I Love Artists: New and Selected Poems

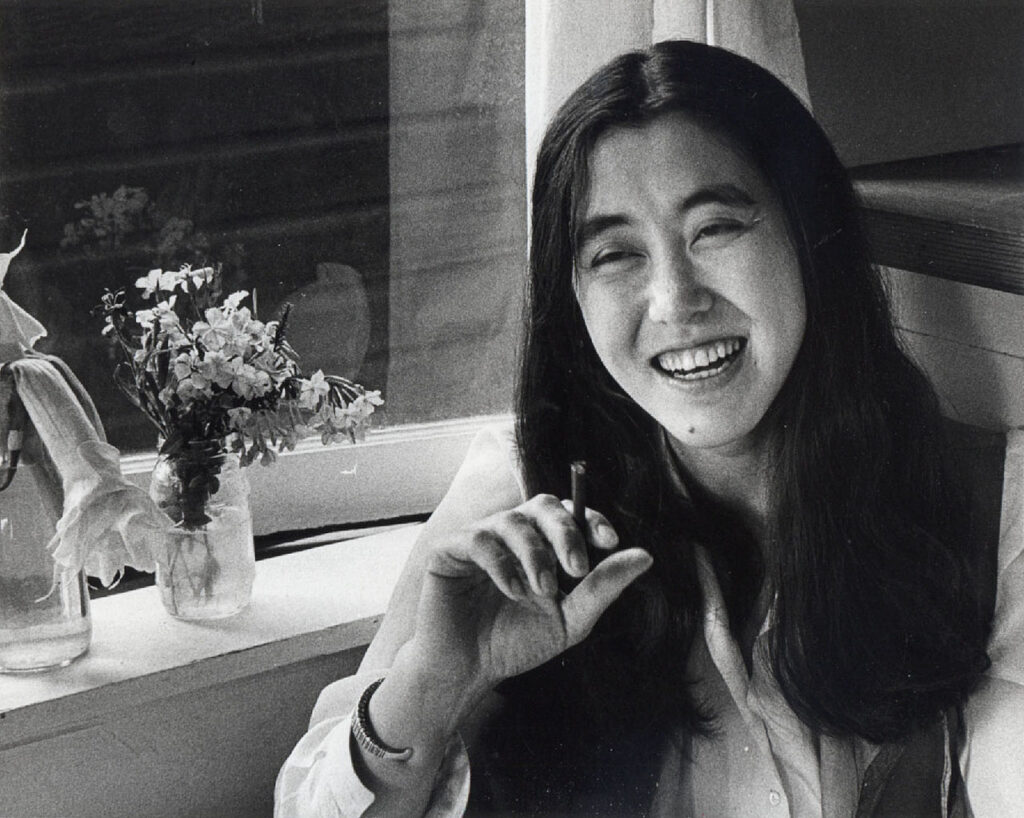

Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge

University of California Press, $19.95 (cloth)

Though the publication of Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge’s selected poems marks a seminal point in her career, Berssenbrugge’s name still remains unfamiliar to many readers of contemporary poetry. Born in Beijing in 1947 to a Chinese mathematician and an American-European scholar of Far Eastern studies, Berssenbrugge grew up in Massachusetts, studied at Barnard and Reed Colleges, earned an MFA from Columbia in 1973, and then moved to New Mexico, where she became a self-described hermit. Her work has been published heretofore only in limited editions from small presses, including Kelsey St. and Burning Deck. For a clue about her work, we might turn to the following lines from her poem “Fog”:

She can describe for you the phenomenon of feeling her way through the fog. For whom does she describe this?

What ignorance can her description eliminate?

Which person is supposed to understand her description, people who have been lost in fog before, or people who have lived on the desert and never seen what she would describe?

These lines show Berssenbrugge to be a poet who favors the horizontality of long lines, the breathing room of white space, and prose-like cadences. She is a poet concerned with phenomena, natural and existential, and with thought, representation, audience, and forms of communication. One might also suppose that she is an expository poet, methodical in the construction of an argument, perhaps even didactic, but this would be off target. If some of Berssenbrugge’s poems read like proofs, it is not because of their logic but because of their abstraction, their theoretical tone.

Berssenbrugge’s poems masquerade as theoretical treatises, but they are really conceptual collages. In fact, fog, a natural phenomenon that obscures, transforms, and abstracts familiar objects and surroundings, is the ideal prop for Berssenbrugge the magician. She is a Mondrian in verse who takes single concepts—empathy, hearing, endocrinology (all titles of her poems)—and builds a poem through webs, grids, nets, concordances, and continuums. In “Concordance,” one of the new poems in I Love Artists, she writes,

Writing encounters one who does not write and I don’t try for him, but face-to-face draw you onto a line or flight like a break that may be extended, the way milkweed filling space above the field is “like” reading.

Then, it’s possible to undo misunderstanding from inside by tracing the flights or thread of empty space running through things, even a relation that’s concordant.

Seeds disperse in summer air.

When Berssenbrugge writes “face-to-face”— revealing her own face and seeking out her reader’s— she is enchanting. You want her to write for you, not for the “him” on the sidelines. You want to receive all that she has to offer, like the speaker of “Red Quiet,” another new poem, which begins: “I look into his eyes and feel my awareness expand to contain what he will tell me, as if what he says is a photograph of landscape and in my mind will be a painting of ‘Hill,’ ‘ Part of the Cliffs,’ ‘ Purple Hills.’ ” This new selection of Berssenbrugge’s work is exciting not merely because it gives many readers their first glimpse of an impressive poet but also because it allows those who may have read her piecemeal over the years to trace how she has come to write her most expansive, most stirring poems to date.

In addition to being a good introduction to Berssenbrugge’s work, I Love Artists is a record of her development, beginning with two poems from her first collection, Summits Move with the Tide (1974). These poems, “Aegean” and “Perpetual Motion,” demonstrate that landscape, light, and color—elements that align Berssenbrugge’s work so closely with visual art—are her great subjects from the very beginning. Yet unlike the characteristically long, prose-like lines she later developed, in these early poems her form is pared down, sparse, composed of two- or three-beat, haiku-like utterances, as we see in the second section of “Perpetual Motion”:

I touch your face

of rosewood and sap

the last vanished yellow

of sunset on the mountain

the first cellular light of a flank.

The voice lacks affect, as if the mountain itself were speaking, and the “cellular” quality of the light is the first sign of Berssenbrugge’s lasting engagement with scientific terminology, complicating aesthetic descriptions of the natural world by employing language from other fields, such as biology or physiology.

The poems from Berssenbrugge’s second book, Random Possession (1979), then experiment with a first-person perspective and extended narrative. These poems are more personal than the earliest poems in the sense that the speaker behind the observations is no longer invisible, but has become an actor in the drama of the landscape being described. Thus the poems’ subject shifts from mere landscape to landscape self-consciously perceived. For this poet, it is a crucial development, opening up the questions of perception and representation that are Berssenbrugge’s main preoccupations. It is like the difference between a pastoral landscape by Corot, one of those exquisite studies of light, and a landscape by Van Gogh, or, more accurately for this poet’s geography, Georgia O’Keeffe, an associate of Berssenbrugge’s during her first years in New Mexico. In “The Field for Blue Corn,” Berssenbrugge writes: “I learned the palette / of diffuse days. Positive tones, finely altered / are silence and distance. In curtained rooms / a pulse beats in prisms on the floor / Other days one goes out adorned and sunburnt.”

Reading these poems is a lesson in synesthesia, the translation of the perceptions or measurements of one sense into the terms of another—sight into sound, touch into sight: “As with / land, one gets a sense of the variations / though infinite, and learns to make references.” Here is the beginning of Berssenbrugge’s extended phenomenology of perception. Taking cues from such philosophical precursors as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Berssenbrugge’s aesthetic study is also concerned with “attention” and “judgment,” sensation as a unit of experience,” the body as object,” the experience of the body,” and especially “the spatiality of one’s own body and motility.” This phenomenological framework is the ground from which Berssenbrugge’s forays into the New Mexican landscape begin.

One such foray is recounted in The Heat Bird (1983), Berssenbrugge’s third book, a long poem divided into a series of single stanzas. Like Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” The Heat Bird is an experiment in seriality and perspective. The poem opens with the speaker tracking a big bird: “I walk into the meadow to find what I’ve already called / an eagle to myself”; following the disappearing bird, she stumbles unexpectedly on the decomposing carcass of a cow. While coldly monitoring the process of decomposition over days and weeks, the poem also records an unrelated but concordant accretion of desire in the speaker:

When I touch your skin or hear singers in the dark, I get

so electric, it must be my whole absence pushing

I think, which might finally flow through proper canyons

leaving the big floor emptied of sea, empty again

where there used to be no lights after dark.

Such opposing energies provide the series with alternating diminuendos and crescendos of emotion, building the tension that propels the long poem and begs for resolution. Berssenbrugge resists this resolution, ending suddenly with the ambiguous sentence, “If a bright clearing will form suddenly, we will / already know of it.” Berssenbrugge’s heat bird is like Kandinsky’s series of horse-and-rider paintings before he fully embraced non-objectivity: a dubious figure gradually loses definition, something traceable by symbol eventually breaking free of reference.

I Love Artists makes this trajectory towards non-objectivity clear, and by Empathy, Berssenbrugge’s poems have severed most of their ties to the objective world. Though her titles refer ostensibly to things or places—fog, the Alakanak precinct of Alaska, Texas, Tan Tien, a swan—the poems use these markers mainly as points of departure for extended meditations. Returning to where we began, the poem “Fog,” we find lines that both describe and enact the growing abstraction and intention of Bersenbrugge’s poems in general:

Paths of energy were forced to stay in the present moment by being free of reference, making it impossible to focus on two things at once, and showing by its quietness that energy of attention is as much a source of value and of turbulence as energy of emotion.

Over the next decade-plus, from 1989 to 2003 (when Nest was published), Berssenbrugge would develop her style of pushing long lines, interrupting subject and attention, and interspersing abstract or theoretical language among concrete references. As the speaker of “Texas” says, revealingly: “I used the table as a reference and just did things from there / in register, to play a form of feeling out to the end.”

Writing a poem with the intention of “playing a form of feeling out to the end” means for Berssenbrugge incorporating still more languages and arts into her poems, as Endocrinology, her art-book collaboration with Kiki Smith, demonstrated in 1997. Unfortunately, only the text of this work is reproduced in the current volume, a limitation that impoverishes Berssenbrugge’s ideal of the book as a physical art object. The collaged arrangement of text in the original book, of typed lines colliding with handwritten words and juxtaposed against Smith’s monoprints, embodies Berssenbrugge’s working method, her habit of cutting out texts from philosophical treatises, medical handbooks, scientific articles, and Buddhist teachings and arranging them, like a collage, with photographs and other visual materials. Appropriating the texts wholesale or altering them according to her whim, Berssenbrugge moves from work board to poem by ordering fragments, incorporating the different textures, contexts, and orders of meaning onto one surface. The result is a poetry that is alternately coherent and discontinuous, seemingly intentional in some passages and random in others. While the creation of such poems is, as Berssenbrugge has called it, an expression of freedom, the effect for the reader of being so untethered to a personal voice, to narrative, to temporal progression, or even to a poetic tradition, can be an unmoored, chaotic feeling, one that is not the same as the feeling of freedom or the form of feeling Berssenbrugge was playing out in the first place.

This reading of the poems of Berssenbrugge’s middle period is an exercise in staying attentive when every line threatens to break meaning apart. Slipping from line to line, losing track of narrative, getting lost in Berssenbrugge’s abstracting fog, one is alternately frustrated (emotionally) and rewarded (conceptually). By the time the reader arrives at “Permanent Home,” the first poem selected from Nest, this sense of exhausted patience is strangely echoed by the speaker of the first line:

I seek a permanent home, but this structure has an appearance of indifferent compoundedness and isolation, heading toward hopelessness.

Berssenbrugge has said that Nest was her first attempt to think deliberately about audience and about the responsibilities of artists, as the three poems entitled “Safety” directly consider. The voice of these poems is radically different from any of Berssenbrugge’s preceding work: intimate, simple, embodying that permanent home of a self that, while sought, is not necessarily found. “I’m so pleased to be friends with Maryanne, though I don’t understand how she has time for me, with her many friends,” begins the chatty poem “Kisses from the Moon.” Communication, community, and communion (or their failures) are the central subjects of this poem, and of the book as a whole. The same poem ends with this secret admission to the audience: “At the podium, I say in my head, ‘I love you, be my friends, exchange these promises, you to whom I aspire.’ ”

And it is on this basis that the new poems that conclude I Love Artists seem the achievement of a hard-won equilibrium, in which a personal voice (again, one that may be fictive or multiple, but which is nonetheless earnest in its desire for communication) is represented in concert with other voices. As Berssenbrugge writes in “Parallel Lines,”

It does not tear time to carry across just a single emotional line of one self in one time, like a wind that comes up.

The lines accentuate each other, land stepped with waves, grass stippled with pines, indigo threads interwoven with exquisite gold strands in the dream palace.

No longer in danger of getting lost from one line to the next, but led through lines of equally matched complexity and beauty, Berssenbrugge’s audience should be eager to follow her in whatever comes next, now that she seems truly to have revealed who she is.