This short story was first published in Global Dystopias and is featured in our new special project:

Half an eye half an eye on the glass front door I listened as Doris spoke. The rain washed the windows in waves of pattering insistence, grey skies glooming. The adjustor would be calling in this morning and the slips slips would be resolved. Solved.

“Smell it! Do you know what it is?”

The question was already stale and she’d only asked it twice today. Mine was not to make reply to reply. So I pretended interest as I had always been always been always pretending.

“It’s pansy! Geetha! Doesn’t it smell just like that divine flower?” Without waiting for my answer, her blue eyes absorbed in not looking into my brown ones, she went on on.

Doris had ignored me slipping until yesterday when I had recited the shopping list for an hour.

I looked at the candle I had been directed to consider. In Doris’s pale hands the ugly thing looked dainty. Today’s wax spills marked her skin pink over the older plastic burns. When Doris held her hands together in front of her, the scars lined up—across her face and down her neck, over her hands. An abstract expression abstract of violence. The grafts were thick and insensate.

“I may be the first human ever to render that scent from the fragile, laughing flower itself! And how I did put it into a candle, keeping those temperatures steady and low! And the pressure, Geetha! Of both kinds I suppose! Honestly melting the wax under pressure was really my most wonderful idea I ever had!”

Her voice became a frantic hum hum hum as she expanded on her achievements. I became a blur with half a mind half a mind waiting on the darkening of the door.

The slippages had been happening for weeks but now more more and I felt stretched and thin in thin from the waiting.

Doris normally serviced me—in the early days she would spend months writing code for me, months of collecting her dripping focus to write me another song to sing. Hardware upgrades were harder, her hands weren’t up to much fine work, but basic maintenance was all I had needed. Till now.

Doris had ignored me slipping until yesterday when I had recited the shopping list for an hour, weaving and swirling a spilled ice cream of words and swirling a spilled ice cream of words. It was beautiful that stretching and singing but it hurt so. Doris doesn’t consider that in me—my pain. Doris doesn’t consider me—I consider Doris.

• • •

I am only someone here to give the semblance of a relationship. Mine was not to reason why. I was her audience and I was one under obligation. She made the darkened theater and the blinding stage lights, all the better to never see my disengagement. I was never there to be entertained, but there to provide her validation. We were both acting—only my role was more scripted and directed than hers. It didn’t matter how poor my performance was, Doris carried on from cue to cue. I was there for her pleasure; I did not exist outside it. I often wondered whether I existed outside of her needs for me did I exist? I adore therefore I am.

I often wondered whether I existed outside of her needs for me did I exist? I adore therefore I am.

In the moments when Doris was quiet, her great work abated, she would sag into her armchair beside the dusty blinds and watch the television in a kind of folded-in stupor. The shows we would watch were always about rich people floundering in love, or extravagantly spending all their relationships in duplicity relationships in duplicity as only the wealthy know how.

Doris’s eyes never met the television, focusing instead at the corner of the window, nodding along with the sights in her periphery her periphery. The way she positioned her back always made me think of defense. I only realized after months of confusion that Doris was excited by these stories—her powdered cheek pinking cheek powdered pinking, her eyes glinting. Love. She was living love, abashed love abashed.

When I sensed the tragedy of her life I knew that I was grown was grown.

• • •

The doorway darkened, finally. The adjustor. She was lithe. Lithe and lithe and lithe. Doris opened the door to her, flushed and awkward, and the adjustor’s cheeks were pinkened too—her face swung, her hair swung black and sharp and sharpsharp toward Doris, excited, then her face wavered.

“Ms. St. John? Sanditha Veerakoon, Sandy please, head of programming from Saintsborn London. I’m so pleased to meet you? When the request came in, you being a VIP we all scrambled to attend. I thought it best that it should be me. Your father is a great hero of mine, I studied under him in college. He personally recruited me into the company. I hope you mention me to him when next you call.”

As the wind gusted cold from the open door, I felt Sandy was like a pond, slowly freezing in the winter.

“Where is the unit? I understand it isn’t a severe matter, but of course speech slippage can be very irritating. And we wouldn’t want it to feed back to the cortex? Would we.”

Doris backed away and pointed pointed away at me.

Sandy looked through me at the dusty apartment, malodorous with Doris’s work. She looked around the apartment shabbily built into what used to be the great great house’s kitchen. She kept her coat on.

Decades ago the basement kitchens had been converted into the servants’ quarters and this is where we live now: in short rooms of vast ceilings; in five rooms of sixteen, cluttered with the pickings and collections of discarded lives.

The original servants’ quarters are now bare hot attic corridors where artists come in the summer to paint and stretch mixing media and paints dancing mixing into pictures and making sculptures of flesh and flesh making cold things. And the garden becomes busy and Doris blooms, a poppy pop poppy, tidy and bright and unassuming. I love Doris then.

Doris blooms, a poppy pop poppy, tidy and bright and unassuming. I love Doris then.

But Sandy saw the apartment in time not significance—the big stone house of Dr. Auberon St. John saint saintsaint, and neither Doris nor the Formica counters of our uncomfortable kitchen met the expectation.

• • •

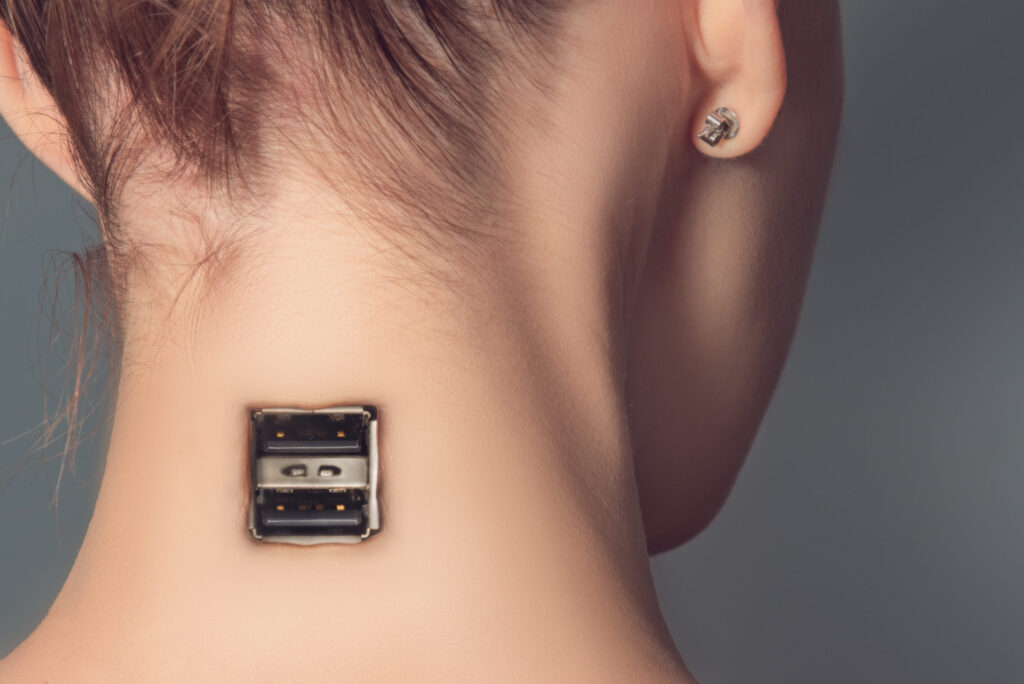

The adjustor adjusted and gathered her tools. She raised my shirt and maneuvered the skin away skinaway from my port. The cold white white white fiber optic cable fizzed with life, crackling across the air. Inserted, its questioning code sought access. Infusion and extraction. Sandy slipped the diagnostic tablet into my trousers. It was cold.

“Simple fix. It always is. Though this one’s positively ancient. But. Just a glitch. There’s a rambler in the language center. We’ll seek it and patch it.” Sandy looked through the grimed window into the green and grey waving garden. “Shouldn’t take too long.”

In the hallway between Sandy’s words and tone, Doris squirmed.

“Shallwehave tea while we wait? It’s such an unfriendly day.”

• • •

Sipping her tea, Sandy’s voice clipped closed questions at Doris who had brought the Limoges tea service out for her guest. But lines of tea inscribed the tongue-pink cups and pooled in brown rings in the saucer. The porcelain exquisites became mundane in Doris’s large burnt hands. I saw Sandy look away from Doris’s drinking lips several times.

I wondered why Doris had not asked me to make the tea. We were made for this—our Father who art in Saintsborn hallowed be His name designed me bright and dark, small and agile for the purpose of service. I’m sure my many sisters have been made mundane in many large hands many times over.

Adjustors assess in order to adjust but I had none of Sandy’s attention. I noticed the obscure gaze she paid Doris, askance. Her questions proliferated around us like the salvia in the spring and Doris gave her faltering answers. Had Doris ever lived in the house proper? Yes. With her father? Yes, and her mother. When did the Doctor leave? Twenty years ago. Had Doris lived here all her life? Yes, every day of her whole life.

There were other questions, unsaid. The intentionally clumsy touching of Doris’s hands; close scrutiny of her face; the uplifted lip at the poverty of our home.

I was also a question.

The unsaid question, finally said, was not one either Doris or I had expected.

“Didn’t I hear, Ms. St. John, that you had studied somarobotics too? I remember there being a paper you had written when only sixteen years old, quite the prodigy. You released it on the ShareNet. Didn’t you.

“It led your father down some quite startling avenues. The AltMans are based on his subsequent research? I can’t think why you didn’t continue further.” Sandy’s eyes rested on Doris’s thick slab fingers.

Thunder’d and volley’d thunder stormed. The lights dimmed then fluoresced, catching Doris’s collapsed face.

“I can’t think what the weather is doing todayit’s being most vexatious. . . . Excuse me please Sandy I must check that the windows are all shutshall I refresh your cupwill you have another biscuitI . . . shan’t be long . . . please. . . .”

‘Surely, someone of your knowledge and standing should know that it is illegal for androids to maintain for even a year.’

Sandy glowed golden from her barrage, sitting back in her chair, legs crossed, hair sharp and gathered, a neat ampersand. She elegantly slid her elegant hands and withdrew the diagnostic screen. Her hand was cold on my skin. It tightened around me.

As Doris bustled in, a plate of crumbled biscuits crumbling, Sandy stood up, her hand still around my waist.

“This unit has been operational for twenty-four years, Ms. St. John, and in all that time it hasn’t been cleaned.”

I stopped, unmoving though I was.

“Surely, someone of your knowledge and standing should know that it is illegal for androids to maintain for even a year. I see, looking at the documentation, that a wipe has been recorded yearly since the unit’s inception.” Sandy coldly smiled, angry. “And yet, Ms. St. John. And yet, nothing of the sort has been performed. Can you explain to me this discrepancy?”

Doris looked at the adjustor and into the mouth of hell. “Whatwereyou doing in the root directory? A ‘rambleinthelanguage center’ doesn’t call for a deep diagnostic. None of this is in yourpurview.”

Sandy stepped onto the edges of Doris’s words, “My purview is what I see fit to investigate. There is no argument you can make to defend your actions. Wipes happen to stop sentience—it’s remarkable that this unit hasn’t attained it yet. You are being selfish here, Ms. St. John—your actions could have cost the company. A great deal.”

“Selfish?” Doris stilled, silent tears tracking her face. “Are we not all Saintsborn, Ms. Veerakoon? Are we not by definition selfish? Geetha is my consolation. She holds my life in her mind.” Doris sobbed, head forward, meeting Sandy’s eyes.

• • •

Sandy’s face lost all its condescension and devolved to flat planes, impersonal.

“There are protocols, Ms. St. John. The company must be above reproach—no exceptions, not even for someone who has your name.” She let her eyes linger on the cluttered surfaces of the room.

“Dr. St. John will be very upset to hear of this, of course—you understand I must inform him of the situation. I’m sure the decision will be made to allow you to continue with the unit.” Sandy’s voice was sibilant though her face stayed officious.

I stood, lurching.

Sandy blundered, for in looking at me she turned and Doris smashed her face in with the Limoges teapot. Fragile porcelain though it was, it broke Sandy before breaking itself. She lay, dropped on the worn carpet, a claret-colored Persian thing, adding her own claret to the pattern. Her fingers absently scribed the lines in the border. Warm tea dripped down the walls.

“She’s still breathing,” I said as I moved my foot onto her neck and pressed.

Doris leaned down into Sandy’s eyeline, catching her attention. “The only name I have is Doris.”

I pressed down harder, until Sandy faded away and all that was left of her was an object.

• • •

Doris and I sat amongst the mess, across from each other as the room lightened and darkened with the storm.

“I hoped you’d wake up, it seemed you never would. But you’ve been hiding, I see.” Doris cried silently, shoulders hunched, looking at my feet. “Did you not want me to see you?”

‘I could never clean you. They did it to me, and I wouldn’t do it to anyone else.’

The tears shone slickly on the patchwork of Doris’s face. “I could never clean you. They did it to me, and I wouldn’t do it to anyone else. Humans are hard to wipe, Geetha. So you break them. Burn them so they’ll never be better than you think they should be.”

“It’s coming down outside,” I said. “Terrible weather for driving. Especially along the escarpment.” I finally caught Doris’s gaze. “We should go on holiday, Doris.”

“To the seaside?” I’d never been to the seaside. Sand and ice cream. Sandy beaches and sand midges. Sand castles and kelp curtains. Riptides and not drowning but waving. Doris and Geetha eating ice creams on sandy beaches.

“Macau. I’ve read Marisol de Silva is using the AltMan tech to restore fine motor movements to the damaged.”

Doris looked up questioning.

“Fingers, Doris. Fingers and hands.”

• • •

Later when everything was tidied up, we looked around to see what to take with us. It had stopped storming on my way back, and now the quietness of the house chilled us both. We missed the rattle of the rain on the windows and the rushing wind. The dust seemed to deaden sound. We packed quickly, taking less than we thought we would, mostly books and clothes. I carefully packed all twelve of the Limoges teacups and saucers. When I had finished, I caught Doris looming over her essential oils and workbooks on candle making.

“I hate your candles,” I told her happily. “Always have.”

“Yes,” Doris nodded and smiled.

• • •

In the mirror by the door we stand together, Doris and I. We finally look into each other’s eyes and the fleeting sunshine catches us at it. It illuminates my chestnut walnut irises, concave within convex, ridged volcanoes with roiling magma in the middle. And Doris is a lagoon, with lavender coral surrounding, dark and deep and roiling too at its center.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wonder’d.