all males from entrance, including her baby son “in nappies.” Some years later, Snitow spent time at the site and wrote down this self-mocking ditty: “We’re mostly vegetarian / except when we’re devouring men.”

At Carn Voel Porter found Dora “humbled by life” but “without bitterness,” buoyed by “a rough humor.” One hopes she would have gotten the joke.