On paper, Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude has one of the strangest, most unworkable premises of any commercial American movie: it’s a comedy about suicide, in which much of the action takes place at funerals; a romance in which a gaunt teenage boy and an eighty-year-old woman wake up in bed, hazy with soft-focus sunshine. In 1971 it was a box-office flop, not surprisingly, and the subject of critical derision—“Harold doesn’t even make pallbearer,” Roger Ebert quipped. When I saw it for the first time, in 1988, Harold and Maude had—with The Smiths, Joy Division, and Violent Femmes, with Catcher in the Rye and The Bell Jar—become a rite of passage, almost a sacrament, for teenagers like me. That is, smart, awkward, self-conscious, unathletic, artistic—probably, though not inevitably, white. The film worked. It showed me, I think, that I didn’t have to waste my time hating my parents, that I could turn my morbid anger into bemused subversion (a lesson I took years to appreciate) and channel my loathing for the given world, the adult world, into art.

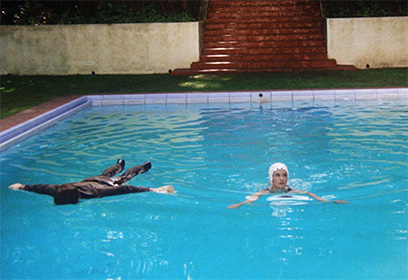

Harold and Maude begins as a movie about adolescence at its most acute: Harold, a morbid, petulant, fixated comic genius and prep-school dropout, the only child of a wealthy widow and socialite, stages theatrical mock-suicides on the grounds of their California mansion—dangling from a fake noose next to the piano, floating facedown in the pool, burning alive in a Buddhist monk’s robes on the patio. In his spare time, he visits strangers’ funerals. At one of these he meets Maude, a well-preserved bohemian who claims to be descended from central European royalty. She bears a tattoo from a German concentration camp, has dabbled in various art forms—Harold gets his head stuck inside a large wooden vulvar sculpture in her living room—and steals cars as a kind of spiritual vocation, reminding people, “Here today, gone tomorrow.” Maude appears to be the first person—would that every sensitive, bored, artistic teenager had such a first person—to take him seriously on his own terms. He becomes her partner in crime: their theft of a dying tree from a street-side planter results in one of the funniest chase scenes in film history.

What makes Harold and Maude so jarring is that it oscillates between two moods we have been trained to think of as mutually exclusive. On one hand, the film takes the kind of reflexive cynicism about American life that we associate with its era—think of the oily executive in The Graduate (1967) whispering “plastics” in Dustin Hoffman’s ear—to a comic-grotesque extreme. On the other hand, Harold and Maude is also, in a resolutely unironic way, a movie about refusing death—about growth, self-transformation, and resistance to authority. For Harold, Maude is a lover, confessor, and therapist, as well as the mother he never had; in her presence, he breaks down and weeps for the first time, describing his ruinous, isolated childhood. For Maude, Harold is the last best chance to leave an imprint on the world: she has always vowed to end her life before she turns eighty, and true to her word, and Harold’s horror, she takes an overdose of pills on her birthday. Harold drives his Jaguar off a cliff at Big Sur but tumbles out at the last minute, and takes off over the hills, plucking the banjo Maude taught him to play.

What I didn’t grasp when I first saw it—could not have grasped, as a privileged child myself—was the degree to which Harold and Maude, even at its most iconoclastic moments, is conditioned by, almost suffocated by, impunity. The vast, echoing rooms of Harold’s mansion—the free space created by his wealth—allow us to suspend our disbelief and permit the movie to work its particular sleight of hand: to take the most radical cynicism and turn it into a feeling of liberation and joy. This particular caricature of privilege, in other words, is what makes Harold and Maude so easy to dismiss—what makes it feel not only “unrealistic” (whatever that means) but precious and naïve. But it is also the key to the movie’s subversiveness. Harold and Maude becomes so much more valuable, and interesting, if we stop thinking about it as therapy for wounded, cynical adolescents and view it instead as a therapeutic, and largely forgotten, critique of wounded, cynical, privileged artists—trapped in their own mansions, setting fire to their own robes, and willing to risk anything, even liberation and joy, to get out.

I Bite People To Save Them

Diogenes of Sinope, the first cynic (or, properly transliterated from Greek, “kynic”) had no fixed address. He lived in a dry cistern near the marketplace in Athens and identified himself with dogs; “kynic” is derived from kynikos, “dog-like.” “Other dogs,” he reportedly said, “bite their enemies. I bite my friends to save them.” Scorning the artificiality and hypocrisy of Athenian society, he also called himself—and invented the term—cosmopolites, or cosmopolitan, “a citizen of the world.” Most famously, Diogenes carried a lantern through the marketplace at midday, saying he was searching for an honest man. Once, Alexander the Great came to visit Diogenes while he was lying in the sun, perhaps getting a tan. “Get out of here,” Diogenes said, “you’re blocking my light.”

It is here, at the origin of what we think of as Western society, that we find kynicism as society’s opposite. Diogenes’s father, according to legend, was a manufacturer of coins, but Diogenes, perhaps instructed by the Oracle of Delphi, smashed and defaced them. When invited to a wealthy man’s house and cautioned not to spit anywhere—the kynics were famous for relieving themselves wherever and whenever—he spat in the owner’s face, saying, “I can find no more appropriate receptacle.” We can almost hear Johnny Rotten howling, in 1977, “I am the Antichrist, I am an anarchist.”

A certain kind of highly cultivated white privilege is not only ‘unbearably funny’ but actually unbearable.

Peter Sloterdijk, the German philosopher who began as a Nietzsche scholar before going on to write his epochal 1983 Critique of Cynical Reason, puts it this way: “We could not picture [Diogenes’s] external appearance today or gain an impression of his effect on the Athenian environment if we did not have the visual instruction of the hippies, freaks, globetrotters, and metropolitan Indians.” Living in a post-Christian world, Sloterdijk says, we’re much better suited to appreciate Diogenes’s radical skepticism and unconventional way of life than were our predecessors of the last thousand years: Diogenes was an ascetic, but a liberated one, not a martyr motivated by a consciousness of guilt or sin. Diogenes, he writes, “could be taken as the original father of the idea of self-help . . . . he was a self-helper by distancing himself from and being ironic about needs for whose satisfaction most people pay with their freedom.”

There is another way, too, in which Diogenes and his heirs became the first avant-garde. They were victims of their own success, split, over the course of a few generations, into camps of true believers who accused the others of selling out. In the early Roman Empire, Sloterdijk writes, “kynicism for the first time had found . . . a truly ideal soil, a situation of flourishing alienation in which it inevitably expanded within all directions”:

Because no one could any longer cherish the illusion that he led his ‘own’ life in this political system, innumerable people had to feel the impulse to reestablish their authority in areas free from the state, namely, in the form of philosophies of life and new religions.

On one hand, there were the cults, the political radicals—the Essenes, the Manichaeans, the Gnostics, the Mithraists, the Christians—who embraced Diogenes’s poverty, his contempt for the state and its corrupt institutions; on the other, there were the writers, the cosmopolites, who inherited his sense of humor, his flair for the theatrical, and his refusal to take any kind of piety seriously. At this juncture, kynicism, in Sloterdijk’s words, diverges “in an existential direction and in a satirical-intellectual direction” and disappears. “Laughing becomes a function of literature, and living remains a deadly serious business.”

The Assyrian essayist and novelist Lucian describes the kynic and apparent Christian convert Peregrinus, who committed suicide by self-immolation at the Olympic Games in 185 C.E.: “If . . . he is so firmly determined to die,” Lucian writes, “why does it have to be by fire and with a pomp fit for a tragedy? What is the point of this way of dying when he could have chosen a thousand other ways?” If we want to locate the birth of modern satire—which is another way of saying the birth of modernity itself—we should, Sloterdijk says, start here: with the ability to look at a burning man and see an ironic gesture, a performance. This is the moment when “critique changes sides.” Lucian, after all, is a professional rhetorician, a wandering artist who makes his living composing humorous speeches on the spot; like the radical kynics and proselytizers of the age, he depends on the whims, the fleeting interest, of the public, and thus, Sloterdijk writes, “he comes down so hard on the kynics because they want the same thing . . . if the kynics are the world despisers of their epoch, Lucian is the despiser of the despisers, the moralist of the moralists.”

But there is more to it than that. In a world not unlike the mid-to-late Roman empire—“a colossal bureaucratic apparatus whose inner and outer workings an individual could not fathom or influence”—contemporary citizens of the West have grown so used to satire, so pre-programmed to roll their eyes at the next item that crosses the news ticker, that they have all become, in Sloterdijk’s terms, not kynics in the lost tradition of Diogenes, but cynics. They have become self-satirists. No longer a commitment to a new way of life, cynicism is a lifestyle, what Sloterdijk calls “enlightened false consciousness”:

Psychologically, present-day cynics can be understood as borderline melancholies, who can keep their symptoms of depression under control and can remaine more or less able to work. Indeed, this is the essential point in modern cynicism: the ability of its bearers to work—in spite of anything that might happen, and especiall, after anything that might happen . . . . For cynics are not dumb, and every now and then they see the nothingness to which everything leads. Their psychic apparatus has become elastic enough to incorporate as a survival factor a permanent doubt about their own activities. They know what they are doing, but they do it because, in the short run, the force of circumstances and the instinct for self-preservation are speaking the same language, and they are telling them that it has to be so. . . . Cynicism . . . is that modernized, unhappy consciousness on which enlightenment has labored both successfully and in vain. Well-off and miserable at the same time, this consciousness no longer feels affected by any critique of ideology; its falseness is already reflexively buffered.

To choose an obvious contemporary example: consider Seinfeld, the show famously conceived by its co-creator, Larry David, as an antidote to the traditional, sentimental sitcom: “no hugging, no learning.” And, we might add, no crying. Perhaps the most troubling thing about the show, if we look at it from this perspective, is that Seinfeld’s characters can exist in a permanent kind of irascible misery (George) or bland, observational exasperation (Jerry and Elaine) or manic obsession with minutiae (Kramer), but they are never capable of feeling actual sadness, for themselves or, by extension, anyone else.

This last point is crucial: while it is not news that cynicism of the Seinfeld variety can be a form of selfishness, or social disengagement, it is also a keen expression of a social relationship, an affirmation of a social order. If we go back and reread Critique of Cynical Reason, beginning with Diogenes, a pattern emerges: both kynics and cynics are likely to be people who live on the periphery of a privileged space, who feel both secure and uncomfortable—secure enough to be uncomfortable. Sloterdijk acknowledges this, at least tacitly, but seems not to consider it worthy of much discussion: he never points out, for example, that Diogenes’s extreme behavior was tolerated, even celebrated, only because he was a free man, an educated and fully endowed citizen of the polis—albeit one from a provincial backwater, a kind of arriviste. A woman, slave, servant, or non-citizen would never have been allowed the same leeway in speech and action, just as a black teenager and elderly black woman would have suffered a fate somewhat different from that of Harold and Maude if they had roamed around northern California in the early 1970s stealing cars, mocking policemen, evading arrest, and defacing public property.

Another way of putting this might be that the cynicism of today is a product of intense, yet diffuse, guilt that has hardened into self-mockery and a kind of pervasive, brittle detachment. In the cynical position, artists feel they are allowed to say and do almost anything they want—to find almost anything funny—as long as they admit that nothing they say, no matter how outrageous, will ever have an effect on the world. And as long as they don’t cry.

Where Did All You Shattered People Come From?

Harold and Maude is an unusual movie because it brings together, to use Sloterdijk’s terms, the cynic and the kynic: Harold, the suicide comedian, “well off and miserable at the same time,” and Maude, who spits on the floor, draws a smile on the statue of the saint, and steals the priest’s car. But what if we bring a dash of cruel realism to the scene and imagine, in a vastly more likely scenario, that Harold had never met Maude? What if, instead, he had endured a few more years staging suicides for his mother and then moved out and entered acting school, or joined Second City, or art school, or film school, or graduate school in philosophy, or, god forbid, in creative writing? It is not difficult to imagine Harold reappearing as Andy Kaufman, Christopher Walken, Wes Anderson, or a disembodied voice in the work of Don DeLillo, David Foster Wallace, or Sam Lipsyte. He would have found work to do.

Which is another way of saying that Harold’s disposition—the frozen, catatonic expression; the flat, measured words; the unswerving bleakness of his voice; the feigned nonchalance or childlike mock-innocence—is everywhere in contemporary American culture. If cynicism and kynicism fought a battle in the 1970s, cynicism won: it produced the culture that Wallace defined in his essay “E Unibus Pluram” as “the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the ‘Oh, how banal.’” It is no surprise that Harold and Maude was celebrated in the 1980s and ’90s: it belongs much less to the Baby Boom than to Generation X.

No longer a commitment to a new way of life, cynicism affirms the social order.

There is another element of Harold’s expression, and the symbolic order surrounding him, that bears mentioning, particularly when we think about cynicism as an expression of, as a relation to, privilege: Harold is extremely white, pallid, almost translucent. The emotionally congealed atmosphere around him—the mansion with its enormous, echoing rooms; his mother’s breezy, patrician noblesse oblige—is a caricature not just of aristocratic privilege but also of whiteness itself.

Is Ashby’s implication—which becomes even more plausible as we survey the rest of his cruelly satirized characters—that there is something inherently sad about being white? This may sound like a crude or reductive question; in fact it is a pressing and important one. Psychological studies and population research tell us that in the United States both the overall white population and its richest income bracket report the highest rates of major depression and depression treatment. Many of these same studies point out that because of the lack of mental health coverage and because of complex social stigmas, scholars don’t know how much depression goes unreported among African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans. But in a sense, talking about demographics misses the point, because our entire conception of what depression is, how it manifests, how it can be contrasted against “normal behavior,” is itself racialized. Depression, as the critic Ann Cvetkovich puts it in the title of her book on the subject, is a “public feeling.” Normative white identity has been publicly identified with depression at least since the era of the man in the gray flannel suit and The Lost Weekend (1945), the revolt against the silent misery of the housewife in The Feminine Mystique (1963), and Ken Kesey’s use of the asylum as allegory in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962). Since the 1980s depression has become so diffuse, so normative, that dysfunction—eating disorders, addictions, co-dependencies, DSM-worthy syndromes, abuse, trauma—dominates many, even most, narratives of white American life.

If we were to make a mosaic of images of white sadness, we would naturally choose obvious, archetypal ones: the kitchen where Sylvia Plath commits suicide; Ally Sheedy, in Goth pancake makeup, crawling across the floor of the school library in The Breakfast Club (1985); Ian Curtis intoning “Love Will Tear Us Apart”; Neddy Merrill, in John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” surfacing from his last swimming pool and finding his entire life swept away. But white sadness in its most pervasive form has no obvious marker or sign. In his essay “Feeling Brown, Feeling Down,” the cultural critic José Muñoz, trying to formulate a description of latinidad, or Latino identity, in the United States—an identity so often stereotyped as “spicy,” overly demonstrative, loud, excessive—puts it this way:

It is not so much that the Latina/o affect performance is so excessive, but that the affetive performance of normative whiteness is minimalist to the point of emotional impoverishment. Whiteness claims affective normativity and neutrality, but for that fantasy to remain in place one must only view it from the vantage point of U.S. cultural and political hegemony. Once we look at whiteness from a racialized perspective, like that of Latinos, it begins to appear to be flat and impoverished. At this moment in history it seems especially important to position whiteness as lack.

It is important to stress that Muñoz is talking about normative whiteness: neither whiteness as pigmentation nor even whiteness as the culturally constructed racial identity we know it to be, but whiteness as an emotional norm that is, in the American context, “neutral,” that Latinos and all others are expected to exhibit. We are all supposed to be lacking, and the sense of lack, as Claudia Rankine puts it in her 2004 book-length poem Don’t Let Me Lonely, is supposed to precede all other identities:

In third-world countries I have felt overwhelmingly American, calcium-rich, privileged, and white. Here, I feel young, lucky, and sad. Sad is one of those words that has given up its life for our country, it’s been a martyr for the American dream, it’s been neutralized, co-opted by our culture to suggest a tinge of discomfort that lasts . . . the time it takes to change a channel. But sadness is real because once it meant something real. It meant dignified, grave; it meant trustworthy; it meant exceptionally bad . . . it meant falling heavily; and it meant of a color: dark. It meant dark in color, to darken. It meant me. I felt sad.

Over the last two decades, critics such as Cvetkovich and Lauren Berlant—pioneers of the subfield of literary studies known as affect theory—have begun to link this pervasive sense of emotional vacancy to what Cvetkovich calls the “crushing pressures” of contemporary life in a capitalist economy. “Why,” Berlant asks in her 2011 book Cruel Optimism,

do people stay attached to conventional good-life fantasies—say, of enduring reciprocity in couples, families, political systems, institutions, markets, and at work—when the evidence of their instability, fragility and dear cost abounds? . . . What happens when those fantasies start to fray—depression, dissociation, pragmatism, cynicism, optimism, activism, or an incoherent mash?

To inhabit a state of cruel optimism, Berlant says, is to be caught within a network of “dissolving assurances” where the thing that “ignites a sense of possibility actually makes it impossible to attain.” The result is a kind of lived minimalism, a depressive stasis that could be called “coping”: “when the ordinary becomes a landfill for overwhelming and impending crises of life-building and expectation whose sheer volume so threatens what it has meant to ‘have a life’ that adjustment seems like an accomplishment.”

We might bring up, at this juncture, an unacceptably simple question, a question so simple that Diogenes himself might have asked it: What does it mean to have a life? What does it mean to have a good life? We tend to frame this question entirely in individual terms. A good life means a rewarding job; satisfying romance; material success; security; stable, well-adjusted, high-performing children. What happens when we ask whether a good life—an actually happy life—is possible without observable justice or reconciliation in the world?

In Ashby’s first movie, The Landlord—made in 1970, just before Harold and Maude—Beau Bridges plays Elgar, a grinning, sheepish, oblivious scion of a wealthy WASP family. Insisting that “everyone wants his own home,” he buys a brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, then an impoverished black neighborhood, with the intention of gutting the building and turning it into a showcase for a “huge psychedelic sculpture.” His tenants, not surprisingly, have other plans: they refuse to be evicted, harassing and humiliating him at every turn. Just when we expect Elgar to flee the scene or fight back in slapstick fashion, he instead falls in love: first with Lanie, a light-skinned black woman who lives in the neighborhood, then with Fanny, one of his tenants. Things go disastrously wrong—Fanny has Elgar’s baby, then rejects it; her boyfriend attacks Elgar with an ax—but the movie resists tragedy, and the tragic mulatto: Elgar keeps the baby and reconciles with Lanie.

Harold and Maude survived its disastrous release and became iconic; The Landlord disappeared. An internal film company document, now available online, notes dryly, “At the time [it] was programmed, unrealistic optimism about the potential audience for this type of film prevailed.” (It was finally released on DVD in the mid-2000s.) Bu t if we watch one film with an intimate knowledge of the other, it is impossible to see them as anything but a diptych. The Landlord makes explicit whatHarold and Maude only implies: these are movies in which a certain kind of highly cultivated, ossified white privilege is not only “unbearably funny” but actually unbearable, and the only alternative is not just escape—escape is too easy, too obvious—but a kind of breaking of the frame of comedy itself.

There is enormous pressure on narratives of privileged sadness—whether they start funny or not—to end in tragedy and self-destruction. In Western culture this trajectory begins at least with Hamlet and The Sorrows of Young Werther and extends all the way to the fourth- or fifth-generation emo bands of today, whose not-entirely-ironic names include I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness and The World is a Beautiful Place and I Am No Longer Afraid To Die. (The title of this section, “where did all you shattered people come from?” is from a song by the emo band Sideshow. When I first heard it, in my early twenties, it seemed to me a purely rhetorical question. Not until many years later did it occur to me that the answer might not be so obvious.) When Ashby freezes the frame as Harold’s Jaguar plunges off the cliff, that trajectory reverses itself. Not so much light, but lightness, floods in. We begin to see the depressive logic of permanent sadness as a thought that can be undone.

Bas Jan Ader, a Dutch performance artist active in Los Angeles, made a short film of himself crying, I’m too sad to tell you, in 1970. In the movie, no reason is given for his sadness; although it is obviously a performance, it is not a parody, not played for laughs. Five years later, Ader performed his last work, In Search of the Miraculous, by boarding a small boat in Cape Cod with the aim of sailing to England. His boat was later found, off the coast of Ireland, but he was never seen again. Of course, it is possible to “read” Ader’s presumed death as fulfillment of the familiar narrative of privileged self-destruction, just as Harold’s death could be a new kind of escape, an extension of his impunity. But it is also possible to see In Search of the Miraculous as an expression of what can happen when a privileged artist—a white artist—tries to imagine life on the other side of sadness, when sadness is no longer our material. Ader, and Harold, wander out of the frame, playing banjos, singing sea shanties. Is that enough?

What Is This Jazz?

Lorrie Moore’s Anagrams, published in 1986, follows the unraveling of Benna Carpenter, a young woman whose life is recounted, or reconstituted, in several different ways—as a nightclub singer, a young wife and homemaker, and an adjunct college professor. In another novel these multiple pathways might make for a dissonant, fragmentary text, but in Anagrams we hardly notice them, because Benna’s voice—a mixture of mordant self-pity, lacerating self-criticism, and a constant, puckish drumbeat of jokes, puns, witticisms, and cutting analogies—never varies:

Basically, I realized, I was living in that awful stage of life from the age of twenty-six to thirty-seven known as stupidity. It’s when you don’t know anything, not even as much as you did when you were younger, and you don’t even have a philosophy about all the things you don’t know, the way you did when you were twenty or would again when you were thirty-eight. Nonetheless you tried things out: ‘Love is the cultural exchange program of futility and eroticism,’ I said. And Eleanor would say, ‘Oh, how cynical can you get,’ meaning not nearly cynical enough. I had made it sound dreadful but somehow fair, like a sleepaway camp. ‘Being in love with Gerard is like sleeping in the middle of the freeway,’ I tried.

‘Thatta girl,’ said Eleanor. ‘Much better.’

Anyone who knows Lorrie Moore’s later work will recognize this voice instantly. Benna is a rawer, more immature version of her better-known characters: the manic mother of “People Like That Are the Only People Here,” the wildly acerbic Zoë Hendricks of “You’re Ugly, Too.” Benna, like so many of Moore’s protagonists, is locked within the double bind Berlant describes in Cruel Optimism, where “adjustment seems like an accomplishment.” (In fact, as Moore’s book proceeds, we see that her “adjustment” is itself a fiction: the child she describes so vividly is an invention she uses as a coping mechanism.) But it is important not to undervalue her optimism, the sometimes-furtive way she demonstrates, and simultaneously undermines, a capacity and desire for love. Though she has an on-again, off-again boyfriend, the sad-sack wannabe opera singer Gerard, the focus of her desire turns out to be Darrel, a black Vietnam veteran and student in her creative writing class:

He told her a long, complicated story about an officer’s party in Saigon, where he’d hurled a bottle of cognac against the wal and stomped out imperially. And though she didn’t catch exactly why he’d done it, she could imagine this tall, strong man, capable of such astonishing gestures, such huge moments, such moral angers. He also told her he wanted to be a dentist.

‘A dentist,’ she repeated dumbly, and her tongue fished back into her molars for crumbs, for the rot-nuggets of cavities.

‘Probably an orthodontist.’ He grinned. He had perfect teeth. As a kid, growing up in a trailer in Tomaston, she had nightly pressed her front teeth hard against the heel of her hand, to push them back: orthodontia for the poor and trailered.

‘Braces,’ she said.

‘Yeah,’ and he smiled like a king.

The political term for an encounter such as this is “intersectionality”: two systems of oppression—in this case, poverty and racism—or struggles against oppression seem to be squarely in opposition, or even competition, unless we can grasp the inherent link between them. In this case, if there is an intersection, it’s a blind one. As smart, skeptical, and detached as she is, Benna can’t, or won’t, analyze her feelings for Darrel.

At this point we might expect Moore to expel him from the story, the way black characters are so often expelled from white American fiction: as potent, glimpsed figures of moral authority or emblems of a characters’ bad conscience, but always as what Henry James called the ficelle, an instrumental figure with no central dramatic significance. But, to Moore’s everlasting credit, Benna stays stubbornly attached to Darrel, grappling with a churning mixture of resentment, inferiority, and almost fetishistic desire:

Where are Darrel’s sneakers? He is wearing what my brother Louis used to call “hard shoes”—leather shoes. And a slick shirt, slippery and nice. It has a dry, sweet smell, like bubblegum and cedar. Whenever I have danced this way with Gerard, it’s always been sort of a joke: I lead and he pretends to swoon. With Darrel, there’s no joking . . . .

I turn back, look up at Darrel, and feel my heart fluttering. It’s a Tennessee Williams heart. A bad Tennessee Williams heart. I don’t know what to say. The music urges love on you like food . . . . What is this jazz? I grew up in the country, in a trailer. We did things like stand far apart and ripple our stomachs in and out.

Darrel is too good for Benna to turn away from, in every way that Gerard isn’t: he’s earnest, sensual, a talented poet with aspirations for a stable future. When they have sex, Benna thinks, “I know if I can keep feeling like this I’ll be okay, if I can feel like this I’m not dead, I won’t die. Life is sad. Here is someone.” But the desperation of her need for him is also, transparently, a refusal to take him seriously; after a few months of intense intimacy, their relationship implodes in a breakup scene worth quoting at length:

Here we are on the god-knows-what anniversary of John Lennon’s death and Darrel is saying he wants to be an orthodontist. Maybe I am hearing things wrong. This sometimes happens this time of year: People hear things wrong. The night John Lennon died I was standing in a deli and someone burst in and shouted, ‘Guess who’s been shot? Jack Lemmon!’ . . . Darrel has meant something else all along. Surely he doesn’t want to become a jeweler of teeth, a bruiser of gums. It’s a joke. ‘Yeah, right,’ I laugh. ‘I can see you as an orthodontist.’

Darrel looks suddenly irritated, screws up his leathery face into a fist, bunched like one of those soft handbags ‘What, isn’t that good enough for you, Benna? Upward mobility for the oppressed? Is that just not angry enough for you?’

It’s true. That’s what I want for Darrel, from Darrel. He should be angry like Huey Newton. Or in a wheelchair making speeches, like Jon Voight.

‘You want me to be a little black boy vet with a PhD and a lot of pissed-off poetry?’

‘Why not?’ I say. It doesn’t sound bad, it’s just the way he’s saying it.

Darrel stands up and paces peevedly about the living room.

‘I can’t believe it. You’re just like everyone else. You want me to be your little cultural artifact. Like a Fresh-Air child. Come off it, Benna.’

‘You come off it,’ I say. This is the old children’s strategy of retort. I’ve learned it from Georgianne or remembered it or simply saved and practiced it. ‘You’re being so, well . . . bourgeois.’

This is the word that intelligent, twentieth-century adults use when they want to criticize each other. It is the thinking man’s insult. It is the wrong word. Don’t let your mouth write a check your ass can’t cash, Darrel said once, and this time I truly have. Darrel’s been storing up for it and leaps on it like a wild man. ‘Bourgeois!?’ He’s pacing quick and hard, left to right. ‘You!’ he shouts, freezes, points to me.

It is here that the sterile tent of ironic defensiveness, the imprimatur of cynical cool, the reflexive habit of turning tragedy into verbal junk that Benna has maintained her entire life, is finally breached: John Lennon may be Jack Lemmon, but Huey Newton, somehow, is still Huey Newton. For her, Darrel is not just an emblem of psychological health and sexual healing; he represents an entirely different order of redemption as well. Darrel, on the other hand, can take a joke, but he can’t ironize away his desire for a solid income, a professional career, the terminally uncool, unexceptional, bourgeois life Benna has till now mocked so relentlessly as a way of inoculating herself against the shame of downward mobility.

It would be an understatement to say that moments such as this—moments of honest confrontation between black and white characters, when all the cards, economic, racial, lustful, are on the table—are rare in American fiction. When they come, they tend to evaporate so quickly that we wonder if they happened at all. When Benna has lost Darrel, her life plunges swiftly toward rock bottom: she loses her precarious teaching job, and Gerard dies in a freak accident. In the novel’s final moments, utterly bereft, observing Georgianna, her imaginary daughter, Benna thinks again, “Life is sad. Here is someone”—as if to say, as if we didn’t know, that Darrel is this fiction’s fiction, or, more precisely, this fiction’s fantasy, its object of cruel optimism, the object that, when desired, becomes impossible to attain.

I Guess We Already Knew That, But Still

At one point in Anagrams, when Benna and Darrel’s romance has just begun to disintegrate, Benna challenges her class to write a group sestina, using the words “race,” “white,” “erotics,” “lost,” “need,” “love,” and “leave.” Darrel, from the back of the room, observes that this is seven words, not six, and Benna, “putting her hands on her hips, a gesture of nonplussed authority,” first erases “love,” then changes her mind and erases “white.” It is a poignant, and pregnant, gesture, but one that goes nowhere: Benna stares out the window, suddenly bored by her own assignment, chews her cuticles, says to herself, “Men are outrageous,” and there the scene cuts off, leaving the sestina—to which Darrel himself, presumably, contributes—to our imagination.

What are we to make of the way race figures one moment as something alive, frightening, and intimate, and the next—with the word “white” erased but still present, hovering at the margins, chosen to be unchosen—as a subject that is boring, unbearable, predictable, an object of ridicule? A Gate At The Stairs (2010), Moore’s third and most recent novel, takes this question as a central theme. There are two, or more, interracial romances at the center of the narrative. Tassie Keltjin, the narrator, is a white college student hired by a white couple as a nanny for their newly adopted, biracial daughter, Emmie. Roughly at the same moment, Tassie falls in love with a dark-skinned Brazilian classmate, Reynaldo. Emmie’s adoptive mother, Sarah, is a quintessential Lorrie Moore heroine—anxious, neurotic, acerbic, given to flashes of mordant humor and flights of manic, righteous anger—who organizes a weekly “support group” for multiracial families in their Midwestern college town (a stand-in for Madison, Wisconsin, where Moore lived and taught for twenty years). Tassie, assigned to supervise the children, hears the adults’ conversation from the top of the stairs, or through half-closed doors. It is not conversation, really, but blasted slogans, denunciations, expressions of guilt, self-doubt, recrimination, and outright rage:

‘. . . institutionalized bigotry can subtly convince you of its rightness. With its absurdity removed, its evil can compel . . .’

‘And even the adults pat the hair as if it’s the funniest thing they’ve ever seen on a mammal . . . and of course available for public patting, like a goat in a zoo . . .’

‘Of course homework is just a measure of the home! And so the kids of color will always fall behind . . .’

‘The African-American peer group is the strongest and the Asian-American is the weakest—that is, Asian-American parents have power that the African-American parents do not.’

‘School is white. And school is female. So it’s the boys of color who have the hardest time, and if they’re not into sports the gangs will lure them in . . .’

‘I guess we already knew that, but still.’

It is tempting to compare these scenes to the moment in Do The Right Thing (1989) when Spike Lee has each character, in turn, tell the camera exactly what he or she thinks of Italians, white yuppies, Korean shopkeepers, Puerto Ricans, or Radio Raheem, but as Moore produces it, it is precisely the opposite: anonymous, passive, self-righteous, self-flattering, and with no end in sight. Not a healthy venting or purging of animosity but an autoimmune condition, the body of “enlightened” liberalism attacking itself. As Tassie says, these are “bull sessions,” and the whole enterprise turns out to be a fraud: Sarah and her husband Edward are revealed to be not childless parents but parents who years before caused the death of their own son; Reynaldo is not Brazilian but a wannabe jihadist from Hoboken using an assumed name; and Emmie, when Sarah and Edward abruptly split up, is repossessed by the foster system.

What is so terrifying, and terrifyingly accurate, about Moore’s fiction can be summed up in Sloterdijk’s phrase: “reflexively buffered.” Whether we call it cynicism, melancholy, depression, or simply sadness, we are talking about a state that maintains itself through satire, in which the buffering, the emotional distancing, is assumed to be continuous, from character to narrator to text to reader. We are not, under any circumstances, supposed to take her characters’ highest aspirations seriously.

But what if we do?

Autoimmune conditions are notoriously difficult to treat, but in most cases not fatal; sometimes they require a holistic approach, acupuncture, complementary medicine, and so on. They often induce—and no researcher seems to know why—a feeling of helplessness, a fog of isolation and self-recrimination, that seems permanent but doesn’t have to be. What if there were a way to write this same cultural condition but treat fatalism as a symptom rather than a prognosis? At this point we may hear Darrel’s voice saying, via Benna, “Don’t let your mouth write a check your ass can’t cash.” But why should we assume—not for the purposes of Moore’s celebrated career, but for the many writers who follow in her wake—that there is no such check, and no way for our asses to cash it?

One Comes To Feel the Absurdity of Life

In “The Niggar Family,” a skit that appeared on Chappelle’s Show in 2004, Dave Chappelle creates a Leave It To Beaver–style black and white sitcom about a white family whose name happens to be Niggar. Their dialogue is saturated with racial insults displaced by an accident of American pronunciation: “Niggar lips,” “he’s one lazy Niggar,” “Niggar rich.” Racism, and the word “nigger,” still exist in this universe, resulting in much comic confusion: at one point, Chappelle and his date realize that the maitre d’ in a fancy restaurant was saying, “Niggar, party of two,” referring to the white couple standing next to them, which results in strained, awkward guffaws all around, after which Chappelle, still laughing, says to no one in particular, “This racism is killing me.”

What happens when racism becomes a joke white and black people are supposed to share? In a society as ostensibly polarized as ours—particularly when viewed from the perspective of the hair-trigger sensitivity about race Lorrie Moore’s characters display, what some commentators have recently called “white fragility”—it seems impossible to imagine such a thing happening, but of course it does, all the time. Our cultural moment is particularly saturated with racial satire, often produced by comedians of color, from Hannibal Buress to Key & Peele to Margaret Cho, but anyone familiar with the history of black American comedy—Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy, Richard Pryor, Dick Gregory, back to the rich and complicated legacy of love and theft in blackface and minstrelsy—can recognize that the taboo-breaking, cringe-inducing, uneasy laughter of “The Niggar Family” is not new.

Which doesn’t make it any less strange, or fraught, or coded. How could it not be, when the barely suppressed violence of a supremacist culture is out in the open? Black and brown writers and performers, one conventional argument goes, are permitted, indeed expected, to make racism their explicit material; white writers can have guilt, anxiety, and self-doubt instead. If we laugh at the same material, it is only because the joke functions as a double entendre—something that can be understood twice. Richard Pryor puts it this way, on the album Craps, recorded in 1971: “It’s great to think that we can all sit in the same club together, white and black, and not understand each other. It’s amazing—it can only happen in America.”

Chappelle, famously, was not okay with that. He spent much of his childhood—and still lives today—in Yellow Springs, Ohio, a college town not unlike Moore’s Madison; his parents were both academics, and, as he once noted in an interview, he is the first member of his family not to go to college—a line Moore might have written. In skits such as “The Mad Real World” and “Tyrone Biggum’s Fear Factor,” Chappelle’s Show is exquisitely, intimately attuned to the fragility of well-meaning white liberals and self-flattering intellectuals. In the show’s most joyful and uncontained moments, Chappelle engages in a kind of unapologetically liberal, equal-opportunity, integrationist comedy: watch the skit “Dancing for Different Cultures,” in which Chappelle brings together John Mayer, Questlove, and a salsa pianist named Sanchez to demonstrate that white people, black people, and Latinos will dance uncontrollably if exposed to guitar riffs, hip-hop beats, or congas.

The radicalism of Chappelle’s comedy, we might say, lies in just this kind of intimacy and plasticity—a refusal to remain within one comic tradition or sensibility, a refusal to let his audience stay within the bunkers of the double entendre. But this radicalism also gave Chappelle’s Show its own fragility. It was his perception that white audiences were misinterpreting his caricatures, reveling in his parodies of characters such as Tyrone Biggums, that made him cancel the show at its moment of greatest success. In June of 2004, he walked off the stage at a concert in Sacramento, saying, “You know why my show is good? Because the network officials say you’re not smart enough to get what I’m doing, and every day I fight for you. I tell them how smart you are. Turns out, I was wrong. You people are stupid.” Less than a year later, he fled to South Africa, announcing, among other things, “I have to check my intentions.”

And exactly what were his intentions? In a 2013 essay for The Believer, Rachel Kaadzi Gansah describes her trip to Yellow Springs in search of an interview with Chappelle, who has spoken only briefly, and elliptically, about his reasons for leaving comedy in 2005. Although she manages to speak to his writing partner and several other associates, Chappelle remains steadfastly silent. Finally, in a deft act of writerly frustration, Gansah turns to the elder statesman of black comedy, Dick Gregory, for his interpretation of Chappelle’s career. Gregory, who in recent years has become something of a conspiracy buff and professional crank, is quite gentle in his assessment of Chappelle—“I wish I could have thought of that”—and almost as an afterthought, offers his own definition of comedy:

When I suggest to Gregory that he used his comedy as a weapon, he shouts, ‘What?’ so loud I get scared. ‘How could comedy be a weapon? Comedy has got to be funny. Comedy can’t be no damn weapon. Comedy is just disappointment within a friendly relation.’

What would it take to establish a friendly relation, a shared impulse to laugh, among an audience as varied as the American audience—the audience that, in theory, at least, watches Chappelle’s Show after Seinfeld after Girls, that reads Lorrie Moore but also Colson Whitehead and Junot Díaz, the audience that lined up for hours to see Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, a giant black female sphinx made of sugar in the Domino factory in Brooklyn? “A remark appears witty when we impute a psychologically necessary significance to it, but even when we are doing so, promptly deny it,” Freud says in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. “The basis for our feeling of comedy consists in our immediate transition from lending sense, accepting as true, granting meaning, to our consciousness or impression of relative nothingness.” Freud, like Sloterdijk, assumes that within a given cultural matrix there is only one first-person plural; but here, now, in this time and place, we are haunted—in comedy as in so many other ways—by the absence of a “we.” It is much easier to view Harold’s struggle against his own privileged misery—the struggle between cynicism and kynicism—as the private, idiosyncratic, comic language of whiteness, and to see Chappelle’s work, or Pryor’s, or Kara Walker’s, as existing purely within a black comic tradition that has its own hard-won privacy and exclusivity, than it is to ask: Is laughter itself doing some work we don’t yet recognize? Or, to put it another way, does comedy affirm what we already think we know and who we already think we are, or can it enlarge what we know, and who we think we are?

“Racism introduces absurdity into the human condition,” Chester Himes wrote in his autobiography: “Not only does racism express the absurdity of the racists, but it generates absurdity in the victims. And the absurdity of the victims intensifies the absurdity of the racists, ad infinitum. If one lives in a country where racism is held valid and practiced in all ways of life, eventually, no matter whether one is a racist or a victim, one comes to feel the absurdity of life.” In “The Niggar Family,” the homophonic vowel, the identity of “a” and “e,” cuts across the entire history of racism, making it a category mistake. It takes on a kind of cosmopolitan, kynical, Diogenesian madness. The joke, and the violence it describes, are inseparable, but somehow still worth laughing about because we are all implicated in it. How much misery have we experienced, maintaining this way of life? How can we be reconciled to it? How could we not say, how could we not see, that it’s killing every one of us?

Cave Canem

At the end of “E Unibus Pluram,” originally published in 1993, David Foster Wallace predicted that the age of irony was nearly over: “The old postmodern insurgents,” he writes, “risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship . . . . Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk . . . . accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness.” He returned to this theme in his famous 2005 speech to the graduates of Kenyon College, “This is Water”: “If you really learn how to pay attention . . . . it will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars.”

It was supposed to happen after the end of the Cold War; after September 11th; after the death of the hipster; after the Generation Xers grew up, had babies, and moved to the suburbs; after Obama’s election; after the Great Recession; after Occupy: the death of irony and the birth of the “New Sincerity,” a term that cultural critics and trend-spotters discuss but which has never quite taken hold. The New Sincerity—like so many things heralded as “New,” in capital letters—is as much a product of the white cultural imagination as the cynicism and irony that preceded it. In the articles I can find that use the term, virtually all the touchstones (Wes Anderson, Cat Power, Daniel Johnston, Michael Chabon, Miranda July) are white, and the common thread among them, if there is one, is not sincerity but highly cultivated, stylized forms of adolescent and pre-adolescent play replicated in adulthood. It is not for nothing that Anderson’s first major movie, Rushmore (1998), is a more-or-less explicit homage to Harold and Maude, without the Maude, or that at least one essayist replaced the word “Sincerity” in “New Sincerity” with “childishness.” These artists, for the most part, identify not with insurgency, rebellion, or even satire as such, but with private, hermetic, imagined worlds—what Freud called the “impression of relative nothingness”—that often have the effect of making the actual world disappear.

One limit of cynicism, we might say, is this kind of emotional disengagement, which often reads like regression. Another is a particular kind of disembodied and thoroughly serious artistic rage: the joke that is intended to provoke violence. A cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed published in the face of death threats that are—sooner or later—likely to be carried out, a movie about the assassination of a North Korean dictator that names the actual dictator in question. Arguments about freedom of expression, necessary as they are, tend to obscure another aspect of these works: by taking comedy to its furthest extreme, to the point where the work provokes not only adversarial violence but state violence in response—what we might call weaponized comedy—these artists engender a kind of solidarity, the catharsis, cohesion, and elation of a mass audience, that they could find no other way. As Morrissey put it: if it’s not love, then it’s the bomb that will bring us together.

Is it possible, when we look at the escapist tropes that dominate so much white American comedy and satire, to talk at all about intersectionality, about the “friendly relation,” the elusive audience that, in laughing, actually understands the same joke? It may not be. To place Harold and Maude and Lorrie Moore next to Spike Lee, let alone Dave Chappelle, may just be an egregious category mistake. But the alternative—which we all practice, every day, sometimes passively, sometimes as principle—is to go on pretending, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that we speak private languages that never overlap. It is to pretend that there is no way of describing—as Anagrams and The Landlord and Chappelle’s Show describe—how we suffer together, if not as one. When Walker was challenged about the audience response to A Subtlety, which included obscene gestures and selfies widely interpreted as racist, she responded with a film, An Audience, which captures a racially mixed crowd responding to her gigantic sugar pseudo-monument in almost every conceivable way: with laughter and tenderness, vulgar remarks, and inscrutable silence. There is no way to calibrate, or predict, the responses. “Human behavior,” Walker said, “is so mucky and violent and messed up and inappropriate. And I think my work draws on that. It comes from there.”

In Colson Whitehead’s novel Apex Hides the Hurt (2006), the unnamed protagonist, a young, black branding consultant for a major advertising firm, is hired to choose a name for a small Midwestern town that has split into three political camps: entrepreneurs, who want to rename the town New Prospera; descendents of the town’s dominant family, who want to keep the name Winthrop; and descendents of the town’s original black residents, who want to restore the long-discarded original name, Freedom. Whitehead’s consultant is an embodiment of Sloterdijk’s definition of contemporary cynicism—able to work under any circumstances, happy to embrace the vacuousness of his profession, while silently satirizing it at every turn—who made his reputation by rebranding a down-market bandage as Apex, available in a variety of flesh-tones to “hide the hurt.” But when he applies an Apex bandage to his injured toe, it becomes hideously infected and has to be amputated. In pain, physically compromised for the first time, he chooses a new name for the town, deposits it with his clients in an envelope, and leaves before they have time to react: Struggle. “He heard the conversations they will have,” Whitehead writes, “They will say: I was born in Struggle. I live in Struggle and come from Struggle.”

Are we supposed to laugh? Or feel that something has actually changed? In this moment, the veil of cynicism lifts: we are not stuck in the endgame, the telos, of failure but returned to the vivid present as our protagonist wanders out of the frame. “There had been a moment . . . when he thought he might be cured. Rid of that persistent mind-body problem. That if he did something, took action, the hex might come off. . . . As the weeks went on and he settled into his new life, he had to admit that actually, his foot hurt more than ever.” Is it enough? It may never be. Can any of us fully say that we have snapped out of our illusions? On the other hand, Whitehead seems to be saying, if we can give our suffering a name, a source, a trajectory, we can also imagine its ending. As if in the end all this pain might amount to something.

This essay originally appeared in print in the May/June 2015 issue. Boston Review is nonprofit and relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate here.