Three Californias: The Wild Shore, The Gold Coast, and Pacific Edge

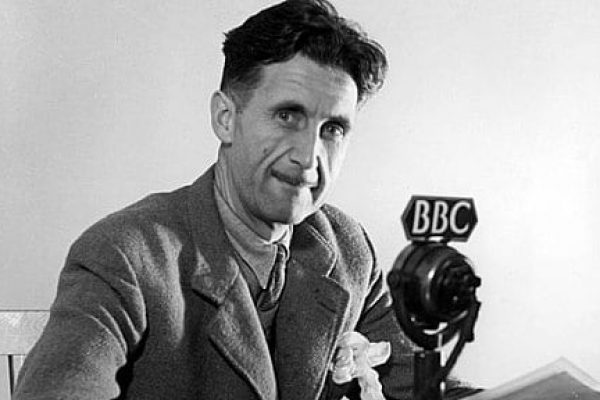

Kim Stanley Robinson

Tor Books, $27.99 (paper)

“The daily blitzkrieg of the news,” bemoans Tom Barnard in leftist science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson’s 1990 novel, Pacific Edge. “Every day everything a little worse.”

The year is 2012. The planet is warming; species are going extinct. Wars plague the globe, economic depression only further immiserates the poor, far-right parties are seizing on anti-refugee sentiment to win elections in Europe. A pandemic pours fuel on the fire of xenophobic policies, while justifying government crackdowns on activists. It feels, Tom writes, like the end of the world.

This fictional portrait of 2012 also feels, to the contemporary reader, like real life in 2020. So it’s a bit of a magic trick that, in the same novel, Robinson makes you believe in utopia.

Taken together, Robinson’s trilogy forms a meditation on how we relate to the past, and how these relationships can and can’t guide us to a brighter future.

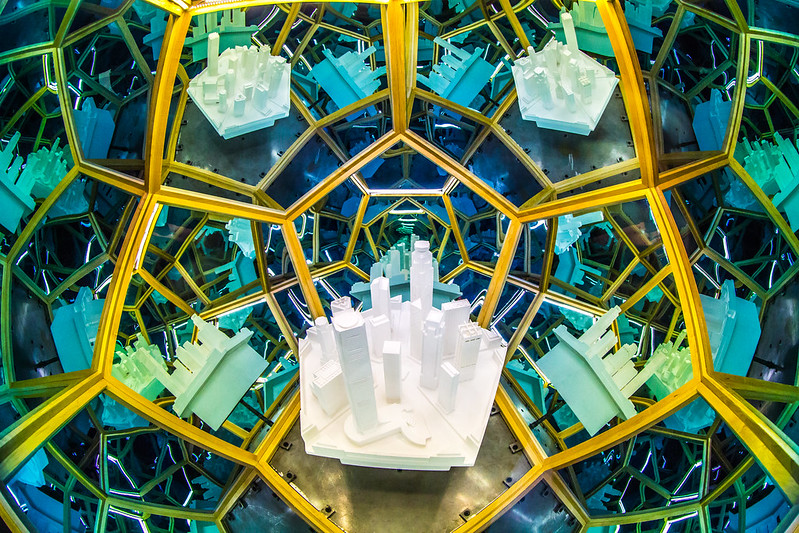

Pacific Edge is the third and final novel in a series Robinson composed throughout the 1980s, one of the earlier books in the author’s now nineteen-novel oeuvre. Re-released by Tor Books this year in a one-volume, 930-page edition, the Three Californias trilogy imagines three possible futures for the world writ large through the lens of Orange County, California. The first two novels offer variations on barbarism; in the last, Robinson gives the first of what will be several stabs throughout his career at utopia.

All three books are a pleasure to read, though the prose is less consistent than in his later Mars trilogy. Most striking, perhaps, are the moments of real prescience: each book foresees some crucial aspect of America under Donald Trump and offers, if not prescriptions, helpful tools with which to examine our present. The novels also hold up as thorough and plausible outlines of the potential futures we have ahead of us, made only more realistic by the passage of time.

The series begins with The Wild Shore (1984), in which a nuclear attack has decimated the United States, knocking technology and economies back hundreds of years. Many throughout the country dream of restoring America to what they imagine is its former glory—a glory whose warts they never saw up close. Next, in The Gold Coast (1988), we see Robinson’s portrait of an America where that “glory” has run amok: a hyper-capitalist society that, rather than fetishize the past, barrels ever onward in the name of progress, with nary a thought given to the land or the global poor. Here, Robinson’s focus is on a disillusioned young man struggling to figure out how to resist.

Finally, in Pacific Edge (1990), a series of flashbacks to 2012 shows a world falling apart, even while the bulk of the novel focuses on how that world might look should it be put back together. The nuts and bolts of this future green society—how they arrange transit, housing, jobs, construction—offer genuine guidance to the contemporary left, worth mining for ideas as we envision and fight for a Green New Deal. The novel’s political debates, in particular those between wildlife preservationists and human-oriented developers, are the sort that won’t go away even after capitalism and that demand attention by today’s advocates of environmental justice. (In fact, similar debates are already raging between, say, solar companies and desert conservationists.)

All together, the trilogy forms a meditation on how we relate to the past, and how these relationships can and can’t guide us to a brighter future. It also raises the enduring question of American greatness, asking, in particular, whether anything in it might be redeemed.

I. Making Orange County Great Again

The Wild Shore centers on several coastal California communities attempting to rebuild several decades after a sudden nuclear assault left the country unrecognizable almost overnight. In the aftermath, the United States was quarantined by the rest of the world, with the Japanese patrolling the west coast to ensure no Americans escape. More than 60 years later, in 2047, few remember life before the attack, and no one is even certain which country had carried it out.

In San Onofre, where our main characters live, farming and fishing are the main occupations, and wares not needed for subsistence are traded with other communities at swap meets. On the surface, the novel is closer to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer than to Robinson’s more political works such as New York 2140 and the Mars trilogy. The protagonist’s gee-whiz enthusiasm for life in post-apocalyptic California lends the books a fun and spirited tone that only occasionally rings false. But amid all the adventure is embedded a provocative reflection on America, and what it means for a nation to be great.

A character in Pacific Edge marvels at how people live in America. “I mean they were more prosperous than that, weren’t they? Couldn’t they have done better?” The novel asks the reader: couldn’t we?

As the series dwells so much on what we can make of the past, it is fitting that all three novels begin with an excavation. In this case, the teenaged Henry has gone with his friends to an old cemetery from before the war, when America—they have been told—was rich and powerful. For these boys the graveyard’s allure is simple: wealth. Old Tom Barnard (each book has a different version of him, a sage figure who transmits memories of the past) has told them coffins used to be “crusted with silver”. The boys, hoping to trade the precious metals at the next swap meet, begin to dig. When they find a casket, it appears their hopes are answered—solid silver handles—but on closer inspection, they realize it’s only painted plastic. The scene of disillusionment sets the tone for the book as a whole: America, it suggests, is not so precious as it first appears.

For many in the novel, the young in particular, the mythical past of the prewar United States serves both as inspiration and aspiration, a romantic ideal calling to be restored. But others are less sure: perhaps the shining silver of America’s past greatness was always just painted plastic.

To Timothy Danforth, mayor of San Diego, any such doubt is sacrilege. Henry and Tom meet Danforth when they are invited to San Diego to discuss potential cooperation between the two cities. With a firm handshake and an American flag pin in his lapel, Danforth charms Henry from the start. And at first, Danforth himself seems charmed by Tom. “Tell me, are you one who lived in the old time?” he asks. Henry thinks, “His tone seemed to say, are you one of those who used to live in Paradise?” Danforth calls Tom an “inspiration,” a “monument,” “a reminder of what we’re striving for.” And what is that, Tom wonders?

The San Diegans, we learn, are part of a burgeoning “American resistance,” loosely connected with groups across the lower 48. In southern California their main task has been defense; the Japanese are facilitating secret tourist visits for foreigners. Danforth’s men are organizing raids against these visits, killing the tourists and their guides. Tom is skeptical of this tactic, but Danforth sees it as essential. Written in the first person from Henry’s perspective, the story conveys the boy’s wide-eyed excitement about the resistance and a chance to be part of it. But Tom’s wariness, and something about Danforth’s blustering demeanor—not to mention his chosen tactic of killing tourists—gives the reader pause. To a contemporary reader, the red flags really start to wave when Danforth begins waxing on his ultimate goal: “To make America great again, to make it what it was before the war, the best nation on Earth.”

Make America great again! The book was published more than three decades before Trump launched the phrase into our national lexicon, but even here it takes on ominous overtones. Danforth’s vision of an America made great is a nationalist competitive one, not just great but best. “We’ll spring out on the world again like a tiger,” he asserts. Like most Americans in the book, he resents the rest of the world for the quarantine, with racist anti-Asian sentiment particularly widespread.

To Danforth, greatness restored means “another Pax Americana, cars and airplanes, rockets to the moon, telephones.” But to Tom, who actually lived it, the prospect of American greatness is more ambivalent. “America was great in the way that whales are great,” he later tells Henry.

America was huge, it was a giant. It swam through the seas eating up all the littler countries—drinking them up as it went along. We were eating up the world, boy, and that’s why the world rose up and put an end to us. . . . America was great like a whale—it was giant and majestic, but it stank and was a killer. Lots of fish died to make it so big.

Despite all his skepticism, something in Tom still misses the whale. “It was the best country in history,” he tells Henry. “That’s not saying much, but still, with all the flaws and stupidities.” Americans—at least some of them, the affluent—did have some degree of freedom, in speech, press, religion. Many had comfortable shelter, and easy access to goods and services that would have been considered luxuries throughout most of the world. It wasn’t really free, Tom concedes, and the luxury was built on the backs of the poor, the continent’s original inhabitants, the other countries gobbled up along the way.

But he doesn’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Like Langston Hughes in his 1936 poem “Let America Be America Again,” Tom recognizes that “America never was America” to many, but still clings to the dream of a truly free society, a dream America to him represented. The problem, he wants to believe, is not that some people had certain political and economic rights, but that maintaining these rights came through withholding them from others. This problem preoccupies Robinson throughout the trilogy: Is a better world for all possible, or is comfort and affluence necessarily built on the backs of others?

Tom answers the former, maintaining that for all America’s evil, it didn’t deserve to be nuked into oblivion. But he won’t join the resistance, and convinces the majority of the town to agree.

His ambivalence frustrates Henry and his friends. On the one hand, Tom’s fantastic tales leave the youth dissatisfied with the present, longing for something better than what they have—for silver casket handles, cars and radios, the theater of Shakespeare (who Tom has told them was the “greatest American”). But on the other, as Henry puts it, “We weren’t to want for the old time to come back either, because it was evil”—not silver after all, but plastic. “We didn’t have anything left that was ours,” Henry laments, “that we could be proud of. You confused us!”

To this Tom has no satisfying answer. The Wild Shore wonders whether we can really make history into a coherent narrative, or turn it into some pat morality tale. “It’s past, Henry,” says one character toward the novel’s end. “That’s all it is—the past.”

II. Welcome to the Resistance

The Gold Coast takes us to the year 2027, the belly of the whale. Its America is a global superpower, Orange County a concrete jungle of development, defense manufacturers, and highway construction. People spend much of their days on freeways clogged with self-driving cars following endless “tracks,” and green spaces are few and far between. It’s easy to imagine in our own future, a propulsive, always-busy society that puts progress above the here and now.

But Jim MacPherson, twenty-seven, stands out for romanticizing the past. Through Jim’s attempts to resist the tide of progress, Robinson explores the malaise among un- and underemployed youth that can lead to political dissatisfaction and, at times, radical action.

We begin again with a dig. Jim had heard from his great-uncle Tom Barnard that a school once existed where Fluffy Donuts Video Palace now stands. He has his friends (most of whom are just indulging him) covertly dig into the parking lot to try to find any evidence.

One problem preoccupies Robinson throughout the trilogy: Is a better world for all possible, or is comfort and affluence necessarily built on the backs of others?

Many characters in the book find Jim hard to read, but 2020 readers will recognize the type. “Jim’s depressed,” Robinson writes. He scrapes by with two part-time jobs and his parents still pay his car insurance. “His father thinks he’s a failure; his friends think he’s a fool.” Jim’s mom is more sympathetic—“There aren’t that many jobs to be had, half the kids Jim’s age are unemployed”—but his dad has little patience: “The hell they are.” He’s a frustrated poet, sick of endless wars, “the way things are” and the role his father plays in it, working as he does for a defense contractor. He’s struggling to find full-time work, vaguely socialist, wishing he were more politically involved. He more or less ghosts one “ally” (a romantic partner); another berates him, “You don’t have a real job and you don’t have a real future.” In short, he’s a downwardly mobile millennial in a community of downwardly mobile millennials.

Unfortunately, this future has no Democratic Socialists of America, Black Lives Matter, or Sunrise Movement Jim can throw his energy into, at least not that we see. He is sucked into a series of covert operations with an acquaintance, Arthur. Their first outing consists of postering a mall. “THE DEFENSE DEPT. RUNS THIS COUNTRY—RESIST,” reads one. Their next is more ambitious: sabotaging weapons factories, sneaking onto manufacturing sites and firing weapons that will eat away at plastic, reinforced carbon and other key materials. Thus Jim becomes the first Robinson character to sabotage destructive machines and infrastructure, though he’ll not be the last.

Jim talks himself into it:

His chance to make some meaning out of his life, to strike back against . . . everything. . . . He’s thinking of the evil direction his country has taken for so long, in spite of all his protests, all his votes, all his deepest beliefs. Ignoring the world’s need, profiting from is misery, fomenting fear in order to sell more arms, to take over more accounts, to own more, to make more money. . . . it really is the American way. And so there’s no choice but action, now, some real and tangible form of resistance.

Jim is no master strategist, typically acting more on feelings than reason, and we are not supposed to support or even comprehend his every decision. But it’s noteworthy that here, Robinson gives an entirely sympathetic account of his motivations. Whatever one thinks of property destruction, Robinson at least asks us to understand it. One can imagine similar rationale—striking back against a violent world—driving the eco-saboteurs of the 1980s and ’90s, or today, perhaps, a fed-up black American setting fire to a police car or making off with goods from a Nike store.

But this comparison also shines a light on some of Jim’s own shortcomings, and to an extent, the novel’s. While Jim genuinely desires justice for the victims of empire and capital, he acts on their behalf while making no real attempt at engaging with communities other than his own. One can understand Robinson’s choice here—that Jim is a white man with affluent parents allows him to explore what we now call privilege, and a certain breed of economic disaffection. But the reader is left wanting some picture of the agency of those most exploited.

A key consequence of Jim’s isolation is his lack of imagination. He wants revenge, motivated by longing for a past he feels is lost: species of animals wiped out, indigenous cultures destroyed, cooperative agricultural experiments failed. But, he believes, “there is no way back. History is a one-way street. It’s only forward, into catastrophe, or the track-and-mall inferno, or . . . or nothing. Nothing Jim can imagine, anyway.” If there’s no path forward, then nothing to do but blow up the current system. He has a passing dream of some “cataclysm that could bring this overlit America to ruin,” leaving behind a small group of survivors who might be able to live less alienated lives. (That is, he envisions the previous book.)

By contrast, today’s anti-racist movement advances a forward-looking vision in which the alternative to state violence is rooted in community. Imagination plays a key role in movement rhetoric; writers, artists, and organizers ask us to envision a world without police, to dream of what we could create with increased funding for education, health, housing. In Minneapolis, activists commandeered a hotel in late May to shelter the city’s homeless. Even so-called looters often distribute everything from televisions to tampons among their neighbors, deepening community ties. While the movement draws on ideas and examples from its history, the goal is something new rather than a return to some romanticized past.

In the book, it’s Arthur who provides a counterweight to Jim’s nihilism. Despite his radical tactics, his politics are fairly tame: he’s more or less a Bernie Sanders–style social democrat. “It’s not that radical a vision,” Arthur concedes, and imagines it can be won by vote rather than by violence. (Indeed, this happens in Pacific Edge.) But that evolution needs a push: “I’m convinced that unless the plan includes active, physical resistance, it isn’t going to work.”

Utopias are no substitute for other forms of political action, but they can help orient us toward what we are trying to build.

Jim senses that destruction can’t be enough on its own: a desire to imagine and experience alternative ways of life takes him and his friends on a continent-hopping vacation, trying to find some foreign culture or ancient monument that feels genuinely distinct, that retains character and personality amid the onslaught of global capitalism. They have little luck. Behind the Iron Curtain, they are exasperated to find that the roads and sprawl of St. Petersburg look basically like Orange County. They go to the pyramids in Giza, and find them to be just another tourist attraction. “Kind of like the Matterhorn at Disneyland,” says Jim’s friend Humphrey.

They do finally find an abandoned ruin on Crete, delighting in some corner of authentic land left (even if the culture that once inhabited it is dead). But the real alternative world Jim finds on the trip is not on an island, but in a neighborhood of beggars in Egypt. “This man, this woman, this infant,” he thinks. “This is the world. This is the real world.”

As in The Wild Shore, Robinson is concerned with global inequality, and the economic privilege of upper-middle class Americans. In the earlier novel, he explored a world in which those Americans get their comeuppance, destroyed and quarantined by a world that grew tired of oppression. In this novel, the global affluent have continued their power drive with no real consequences, other than the estrangement of their children.

Returning to Orange County, Jim wonders, “How many people could live in a structure like [South Coast Plaza mall]? The luxury surrounding him, he thinks, is a deliberate, bald-faced denial of the reality of the world. A group hallucination shared by everyone in America.” (“Everyone in America,” of course, is itself a denial of the slums existing in Orange County, where his churchgoing mother volunteers.) In the face of such injustice, he struggles to make sense of his own life, understanding it as delusion. “In a world where the majority of all the people born will starve or be killed in wars, after living degraded lives in cardboard shacks . . . do his middle-class suburban Orange County memories matter at all? Should they matter?”

Again, the book’s resolution is inconclusive. Attempts at an answer are withheld until the third novel.

III. Out of Barbarism

In Pacific Edge Robinson at last tries his hand at utopia. Kevin, our protagonist, is a recently elected Green to El Modena City Council. Everyone bikes everywhere, with no privately owned cars; corporations have a maximum size, and their executives have a maximum income (the top earners are now “hundreds” rather than “millionaires”). None want for food and shelter, and all receive a basic income. It is not a perfect utopia—still wracked by fires and typhoons, for instance, in an ecologically destabilized world—but one where capitalism has been transcended and democratic communities worldwide, perhaps especially in nature-loving California, are beginning to heal the rift between human and nonhuman nature.

The excavation at the opening sets up a radically different approach to the past than in the previous books. As part of collective town work (everyone must put in ten hours a week), Kevin and his friends are digging up materials from an old traffic intersection to be repurposed. All are faintly disgusted at the era’s decadence—multiple sets of traffic lights on the same pole? They debate whether this was a failure of values, or simply an inevitable symptom of affluence.

What’s lacking is any of Hank or Jim’s reverence for the past: here, capitalist society is an embarrassing relic, the world must be dismantled and remade. But the tack is also different than Jim’s blow-it-all-up strategy. As Kevin articulates his Green politics: “Renovate that sleazy old condo of a world!” This is, in fact, Kevin’s day job. He’s an architect, transforming tract houses and McMansions into energy-efficient, food-producing, communal living spaces. This is more or less the project of his whole society.

The novel’s central conflict, on the surface, involves the complexities of water rights and zoning law. More fundamentally, however, it’s about questions that have begun to plague today’s climate movement, around values, economic growth, and connection to the land. It’s also a meta-commentary on the very nature of utopia. In a series of flashbacks (all italicized), we read the diary entries of this book’s Tom Barnard (Kevin’s grandfather), who, like the real Robinson, is working on a novel. “Writing a utopia,” he muses. “Certainly it’s a kind of compensation, a stab at succeeding where my real work has failed. Or at least an attempt to clarify my beliefs, my desires.” This Barnard, we learn, had been a public defender, worked for an environmental organization and a socialist party, and come to the conclusion that “nothing I did there would ever change things.”

Whether the young Tom believes in a better society is an open question. Throughout the novel he struggles with whether his book is useful or a waste of time. He worries utopias are “a cheat,” declaring it worthless to imagine a paradise disconnected from the rest of the world. “There’s no such thing as a pocket utopia,” he insists. The French aristocracy, he thinks, probably thought they lived in utopia—but in fact they were “parasites, brutal, stupid, tyrannical,” and the underclass got its revenge. So it must be, he thinks, for the bourgeois affluent of the Global North, himself included.

His ambivalence sets the context for what the rest of the book—set 53 years later, in 2065—is trying to do:

Must redefine utopia. It isn’t the perfect end-product of our wishes, define it so and it deserves the scorn of those who sneer when they hear the word. No. Utopia is the process of making a better world, the name for one path history can take, a dynamic, tumultuous, agonizing process, with no end. Struggle forever.

For Kevin, our thirty-two-year-old architect, the struggle continues. Alfredo—the mayor, a “hundred,” and a member of the Greens’ opposition party—intends to propose a development on Rattlesnake Hill behind Kevin’s house, the last untamed patch of land within city limits and a favorite spot of Kevin’s. What’s more, the development would include a new office space for Alfredo’s medical equipment company.

Yet Alfredo is no cartoon villain seeking only personal enrichment. He points out that more industry means a higher “town share”—the localized basic income—and thus greater prosperity for all; his company also manufactures genuinely life-saving medical equipment. The Greens had controlled the council for a long time, and the economy had undergone a sustained period of planned contraction, leading to greater equality and more ecologically mindful practices. But, Alfredo argues, we can’t just keep shrinking forever.

These debates evoke contemporary conversations in the climate and environmental movements. Many advocate “degrowth,” reining in the materials and energy used by human society and thus reducing economic activity. But critics worry this would mean forcing people to live in relative poverty.

For their part, Kevin and company are degrowthers through and through. In El Modena (unlike on the contemporary left), the Greens focus heavily on the value they place upon nonhuman nature. Kevin feels a keen connection to place. There are no appeals to “ecosystem services,” or the economic value of wild habitat, but merely a plea to recognize and appreciate the land’s intrinsic worth. Those in real life sympathetic to degrowth, in my experience, tend to share a similar outlook—ecologically minded, seeing themselves as embedded within nature rather than masters over it. Like Kevin and his friends, they look at all this society’s consumption and stuff with disdain. Their sensibilities lean toward imagined futures filled with green spaces, wildlife, a slower pace.

The nuts and bolts of the future green society Pacific Edge imagines—how to arrange transit, housing, jobs, construction—offer genuine guidance to the contemporary left, worth mining for ideas as we envision and fight for a Green New Deal.

Those who prefer to see a world of greater material abundance are rarely moved by these appeals. They also hope we work less, but don’t want to slow down the machines, typically more excited by the potential for new human achievement and technology—including through large-scale projects like geoengineering or asteroid mining—than the preservation of nonhuman life for its own sake. Alfredo may not be a “luxury communist,” but his company—fast-growing, producing impressive and life-saving technology—is exactly the sort prized by that value system. What is the paving of one more hill compared to human well-being? Kevin, of course, is obstinate: not this hill. If you want to put growth first, he tells Alfredo, move out of El Modena.

Robinson himself appears sympathetic, but one of his cleverer tricks is to make his future world heterogeneous. El Modena is not a pocket utopia—the economic reforms are global—but it is, we realize, an unusually green-minded town. This becomes clear through the commentary of the Chicago lawyer Oscar, who thinks they “bike to excess” and is horrified to learn a “garden party” involves actually gardening. “Arcadia! Bucolica! Marx’s ‘idiciocy of rural life’! It all really exists!” he writes to a friend in Chicago. And even in nearby Irvine (where Kevin tells Alfredo to move to), housing styles are radically different: neighborhoods look “like a museum exhibit or an architect’s model, or like Disneyland,” Tom complains. “It’s nostalgia, denial, pretentiousness, I’m not sure which. Live in a bubble and pretend it’s 1960!” Such localized, place-based communities might feed blood-and-soil environmentalism, or at the very least insularity. But still lawyers and scientists visit El Modena from far and wide, insuring cultural interchange, and each household video chats monthly with “sister families” around the world.

It’s a subtle rebuke against the anti-Asian nationalism of The Wild Shore and America’s hegemony in The Gold Coast. Indeed, Kevin’s friends are not only geographically diverse but represent a wider range of races, genders, and ages than the main characters in the other novels; in another departure from the previous books, women occupy more prominent political and professional roles. These issues are rarely in the foreground, and the trilogy as a whole could have benefited with more direct and less clumsy engagement with race in particular. But it’s also clear Robinson understands segregation as part of capitalist society, and breaking down barriers as a component of liberation.

While the book never feels didactic, day-to-day life in El Modena is as good a starting point as anything I’ve read when thinking about what an actual eco-socialist society might look like: place-based yet internationalist, integrating technological innovation but encouraging less energy intensive modes of work and play. Such a vision can be genuinely galvanizing: look how the promise of a Green New Deal, along with videos and articles imagining what that GND might look like, helped energize the climate movement. Or again, look at the visions of community investment and care central to anti-racist, anti-police organizing. While the presumptive Democratic nominee wants to take us back to how things were before, the left is finding its spark in forward thinking.

In the book, Tom Barnard gives up on his utopian novel to focus on enacting actual change, going to work for a new political party. Like Jim before him, Tom is forced to confront his privilege among the global affluent:

While I was growing up in my sunny seaside home much of the world was in misery, hungry, sick, living in cardboard shacks, killed by soldiers or their own police. . . . Everyone should get to know [utopia], not in the particulars, of course, but in the general outline, in the blessing of a happy childhood, in the lifelong sense of security and health. . . . They will look back and judge us, as aristocrats’ refuge or emerging utopia, and I want utopia.

Here is something firmer than we get in the previous books: a commitment to take what is good in America and make it universal rather than exclusive, while ruthlessly discarding the rest.

Robinson, unlike Tom, is still writing utopias. His next novel, due out in October, seeks to imagine the best-case scenario for the next thirty years given where we are on climate change and mass extinction. This makes it probably “one of the blackest utopias ever written,” he told Newsweek.

Utopias are no substitute for other forms of political action, but they can help orient us toward what we are trying to build. Kevin’s favorite part of his construction job is “changing bad to good,” he says, and in way that’s the alchemy Robinson tries to pull off in his books. “Man, I go into some of those old condo complexes, and my God,” says Kevin. “Little white prison cells, I can’t believe people lived like that! I mean they were more prosperous than that, weren’t they? Couldn’t they have done better?”

Pacific Edge asks the reader: couldn’t we?