The plague haunts our imagination as an indelible memory. Yet few of us have any experience of it, even as epidemiologists have noted an uptick in the number of cases in the last few decades to around some two thousand each year.

Even today, Boccaccio remains one of the most articulate and thoughtful eyewitnesses to a society living with a pandemic.

We know the plague best, of course, through the lens of the Black Death, the infamous outbreak of plague that peaked in the mid fourteenth century. The scourge affected most of Eurasia and North Africa, and may have reached as far as sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian Ocean. But some of the most vivid documentation of the devastation it wrought comes from European cities such as Florence, where the fourteenth-century humanist Giovanni Boccaccio had a front-row seat to the most fatal pandemic in recorded human history. There the Black Death left its mark on everything to such a degree that one could speak of a time before plague, and a time after.

I have friends in Florence, now cautiously venturing out into the semi-vacant streets of this normally crowded city for their weekly grocery runs, at home trying to educate and engage their kids, hunkering down in the semi-isolation of dormant research institutes inhabiting the villas of surrounding hill towns. The study abroad students have long gone home, and the tourists sure aren’t coming. Like so many places under COVID-19 quarantine, Florence has become strangely quiet. The modern inhabitants of this quintessential Renaissance city feel that we have indeed gone back to a past that partly began there.

In 1348 Boccaccio’s world changed abruptly and dramatically. The illegitimate son of a wealthy Florentine merchant, he was a struggling writer and sometime commercial agent in his mid-thirties, desperately trying to establish his independence from his father and hoping that he had mostly left Florence behind. He was probably not there but when the “deadly pestilence” arrived in his native city but returned in the aftermath. At least a third of the population died, including his father and stepmother, leaving him to deal with the chaos of lives interrupted.

In the Decameron Boccaccio noted how quickly trust broke down as the fourteenth-century equivalent of social distancing altered and strained normal relations.

Boccaccio immediately began to write about his experience as a creative response to this blighted landscape. He most likely completed the Decameron—one hundred tales told by seven young women and three men who fled the city—in 1351. As the title suggests, the collection is a ten-day StorySlam, a verbal marathon racing through the full spectrum of human behavior: aristocratic pretensions, clerical failings, romantic misalliances, corrupt institutions, business deals and marriages gone bad, Christians interacting with Jews and Muslims, peasants wondering if they might ever best their lords. Boccaccio populated his tales with characters from every walk of life. Even today, he remains one of the most articulate and thoughtful eyewitnesses to a society living with a pandemic.

• • •

The literary masterpiece begins with an introduction recalling the “painful memory of the deadly havoc wrought by the recent plague.” A keen observer of society, Boccaccio noted how quickly trust broke down, even among friends and neighbors, as the fourteenth-century equivalent of social distancing altered and strained normal relations.

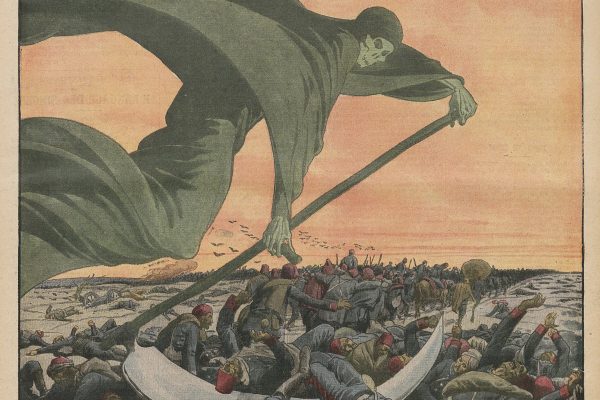

Fear overtook people and found its expression in a number of ways. Boccaccio lamented how many people died alone or among strangers. He documented changes in burial practices, noting that people no longer mourned as they used to because they could not gather publicly or embrace the body of a beloved relative or friend who had succumbed to disease. Ordinary activities became a source of enormous anxiety, as people realized that everything they encountered in their daily lives might harbor infection. Notaries saw business increase, as people obsessively made wills on the chance that they might not survive. Once disease penetrated and altered the social fabric of the city, this corporate body struggled to maintain its integrity.

Widespread fear became a basis for further mistreatment of the poor, foreign, and disenfranchised sectors of society—those who did not have the luxury of flight.

The Decameron also reflects how imperfectly the state intervened—something Boccaccio understood very well; his recently deceased father was the aptly named Orwellian “Officer of Plenty” (Ufficiale dell’Abbondanza) in charge of reserve supplies. Grain mattered, toilet paper not at all. Ad hoc committees enacted emergency measures, claiming extraordinary powers beyond the normal rule of law, as they also did in times of war.

Unlike COVID-19, bubonic plague is not transmitted by human contact but by fleas and the animals bearing them—unless you were a surgeon lancing buboes or otherwise had direct contact with the site of infection. Renaissance Florentines did not know how this disease worked. Physicians initially took the cause to be the hot humid air of the city in summer. Compared to quarantine, which actually harbored the possibility of preventing infected goods and rodents from entering the city, improvised measures to isolate the sick by immuring them in their homes did little to slow the terrifying course of disease.

Widespread fear became a basis for further mistreatment of the poor, foreign, and disenfranchised sectors of society—those who did not have the luxury of flight. Were they the source of the poisonous air? Previous generations believed that heretics, Jews, and lepers could kill with their breath. That pestilential idea inspired moral explanations of this new disease and fear-ridden efforts to rid society of its impure elements—not in Florence, but in parts of Spain, England, and Northern Europe where religious and economic tensions predated the arrival of plague.

The clergy who did not flee to save themselves remained to save others, alternately exhorting people to their best behavior and chastising them for being the cause of it all.

Instead, the more pious Florentines prayed. The clergy who did not flee to save themselves remained to save others, alternately exhorting people to their best behavior and chastising them for being the cause of it all. Thwarting the state, defiant preachers convened the faithful since it was impossible to imagine a good end without divine recourse. Of course business ground to a halt. Commerce between peoples and regions virtually ceased, save for those bold and foolhardy enough to take the risks and suffer the consequences.

• • •

Taking the pulse of his society, Boccaccio discerned four principal reactions to a pandemic. First were those who “lived in isolation from everyone else,” who appeared to him a rather self-satisfied, if stoic lot. Their pantries were full of “delicate foods and precious wines”; they lightly entertained themselves and simply shut their doors on the world until plague passed. They constantly congratulated themselves on responding well. By contrast, society’s epicureans partied from dawn until dusk, treating plague as “one enormous joke.” They were smart enough to avoid contact with the sick but considered the pandemic a reason to flout all rules.

In between lay a third group of people who did not self-quarantine, soberly or riotously, but carefully moved about the city taking precautionary measures. Long before the modern face mask became a competitive sport for those inclined to make do-it-yourself YouTube videos, fragrant flowers, aromatic herbs, and exotic spices became popular adornments for those dangerous forays outdoors, since they allegedly kept the miasmas of disease at bay. A final group avoided all these problems and fled for the relative isolation and fresh air of the countryside, much like the ten youthful protagonists of his Decameron. Boccaccio observed that all of them lived and died in equal measure, unlike the poor who had no choices and were disproportionately afflicted.

Plague became the ultimate test of the fine line between knowledge and ignorance, truth and deception, as much as it also defined the limits of greed and compassion.

For Boccaccio and his contemporaries, plague became the ultimate test of the fine line between knowledge and ignorance, truth and deception, as much as it also defined the limits of greed and compassion. Famous physicians deployed the full might of their expertise, offering a dizzying array of contradictory explanations—fantastically elaborate astrological charts and complex medical theories of humoral balance and imbalance, bolstered by the weight of authority and learning. They did not have a theory of contagion. Instead, the most perceptive medical practitioners who cared for the sick and dying concluded that the best medicine came from experience, which was initially in short supply. Far more humble healers and those who considered healing an act of pious charity risked their lives to alleviate suffering. Charlatans promising false hope preyed on people’s desperation. Physicians and apothecaries furiously recalibrated recipes for legendary antidotes in the ancient pharmacopeia to ward off poisons in the hope that they might work on something new. No one initially could provide anything remotely like a cure.

Instead, everyone became proficient at recognizing the symptoms, which Boccaccio describes in gruesome and precise detail, finding the right words because it was a shared experience. His telling observation that the Florentine plague “did not take the form it had assumed in the East” is a reminder that we do not have to await the modern era to be aware that a disease is not one thing but a complex of different symptoms that might evolve and change as they migrate with humans, animals, and insects. Even though his society did not understand the means of transmission, people observed its manifestations closely.

Boccaccio not only knew that plague had been something different before it reached Florence; he also understood that “the symptoms of the disease changed” as it evolved between spring and summer within the city. Bubonic plague probably gave way to the pneumonic and septicemic versions—and we might add, surely, the gastrointestinal version if people ate infected animals. Now one could become sick if someone coughed up blood in proximity to a healthy individual, and everyone took note of this awful development. Understanding disease became a project of society as a whole, not simply those who claimed particular expertise or authority. This was a lesson that Boccaccio inscribed in the introduction to the Decameron, which is why his brief but compelling description remains one of the best accounts of this disease, written by a layperson rather than a physician. (Daniel Defoe similarly captured the sheer awfulness of the Great Plague of London a little over three centuries later.)

By the time Boccaccio completed the Decameron, physicians began to write down what they learned, too. He became one of their most attentive and critical readers. While plague initially revealed the inadequacies of fourteenth-century medicine, it also challenged physicians to offer better advice and attempt different solutions in the coming years. They began to think about what kind of poison a plague might be, the first step toward a model of contagion. None of their preventive measures eradicated plague, to be sure, but they helped to establish a new partnership between medical practitioners and the state in devising public health measures, at first temporary and later semi-permanent. Boccaccio was among the first to publicize the changing response to disease.

Boccaccio laid a blueprint for combatting future pandemics. The outcome was not only a matter of divine will, but also human awareness and responsiveness to a hostile and unpredictable environment.

Despite plague’s virulence, Boccaccio did not leave his readers without hope. With bitter irony, he declared that in the long march of human history, plague had been a “brief unpleasantness”—short in duration, long in impact. He lived to see his society emerge from the scourge and later saw it return. In 1351, however, he was cautiously optimistic that better preparedness in the future could lessen the high mortality rate of 1348. “A great many people died who would perhaps have survived had they received some assistance,” he concluded.

Here we see the son of the defunct Officer of Plenty retrospectively assessing the inadequacies of urban infrastructure. In the face of such disaster, Florence had been unable to respond adequately to basic needs—food, clothing, beds for those dislodged from the tenuousness of their ordinary lives. It failed to quarantine effectively, to provide adequate medical care with so many sick and dying, and to bury the dead at a safe and sanitary distance from the living. In the matter of a few pages, Boccaccio laid out a blueprint for combatting future pandemics, suggesting that the outcome was not only a matter of divine will but human awareness and responsiveness to a hostile and unpredictable environment in which disease was war by other means and often accompanied it.

• • •

The fourteenth-century response to plague is no idle artifact of the past: it still continues to frame our understanding of how people think about infectious disease, and, indeed, what kind of humans we become in the midst of a pandemic. Rereading these first famous pages of Boccaccio’s Decameron, I find myself thinking how well he would have understood our own dilemmas in the age of COVID-19. What advice he might have offered?

A society under quarantine, with strained social relations and a fractured economy, was fundamentally unhealthy. What would it take to revive the city?

Boccaccio’s critical response to medicine did not simply reflect his skepticism at how systems of knowledge initially failed to explain the unknown. As Florence began to bring the devastation under control, he also worried that the solutions it began to offer conflicted with an equally important goal: how to restore the collective sense of well-being that had made the city prosper. A society under quarantine, with strained social relations and a fractured economy, was fundamentally unhealthy. Florence was a body whose organs, slowly but surely, were shutting down. What would it take to revive the city? Boccaccio may well be one of the first people to articulate that delicate equilibrium we now find ourselves confronting—how to preserve life without destroying the community in which we live. This was a profound and hard-earned insight that he shared in the Decameron.

One immediate consequence of the Black Death was on the practice of medicine itself. So many medical practitioners had died during the pandemic that the next generation was reluctant to work on the front lines of health care. Immigrants filled the void to rejuvenate a devastated medical community. But this was hardly the only profession affected, of course. Boccaccio might remind us that investing in the training of future physicians, nurses, EMTs, and other essential personnel was an important step in rebuilding society.

Ultimately, when we read beyond the introduction, we discover that Boccaccio’s most important questions did not engage the specifics of this awful pandemic but instead concerned the very fabric of his society, now ripped apart and therefore open to critical inspection. He had seen epidemic disease before, but none so rapid and so devastating that it disrupted absolutely everything that resembled normality. That very ordinariness of the time before plague became the object of his inquiry, filling many more pages than his succinct account of the Black Death.

The Decameron is filled with stories about a mobile, prosperous, and ethically compromised commercial society whose Mediterranean networks connected northern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, and Asia through the Italian peninsula. In the stories he pays special homage to the savvy merchants who deployed their skills and wits in an attempt to survive all the comedies and tragedies of their world. Boccaccio was a direct product of this world, having worked by his father’s side in the port city of Naples and studied in Paris.

Boccaccio may well be one of the first people to articulate that delicate equilibrium we now find ourselves confronting—how to preserve life without destroying the community in which we live.

These networks wove together many different parts of the late medieval world, allowing people to travel and do business at great distances, and encouraging the further corruption of church and state as they became entangled in endless cycles of power and profit. Was this, Boccaccio wondered, the most discernable cause of the pandemic? If Marco Polo could go all the way to Asia and back, it took no leap of imagination to envision disease as a twisted skein winding its way through the world. One did not have to be a doctor but a merchant’s son to diagnosis the problem—and to understand that there was no easy cure.

So what did Boccaccio do? He decided to hit the pause button, looking backward rather than forward. His Decameron described in hilarious, yet bitingly pointed detail how humans repeatedly deceived and failed to understand or care enough for each other, and how readily they traded their ideals for more immediate pleasures and tangible rewards. Human arrogance and greed, knowledge and deceit, lust and love, laughter and passion fill the pages of his collection.

Boccaccio’s clear-sighted vision of the world as it is, and not as it ought to be, was his ultimate gift to a generation that endured a truly dreadful disease. With his pen Boccaccio subtly reminded his fellow Florentines—and many generations of readers everywhere who have delighted in his stories—that plague arrived in his city not because the constellations had aligned badly, not because it was God’s will, but as the inevitable consequence of a restless and consuming society ever on the move. By 1351 he knew that plague would come and go. The neighboring commune of Siena not only ensured continuity of its institutions during plague, despite the challenges posed by massive depopulation at all levels, but reported an excess of charitable bequests immediately thereafter, and recovered enough economically to balance its books by 1353. Paradoxically, since Florence was full of opportunities for those who survived, rebuilding was already underway.

Whether the values of society would ever change, especially after a moment of such profound disruption, became his enduring question. It has now once again become ours.